Discovery Abuse

Our blog for this week discusses discovery abuse. “Discovery” is the stage in a lawsuit where parties to a case have a right to obtain evidence from opposing parties and third parties which supports their claims and defenses. “Discovery abuse” occurs when the discovery process is wrongfully undermined. For example, in a case involving an injury sustained during a car accident, the plaintiff (the party bringing the lawsuit) may seek to obtain dash-cam footage from the defendant’s car which shows that the defendant ran a red light before crashing into and injuring the plaintiff. Setting aside any fifth amendment self-incrimination issues, if the lawyer for the defendant’s insurance company in that case refused to allow the plaintiff’s attorney to access the video footage, the defendant’s attorney might be said to have committed discovery abuse.

In our earlier blog article, “How To Compel Discovery In North Dakota,” we discussed what can be done to address and correct discovery abuses when they happen in litigation. You can read about that here. In this blog post, we discuss the significance of discovery abuse and go over some ways in which it can manifest itself.

The Significance Of Discovery Abuse

The topic of discovery abuse is significant both as it may relate to a particular lawsuit in question and also with respect to the implications it can have on justice at large. Our system of justice in the United States is described as an “adversarial legal system.” Adversarial legal systems are features of common law countries and are characterized by self-driven advocacy before a neutral and largely passive judge and jury. Unlike in civil law systems, where the judge may interview witnesses and serve as an “inquisitor,” in adversarial legal systems, the judge plays a minimal role in obtaining the evidence and facts of the case. This is how it usually works, despite what we may have seen on TV.

Because the judge plays a neutral role in the common law system, the burden of finding the truth largely rests with the parties’ attorneys in the case. Pursuant to North Dakota Rule of Civil Procedure 26(b)(1)(A), parties may obtain discovery from an adverse party regarding any nonprivileged (not otherwise protected by law) matter that is relevant to any party’s claim or defense. At the same time, attorneys must be zealous advocates for their clients, fully devoted to advancing their clients’ interests. See N.D.R. Prof. Conduct 1.3 cmt. 1 (“A lawyer should pursue a matter on behalf of a client despite opposition, obstruction or personal inconvenience to the lawyer, and take whatever lawful and ethical measures are required to vindicate a client’s cause or endeavor. A lawyer must also act with commitment and dedication to the interests of the client and with zeal in advocacy upon the client’s behalf.”).

So what happens when the truth is damaging to one of the parties; what happens, for example, when the dash-cam video shows that the light was red? This is where discovery abuse comes into play. Make no mistake: litigation is a fight, but it is not a game. As noted by the Court in Haeger v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 906 F. Supp. 2d 938, 941 (D. Ariz. 2012), “[l]itigation is not a game. It is the time-honored method of seeking the truth, finding the truth, and doing justice.” Discovery abuse might be likened to a situation where one party refuses to fight fairly. And where discovery is abused, justice is thwarted.

Some Typical Forms Of Discovery Abuse And Rule Violations

Discovery abuse oftentimes arises during written discovery. Written discovery refers to discovery that is achieved by way of written prompts served on an adverse party to a lawsuit. The most common forms of written discovery are interrogatories, requests for production, and requests for admission.

Interrogatories are written questions sent by one party to an adverse party and are governed by North Dakota Rule of Civil Procedure 33. Requests for production are written requests by a party to an adverse party asking that documents or electronically stored information be produced. They are governed by North Dakota Rule of Civil Procedure 34. Requests for admission are governed by North Dakota Rule of Civil Procedure 36 and are requests by one party to an adverse party that a factual statement be admitted as true.

In written discovery, discovery abuse can oftentimes manifest itself through boilerplate objections, as well as evasive, incomplete responses to interrogatories and requests for production.

Boilerplate Objections

Vague, repeated objections to discovery requests on the basis of “form and foundation” or on grounds that a request is “overly broad, vague, and unduly burdensome” are referred to as “boilerplate objections” and are improper under the North Dakota Rules of Civil Procedure. Grounds for objecting to interrogatories and requests for production must be stated with specificity and should not merely regurgitate stock phrases from the North Dakota Rules of Civil Procedure. For example, Rule 33(b)(4) of the North Dakota Rules of Civil Procedure requires that “the grounds for objecting to an interrogatory must be stated with specificity,” and Rule 34(b)(2)(B) provides that “for each item or category, the response must . . . state with specificity the grounds for objecting to the request.”

Courts have repeatedly held that boilerplate objections are improper and have stricken them accordingly. Just a few examples of Courts treating boilerplate objections with disdain include: Kooima v. Zacklift Intern., Inc., 209 F.R.D. 444, 446, 53 Fed. R. Serv. 3d 1315 (D.S.D. 2002) (noting that “boilerplate objections are unacceptable”); Frontier-Kemper Constructors, Inc. v. Elk Run Coal Co., Inc., 246 F.R.D. 522, 528 (S.D.W.Va.2007) (commenting that “there is abundant caselaw to the effect that boilerplate objections to Rule 34 document requests are inappropriate.”); and Perez Librado v. M.S. Carriers, Inc., 2003 WL 21075918 (N.D. Tex. 2003) (concluding that “a mere statement by a party that an interrogatory is overly broad, burdensome, oppressive and irrelevant is not adequate to voice a successful objection. Broad-based, non-specific objections are almost impossible to assess on their merits, and fall woefully short of the burden that must be borne by a party making an objection to an interrogatory or document request.”).

In one case, St. Paul Reinsurance Co., Ltd. v. Commercial Fin. Corp., 198 F.R.D. 508 (N.D. Iowa 2000), the Court crafted a special sanction for Counsel due to the boilerplate objections asserted in discovery, requiring that the lawyer write an article explaining why the objections were improper and submit it to the New York and Iowa Bar Journals. Other Courts have not been so kind, awarding severe monetary sanctions. Haeger, 906 F. Supp. 2d at 982. North Dakota Courts have a significant amount of discretion when choosing to award discovery sanctions. Benedict v. St. Luke’s Hosps., 365 N.W.2d 499, 504 (N.D. 1985).

Continuing with our previous example, let’s assume that the civil defendant is in possession of the dash-cam video footage of the accident and the plaintiff propounds the following interrogatory, receiving the following objection in response:

Interrogatory Number 1:

Please state whether you had any dash-cam or other video recording device in your vehicle at the time of the crash which captured footage of the accident.

Objection:

Objection to form and foundation. This request is overly broad, vague, unduly burdensome, and seeks information not reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence. This request also seeks information protected by attorney-client privilege, and attorney work product.

