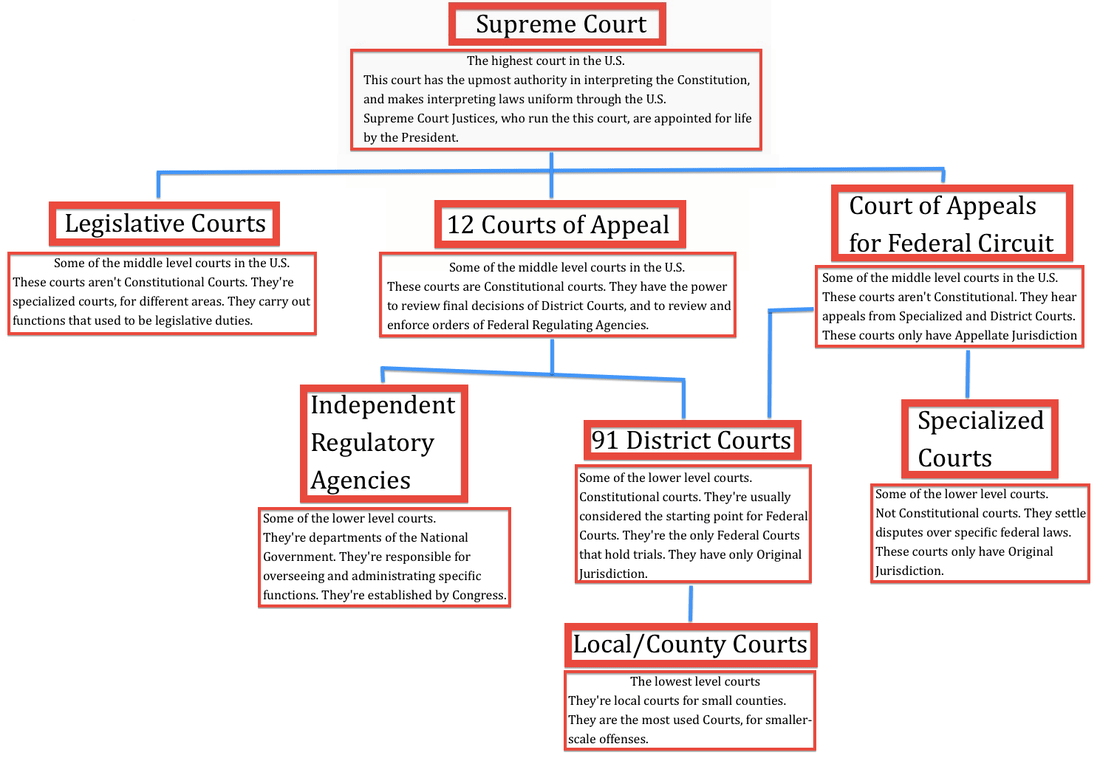

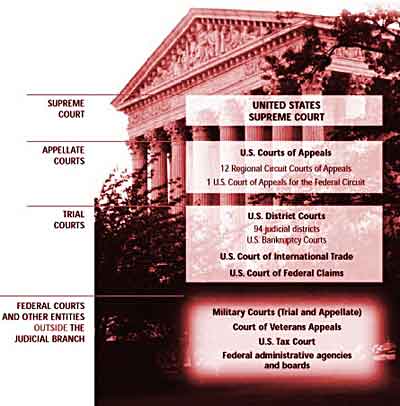

Court Role and Structure – Hierarchy Structure of the US Courts

Federal courts hear cases involving the constitutionality of a law, cases involving the laws and treaties of the U.S. ambassadors and public ministers, disputes between two or more states, admiralty law, also known as maritime law, and bankruptcy cases.

The federal judiciary operates separately from the executive and legislative branches, but often works with them as the Constitution requires. Federal laws are passed by Congress and signed by the President. The judicial branch decides the constitutionality of federal laws and resolves other disputes about federal laws. However, judges depend on our government’s executive branch to enforce court decisions.

