Introducing Digital Evidence in California State Courts

A text message is a writing within the meaning of Evidence Code section 250, which may not be admitted in evidence without being authenticated. (Stockinger v. Feather River Community College (2003) 111 Cal.App.4th 1014, 1027–1028.)

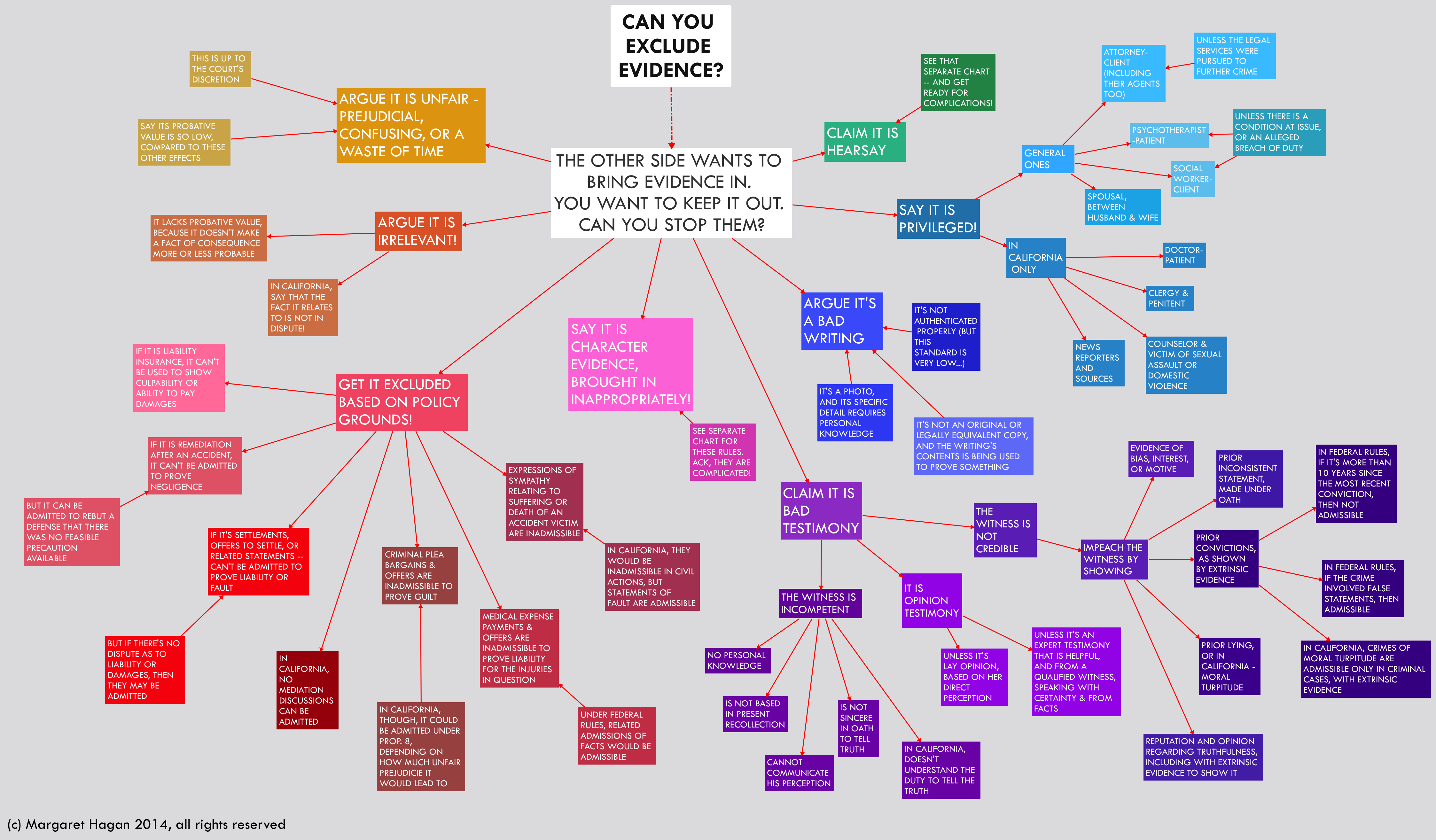

In order to introduce documentary and electronic evidence obtained in compliance with California Electronic Communication Privacy Act (Penal Code §§ 1546.1 and 1546. 2) in court, it must have four components:

- it must be relevant.

- it must be authenticated.

- its contents must not be inadmissible hearsay; and

- it must withstand a “best evidence” objection.

If the digital evidence contains “metadata” (data about the data such as when the document was created or last accessed, or when and where a photo was taken) proponents will to need to address the metadata separately, and prepare an additional foundation for it.

Relevance of Evidence

Only relevant evidence is admissible. (Evid. Code, § 350.) To be “relevant,” evidence must have a tendency to prove or disprove any disputed fact, including credibility. (Evid. Code, § 210.) All relevant evidence is admissible, except as provided by statute. (Evid. Code, § 351.)

For digital evidence to be relevant, the defendant typically must be tied to the evidence, usually as the sender or receiver. With a text message, for example, the proponent must tie the defendant to either the phone number that sent, or the phone number that received, the text. If the defendant did not send or receive/read the text, the text-as-evidence might lack relevance, one must prove that the device used was in the hands of the person being accused. In addition; evidence that the defendant is tied to the number can be circumstantial. And evidence that the defendant received and read a text also can be circumstantial.

Theories of admissibility include:

- Direct evidence of a crime

- Circumstantial evidence of a crime

- Identity of perpetrator

- Intent of perpetrator

- Motive

- Credibility of witnesses

- Impeachment

- Negates or forecloses a defense

- Basis of expert opinion

- Lack of mistake

Under Evidence Code 352 EC, even if the evidence is relevant and admissible, a judge may exclude it if they believe it would be confusing or misleading or if its admission could unfairly prejudice the jury against the defendant.

Introducing Documentary and Electronic Evidence

Authentication of Evidence

To “authenticate” evidence, you must introduce sufficient evidence to sustain a finding that the writing is what you say it is. (Evid. Code, § 1400 (a).) You need not prove the genuineness of the evidence, but to authenticate it, you must have a witness lay basic foundations for it. In most cases you do this by showing the writing to the witness and asking, “what is this?” and “how do you know that?” It is important to note that the originator of the document is not required to testify.

(Evid. Code, § 1411.) The proponent should present evidence of as many of the grounds below as possible. However, no one basis is required. Additionally, authentication does not involve the truth of the document’s content, rather only whether the document is what it is claimed to be.