Here, we can see that the plaintiff is seeking to obtain discovery regarding factual matter that is relevant to his negligence claim. To succeed in his negligence claim, the plaintiff must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the defendant caused him harm by breaching a legal duty the defendant owed the plaintiff. If the defendant has video footage of the accident which helps the plaintiff show that the defendant breached his duty of care, the defendant must state as much in response to plaintiff’s request. As a result, in the first instance, the plaintiff’s discovery request is proper under North Rule Dakota Rule of Civil Procedure 26(b)(1)(A).

Second, we can see that the defendant has offered the plaintiff a boilerplate, obstructionist objection in response to the plaintiff’s legitimate request—on the basis of form, foundation, breadth, relevance, privilege, and work product. Contrary to Rule 33(b)(4), the defendant’s objection has not been stated with specificity. How is the discovery request overly broad? How would it be unduly burdensome for the defendant to state whether it possesses this video footage? The defendant has not provided any such information. Indeed, the plaintiff’s attorney is asking for nothing more than a simple statement.

With respect to the objection based on privilege and attorney work product, the defendant’s objection again falls short of what is required by the North Dakota Rules of Civil Procedure. Under Rule 26(b)(5)(A), as in this example, when a defendant withholds information that is otherwise discoverable by claiming that it is privileged or protected as attorney work product, the defendant must provide a description of the nature of the information in a manner that will allow the plaintiff to assess the claim. The North Dakota Supreme Court, in St. Alexius Med. Ctr. v. Nesvig, 2022 ND 65, ¶ 17, reiterated that “[t]he party claiming the privilege and desiring to exclude the evidence has the burden to prove the communications fall within the terms of the statute or rule granting the privilege.” Again, the defendant has provided nothing. This exemplifies a form of discovery abuse, even if it may be relatively common.

Evasive, Incomplete Responses

As with boilerplate objections, evasive, incomplete responses to discovery requests are improper under the North Dakota Rules of Civil Procedure, and can be forms of discovery abuse. In Voracheck v. Citizens State Bank of Lankin, 421 N.W.2d 45, 51 (N.D. 1988), the North Dakota Supreme Court noted that, with respect to discovery, even substantial compliance is not enough. Instead, complete and accurate compliance is required:

A party is not at liberty to “pick and choose” what information will be provided and what information will be withheld. Selective, substantial compliance is not enough; complete, accurate, and timely compliance is required by the rules. If a party were allowed to withhold certain information because it had provided some of the requested information, the discovery process would be rendered useless.

Rule 37(a)(4) of the North Dakota Rules of Civil Procedure provide that “an evasive or incomplete answer or response must be treated as a failure to answer or respond.” Similarly, under Rule 26(e)(1), where a party has become aware that a discovery response is incomplete or incorrect, that party must supplement or correct it.

Continuing with our previous example, let’s assume that the civil defendant decides, instead of fully answering the interrogatory, to merely state either that “this answer may be supplemented” or that “discovery is continuing.” These are, once again, relatively common discovery responses in litigation, but nonetheless can serve as forms of discovery abuse. North Dakota Rule of Civil Procedure 33(b)(3) requires that each interrogatory, to the extent that it is not objected to, be answered fully and in writing. Answering only that “discovery is continuing” or “this answer may be supplemented” are failures to respond to discovery. See also Carolina Cas. Ins. Co. v. Oahu Air Conditioning Serv., Inc., No. 2:13-CV-01378-WBS-AC, 2014 WL 4661979, at *4 (E.D. Cal. Sept. 17, 2014) (finding the response “discovery is continuing” insufficient and granting motion to compel); Azer v. Courthouse Racquetball Corp., 852 P.2d 75, 84 (Haw. Ct. App. 1993) (concluding that the response “discovery is continuing” was a failure to answer under Rule 37(a)(3)); K.R.S. v. Bedford Cmty. Sch. Dist., No. 4:13-CV-00147-HCA, 2014 WL 11513167, at *4 (S.D. Iowa Dec. 15, 2014) (“this response may be supplemented,” is improper, vague, boilerplate language that must be supplemented).

Conclusion

Discovery abuse is serious and thwarts the truth-finding process required for our common law legal system to produce just outcomes. The duty to make diligent efforts to respond completely to the substance of discovery does not stop with the North Dakota Rules of Civil Procedure. Rule 3.4 of the North Dakota Rules of Professional Conduct states, in subsection a, that “[a] lawyer shall not . . . unlawfully obstruct another party’s access to evidence,” and in subsection d provides that “[a] lawyer shall not . . . fail to make reasonably diligent efforts to comply with a legally proper discovery request by an opposing party.” As officers of the Court, lawyers have a duty to help ensure the integrity of the legal system, and that duty becomes especially evident in discovery.

In this blog article, we’ve discussed why discovery abuse is important, and gone over some examples of how it can manifest itself. The information contained in this article and on this website is for informational purposes only and not for the purpose of providing legal advice. Each case is different, and this article is meant only to provide a brief summary of the law. You should contact an attorney to obtain advice with respect to your particular case.

cited https://www.swlattorneys.com/discovery-abuse/

Discovery Abuse – What To Do When Defendants Withhold Applicable Insurance Policies

A lawsuit begins once a plaintiff initiates a civil action against one or more defendants. As soon as the defendant answers, both parties begin to exchange written discovery requests to solicit specific information from the opposing party that is relevant to the litigation. The information sought can be in the form of documents or other tangible items such as video or audio recordings, bank statements, tax documents, letters, emails, etc. Additionally, the Texas Rules of Civil Procedure allow parties to solicit admissions, interrogatories, and other information through depositions. Each of these methods seeks to develop the factual circumstances surrounding the lawsuit to ensure that the parties attorneys are informed. This helps prepare a game plan for the attorneys to present their version of what actually happened to their clients.

Withholding Information on Documents from Discovery Requests

The obvious question then becomes: what happens if the opposing party withholds discoverable information—such as an insurance policy?

The existence of an insurance policy can be key information in determining the defendant’s ability to pay a judgment or settlement based on the merits of the case. Namely, an insurer has a duty to defend claims against one of their insured and the existence of a liability insurance policy may be the difference between the injured party being able to recover damages or not.