Courts decide what really happened and what should be done about it. They decide whether a person committed a crime and what the punishment should be. They also provide a peaceful way to decide private disputes that people can’t resolve themselves. Depending on the dispute or crime, some cases end up in the federal courts and some end up in state courts. Learn more about the different types of federal courts.

Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is the highest court in the United States. Article III of the U.S. Constitution created the Supreme Court and authorized Congress to pass laws establishing a system of lower courts. In the federal court system’s present form, 94 district level trial courts and 13 courts of appeals sit below the Supreme Court. Learn more about the Supreme Court.

Courts of Appeals

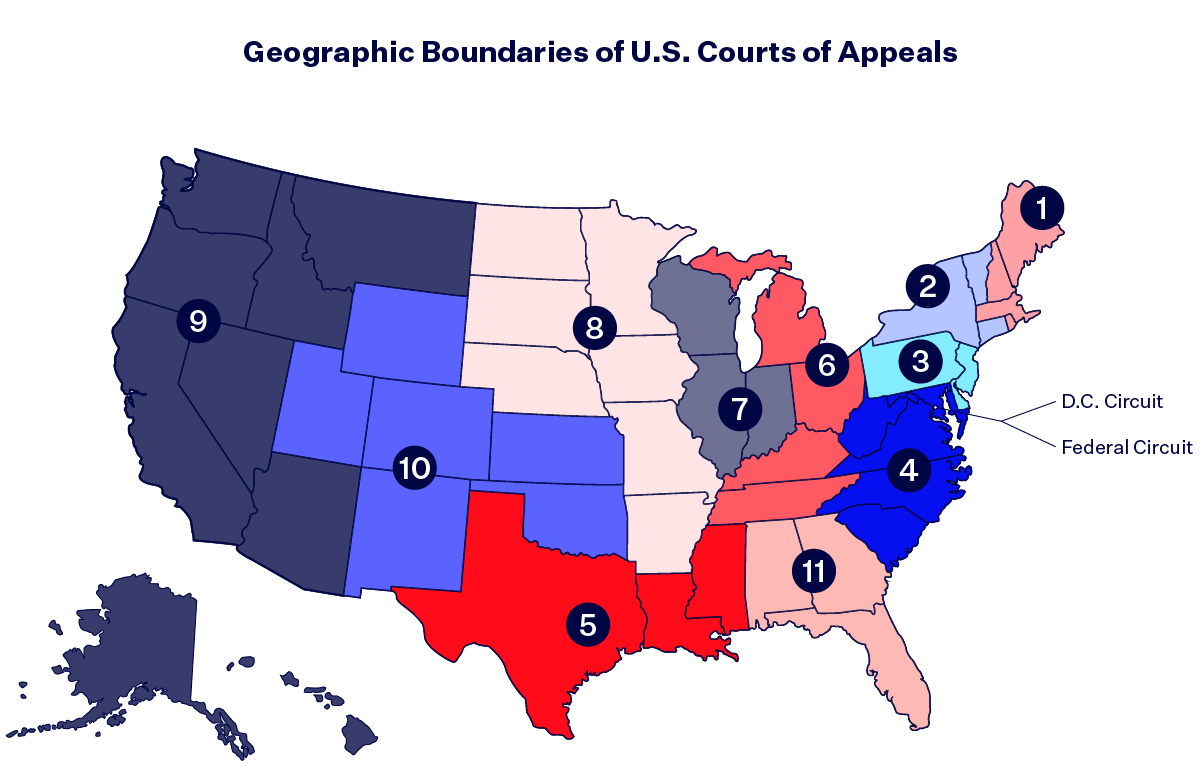

There are 13 appellate courts that sit below the U.S. Supreme Court, and they are called the U.S. Courts of Appeals. The 94 federal judicial districts are organized into 12 regional circuits, each of which has a court of appeals. The appellate court’s task is to determine whether or not the law was applied correctly in the trial court. Appeals courts consist of three judges and do not use a jury.

A court of appeals hears challenges to district court decisions from courts located within its circuit, as well as appeals from decisions of federal administrative agencies.