(City of Vista v. Sutro & Co. (1997) 52 Cal.App.4th 401, 411-412.) Digital evidence does not require a greater showing of admissibility merely because, in theory, it can be manipulated. Conflicting inferences go to the weight not the admissibility of the evidence.

(People v. Goldsmith (2014) 59 Cal. App.258, 267) In Re KB (2015) 238 Cal.App.4th 989, 291-292 [upholding red light camera evidence].)

Goldsmith superseded People v. Beckley (2010) 185 Cal. App.4th 509, which required the proponent to produce evidence from the person who took a digital photo or expert testimony to prove authentication. Documents and data printed from a computer are considered to be an “original.” (Evid. Code 255.) Printouts of digital data are presumed to be accurate representation of the data.

(Evid Code §§ 1552, 1553.) However, that resumption can be overcome by evidence presented by the opposing party. If that happens, the proponent must present evidence showing that by a preponderance, the printouts are accurate and reliable.

(People v. Retke (2015), 232 Cal. App. 4th 1237 [successfully challenging red light camera data].)

A. You can authenticate documents by:

- Calling a witness who saw the document prepared. (Evid. Code, § 1413.)

- Introducing an expert handwriting comparison. (Evid. Code, § 1415.)

- Asking a lay witness who is familiar with the writer’s handwriting to identify the handwriting. (Evid. Code, § 1516.)

- Asking the finder of fact (i.e. the jury) to compare the handwriting on the document to a known exemplar. (Evid. Code, § 1470.)

- Showing that the writing refers to matters that only the writer would have been aware. (Evid. Code, § 1421.)

- Using various presumptions to authenticate official records with an official seal or signature. (Evid. Code, § 1450-1454.) Official records would include state prison records, Department of Motor Vehicle documents or documents filed with the Secretary of State. There is a presumption that official signatures are genuine. (Evid. Code, § 1530, 1453.)

- Any other way that will sustain a finding that the writing is what you say it is. The Evidence Code specifically does not limit the means by which a writing may be authenticated and proved. (Evid. Code, § 1410; See also People v. Olguin (1994) 31 Cal.App.4th 1355, 1372-1373 [rap lyrics authenticated in gang case even though method of authentication not listed in Evidence Code].)SECTION 1401.

(a) Authentication of a writing is required before it may be received in evidence.(b) Authentication of a writing is required before secondary evidence of its content may be received in evidence.

B. Common ways to authenticate email include:

- Chain of custody following the route of the message, coupled with testimony that the alleged sender had primary access to the computer where the message originated.

- Security measures such as password-protections for showing control of the account. (See generally, People v. Valdez (2011) 201 Cal.App.4th 1429.)

- The content of the email writing refers to matters that only the writer would have been aware.

- Recipient used the reply function to respond to the email; the new message may include the sender’s original message.

- After receipt of the email, the sender takes action consistent with the content of the email.

- Comparison of the e-mail with other known samples, such as other admitted e-mails.

- E-mails obtained from a phone, tablet or computer taken directly from the sender/receiver, or in the sender/receiver’s possession.

In the majority of cases a variety of circumstantial evidence establishes the authorship and authenticity of a computer record. For further information, please consult Chapter 5 – Evidence of the United States Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section Criminal Division, Searching and Seizing Computers and Obtaining Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations (2009) . See also, Lorraine v. Markel American Ins. Co. (D. Md. 2007) 241F.R.D. 534, 546 [seminal case law on authenticating digital evidence under F.R.E.].)

C. Common ways to authenticate chat room or Internet relay chat (IRC) communication include:

- Evidence that the sender used the screen name when participating in a chat room discussion.

- For example, evidence obtained from the Internet Service Provider that the screen name, and/or associated internet protocol (IP address) is assigned to the defendant or evidence circumstantially tying the defendant to a screen name or IP address.

- Security measures such as password-protections for showing control of the account of the sender and excluding others from being able to use the account. (See generally, People v. Valdez (2011) 201 Cal.App.4th 1429.)

- The sender takes action consistent with the content of the communication.

- The content of the communication identifies the sender or refers to matters that only the writer would have been aware

- The alleged sender possesses information given to the user of the screen name (contact information or other communications given to the user of the screen name).

- Evidence discovered on the alleged sender’s computer reflects that the user of the computer used the screen name. (See U.S. v. Tank (9th Cir. 2000) 200 F.3d 627.)

- Defendant testified that he owned account on which search warrant had been executed, that he had conversed with several victims online, and that he owned cellphone containing photographs of victims, personal information that defendant confirmed on stand was consistent with personal details interspersed throughout online conversations, and third-party service provider (Facebook) provided certificate attesting to chat logs’ maintenance by its automated system. (U.S. v. Browne (3d Cir. Aug.25, 2016) 2016 WL 4473226, at 6.)

In the majority of cases it is a variety of circumstantial evidence that provides the key to establishing the authorship and authenticity of a computer record. For further information, please consult Chapter 5 – Evidence of the United States Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section Criminal Division, Searching and Seizing Computers and Obtaining Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations (2009)

D. Common ways to authenticate social media postings include:

- Testimony from a witness, including a police officer, with training and experience regarding the specific social media outlet used testified about what s/he observed. (In re K.B. (2015) 238 Cal.App.4th 989.) What is on the website or app, at the time the witness views it, should be preserved in a form that can be presented in court.

- Evidence of social media postings obtained from a phone, tablet or computer taken directly from the sender/receiver, or in the sender/receiver’s possession.

- Testimony from the person who posted the message.

- Chain of custody following the route of the message or post, coupled with testimony that the alleged sender had primary access to the computer where the message originated.

- The content of the post refers to matters that only the writer would have been aware, publicly broadcasted writings (web post that anyone can copy and paste would not fall under this).

- After the post on social media, the writer takes action consistent with the content of the post.

- The content of the post displays an image of the writer. (People v. Valdez (2011) 201 Cal.App.4th 1429.)

- Other circumstantial evidence including that the observed posted images were later recovered from suspect’s cell phone and the suspect was wearing the same clothes and was in thesame location that was depicted in the images. (In re K.B. (2015) 238 Cal.App.4th 989.)

- Security measures for the social media site such as passwords-protections for posting and deleting content suggest the owner of the page controls the posted material. (People v. Valdez (2011) 201 Cal.App.4th 1429.)