When one of the parties does not cooperate with discovery requests or fails to answer the requests thoroughly, the opposing party has a few avenues for redress. The first is to “meet and confer.” This method is an informal attempt to resolve discovery disputes before the parties involve the court. The purpose is to save the parties time and money and increase the judicial economy by encouraging a resolution of disputes without the need for court intervention. If this is unsuccessful because one party contends certain information is not discoverable, the complaining party may then file a motion to compel discovery with the court.

What is a Motion to Compel?

A motion to compel operates as a formal request for the court to require the non-producing party to comply with the discovery requests. This is done by requiring that the offending party must produce whatever information they have withheld. The party filing this motion must prove that they have requested discoverable and relevant information that was withheld. The court, after hearing evidence of one party’s attempts to get discoverable information and the other party’s refusal or neglect to provide, will determine whether the non-producing party is abusing the discovery process and may compel that party to produce discoverable information—such as an applicable insurance policy. A determination that the withholding of information is proper ends the conflict; however, a determination that the withheld information was discoverable results in a granted motion to compel, and nonadherence to this ruling results in court-imposed sanctions against the nonadherent party.

Court Sanctions

Determining that the non-producing party has abused discovery can lead to sanctions by the court that takes various forms. One method of sanctioning the non-producing party is to award the party seeking discoverable information reasonable attorney’s fees to compensate them for the time they spent preparing pleadings and spending time compelling the information. Other sanctions include disallowing further discovery of a particular kind by the disobedient party, an order refusing the disobedient party from supporting or opposing designated claims or defenses, or an order staying the proceedings until the order is obeyed. These sanctions handicap the disobedient party’s ability to conduct cost-effective cases and place them in a position where they are unable to conclude a case for their client until they comply.

In the end, the legal community is tight-knit. Withholding pertinent information from opposing counsel will not get anyone very far, and the risks far outweigh the reward. In that a liability insurance policy is withheld, there are safeguards in place to ensure that counsel acting in bad faith through withholding such information is held accountable and forced to comply—or face sanctions by the court. cited https://wattsguerra.com/discovery-abuse-what-to-do-when-defendants-withhold-applicable-insurance-policies/

National District Attorneys Association puts out its standards

National Prosecution Standards – NDD can be found here

The Ethical Obligations of Prosecutors in Cases Involving Postconviction Claims of Innocence

Prosecutor’s Duty Duty to Disclose Exculpatory Evidence Fordham Law Review PDF

Chapter 14 Disclosure of Exculpatory and Impeachment Information PDF

Journal of Forensic & Investigative Accounting

Fighting Discovery Abuse in Litigation

Forensic accountants can serve a number of important roles in a legal dispute. In these roles, forensic accountants often provide:

1) discovery assistance (e.g., knowing what specific information to request and identifying the appropriate individuals to depose or interview);

2) development of a detailed, straightforward analysis and report that communicates appropriate findings and conclusions; and

3) the delivery of effective testimony whether it be in deposition, arbitration, trial or other dispute resolution forums. Since discovery accounts for the majority of the cost of civil litigation (as much as 90 percent in complex cases), 1 the role that forensic accountants play in the discovery process is particularly significant.

Discovery is the formal process that litigants use to obtain information from opposing parties (Sinclair, 2008; Crumbley et.al., 2013). The discovery process, in theory, enables the parties to know before trial begins what evidence may be presented. This process minimizes surprises, lowers the transaction costs of dispute resolution, increases the percentage of settled cases, improves the accuracy of trials and filters out frivolous disputes (Kim and Ryu, 2002).

*The authors are, respectively, Professor of Accounting at Florida Atlantic University, Associate Professor of Accounting at the University of South Florida-St. Petersburg, and Associate Professor of Accounting at Florida Atlantic University.

1Memorandum from Paul Niemeyer, Chair, Advisory Comm. on Civil Rules to Hon. Anthony J. Scirica, Chair, Comm. on Rules of Practice and Procedure (May 11, 1999), 192 F.R.D. 340, 357 (2000).

Abusive tactics are fostered by the justice system itself. First, attorneys know that lawyers are given multiple opportunities to comply with discovery requests before judicial enforcement of discovery obligations is imposed by the court (Lee and Willging, 2010; Mehr, 2012). Second, the generally accepted law firm economic model provides an incentive to increase the costs of discovery as lawyers may use it as a way to increase the number of hours they bill to clients (Lee and Willging, 2010; Mehr, 2012). Since our legal system simply cannot remove discovery from the process, forensic accountants, lawyers, and judges must use tools at their disposal to enforce compliance with the rules, consistent with the spirit of discovery.

2See Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(f) (describing the mandatory conference opposing parties must have to decide the time table of discovery as well as the general issues that will be pursued).

The purpose of this article is to show how litigation support tools can be combined with standard discovery techniques to obtain critical evidence from an opposing party bent on discovery abuse. An enhanced understanding of these issues will place forensic accountants in a better position to assist attorneys in litigation. Moreover, the use of various litigation support tools will improve attorneys’ chances of securing valuable evidence that they otherwise would

We first discuss discovery devices and various methods that have been used to abuse the discovery process. We then offer a collaborative or team approach and provide tactics to fight discovery abuse.

The process of discovery begins with an initial meeting of the parties to the lawsuit (hereinafter referred to as “parties”) during which they are required to make or arrange for mandatory disclosures and develop a proposed discovery plan. The timing for discovery should be established. The judge uses the plan to implement the timeline so that discovery is completed by the agreed-upon date. 3 After the initial meeting, mandatory initial disclosures occur and must

3 Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(f).

4 Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a)(1)(E).

5 Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a)(1)(E).

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure allow a litigant to pursue information from the other party by, for example, depositions, interrogatories, document production requests, requests for physical or mental examination, and requests for admission. Litigants must even provide their opponents with information that may not be admissible at trial if the information could reasonably lead to the discovery of admissible evidence. 6

Depositions require the opposing party or third-party witness to be placed under oath before trial and answer questions posed by attorneys from both sides of the case. Anyone who may have knowledge or expertise pertinent to the case may be deposed, including expert witnesses such as forensic accountants. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure allow each party up to ten depositions. No limit exists on the number of questions that may be asked, but there is

6 Some information is protected from discovery. Reasons why information may be undiscoverable include some legal privilege (e.g., attorney-client privilege)(Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(1)), the work product rule (trial preparation materials)(Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(3)), non-testifying experts (Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(4)(D)), and court-imposed limits for good cause (Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(2) and 26(c)). permission by the court, or consent of the other party to serve a larger number.7 Sometimes responses to interrogatories are verified by inclusion in an affidavit.

