You might assume Orange County law enforcement would be at the peak of professional diligence as it handled the kidnapping and murder of Jeanette Espeleta, a 20-year-old Fullerton woman eight months’ pregnant with a baby she planned to name Alyssa Kaitana. But the July 1998 double homicide has evolved into an ongoing showcase of incompetence and corruption involving police, sheriff’s deputies, county counsel, prosecutors and a seasoned judge.

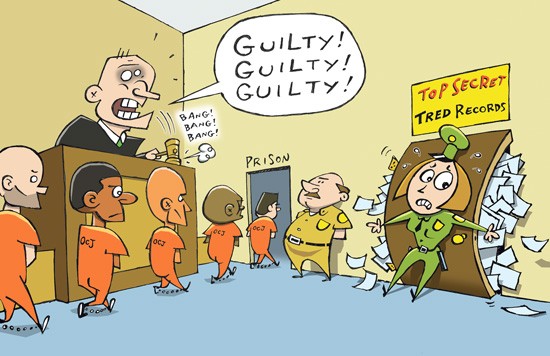

Such a story would have been difficult for the public to accept not long ago. But last month, OC District Attorney Tony Rackauckas’ death-penalty prosecution team got caught committing perjury and hiding crucial records, unprecedented findings that prompted Judge Thomas M. Goethals to recuse the entire district attorney’s office in People v. Scott Dekraai, the 2011 Seal Beach salon mass killer.

Similar to Dekraai, government actors took the easily solvable Espeleta murder and unnecessarily cheated. In some ways, the Espeleta case is worse than the lingering aforementioned death-penalty trial that has garnered national attention. During the past 17 years, prosecution teams hid exculpatory evidence, secured tainted testimony, won convictions, and then duped state appellate-court justices into believing they never swerved from their sworn oaths. It’s an alarming situation that’s not based on speculation. While most prosecutors and cops I see in court are honest, some even significantly underpaid for their work, the record alone in the Espeleta mess proves OC’s criminal-justice system needs a cleansing.

If you doubt my observation, contemplate this: In recent months, we’ve learned, over the objections of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department (OCSD), that the agency created TRED, a computerized records system in which deputies store information about in-custody defendants, including informants. Some of the data is trivial; other pieces contain vital, exculpatory evidence. But for a quarter of a century, OCSD management deemed TRED beyond the reach of any outside authority. In Dekraai, deputies Ben Garcia and Seth Tunstall committed perjury to hide the mere existence of TRED. Those lies didn’t originate from blind loyalty, however. The concealed records show how prosecution teams slyly trampled the constitutional rights of defendants by employing informants–and then keeping clueless judges, juries and defense lawyers.

This scam returns us to Espeleta. Twenty-two days before her death, the victim filed paperwork with the OC district attorney’s office seeking future child support from the unborn baby’s father, Richard Tovar. Fullerton Police Department (FPD) investigators focused on Tovar, determined he was the killer and won a conviction. Officers also pursued murder charges against 20-year-old Henry Rodriguez, Tovar’s best friend. Rodriguez was at Anaheim Stadium during the killing and had considered Tovar’s pre-murder “187” rants against Espeleta as empty talk fueled by dope. Detectives Tom Conklin and Robert Richardson got Rodriguez to admit he’d heard Tovar’s rants and, after the murder, helped him dump the corpse in the Pacific Ocean. In 1999, a jury convicted him on first- and second-degree murder counts.

Though Rodriguez landed in prison, the case was only on the first wave of a wild roller-coaster ride. A California Court of Appeal panel with justices William Rylaarsdam, David Sills and Kathleen O’Leary overturned the convictions in 2003, declaring Conklin and Richardson ignored the law to coerce a partial confession, in violation of the defendant’s Miranda rights. “The transcripts and videotapes of the interview show the detectives were intent on extracting every last detail possible from the defendant before formally placing him under arrest and informing him of his constitutional rights; they succeeded,” the judges wrote.

The second trial put the Rodriguez prosecution team in a quandary. This time, they couldn’t use the illegally obtained confession, so they unveiled a startling new weapon: Michael James Garrity, an Orange County Jail informant. Garrity claimed he’d secured much of the same incriminating information from the defendant prior to the first trial. But the tardy emergence of a snitch raised a question: Why had Garrity been hidden?