In the majority of cases it is a variety of circumstantial evidence that provides the key to establishing the authorship and authenticity of a computer record. “Mutually reinforcing content” as well as “pervasive consistency of the content of the page” can assist in authenticating photographs and writings. (People v. Valdez (2011) 201 Cal.App.4th 1429, 1436.) For further information, please consult Chapter 5 – Evidence of the United States Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section Criminal Division, Searching and Seizing Computers and Obtaining Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations (2009) For examples of sufficient circumstantial evidence authenticated social media posts see, Tienda v. State (Tex. Crim. App. 2012) 358 S.W.3d 633, 642; Parker v. State (Del. 2014) 85 A.3d 682, 687. Contrast, Griffin v. State (2011) 419 Md. 343, 356–359.

E. Common ways to authenticate web sites include:

- Testimony from a witness, including a police officer about what s/he observed. (See In re K.B. (2015) 238 Cal.App.4th 989.) What is on the website or app, at the time the witness views it, should be preserved in a form that can be presented in court.

- Testimony from the person who created the site.

- Website ownership/registration. This is a legal contract between the registering authority (e.g.

Network Solutions, PDR Ltd, D/B/A PublicDomainRegistry.com, etc.) and the website owner, allowing the registered owner to have total dominion and control of the use of a website name (domain) and its content. (See People v. Valdez (2011) 201 Cal.App.4th 1429 [password protection suggest the owner of the page controls the posted material].) It may be possible to admit archived versions of web site content, stored and available at a third party web site (See https://archive.org/web/ [Wayback Machine].) First, it may be authenticated by a percipient witness who previously saw or used the site. It may also be possible to obtain a declaration or witness to testify to the archive. (See e.g. Telewizja Polska USA, Inc. v. Echostar Satellite Corp., 2004 WL 2367740, at 16 (N.D.Ill. Oct.15, 2004) [analyzing admissibility of the content of an achieved website].) The underlying challenge for web sites in not the authentication of the site; rather the content or hearsay material contained therein.

In St. Clair v. Johnny’s Oyster & Shrimp, Inc. (S.D.Tex.1999) 76 F.Supp.2d 773, 774-75 the court noted that “voodoo information taken from the Internet” was insufficient to withstand motion to dismiss because “[n]o web-site is monitored for accuracy” and “this so-called Web provides no way of verifying the authenticity” of information plaintiff wished to rely on. (See also Badasa v. Mukasey (8th Cir. 2008) 540 F.3d 909 [Nature of Wikipedia makes information from the website unreliable].) However, at noted in Section III Hearsay, the contents of the web site could be admitted as an operative fact or under a number of exceptions including an admission of a party opponent.

F. Authenticating Texts:

A text message is a writing within the meaning of Evidence Code section 250, which may not be admitted in evidence without being authenticated. (Stockinger v. Feather River Community College (2003) 111 Cal.App.4th 1014, 1027–1028.)

A text message may be authenticated “by evidence that the writing refers to or states matters that are unlikely to be known to anyone other than the person who is claimed by the proponent of the evidence to be the author of the writing” (Evid.Code, § 1421), or by any other circumstantial proof of authenticity (Id., § 1410).

As of August 2016, there are no published California cases that specifically discuss what is required for authenticating a text message. Unpublished California opinions are consistent with the rule set forth above for authenticating e-mails and chats through a combination of direct and circumstantial evidence based on the facts of the case. Because of the mobile nature of smart phones, the proponent must take care to tie the declarant to the phone from which texts were seized or to the phone number listed in records obtained from the phone company. Often this done through cell phone records or the phone being seized from the defendant, his home or car or other witnesses testifying that this was how they communicated with the defendant.

Published opinions from other jurisdictions and unpublished opinions from California provide some guidance:

Published opinions from other jurisdictions and unpublished opinions from California provide some guidance:

- (People v. Lugashi (1988) 205 Cal.App.3d 632, 642.) As Lugashi explains, although mistakes can occur, “ ‘such matters may be developed on cross-examination and should not affect the admissibility of the [record] itself.’ (People v. Martinez (2000) 22 Cal.4th 106, 132.)

- Victim testified he knew the number from which text was sent because Defendant told him the number. The contents of the texts referred to victim as a snitch. The defendant called the victim during the course of the text message conversation. [(Butler v. State, 459 S.W. 3d 595 (Crim. Ct App. Tx. April 22, 2015].)

- Testimony of records custodian from telecommunications company, explaining how company kept records of actual content of text messages, the date and time text messages were sent or received, and the phone number of the individuals who sent or

- received the messages, provided proper foundation for, and sufficiently authenticated, text messages admitted into evidence in trial on armed robbery charges. (Fed.Rules Evid.Rule 901(a), U.S. v. Carr (11th Cir. 2015) 607 Fed.Appx. 869.)

- Ten of 12 text messages sent to victim’s boyfriend from victim’s cellular telephone following sexual assault were not properly authenticated to extent that State’s evidence did not demonstrate that defendant was author of text messages. (Rodriguez v. State (2012) 128 Nev. Adv. Op. 14, [273 P.3d 845].)

- Murder victim’s cell phone recovered from scene of crime. Forensic tools used on phone recovered texts back and forth between victim and defendant. (People v. Lehmann (Cal. Ct. App., Sept. 17, 2014, No. G047629) 2014 WL 4634272 [Unpublished].)

- Defendant laid an inadequate foundation of authenticity to admit, in prosecution for assault with a deadly weapon, hard copy of e‑mail messages (Instant Messages) between one of his friends and the victim’s companion, as there was no direct proof connecting victim’s companion to the screen name on the e‑mail messages. (People v. Von Gunten (2002 Cal.App.3d Dist.) 2002 WL 501612. [Unpublished].)