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provide that when interrogatories seek disclosure of information in corporate records, the party upon whom the request is served can designate the records that contain the answers. Objections to questions in interrogatories can be raised, and a party need not answer until a court determines their validity.

A request for the production of documents is a request made to a party in a lawsuit to turn over copies of any evidence in the form of paper documents, electronically stored information (ESI), or other items. A request for the production of documents usually contains separately- numbered requests. The request specifies a certain class or type of document, but often is broadly worded to cover as many documents as possible. Examples include copies of bank statements, insurance policies, or other financial or business documents related to the case. A request “must describe with reasonable particularity each item … to be inspected.” 8

A request for admissions is a list of questions, each of which is stated as a declaration which the responding party must admit, deny, or state the reason he or she cannot admit or deny. Instead of responding to each question, a responding party also may object to the request for admission itself. Requests are limited to facts, the application of law to facts, opinions about either the facts or the application of law to the facts, and the genuineness of any described

7 Fed. R. Civ. P. 33. 8 Fed. R. Civ. P. 34(b)(1)(A). 9 Fed. R. Civ. P. 34(b)(1)(B).

One persistent criticism of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is that discovery provisions do not quell the abusive discovery practices of litigants. Discovery abuse or predatory discovery

10 Fed. R. Civ. P. 36(a)(1).

11 This term originates from Marrese v. Amer. Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 726 F. 2d 1150, 1162 (7th Cir. 1984). Predatory discovery is “sought not to gather evidence that will help the party seeking discovery to prevail on the merits of his case but to coerce his opposition to settle regardless of the merits ….”.

12Defendants can exploit the broad relevance standard under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26(b) by inundating plaintiffs with information. This exploitation is particularly likely to be acute in situations in which plaintiffs need discovery the most because they do not know enough about the defendant’s internal workings or documents to draft narrower requests. Many plaintiffs may simply buckle under the sheer volume of information and the costs of sifting through it (Glover, 2012).

13 Some of the more egregious federal cases in which a party failed to comply with a court order compelling discovery include: Wanderer v. Johnston, 910 F. 2d 652 (9 th Cir. 1990) (defendants refused to produce documents even though nine court orders had been issued to do so-the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed entry of a default judgment of $25 million in plaintiffs’ favor) and John B. Hull, Inc. v. Waterbury Petroleum Prod., 845 F. 2d

1172, 1177 (2d Cir. 1988) (upholding sanction of dismissal of third-party plaintiff’s complaint and award of attorney’s fees and costs where the third party disregarded court orders). Journal of Forensic & Investigative Accounting Vol. 6, Issue 2, July – December, 2014

Interrogatories represent a comparatively inexpensive and efficient means of obtaining

Interrogatories are the most abused discovery device. Attorneys ask questions drawn

Some attorneys have exploited judicial conflict concerning Rule 33(a) which states that

14 St. Paul Fire and Marine Insurance Co. v. Birch, Stewart, Kolasch & Birch, LLP, 217 F.R.D. 288 (D. Mass. 2003); James Moore. 7 Moore’s Federal Practice §33.30[1]. Mathew Bender, 3rd ed., 1997 and Supp. 2004.

An alternate interpretation of Rule 33(a) is that the word “party” may refer to an entire side of a dispute collectively rather than to the individual actors that are members of each side. 15

The choice of interpretation of Rule 33(a) has implications for predatory discovery. The broad construction permits parties to file larger numbers of interrogatories and often more than is required for adequate discovery. This practice is particularly true for “big ticket cases where the stakes motivate parties to litigate by hook or crook” (Yoo, 2008). Interrogatory abuse also can affect smaller cases where well-heeled parties can protract discovery beyond the means of less wealthy parties (Yoo, 2008).

A second technique employed by litigants is the outright refusal to answer interrogatories (or take excessive time to answer). This conduct can buy a defendant a substantial amount of time and wear down the plaintiff as the latter seeks court sanctions. In National Hockey League v. Metropolitan Hockey Club, Inc.,16 the plaintiffs failed to answer various interrogatories submitted by the defendants, continually flouting the trial court’s discovery orders and timelines.

15 Zito v. Leasecomm Corp., 233 F.R.D. 395, 399 (S.D.N.Y. 2006) (a civil RICO case brought by more than 200 individual plaintiffs as the result of an alleged fraudulent e-commerce leasing scheme); Charles Wright, ArthurMiller and Richard Marcus. 8A Federal Practice and Procedure §2168.1,West 2d ed. 1994 and Supp. 2007.

16 427 U.S. 639 (1976).

17 965 F. 2d 298 (7 th Cir. 1992). In that case, the plaintiffs, Govas and Yiannias, filed a suit alleging federal securities law fraud, common law fraud, and RICO violations. After the plaintiffs refused to answer interrogatoriesfor almost two years, defendants moved to have the case dismissed. The federal district court and appellate court upheld dismissal.

Depositions are an effective discovery device that is used to collect information that has

One type of discovery abuse is vulgar and abusive language and physical threats. In

Physical threats are sometimes employed to intimidate a deponent and opposing counsel.

A second category of predatory deposition abuse involves instructions not to answer

A third type of predatory practice in depositions involves witness coaching, interrupting a

Another Rambo tactic is to hold private conferences with the client-deponent during the

Although somewhat rare, one last category of deposition discovery abuse is physical

In litigation, forensic accountants and the attorneys for whom they work depend to a

One common discovery abuse is the use of overbroad document production requests in an

A second abuse involving document production requests is evasive or incomplete

The Federal Rules contain an express prohibition against evasive responses and provide

A third abusive practice is the use of boilerplate objections to document requests. Parties

A fourth predatory practice is for the party who has been requested to produce documents

A fifth abusive technique is a document dump. A responding party provides thousands

Numerous tactics can be used to respond to predatory discovery practices. These

Adoption of a collaborative or team approach yields three major benefits to the discovery

The great Chinese warrior Sun Tzu said, “Know thy self, know thy enemy. Victorious

The forensic accountant, possibly with the guidance of counsel, should collect as much

If possible, answer such questions as what types of objections, if any, did counsel raise to

Before commencing the discovery process, it may also be advisable to collect as much

1. the nature of the entity’s business, industry, competition, market share, and major

2. the entity’s capital and/or financing structure (including bank accounts maintained and

3. the entity’s organizational structure including parent, subsidiaries (domestic and

4. the entity’s regulatory environment (publicly available documents such as Form 10-K

5. the flow of funds through the business;