The answer is contained in the snitch’s notes and police interviews, which reveal unethical acts.

[

Federal law in Massiah v. United States establishes that government agents and their informants cannot question charged defendants who have legal representation. But Garrity’s long-hidden, June 7, 1999, recorded meeting with FPD detectives Sean Fares and Anthony Sosnowski is loaded with the informant admitting he’d repeatedly asked questions. For example, he uttered statements such as “I asked [Rodriquez] how they shot [Espeleta]” and “I asked how she was killed.”

Worse, according to the transcript, Fares and Sosnowski ignored the Massiah violations and brazenly provided Garrity a wish list of questions they wanted asked. “A couple of things we’re gonna want to know, if you, if you can, uh, solicit from him, um, is: Where is the [victim’s] car?” said Sosnowski, now a supervising investigator for Rackauckas. “Maybe you can get him to tell you that somehow.”

That evidence troubled James M. Crawford. As Rodriguez’s attorney for the second trial, Crawford viewed the state’s cases as warped from the outset. “Henry didn’t murder anyone,” he said. “He helped dispose of the body.”

At a March 25, 2005, hearing with Judge Frank F. Fasel, Crawford asked to inspect “relevant impeachment” information: sheriff’s records on Garrity’s informant work. Laura Knapp, a deputy county counsel representing OCSD, objected. Knapp argued, “It is the sheriff’s contention that these records are highly confidential, investigatory files, which are not written or created [my emphasis] and should not be disclosed.”

Labeling Crawford’s keen insight “a fishing expedition,” Fasel accepted Knapp’s perplexing stance (supposedly nonexistent records are confidential), declared that Garrity had not been acting as a government informant when he questioned Rodriguez, permitted the snitch’s testimony, oversaw the defendant’s second trial conviction and imposed a sentence of 40 years to life.

None of this bothered appellate justices Rylaarsdam, Sills and O’Leary. Garrity clearly noted during his FPD interview that he’d questioned Rodriguez in violation of Massiah, but the panel claimed there was “no evidence of a deliberate elicitation of the information.” To help reach that conclusion, the justices simply echoed law enforcement’s fiction: Not working as a government snitch, Garrity stumbled upon the incriminating Rodriguez statements, a scenario that permitted the introduction of that evidence.

But as with Crawford, as well as Rodriguez’s first trial defense lawyers, the justices hadn’t just been misled about the existence of an OCSD informant program. All were robbed of vital, contradictory evidence. TRED entries contain information the defense was entitled to know, including that Garrity worked as an informant before, during and after his questioning of Rodriguez.

The TRED records aren’t ambiguous. Before going operational against Rodriguez, the snitch ratted on other inmates possessing methamphetamine, performed informant work for Riverside authorities, worked to aid OCSD deputies on “several matters,” and solicited information from multiple murder defendants on behalf of Anaheim and Fullerton police. In an April 1999 TRED entry, a deputy wrote, “[Garrity] is very cooperative and has apparently provided staff with good information.”

The TRED revelations, 17 years late in this case, demonstrate the government can’t be trusted to obey court rules to surrender evidence helpful to the defense and could prompt a third trial for Rodriguez.

“This is a due-process disaster zone,” said Scott Sanders, the assistant public defender who forced disclosure of the TRED system late last year. “The sheriff’s department created a records system in 1990 and has pretended it is immune from court disclosure. How many more convicted defendants were cheated during the past 25 years?”

Follow OC Weekly on Twitter @ocweekly or on Facebook!

CNN-featured investigative reporter R. Scott Moxley has won Journalist of the Year honors at the Los Angeles Press Club; been named Distinguished Journalist of the Year by the LA Society of Professional Journalists; obtained one of the last exclusive prison interviews with Charles Manson disciple Susan Atkins; won inclusion in Jeffrey Toobin’s The Best American Crime Reporting for his coverage of a white supremacist’s senseless murder of a beloved Vietnamese refugee; launched multi-year probes that resulted in the FBI arrests and convictions of the top three ranking members of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department; and gained praise from New York Times Magazine writers for his “herculean job” exposing entrenched Southern California law enforcement corruption.