In addition, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has nationwide jurisdiction to hear appeals in specialized cases, such as those involving patent laws, and cases decided by the U.S. Court of International Trade and the U.S. Court of Federal Claims.

Learn more about the courts of appeals.

Bankruptcy Appellate Panels

Bankruptcy Appellate Panels (BAPs) are 3-judge panels authorized to hear appeals of bankruptcy court decisions. These panels are a unit of the federal courts of appeals, and must be established by that circuit.

Five circuits have established panels: First Circuit, Sixth Circuit, Eighth Circuit, Ninth Circuit, and Tenth Circuit.

District Courts

The nation’s 94 district or trial courts are called U.S. District Courts. District courts resolve disputes by determining the facts and applying legal principles to decide who is right.

Trial courts include the district judge who tries the case and a jury that decides the case. Magistrate judges assist district judges in preparing cases for trial. They may also conduct trials in misdemeanor cases.

There is at least one district court in each state, and the District of Columbia. Each district includes a U.S. bankruptcy court as a unit of the district court. Four territories of the United States have U.S. district courts that hear federal cases, including bankruptcy cases: Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands.

There are also two special trial courts. The Court of International Trade addresses cases involving international trade and customs laws. The U.S. Court of Federal Claims deals with most claims for money damages against the U.S. government.

Bankruptcy Courts

Federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction over bankruptcy cases involving personal, business, or farm bankruptcy. This means a bankruptcy case cannot be filed in state court. Through the bankruptcy process, individuals or businesses that can no longer pay their creditors may either seek a court-supervised liquidation of their assets, or they may reorganize their financial affairs and work out a plan to pay their debts.

Article I Courts

Congress created several Article I, or legislative courts, that do not have full judicial power. Judicial power is the authority to be the final decider in all questions of Constitutional law, all questions of federal law and to hear claims at the core of habeas corpus issues. Article I Courts are:

About California Courts

Overview

California’s court system is the largest in the nation and serves a population of more than 39 million people—about 12 percent of the total U.S. population.

The vast majority of cases in the California courts begin in one of the 58 superior, or trial, courts, which reside in each of the state’s 58 counties. With approximately 450 court buildings throughout the state, these courts hear both civil and criminal cases as well as family, probate, mental health, juvenile, and traffic cases.

The next level of judicial authority resides with the Courts of Appeal. Most cases before the Courts of Appeal involve the review of a superior court decision being contested by a party to the case. The Legislature divided the state geographically into six appellate districts.

The state Supreme Court serves as the highest court in the state and has discretion to review decisions of the Courts of Appeal in order to settle important questions of law and to resolve conflicts among the Courts of Appeal. The court also must review the appeal in any case in which a trial court has imposed a judgment of death.

California Courts at a Glance

- Court levels: 3

- Trial courts: 58—one in each county

- Court of Appeal districts: 6

- Highest court: California Supreme Court

- Judicial branch budget is 1.5% of State General Fund

California Supreme Court

- Justices: 1 Chief Justice, 6 Associate Justices

- Filings: 6522 annually

- 59 written opinions annually

Courts of Appeal

- Justices: 106 (authorized positions)

- Filings: 15,781 annually

- Dispositions: 20,159 annually

Superior Courts (trial courts)

- 1,755 judges (authorized positions)

- Filings: 4,464,380 annually

- Dispositions: 3,041,190 annually

California Judicial Branch

In California, as in the federal government, the power to govern is divided among three equal branches: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial.

The executive branch of government executes the laws enacted by the Legislature. Supreme executive power of the State of California is vested in the Governor. The Governor has authority not only to appoint positions throughout the executive branch, but also to make judicial appointments subject to the Legislature’s approval.

The legislative branch of government is the State’s law-making authority. The California State Legislature is made up of two houses: the Senate and the Assembly. There are 40 Senators and 80 Assembly members representing the people of the State of California.