6. nature of the decision-making process at the executive level;

7. production methods (if relevant);

8. purchasing methods, e.g., contract, bidding (if relevant);

9. employee compensation methods, e.g., salary, hourly, commission, etc. (if relevant);

10. accounting information system and internal controls and accounting records

a.

the forensic accountant’s understanding will focus on these and other

How is the type of transaction initiated and authorized? What processing

What records and documents are involved? How are documents filed and

Financial statement analysis should be undertaken to determine the financial condition of

Adoption of a collaborative or team approach also entails using precise discovery

A collaborative or team approach also entails quick responses to any delays, omissions,

The litigation team may think of and treat discovery abuse as a fraud scheme. Discovery

Document or evidence withholding during discovery may take these forms:

1. Sanitized document or data production — involves removal of data or facts detrimental

2. Intentionally incomplete production — entails leaving out or omitting any record of key

3. Unbalanced production — involves creating documents and/or data that favor the

A common sense reaction to suspected withholding during discovery is a careful

Another part of deflecting discovery abuse is fashioning a framework from the outset in

A second tactic in combating abusive discovery involves making a good record.

A third tactic is to insist that the opponent provide a “privilege log.” This lists the

A fourth step is to seek a protective order from the trial court. Given the abusive conduct

The most potent tactic is to seek sanctions for predatory discovery. Federal courts have

1.

directing that matters embraced in a court order be taken as established for purposes

2.

prohibiting the discovery abuser from supporting or opposing designated claims or

3.

striking pleadings in whole or in part;

4.

staying further proceedings until a court order is obeyed;

5.

dismissing the action in whole or in part;

6.

rendering a default judgment against the abusing party;

7.

treating as contempt of court the failure to obey a court order except the failure to

8.

ordering expenses to be paid by the misbehaving party.

To Learn More…. Read MORE Below and click the links Below

Abuse & Neglect – The Mandated Reporters (Police, D.A & Medical & the Bad Actors)

Mandated Reporter Laws – Nurses, District Attorney’s, and Police should listen up

If You Would Like to Learn More About: The California Mandated Reporting LawClick Here

To Read the Penal Code § 11164-11166 – Child Abuse or Neglect Reporting Act – California Penal Code 11164-11166Article 2.5. (CANRA) Click Here

Mandated Reporter formMandated ReporterFORM SS 8572.pdf – The Child Abuse

ALL POLICE CHIEFS, SHERIFFS AND COUNTY WELFARE DEPARTMENTS INFO BULLETIN:

Click Here Officers and DA’s for (Procedure to Follow)

It Only Takes a Minute to Make a Difference in the Life of a Child learn more below

You can learn more here California Child Abuse and Neglect Reporting Law its a PDF file

Learn More About True Threats Here below….

We also have the The Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) – 1st Amendment

CURRENT TEST = We also have the The ‘Brandenburg test’ for incitement to violence – 1st Amendment

We also have the The Incitement to Imminent Lawless Action Test– 1st Amendment

We also have the True Threats – Virginia v. Black is most comprehensive Supreme Court definition – 1st Amendment

We also have the Watts v. United States – True Threat Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Clear and Present Danger Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Gravity of the Evil Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Elonis v. United States (2015) – Threats – 1st Amendment

Learn More About What is Obscene…. be careful about education it may enlighten you

We also have the Miller v. California – 3 Prong Obscenity Test (Miller Test) – 1st Amendment

We also have the Obscenity and Pornography – 1st Amendment

Learn More About Police, The Government Officials and You….

$$ Retaliatory Arrests and Prosecution $$

Anti-SLAPP Law in California

Freedom of Assembly – Peaceful Assembly – 1st Amendment Right

We also have the Brayshaw v. City of Tallahassee – 1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Publius v. Boyer-Vine –1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, Florida (2018) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Nieves v. Bartlett (2019) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Hartman v. Moore (2006) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

We also have the Reichle v. Howards (2012) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

Freedom of the Press – Flyers, Newspaper, Leaflets, Peaceful Assembly – 1$t Amendment – Learn More Here

Vermont’s Top Court Weighs: Are KKK Fliers – 1st Amendment Protected Speech

We also have the Insulting letters to politician’s home are constitutionally protected, unless they are ‘true threats’ – Letters to Politicians Homes – 1st Amendment

We also have the First Amendment Encyclopedia very comprehensive – 1st Amendment

Dwayne Furlow v. Jon Belmar – Police Warrant – Immunity Fail – 4th, 5th, & 14th Amendment

ARE PEOPLE LYING ON YOU? CAN YOU PROVE IT? IF YES…. THEN YOU ARE IN LUCK!

Penal Code 118 PC – California Penalty of “Perjury” Law

Federal Perjury – Definition by Law

Penal Code 132 PC – Offering False Evidence

Penal Code 134 PC – Preparing False Evidence

Penal Code 118.1 PC – Police Officer$ Filing False Report$

Spencer v. Peters– Police Fabrication of Evidence – 14th Amendment

Penal Code 148.5 PC – Making a False Police Report in California

Penal Code 115 PC – Filing a False Document in California

Sanctions and Attorney Fee Recovery for Bad Actors

FAM § 3027.1 – Attorney’s Fees and Sanctions For False Child Abuse Allegations – Family Code 3027.1 – Click Here

FAM § 271 – Awarding Attorney Fees– Family Code 271 Family Court Sanction Click Here

Awarding Discovery Based Sanctions in Family Law Cases – Click Here

FAM § 2030 – Bringing Fairness & Fee Recovery – Click Here

Zamos v. Stroud – District Attorney Liable for Bad Faith Action – Click Here

Mi$Conduct – Pro$ecutorial Mi$Conduct

Prosecutor$

Attorney Rule$ of Engagement – Government (A.K.A. THE PRO$UCTOR) and Public/Private Attorney

What is a Fiduciary Duty; Breach of Fiduciary Duty

The Attorney’s Sworn Oath

Malicious Prosecution / Prosecutorial Misconduct – Know What it is!