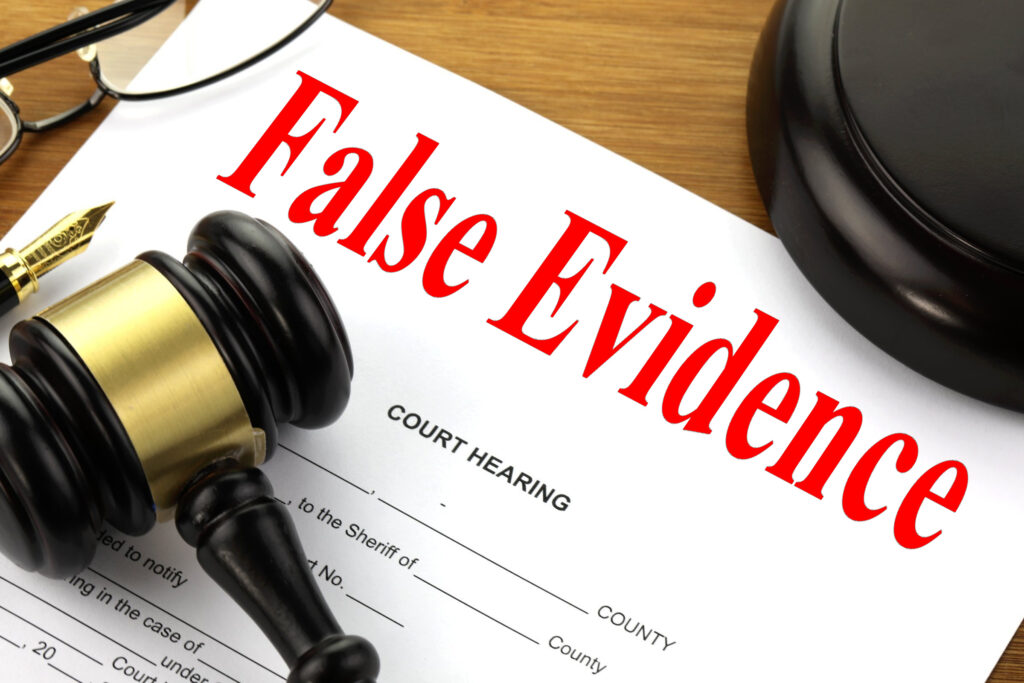

- “knowingly allowing a witness to testify falsely.” (People v. Pike (1962) 58 Cal.2d 70, 97, [22 Cal. Rptr. 664, 372 P.2d 656].) The inquirer asks us to assume that disclosure of the perjured testimony to the court would so adversely reflect on the client’s credibility that the court could “reasonably be expected to render an adverse decision.“

ATTORNEY’S DUTY TO THE COURT

For the attorney to proceed with trial without taking further action raises the question whether the attorney has implicitly but intentionally consented to a deception upon the court. (Bus. & Prof. Code, 6128.) It also raises the question whether the attorney s silence and inaction is “consistent with truth” or an attempt to “mislead the judge… by an artifice of false statement of [material] fact.” (Bus. & Prof. Code, 6068, subd. (d).)

Active misrepresentations by an attorney to opposing counsel by deliberately failing to state a material fact “falls short of the honesty and integrity required of an attorney at law in the performance of his professional duties.” (Coviello v. State Bar (1955) 45 Cal.2d 57, 65-66 [286 P.2d 357].) An attorney’s active representations to a judge, accompanied by deliberate failure to disclose a material fact, is similarly reprehensible. But, in this case, the attorney is faced with decisions about how to proceed immediately after his/her discovery of the perjured testimony. The attorney has not yet taken the step of making any further representations while deliberately concealing the perjury.

It is our opinion, under the circumstances of this case, that the attorney may not remain silent and is required to take action to ensure that he/she does not give his/her implicit consent to the deception. Silence and inaction would not be consistent with truth and would constitute, albeit indirectly, an attempt to mislead the judge by an artifice, to wit, the client’s false testimony of a material fact. “An attorney who attempts to benefit his/her client through the use of perjured testimony may be subject to criminal prosecution (Pen. Code, 127) as well as severe disciplinary action.” (In re Jones (1930) 208 Cal. 240, 242 [280 P.2d 964].) (In re Branch (1969) 70 Cal.2d 200, 210-211, [74 Cal. Rptr. 238, 449 P.2d 174].) But the attorney must speak and act consistently with his/her duties to his/her client.

Opinions of the American Bar Association are not precedential guides for professional conduct of members of the California bar. (CAL 1983-71.) But they are helpful in suggesting alternative courses of conduct. ABA Formal Opinion 287 (June 27, 1953) considered the case of an attorney who secured a divorce for a client who later informed the attorney that he/she had committed perjury in a deposition in securing the divorce. The opinion held that the attorney was precluded from revealing the perjury to the court, but that the attorney should “urge his client to make the disclosure [to the court]” and if he/she refuses to do so “should have nothing further to do with him” but the attorney “should not disclose the facts to the court.” As we note below, this conclusion neglects to consider the implications of persuading the client to make disclosure to the court. It is also inapposite because it does not involve perjury committed and known to the attorney in the midst of trial. But it does suggest that withdrawal of representation by the attorney may be an appropriate course of conduct.

The Bar Association of San Francisco Legal Ethics Committee has considered the duties of an attorney whose client refused to disclose the existence of community assets during the course of a domestic relations matter. (SF Opinion 1977-2.) The Committee opined:

“In most cases the client’s refusal to disclose the existence of community assets constitutes fraud. However, since the client usually discloses this information in confidence, the attorney is under conflicting duties to maintain the confidentiality of his client’s communication and, on the other hand not to suppress the fraud or maintain his deliberate silence. Therefore, the attorney should withdraw from his representation of the client, and his failure to withdraw is a proper subject for disciplinary proceedings.”

But this opinion did not address the question of an attorney’s obligation to withdraw in the midst of trial. The domestic relations matter had not yet reached the trial stage so that, as a practical matter, withdrawal of representation would not severely prejudice the client. In the instant case, the inquirer has stated, and we accept as true, that withdrawal would result in the client’s losing his/her case.

But the attorney may have a duty to withdraw from the case. Rule 2-111(B)(2), Rules of Professional Conduct mandates that he/she withdraw when:

“He knows or should know that his continued employment will result in a violation of these Rules of Professional Conduct [which includes Rule 7-105] or of the other State Bar Act [which includes Bus. & Prof. Code, 6068, 6128].” source

Rule 3.3: Candor toward the tribunal

Rule 3.3(a)(1)] provides that a lawyer shall not knowingly “make a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal or fail to correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made to the tribunal by the lawyer.”

Rule 3.3(a)(3) (if lawyer has knowledge of client or client-witness perjury, the duty to take remedial measures includes, “if necessary, disclosure to the tribunal.”)

The key to prevent criminal and civil negligence is to withdraw without disclosing the perjured testimony an attorney may remove themselves from a case or request dismissal of his cause of actions once he realizes the perjury. People v. Brown (1988) 203 Cal.App.3d 1335, 1339- 1340, fn. 1 [250 Cal.Rptr. 762]. See also, Cal. State Bar Formal Opn. No. 2015-192 (attorneys may disclose to the court only as much as reasonably necessary to demonstrate the need to withdraw and without violating the duty of confidentiality)

Attorney’s statutory duties of candor are found in Business and Professions Code sections 6068(b) and (d), 6106 and 6128(a) discussed in scenario #2. Attorney’s ethical duty of candor is found in rule 3.3(a)(3). Given Attorney’s knowledge that Witness has given materially false testimony, this rule requires Attorney to “take reasonable remedial measures, including, if necessary, disclosure to the tribunal unless disclosure is prohibited by Business and Professions Code section 6068, subdivision (e) and rule 1.6.”