The judicial branch of government![]() is charged with interpreting the laws of the State of California. It provides for the orderly settlement of disputes between parties in controversy, determines the guilt or innocence of those accused of violating laws, and protects the rights of individuals. The California court system, the nation’s largest, serves more than 39 million people with approximately 1,800 judicial officers and 18,000 court employees. The head of the judicial branch is the Chief Justice of California.

is charged with interpreting the laws of the State of California. It provides for the orderly settlement of disputes between parties in controversy, determines the guilt or innocence of those accused of violating laws, and protects the rights of individuals. The California court system, the nation’s largest, serves more than 39 million people with approximately 1,800 judicial officers and 18,000 court employees. The head of the judicial branch is the Chief Justice of California.

The Courts

- California Supreme Court

- Courts of Appeal

- Superior Courts

The Supreme Court, Courts of Appeal and Superior Courts form the core of the California Judicial Branch

Learn about the role of the various California courts as well as the administrative and programmatic committees, initiatives and other resources that support the daily operations of the Judicial Branch of California.

The California Supreme Court – The Court’s Jurisdiction

The state Constitution gives the Supreme Court the authority to review decisions of the state Courts of Appeal (Cal. Const., art. VI, § 12). This reviewing power enables the Supreme Court to decide important legal questions and to maintain uniformity in the law. The court selects specific issues for review, or it may decide all the issues in a case (Cal. Const., art. VI, § 12). The Constitution also directs the high court to review all cases in which a judgment of death has been pronounced by the trial court (Cal. Const., art. VI, § 11). Under state law, these cases are automatically appealed directly from the trial court to the Supreme Court (Pen. Code, § 1239(b)).

In addition, the Supreme Court reviews the recommendations of the Commission on Judicial Performance and the State Bar of California concerning the discipline of judges and attorneys for misconduct. The only other matters coming directly to the Supreme Court are appeals from decisions of the Public Utilities Commission.

About the Courts of Appeal

History

At the thirty-fifth session of the Legislature, on March 14, 1903, an amendment was proposed to Article VI of the California Constitution to create a more lasting solution to the continuing problem of court congestion. The amendment proposed both the dissolution of the Supreme Court Commission and the creation of three District Courts of Appeal, defining their respective jurisdictions and their composition.

The First Appellate District would be located in San Francisco; the Second Appellate District in Los Angeles; and the Third Appellate District in the State’s capital city, Sacramento. Section 25 of the proposed amendment also provided for the abolition of the Supreme Court Commission upon the expiration of its then current term. Section 4 of the proposed amendment provided that upon ratification of the amendment, the Governor would appoint nine justices, three per district, to serve until the first Monday in January of 1907.

It further provided that at the 1906 election, the justices would be elected. Each district was to have one justice serve a 4-year term, one serve an 8-year term, and one serve a 12-year term, their length of service to be determined by drawing lots. At the same time, section 17 of Article VI of the Constitution would set the annual salary of the Justices of the District Courts of Appeal at $7,000. The Constitutional amendments were submitted to the voters and adopted November 8, 1904.

Membership and Qualifications

The rules governing the selection of Supreme Court justices apply to those serving on the Courts of Appeal. Justices are appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the Commission on Judicial Appointments.

Original, Appellate Jurisdiction

Courts of Appeal have appellate jurisdiction when superior courts have original jurisdiction, and in certain other cases prescribed by statute. Like the Supreme Court, they have original jurisdiction in habeas corpus, mandamus, certiorari, and prohibition proceedings (Cal. Const., art. VI, § 10).

Cases are decided by three-judge panels. Decisions of the panels, known as opinions, are published in the California Appellate Reports if those opinions meet certain criteria for publication. In general, the opinion is published if it establishes a new rule of law, involves a legal issue of continuing public interest, criticizes existing law, or makes a significant contribution to legal literature (Cal. Const., art. VI, § 14; Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.1105(c)).

Superior Courts

California has 58 trial courts, one in each county. In trial (superior) courts, a judge and sometimes a jury hears witnesses’ testimony and other evidence and decides cases by applying the relevant law to the relevant facts. The California courts serve the state’s population of more than 39 million people.