New Supreme Court Ruling – makes it easier to sue police

Possible courses of action Prosecutorial Misconduct

Misconduct by Judges & Prosecutor – Rules of Professional Conduct

Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

Information On Prosecutorial Discretion

Fighting Discovery Abuse in Litigation – Forensic & Investigative Accounting – Click Here

Criminal Motions § 1:9 – Motion for Recusal of Prosecutor

Pen. Code, § 1424 – Recusal of Prosecutor

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

National District Attorneys Association puts out its standards

National Prosecution Standards – NDD can be found here

The Ethical Obligations of Prosecutors in Cases Involving Postconviction Claims of Innocence

ABA – Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

Prosecutor’s Duty Duty to Disclose Exculpatory Evidence Fordham Law Review PDF

Chapter 14 Disclosure of Exculpatory and Impeachment Information PDF

Mi$Conduct – Judicial Mi$Conduct

Judge$

Prosecution Of Judges For Corrupt Practice$

Code of Conduct for United States Judge$

Disqualification of a Judge for Prejudice

Judicial Immunity from Civil and Criminal Liability

Recusal of Judge – CCP § 170.1 – Removal a Judge – How to Remove a Judge

l292 Disqualification of Judicial Officer – C.C.P. 170.6 Form

How to File a Complaint Against a Judge in California?

Commission on Judicial Performance – Judge Complaint Online Form

Why Judges, District Attorneys or Attorneys Must Sometimes Recuse Themselves

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

Misconduct by Government Know Your Rights Click Here (must read!)

Under 42 U.S.C. $ection 1983 – Recoverable Damage$

42 U.S. Code § 1983 – Civil Action for Deprivation of Right$

18 U.S. Code § 242 – Deprivation of Right$ Under Color of Law

18 U.S. Code § 241 – Conspiracy against Right$

Section 1983 Lawsuit – How to Bring a Civil Rights Claim

Suing for Misconduct – Know More of Your Right$

Police Misconduct in California – How to Bring a Lawsuit

How to File a complaint of Police Misconduct? (Tort Claim Forms here as well)

Deprivation of Rights – Under Color of the Law

What is Sua Sponte and How is it Used in a California Court?

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors

and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

Anti-SLAPP Law in California

Freedom of Assembly – Peaceful Assembly – 1st Amendment Right

How to Recover “Punitive Damages” in a California Personal Injury Case

Pro Se Forms and Forms Information(Tort Claim Forms here as well)

What is Tort?

PARENT CASE LAW

RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR CHILDREN &

YOUR CONSTITUIONAL RIGHT$ + RULING$

YOU CANNOT GET BACK TIME BUT YOU CAN HIT THOSE IMMORAL NON CIVIC MINDED PUNKS WHERE THEY WILL FEEL YOU = THEIR BANK

Family Law Appeal – Learn about appealing a Family Court Decision Here

9.3 Section 1983 Claim Against Defendant as (Individuals) —

14th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

Amdt5.4.5.6.2 – Parental and Children’s Rights –

5th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

9.32 – Interference with Parent / Child Relationship –

14th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

California Civil Code Section 52.1

Interference with exercise or enjoyment of individual rights

Parent’s Rights & Children’s Bill of Rights

SCOTUS RULINGS FOR YOUR PARENT RIGHTS

SEARCH of our site for all articles relating for PARENTS RIGHTS Help!

Child’s Best Interest in Custody Cases

Are You From Out of State (California)? FL-105 GC-120(A)

Declaration Under Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction and Enforcement Act (UCCJEA)

Learn More:Family Law Appeal

Necessity Defense in Criminal Cases

GRANDPARENT CASE LAW

Do Grandparents Have Visitation Rights? If there is an Established Relationship then Yes

Third “PRESUMED PARENT” Family Code 7612(C) – Requires Established Relationship Required

Cal State Bar PDF to read about Three Parent Law –

The State Bar of California family law news issue4 2017 vol. 39, no. 4.pdf

Distinguishing Request for Custody from Request for Visitation

Troxel v. Granville, 530 U.S. 57 (2000) – Grandparents – 14th Amendment

S.F. Human Servs. Agency v. Christine C. (In re Caden C.)

9.32 Particular Rights – Fourteenth Amendment – Interference with Parent / Child Relationship

Child’s Best Interest in Custody Cases

When is a Joinder in a Family Law Case Appropriate? – Reason for Joinder

Joinder In Family Law Cases – CRC Rule 5.24

GrandParents Rights To Visit

Family Law Packet OC Resource Center

Family Law Packet SB Resource Center

Motion to vacate an adverse judgment

Mandatory Joinder vs Permissive Joinder – Compulsory vs Dismissive Joinder

When is a Joinder in a Family Law Case Appropriate?

Kyle O. v. Donald R. (2000) 85 Cal.App.4th 848

Punsly v. Ho (2001) 87 Cal.App.4th 1099

Zauseta v. Zauseta (2002) 102 Cal.App.4th 1242

S.F. Human Servs. Agency v. Christine C. (In re Caden C.)

DUE PROCESS READS>>>>>>

Due Process vs Substantive Due Process learn more HERE

Understanding Due Process – This clause caused over 200 overturns in just DNA alone Click Here

Mathews v. Eldridge – Due Process – 5th & 14th Amendment Mathews Test – 3 Part Test– Amdt5.4.5.4.2 Mathews Test

“Unfriending” Evidence – 5th Amendment

At the Intersection of Technology and Law

We also have the Introducing TEXT & EMAIL Digital Evidence in California Courts – 1st Amendment

so if you are interested in learning about Introducing Digital Evidence in California State Courts

click here for SCOTUS rulings

Retrieving Evidence / Internal Investigation Case

Conviction Integrity Unit (“CIU”) of the Orange County District Attorney OCDA – Click Here

Fighting Discovery Abuse in Litigation – Forensic & Investigative Accounting – Click Here

Orange County Data, BodyCam, Police Report, Incident Reports,

and all other available known requests for data below:

APPLICATION TO EXAMINE LOCAL ARREST RECORD UNDER CPC 13321 Click Here

Learn About Policy 814: Discovery Requests OCDA Office – Click Here

Request for Proof In-Custody Form Click Here

Request for Clearance Letter Form Click Here

Application to Obtain Copy of State Summary of Criminal HistoryForm Click Here

Request Authorization Form Release of Case Information – Click Here

Texts / Emails AS EVIDENCE: Authenticating Texts for California Courts

Can I Use Text Messages in My California Divorce?

Two-Steps And Voila: How To Authenticate Text Messages

How Your Texts Can Be Used As Evidence?