An attorney violates the duty of candor, even where the fabrications are the work of another, if the attorney, after learning of their falsity, continues to assert their authenticity. In the Matter of Temkin (Review Dept. 1991) 1 Cal. State Bar Ct. Rptr. 321; Olguin v. State Bar (1980) 28 Cal.3d 195, 198-200 [167 Cal.Rptr. 876].

Rule 3.4 Fairness to Opposing Party and Counsel (g) in trial, assert personal knowledge of facts in issue except when testifying as a witness, or state a subjective opinion as to the guilt or innocence of an accused

Rule 4.1 Truthfulness in Statements to Others In the course of representing a client a lawyer shall not knowingly:* (a) make a false statement of material fact or law to a third person;*

Rule 8.4 outlines what constitutes professional misconduct

Rule 9.4 states “In addition to the language required by Business and Professions Code section 6067, the oath to be taken by every person on admission to practice law is to conclude with the following: ‘As an officer of the court, I will strive to conduct myself at all times with dignity, courtesy, and integrity.’ ”

yes, you can sue your lawyer for lying. Direct lying to the courts that would lead to harm or have harmed equate to malpractice.

Penal Code 118 PC – Perjury is defined as testimony under oath which is “willfully” false on a “material” matter. California Penal Code section 118. “Materiality” means a false statement that “could probably influence the outcome of the proceeding.”

People v. Rubio (2004) 121 Cal.App.4th 927, 933 [17 Cal.Rptr.3d 524].

California Penal Code 126 states that perjury is punishable by imprisonment for two, three, or four years under subdivision (h) of Section 1170. This section is part of Chapter 5, which is about perjury and subornation of perjury

Perjury is defined in California Penal Code section 118: “Every person who, having taken an oath that he will testify… truly before any competent [court]… wilfully and contrary to such oath, states as true any material matter which he knows to be false… is guilty of perjury.”

Perjury is a felony. (Pen. Code, 126.) The perjurer’s lack of knowledge of materiality is no defense to the crime. (Pen. Code, 123.)

The first duty arises under Business and Professions Code section 6068, subdivision (e) which provides that it is the duty of a lawyer:

“To maintain inviolate the confidence and at every peril to himself to preserve the secrets, of his client.”

The second duty arises under Business and Professions Code section 6128 which provides that an attorney is guilty of a crime who:

“(a) Is guilty of any deceit or collusion, or consents to any deceit or collusion, with intent to deceive the court or any party.“

This second duty is also reflected in other provisions of the Business and Professions Code and Rules of Professional Conduct.

“It is the duty of an attorney to… maintain the respect due to the courts of justice and judicial officers.” (Bus. & Prof. Code, 6068, subd. (b).)

“It is the duty of an attorney to… employ, for the purpose of maintaining the causes confided to him, such means only as are consistent with truth, and never to seek to mislead the judge or any judicial officer by an artifice or false statement of law or fact.” (Bus. & Prof. Code, 6068, subd. (d).) (See also Rule of Professional Conduct 7-105 [which restates in pertinent part Bus. & Prof. Code, 6068, subd. (d)].)

This scenario concerns an attorney’s duty of candor to the court, found in rule 3.3 (“Candor Toward the Tribunal.”) and Business and Professions Code section 6068. The former provides, in part, “A lawyer shall not: . . . offer evidence the lawyer knows to be false.”

Business and Professions Code section 6068(b) and (d) likewise provides, “It is the duty of an attorney . . . (b) To maintain the respect due to the courts of justice and judicial officers. . . . [and] (d) To employ . . . means only as are consistent with truth, and never to seek to mislead the judge or any judicial officer by an artifice or false statement of fact or law.”

Correspondingly, Business and Professions Code section 6106 proscribes “the commission of any act involving, moral turpitude, dishonesty or corruption.” In addition, Business and Professions Code section 6128(a) provides: “Every attorney is guilty of a misdemeanor who

either: (a) Is guilty of any deceit or collusion, or consents to any deceit or collusion, with intent to deceive the court or any party.” It is well-established in case law, as well, that “[a]n attorney who attempts to benefit his client through the use of perjured testimony may be subject to criminal prosecution … as well as severe disciplinary action.” In re Branch (1969) 70 Cal.2d 200, 211 [74 Cal.Rptr. 238].

BPP Code § 6068(d) provides it is the duty of an attorney: (d) To employ, for the purpose of maintaining the causes confided to him or her those means only as are consistent with truth, and never to seek to mislead the judge or any judicial officer by an artifice or false statement of fact or law.

A fair and impartial trial is a fundamental aspect of the right of accused persons not to be deprived of liberty without due process of law. (U.S. Const., 5th & 14th Amends.; Cal. Const., art. I, § 7, subd. (a); see, e.g., Tumey v. Ohio (1927) 273 U.S. 510 [71 L. Ed. 749, 47 S. Ct. 437, 50 A.L.R. 1243]; In re Murchison (1955) 349 U.S. 133, 136 [99 L. Ed. 942, 946, 75 S. Ct. 623]; People v. Lyons (1956) 47 Cal. 2d 311, 319 [303 P.2d 329]; In re Winchester (1960) 53 Cal. 2d 528, 531 [2 Cal. Rptr. 296, 348 P.2d 904].)

People v. Lyons, supra, 47 Cal.2d at p. 318; People v. Talle (1952) 111 Cal. App. 2d 650, 676-678 [245 P.2d 633].) Nor is the role of the prosecutor in this regard simply a specialized version of the duty of any attorney not to overstep the bounds of permissible advocacy.

“[I]n both civil and criminal matters, a party’s attorney has general authority to control the procedural aspects of the litigation and, indeed, to bind the client in these matters.” In re Horton (1991) 54 Cal.3d 82, 95, 102 [284 Cal.Rptr. 305]. Encompassed in this is the authority to control matters of ordinary trial strategy, such as which witnesses to call, the manner of cross-examination, what evidence to introduce, and whether to object to an opponent’s evidence. Gdowski v. Gdowski (2009) 175 Cal.App.4th 128, 138 [95 Cal.Rptr.3d 799]. However, a decision on any matter that will affect the client’s substantive rights is within the client’s sole authority. Maddox v. City of Costa Mesa (2011) 193 Cal.App.4th 1098, 1105 [122 Cal.Rptr.3d 629]. In addition, if Witness’s only purpose at trial would be to testify as an alleged eyewitness on matters now known to be false, Witness should not be mentioned in pretrial disclosure documents (for example, pretrial witness lists or trial briefs).