Listing of all Superior Courts

California Judicial Branch Fact Sheet

A Visitors’ Guide to the California Superior Courts

Before June 1998, California’s trial courts consisted of superior and municipal courts, each with its own jurisdiction and number of judges fixed by the Legislature. In June 1998, California voters approved Proposition 220, a constitutional amendment that permitted the judges in each county to merge their superior and municipal courts into a “unified,” or single, superior court. As of February 2001, all of California’s 58 counties have voted to unify their trial courts. Learn More.

The U.S. Court System Explained

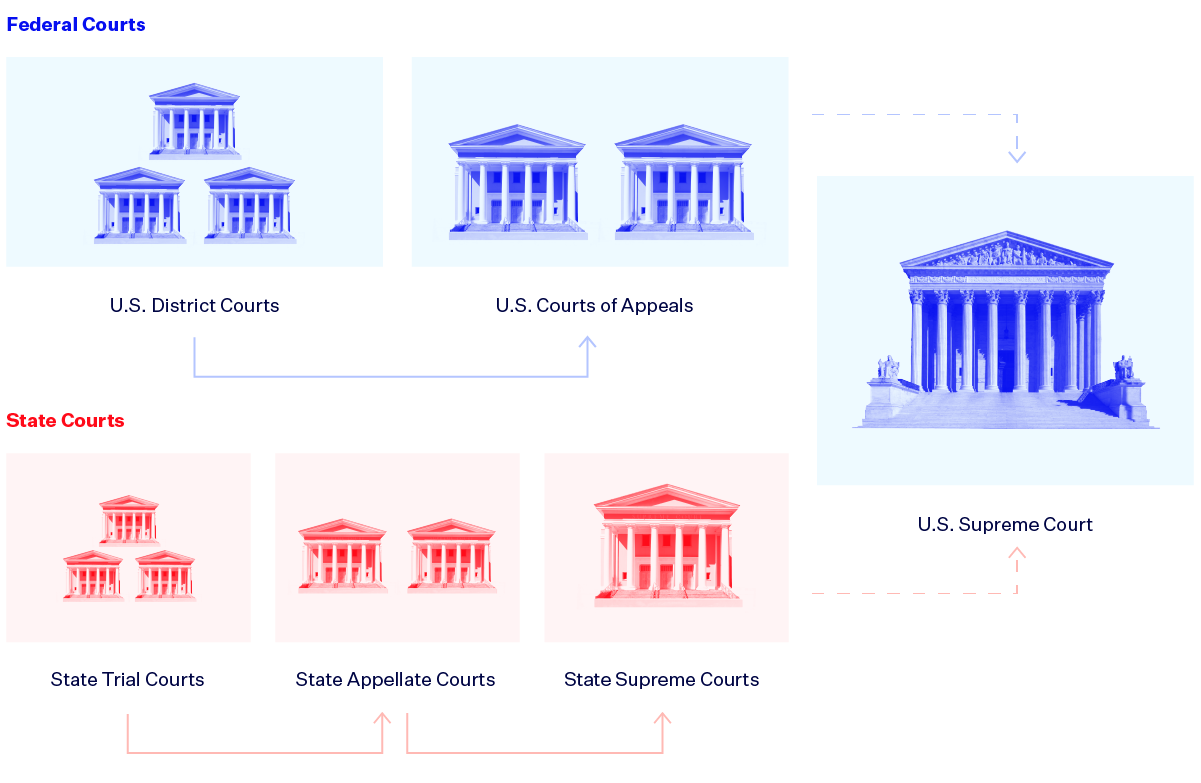

The United States is a dual court system where state and federal matters are handled separately.

There are two types of courts in the United States — state and federal. You can think about them as parallel tracks that can (though rarely) end up in the U.S. Supreme Court. Within the two respective tracks, there are three main levels: trial courts, appellate courts and the highest court for that respective track.

First, it’s important to understand jurisdiction: a court’s authority to hear cases and make legal decisions. Jurisdiction refers not only to a court’s geographic scope, but also whether there is a federal or state question at hand.