California Supreme Court Rules:

Text Messages Sent on Private Government Employees Lines

Subject to Open Records Requests

case law: City of San Jose v. Superior Court – Releasing Private Text/Phone Records of Government Employees

Public Records Practices After the San Jose Decision

The Decision Briefing Merits After the San Jose Decision

CPRA Public Records Act Data Request – Click Here

Here is the Public Records Service Act Portal for all of CALIFORNIA Click Here

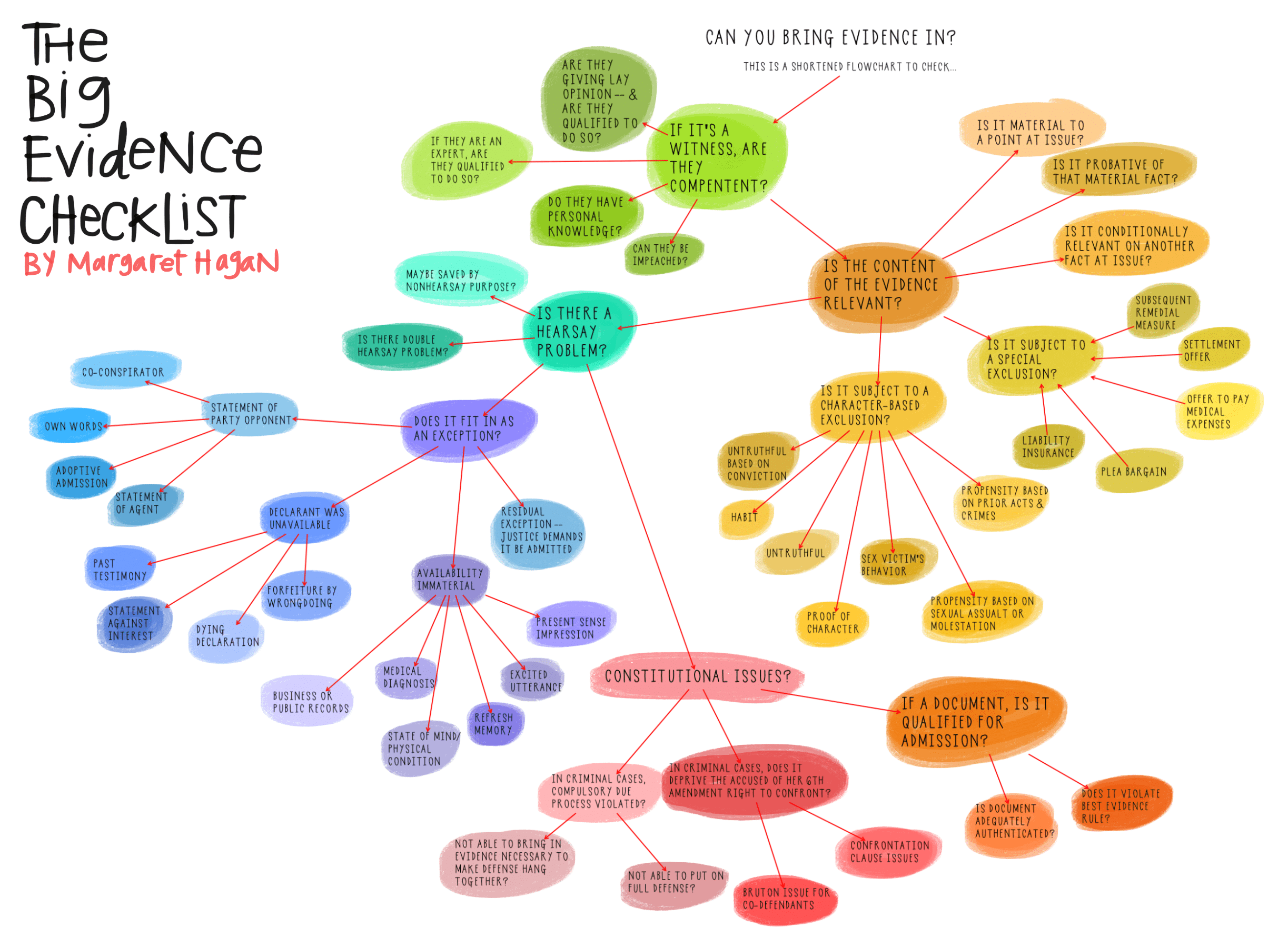

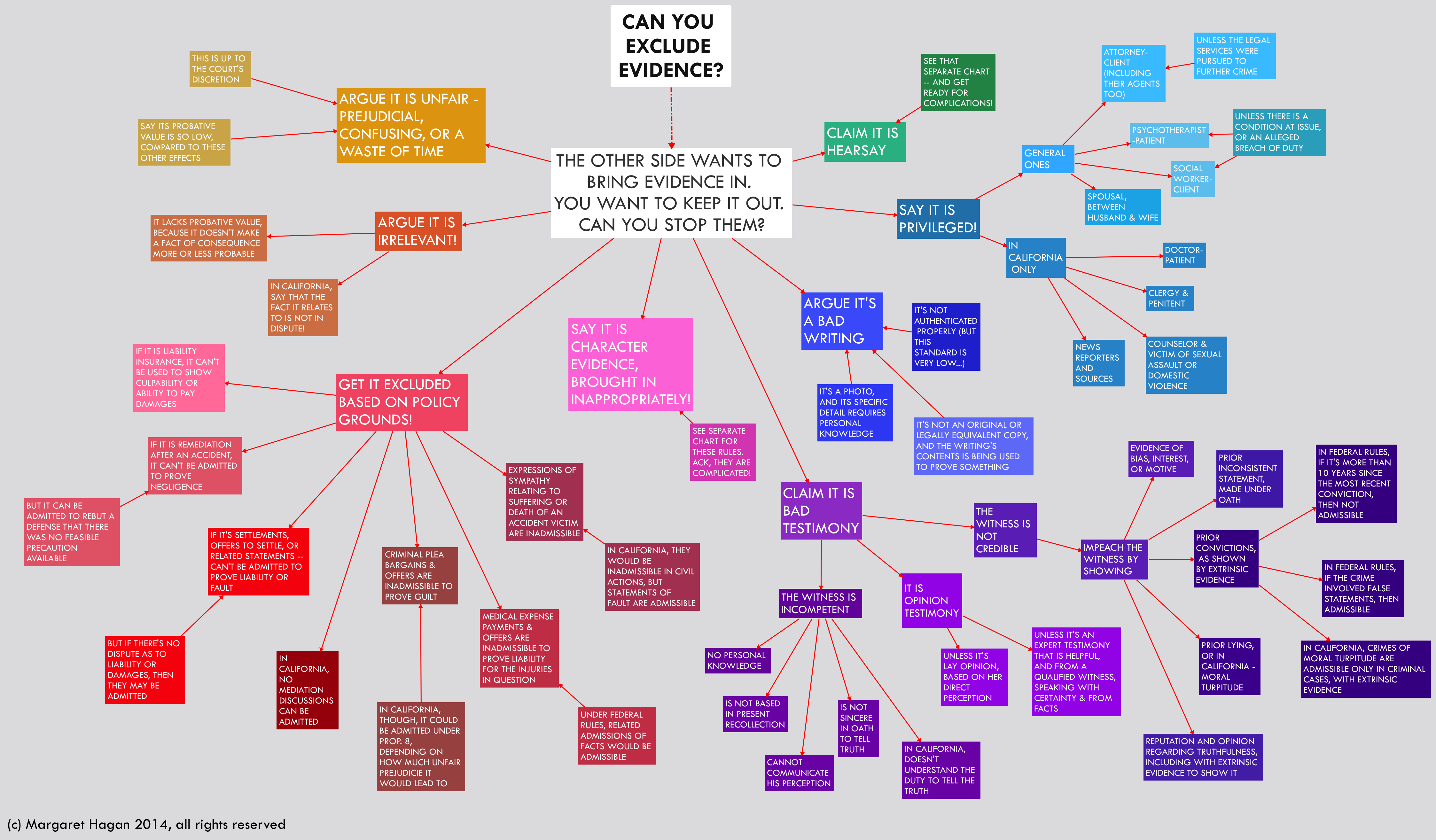

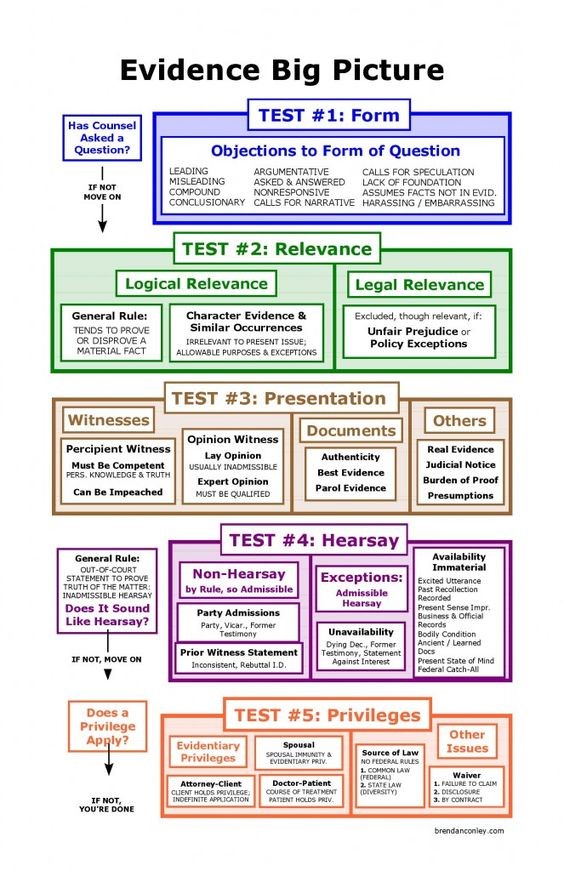

Rules of Admissibility – Evidence Admissibility

Confrontation Clause – Sixth Amendment

Exceptions To The Hearsay Rule – Confronting Evidence

Prosecutor’s Obligation to Disclose Exculpatory Evidence

Successful Brady/Napue Cases – Suppression of Evidence

Cases Remanded or Hearing Granted Based on Brady/Napue Claims

Unsuccessful But Instructive Brady/Napue Cases

ABA – Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

Frivolous, Meritless or Malicious Prosecution – fiduciary duty

Appealing/Contesting Case/Order/Judgment/Charge/ Suppressing Evidence

First Things First: What Can Be Appealed and What it Takes to Get Started – Click Here

Options to Appealing– Fighting A Judgment Without Filing An Appeal Settlement Or Mediation

Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 1008 Motion to Reconsider

Penal Code 1385 – Dismissal of the Action for Want of Prosecution or Otherwise

Penal Code 1538.5 – Motion To Suppress Evidence in a California Criminal Case

CACI No. 1501 – Wrongful Use of Civil Proceedings

Penal Code “995 Motions” in California – Motion to Dismiss

WIC § 700.1 – If Court Grants Motion to Suppress as Evidence

Suppression Of Exculpatory Evidence / Presentation Of False Or Misleading Evidence – Click Here