Penal Code section 127: “Every person who willfully procures another person to commit perjury is guilty of subornation of perjury, and is punishable in the same manner as he would be if personally guilty of the perjury so procured.”

Rule 1.16(b) presents several circumstances allowing for permissive withdrawal that may be implicated under these facts: Client is seeking to pursue a course of conduct the lawyer reasonably believes was a crime or fraud, the client insists that the lawyer pursue a course of conduct that is criminal or fraudulent, the client’s conduct renders it unreasonably difficult for the lawyer to carry out the representation effectively or the representation likely will result in a violation of the Rules of Professional Conduct or the State Bar Act. Rule 1.16(b)(2)-(4) and (b)(9).

The United States Supreme Court has repeatedly held that the right to testify does not include a right to commit perjury. Nix v. Whiteside, 475 U.S. 157, 173 (1986); United States v. Havens, 446 U.S 620, 626 (1980).

Id. at Rule 3.3. Similarly, the ABA’s Model Code of Professional Responsibility states, “In his representation of a client, a lawyer shall not . .. [k]nowingly use perjured testimony or false evidence.” Id. at DR 7-102(A)(4).

The Proposed Evidentiary Standard: Actual Knowledge

Although an attorney clearly must not participate in the presentation of perjured testimony, on what basis can an attorney conclude that a defendant is going to testify falsely? No controlling precedent provides guidance on this critical issue.

Commentators and courts in other jurisdictions have set forth a variety of standards for determining when an attorney “knows” the client intends to testify falsely, including “good cause to believe” a client intends to testify falsely, State v. Hischke, 639 N.W.2d 6, 10 (lowa 2002); “compelling support” for concluding that the client will perjure himself, Sanborn v. State, 474 So.2d 309, 313 n.2 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1985); “knowledge beyond a reasonable doubt,” Shockley v. State, 565 A.2d 1373, 1379 (Del. 1989); “a firm factual basis,” United States ex rel. Wilcox v. Johnson, 555 F.2d 115, 122 (3d Cir.1977); “a good faith determination,” People v. Bartee, 566 N.E.2d 855, 857 (ILI. Ct. App. 1991), and “actual knowledge,” United States v. Del Carpio-Cotrina, 733 F.Supp. 95, 99 (S.D.Fla. 1990). See generally, Commonwealth v. Mitchell, 781 N.E.2d 1237, 1246-47 (Mass.) (surveying the range of standards), cert. denied, 123 S.Ct. 2253 (2003).

This Opinion adopts the most stringent standard: “before defense attorneys can refuse to assist a client in testifying, they must know that the client will testify falsely based on the client’s

‘The Code of Professional Responsibility and Rules of Professional Conduct. The older Model Code of Professional Responsibility

Rules of Professional Conduct was adopted in 1983 (and recently amended in other areas. See Silver, Iruth. Mistice, and the American Way:

The Case Against the Client Perjury Rules, 47 Vand. L. Rev. 339, 343-50 (1994) (tracing the development of the Model Code of Professional Responsibility and the Model Rules of Professional Conduct). Other than California, all states have substantially adopted either the Code of Professional Responsibility or the Rules of Professional Conduct.

Filing Frivolous Lawsuits

Filing lawsuits without a reasonable basis. Connecticut judges do not like people filing frivolous lawsuits to harass people. Instead, lawyers must perform a reasonable investigation to determine whether valid grounds exist for filing a lawsuit. Obviously, a lawyer cannot uncover all evidence before filing, but they cannot file an obviously meritless case. If they do, their client could be sued for vexatious litigation.

sometimes lawyers lie to make you the Vexatious Litigant, there are rules for that too Malicious Use of Vexatious Litigant – Vexatious Litigant Order Reversed

California Supreme Court Confirms that the “anti-SLAPP” Statute Applies to Claims of Discrimination and Retaliation

G. Authenticating Metadata:

Another way in which electronic evidence may be authenticated is by examining the metadata for the evidence. Metadata, “commonly described as ‘data about data,’ is defined as ‘information describing the history, tracking, or management of an electronic document.’ Metadata is ‘information about a particular data set which describes how, when and by whom it was collected, created, accessed, or modified and how it is formatted (including data demographics such as size, location, storage requirements and media information).’ Some examples of metadata for electronic documents include:

a file’s name, a file’s location (e.g., directory structure or pathname), file format or file type, file size, file dates (e.g., creation date, date of last data modification, date of last data access, and date of last metadata modification), and file permissions (e.g., who can read the data, who can write to it, who can run it). Some metadata, such as file dates and sizes, can easily be seen by users; other metadata can be hidden or embedded and unavailable to computer users who are not technically adept.” Because metadata shows the date, time and identity of the creator of an electronic record, as well as all changes made to it, metadata is a distinctive characteristic of all electronic evidence that can be used to authenticate it under Federal Rule 901(b)(4).

Although specific source code markers that constitute metadata can provide a useful method of authenticating electronically stored evidence, this method is not foolproof because, “[a]n unauthorized person may be able to obtain access to an unattended computer. Moreover, a document or database located on a networked-computer system can be viewed by persons on the network who may modify it. In addition, many network computer systems usually provide authorization for selected network administrators to override an individual password identification number to gain access when necessary. Metadata markers can reflect that a document was modified when in fact it simply was saved to a different location. Despite its lack of conclusiveness, however, metadata certainly is a useful tool for authenticating electronic records by use of distinctive characteristics.” (Lorraine v. Markel American Ins. Co. (D. Md. 2007) 241 F.R.D. 534, 547–48 [citations omitted].)

H. Challenges to Authenticity

Challenges to the authenticity of computer records often take on one of three forms. First, parties may challenge the authenticity of both computer-generated and computer-stored records by questioning whether the records were altered, manipulated, or damaged after they were created.

Second, parties may question the authenticity of computer-generated records by challenging the reliability of the computer program that generated the records. California state courts have refused to require, as a prerequisite to admission of computer records, testimony on the “acceptability, accuracy, maintenance, and reliability of … computer hardware and software.” (People v. Lugashi (1988) 205 Cal.App.3d 632, 642.) As Lugashi explains, although mistakes can occur, “ ‘such matters may be developed on cross-examination and should not affect the admissibility of the [record] itself.’ (People v. Martinez (2000) 22 Cal.4th 106, 132.)