- To file a lawsuit in federal court, one must allege that there is a breach of federal law or the U.S. Constitution — these are cases that raise a “federal question.” Federal courts also hear a unique type of case involving “diversity of citizenship” where the case is between citizens of different states and potential damages exceed $75,000.

- In contrast, state courts are known as courts of general jurisdiction, meaning that one can raise any claim under state or federal law, except those that are under exclusive jurisdiction of federal courts.

In either federal or state court, a case starts at the lowest level: a U.S. district court or a state trial court, respectively. If a party disagrees with the outcome at the trial level, they can appeal it to a higher court and eventually petition all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court.

There are, of course, exceptions to these procedural rules. Here are two notable ones:

- The U.S. Supreme Court has original jurisdiction — the authority to be the first court to hear a case — over specific matters, such as disputes between states. In such rare instances, the U.S. Supreme Court would be the first and only court to hear the case.

- After a three-judge panel decides a redistricting case alleging constitutional violations, that case will automatically jump from district court to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court is forced to hear it, as well as three other types of cases that have a mandatory right to be heard by the highest court in the country.

The federal court system:

The federal court system has three main levels: district courts, circuit courts and the U.S. Supreme Court. Federal judges and Supreme Court justices are appointed by the president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate for a lifetime term.

District courts are the starting points for federal cases and where a trial takes place.

There are 94 active district courts across the country. Each U.S. state has between one and four districts, and Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia both have one district court. Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands also have their own territorial courts that function as district courts.

The number of judges varies widely by district. The U.S. District Court for the Central District of California and the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York have 28 judges each, the highest in the country. In contrast, the U.S. District Court for the District of Idaho only has two judges, as do several other district courts. District judges can also appoint magistrate judges, judicial officers who serve time-limited terms and assist with proceedings, due to the heavy workload at the trial level.

Circuit courts are the first level of appeal.

There are 13 circuit courts: 12 are organized geographically and one is the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which hears specific national jurisdiction cases including patent lawsuits and appeals from the U.S. Court of International Trade. For example, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals includes Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee, so any case decided within the nine districts in this geographic region will head to the 6th Circuit.

The number of judges in each circuit ranges from six judges in the 1st Circuit to 29 in the 9th Circuit. However, only three of these judges are randomly selected to form the panel that will decide the appeal. On rare occasions, after the three judge-panel makes a decision, a circuit court can rehear a case “en banc,” with the entire slate of judges reviewing the case.

The U.S. Supreme Court is the highest court and final level of appeal. It chooses which cases it hears.

Parties who disagree with the decision made by a circuit court can petition the U.S. Supreme Court to take the case. Less frequently, parties can petition the Supreme Court to review the decision made by a state Supreme Court if the case deals with a federal question.

Unlike intermediate appellate courts, the U.S. Supreme Court is not required to hear cases. Instead, parties ask the court to grant a writ of certiorari. The Supreme Court hears around 80 cases per year, selected from over 7,000 cases that it is asked to review.

There are no strict requirements for how the court selects its cases. It’s up to the discretion of the Supreme Court justices — four of the nine justices must vote in favor to accept a case. However, the Court typically accepts cases where there are conflicting decisions coming out of different circuits and/or there is a constitutional matter of national importance that needs to be resolved.

The state court system:

The state court system largely mirrors the structure of the federal court system in that it is generally composed of three main levels: trial courts, state appellate courts and a state Supreme Court. On rare occasions, a decision on federal matters made in a state Supreme Court will be petitioned to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Numerous states have separate probate courts focused on specific administrative matters. Each state runs its judicial system in a different way than its neighbor:

- For example, Colorado has subject-specific courts — on water, juvenile affairs in Denver, probate in Denver — as well as lower municipal and county courts.

- Meanwhile, the highest court in New York is called the Court of Appeals and the state’s Supreme Court is a trial-level court.

You can find the individual state courts’ structure and websites here.