Notice of Appeal — Felony (Defendant) (CR-120) 1237, 1237.5, 1538.5(m) – Click Here

California Motions in Limine – What is a Motion in Limine?

Cleaning Up Your Record

Penal Code 851.8 PC – Certificate of Factual Innocence in California

Petition to Seal and Destroy Adult Arrest Records – Download the PC 851.8 BCIA 8270 Form Here

SB 393: The Consumer Arrest Record Equity Act – 851.87 – 851.92 & 1000.4 – 11105 – CARE ACT

Expungement California – How to Clear Criminal Records Under Penal Code 1203.4 PC

How to Vacate a Criminal Conviction in California – Penal Code 1473.7 PC

Seal & Destroy a Criminal Record

Cleaning Up Your Criminal Record in California (focus OC County)

Governor Pardons – What Does A Governor’s Pardon Do

How to Get a Sentence Commuted (Executive Clemency) in California

How to Reduce a Felony to a Misdemeanor – Penal Code 17b PC Motion

Epic Criminal / Civil Right$ SCOTUS Help – Click Here

Epic Criminal / Civil Right$ SCOTUS Help – Click Here

Epic Parents SCOTUS Ruling – Parental Right$ Help – Click Here

Epic Parents SCOTUS Ruling – Parental Right$ Help – Click Here

Judge’s & Prosecutor’s Jurisdiction– SCOTUS RULINGS on

Judge’s & Prosecutor’s Jurisdiction– SCOTUS RULINGS on

Prosecutional Misconduct – SCOTUS Rulings re: Prosecutors

Prosecutional Misconduct – SCOTUS Rulings re: Prosecutors

Family Treatment Court Best Practice Standards

Download Here this Recommended Citation

Please take time to learn new UPCOMING

The PROPOSED Parental Rights Amendment

to the US CONSTITUTION Click Here to visit their site

The proposed Parental Rights Amendment will specifically add parental rights in the text of the U.S. Constitution, protecting these rights for both current and future generations.

The Parental Rights Amendment is currently in the U.S. Senate, and is being introduced in the U.S. House.