Third, parties may challenge the authenticity of computer-stored records by questioning the identity of their author. For further information, please consult “Defeating Spurious Objections to Electronic Evidence,” by Frank Dudley Berry, Jr., [click here] or Chapter 5 – Evidence of the United States Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section Criminal Division, Searching and Seizing Computers and Obtaining Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations (2009)

I. Hearsay Rule

The first question to ask is whether or not the information within the document is hearsay. If it is hearsay, then you need an applicable exception, such as business and government records or statement by party opponent. Examples of things that are not hearsay include;

- operative facts and

- data that is generated by a mechanized process and not a human declarant and,

- A statement being used to show its falsity not its truth.

J. Operative Facts

Where “ ‘the very fact in controversy is whether certain things were said or done and not … whether these things were true or false, … in these cases the words or acts are admissible not as hearsay[,] but as original evidence.’ ” (1 Witkin, Cal. Evidence (4th ed. 2000) Hearsay, § 31, p. 714.) For example, in an identity theft prosecution, there will be no hearsay issue for the majority of your documents. The documents are not being offered for the truth of the matter asserted; they are operative facts. In Remington Investments, Inc v. Hamedani (1997) 55 Cal.App.4th 1033, the court distinguished between the concept of authentication and hearsay. The issue was whether a promissory note was admissible. The court observed that: ‘The Promissory Note document itself is not a business record as that term is used in the law of hearsay, but rather an operative contractual document admissible merely upon adequate evidence of authenticity. (Id. At 1043.)

Under Remington, promissory notes, checks and other contracts are not hearsay, but operative facts. Moreover, forged checks, false applications for credit, and forged documents are not hearsay. They are not being introduced because they are true. They are being introduced because they are false. Since they are not being introduced for the truth of the matter asserted there is no hearsay issue.

Other examples of non-hearsay documents would include:

- The words forming an agreement are not hearsay (Jazayeri v. Mao (2009) 174 Cal.App.4th

- 301, 316 as cited by People v. Mota (Cal. Ct. App., Oct. 8, 2015, No. B252938) 2015 WL 5883710 (Unpublished)

- A deposit slip and victim’s identification in a burglary case introduced to circumstantially

- connect the defendant to the crime. (In re Richard (1979) 91 Cal.App.3d 960, 971-979.)

- Pay and owes in a drug case. (People v. Harvey (1991) 233 Cal.App.3d 1206, 1222-1226.)

- Items in a search to circumstantially connect the defendant to the location. (People v. Williams (1992) 3 Cal.App.4th 1535, 1540-1543.)

- Invoices, bills, and receipts are generally hearsay unless they are introduced for the purpose of corroborating the victim’s damages. (Jones v. Dumrichob (1998) 63 Cal.App.4th 1258, 1267.)

- Defendant’s social media page as circumstantial evidence of gang involvement. (People v. Valdez (2011) 201 Cal.App.4th 1429.

- Logs of chat that was attributable to Defendant were properly admitted as admissions by party opponent, and the portions of the transcripts attributable to another person were properly classified as “non hearsay”, as they were not “offered for the truth of the matter asserted.” Replacing screen names with actual names appropriate demonstrative evidence. (U.S. v. Burt (7th Cir., 2007) 495 F.3d 733.)

- “To the extent these images and text are being introduced to show the images and text found on the websites, they are not statements at all—and thus fall outside the ambit of the hearsay rule.” (Perfect 10, Inc. v. Cybernet Ventures, Inc. (C.D.Cal.2002) 213 F.Supp.2d 1146, 1155.)

- Generally, photographs, video, and instrument read outs are not statements of a person as defined by the Evidence Code. (Evid.Code §§ 175, 225; People v. Goldsmith (2014) 59 Cal.4th 258, 274; People v. Lopez (2012) 55 Cal.4th 569, 583.)

Although the check itself is not hearsay, the bank’s notations placed on the back of the check showing that it was cashed is hearsay. The bank’s notations would be introduced for the truth of the matter asserted – that the check was cashed. Evidence Code sections 1270 and 1271 solve this problem by allowing the admission of these notations as a business record.

Two helpful rules that apply to business records. First, it may be permissible to infer the elements of the business record exception. In People v. Dorsey (1974) 43 Cal.App.3d 953, the court was willing to find that it was common knowledge that bank statements on checking accounts are prepared daily on the basis of deposits received, checks written and service charges made even though the witness failed to testify as to the mode and time of preparation of bank statements. The second rule is that “lack of foundation” is not a sufficient objection to a business record. The defense must specify which element of the business record exception is lacking. (People v. Fowzer (1954) 127 Cal.App.2d 742.)

K. Computer Records Generated by a Mechanized Process

The first rule is that a printout of the results of the computer’s internal operations is not hearsay evidence because hearsay requires a human declarant. (Evid.Code §§ 175, 225.)

The Evidence Code does not contemplate that a machine can make a statement. (People v. Goldsmith (2014) 59 Cal.4th at 258, 274 [rejecting hearsay claims related to red light cameras];

People v. Hawkins (2002) 98 Cal.App.4th 1428; People v. Lopez (2012) 55 Cal. 4th.569). These log files are computer-generated records that do not involve the same risk of observation or recall as human declarants. Thus, email header information and log files associated with an email’s movement through the Internet are not hearsay. The usual analogy is that the clock on the wall and a dog barking are not hearsay. An excellent discussion on this issue can be found in Chapter 5 – Evidence of the United States Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section Criminal Division, Searching and Seizing Computers and Obtaining Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations (2009)

Metadata such as date/time stamps are not hearsay nor do they violate the confrontation clause because they are not testimonial. (See, People v. Goldsmith 59 Cal.4th at 258, 274-275; People v. Lopez (2012) 55 Cal. 4th.569, 583.)