While federal judges are nominated by the president, state judges are selected through various methods: governor or legislature appointments or elections. In 2022, there will be hundreds of judicial elections happening across the country where everyday residents can take a direct role in shaping the legal system.

Litigation is only going to ramp up this year. With this renewed understanding of the U.S. legal system, explore Democracy Docket’s Case pages and keep a close eye out for lawsuits that will determine the future of voting, elections and representation in the nation.

9b. The Structure of the Federal Courts

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. -Article III, Section 1, The Constitution of the United States

In the federal court system the Supreme Court has final appellate jurisdiction over all courts in the United States.

Notice that, according to the Constitution, Congress creates courts.

By implication, Congress also has the power to reorganize and even dismantle the court system. This clause provides one of many examples of the checks and balances in the Constitution, but it also reveals the Founders’ intent to grant greater powers to the legislative branch than to the judicial.

The fact that most of the basic court structure has changed little since it was created by the Judiciary Act of 1789 is an indication that Congress does not readily use this power. The relative independence of the court system, as well as the evolutionary power of the judicial branch, has been generally respected by members of subsequent Congresses.

Constitutional Courts

Courts established by the Judiciary Act of 1789 are called constitutional courts because they are mentioned in Article III (they are the “inferior courts” in the quote above).

Judges who preside over these courts are nominated by the president, confirmed by the Senate, and serve lifetime terms as long as they exhibit “good behavior.” Over the years, Congress has created other courts to handle cases for special purposes.

The first Territorial Supreme Court was formed for the Dakota Territory in 1861, but didn’t meet to hear appeals until 1867. This photograph shows the members of the court meeting to conduct business for the first time.

Legislative Courts

Those latter courts are referred to as “legislative courts.” For example, by the early 20th century, Congress had set up the U.S. territorial courts to hear federal cases in the territories that the United States began acquiring during the late 1800s. Judges for legislative courts are also appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, but they serve fixed, limited terms.

The Judicial Circuits

The Eighth Circuit includes the states of Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

The federal court system is divided into 12 geographic circuits. For example, Circuit One includes the New England states of Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. Circuit Nine includes seven states in the far western part of the country. Originally, each state in each circuit was to have one district court, where all federal cases from the state originated.

Over time, as the population grew, additional district courts were added. Today, a total of 94 district courts exist; they are staffed by more than 600 judges. Some circuits have more than others, based on population, but each circuit still has only one court of appeals. Cases not settled in the courts of appeal may be appealed further, but only to the Supreme Court.

District Courts and Courts of Appeals

Each U.S. district court has a different seal, a different jurisdiction, and different local rules.

Most cases that deal with federal questions or offenses begin in district courts, which are almost always granted original jurisdiction. District courts hear appeals cases only in the rare case of a constitutional question that may arise in state courts. About 80 percent of all federal cases are heard in district courts, and most of them end there. The number of judges assigned to district courts varies from two to twenty-eight, depending on caseloads and population.

Courts of Appeal

By the late 19th century, so many people were appealing their cases to the Supreme Court that Congress created another type of constitutional court, the courts of appeals. Today, along with 12 courts of appeals (one for each circuit), a thirteenth court, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, hears cases that deal with patents, contracts, and financial claims against the federal government.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, located in San Fransisco, is noted not only for its legal importance but its ornate architecture.

Courts of appeals never hear cases on original jurisdiction, and most appeals come from district courts within their circuits. They do sometimes hear cases from decisions of federal regulatory agencies as well.

Appeals courts have no juries, and panels of judges (usually three) decide the cases. Their decisions are almost always final. Their decisions may be appealed only to the Supreme Court, and because the Court is able to hear only a very small percentage of them, almost no cases go further than the appeals courts.

Thus, even though the Founders surely intended that Congress hold a great deal of power over the judicial branch, in reality the basic organization of federal courts has remained basically the same throughout U.S. history. Congress has created new courts and reorganized others, and the system has grown increasingly complex. The courts have a great deal of independence, however, and they have established the judicial branch as a strong coequal to Congress and the president. source