L. Business Records

Log files and other computer-generated records from Internet Service Providers may also easily qualify under the business records exception to the hearsay rule. (Evid.Code §§1270, 1271, 1560, 1561.) Remember, you do not need to show the reliability of the hardware or software. (People v. Lugashi (1988) 205 Cal.App.3d 632.) Nor does the custodian of records need to completely understand the computer. (Id.) Additionally, the printout (as opposed to the entry) need not be made “at or near the time of the event.” (Aguimatang v. California State Lottery (1991) 234 Cal.App.3d 769.) Finally, a cautionary note from the Appellate Court in People v. Hawkins (2002) 98 Cal.App.4th 1428: “the true test for admissibility of a printout reflecting a computer’s internal operations is not whether the printout was made in the regular course of business, but whether the computer was operating properly at the time of the printout.” If the computer is used merely to store, analyze, or summarize material that is hearsay in nature, it will not change its hearsay nature and you will need an applicable exception for introduction. Common exceptions for the contents of email include: statement of the party, adoptive admission, statement in furtherance of a conspiracy, declaration against interest, prior inconsistent statement, past recollection recorded, business record, writing as a record of the act, or state of mind. Note also that records obtained by search warrant, and accompanied by a complying custodian affidavit, are admissible as if they were subpoenaed into court (Evid. Code §§ 1560-1561, effective January 1, 2017) and records obtained from an Electronic Communication Service provider that is a foreign corporation, and are accompanied by a complying custodian affidavit, are currently admissible pursuant to Penal Code § 1524.2(b)(4). (See also Pen. Code § 1546.1(d)(3).)

M. Government Records

An official record is very similar to a business record, even if it is obtained from a government website. The chief difference is that it may be possible to introduce an official record without calling the custodian or another witness to authenticate it. (Evid. Code, § 1280; See Lorraine v. Markel American Ins. Co. (D. Md. 2007) 241 F.R.D. 534, 548–49; EEOC v. E.I dupont de Nemours & Co. (2004) 65 Fed. R. Evid. Serv. 706 [Printout from Census Bureau web site containing domain address from which image was printed and date on which it was printed was admissible in evidence].) The foundation can be established through other means such as judicial notice or presumptions. (People v. George (1994) 30 Cal.App.4th 262,274.)

N. Published Tabulations

Prosecutors are often plagued with how to introduce evidence that was found using Internet-based investigative tools. For example, if your investigator used the American Registry For Internet Numbers (ARIN) programs (WHOIS, RWhois or Routing Registry Information), how is this admissible without calling the creator of these Internet databases? Evidence Code Section 1340 allows an exception to the hearsay rule, which allows the introduction of published tabulations, lists, directories, or registers. The only requirement is that the evidence contained in the compilation is generally used and relied upon as accurate in the course of business. Note that not all data aggregation sites may have the proper characteristics for this exception. In People v. Franzen (2012) 210 Cal.App.4th 1193, 1209–13, the court found that a subscription based service did not possess the characteristics that would justify treating its contents as a published compilation for purposes of section 1340

O. Former Best Evidence Rule

Reminder: The Best Evidence Rule has been replaced in California with the Secondary Evidence

Rule. The Secondary Evidence Rule allows the admissibility of copies of an original document. (Evid. Code, § 1521.) They are not admissible, however, if “a genuine dispute exists concerning material terms of the writing and justice requires the exclusion,” or if admitting the evidence would be “unfair.” (Evid. Code, § 1521.) In a criminal action it is also necessary for the proponent of the evidence to make the original available for inspection at or before trial. (Evid. Code, § 1522.) For email or any electronic document, this is especially important, given the wealth of information contained in its electronic format, as opposed to its paper image. Of interest, Evidence Code Section 1522 requires that the “original” be made available for inspection. Evidence Code Section 255 defines an email “original” as any printout shown to reflect the data accurately. Thus, the protections offered by Evidence Code Section 1522 are stripped away by Evidence Code Section 255. This is where the protections of Evidence Code Section 1521 are invoked: “It’s unfair, your Honor, not be able to inspect the email in its original format.” Also, remember that Evidence Code Section 1552 states that the printed representation of computer information or a computer program is presumed to be an accurate representation of that information. Thus, a printout of information will not present any “best evidence rule” issues absent a showing that the information is inaccurate or unreliable. Oral testimony regarding the content of an email [writing] is still inadmissible absent an exception. (Evid. Code, § 1523.) Exceptions include where the original and all the copies of the document were accidentally destroyed. Of course, none of the above rules applies at a preliminary hearing. (See Pen. Code § 872.5 [permits otherwise admissible secondary evidence at the preliminary hearing]; B. Witkin, 2 California Evidence (3rd ed., 1986) § 932, p. 897 [“secondary evidence” includes both copies and oral testimony].) i This material was prepared by Robert M. Morgester, Senior Assistant Attorney General, California Department of Justice in 2003 for the High-Technology Crime: Email and Internet Chat Resource CD-ROM, and draws heavily upon Documentary Evidence Primer, by Hank M. Goldberg, Deputy District Attorney, Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office, January 1999. Material from that document was used with Mr. Goldberg’s permission. This material was updated in 2016 by Robert Morgester and Howard Wise, Senior Deputy District Attorney, Ventura County District Attorney’s Office.

P. How does Hearsay Play into the Era of Text Messaging?

With the ubiquitousness of smart phones, text messages have now become a preferred tool of communication for many. Due to the informal nature of text messages, many, if not most people fail to consider the potential evidentiary effect of a text message. As a general proposition, despite the informal usage of text messages, a text message can potentially still be evidence in the case, subject to the rules of hearsay, with further caveats. In this post, we specifically discuss how the lack of response to a text messages cannot qualify as an adoptive admission as an exception to the hearsay rule.

Q. Hearsay evidence in Trial

The concept of “hearsay” as it pertains to trial is well known. As many people know, out of court statements offered for its truth are barred by the hearsay rule due to inherent trustworthiness and reliability concerns. However, there are many exceptions to this rule that would allow an otherwise inadmissible statement to be offered as evidence or for some other purpose in court. One major exception to the hearsay rule are admissions made by a party.

ALSO READ Why a Lis Pendens is Important in Specific Performance Claims

R. Admissions Made by a Party

Specifically, an admission for the purposes of the hearsay exceptions in any out of court statement or assertive conduct by a party to the action that is inconsistent with a position the party is taking at current proceeding. The statement itself does not necessarily need to have been against the party’s interest when it was made. Indeed, even a statement self-serving whenmade may be admissible as a party admission if contrary to the party’s present position at trial. (People v. Richards (1976) 17 Cal.3d 614, 617-618 (disapproved on other grounds by People v. Carbajal (1995) 10 Cal.4th 1114, 1126.)

Notably, an admission does not necessarily require an affirmative statement by the party taking the inconsistent position. Indeed, silence may be treated as an adoptive admission if, under the circumstances, a reasonable person would speak out to clarify or correct the statement of another were it untrue. (People v. Riel (2000) 22 Cal.4th 1153, 1189.) However, silence is not admissible as an adoptive admission if another reasonable explanation can be demonstrated. Indeed, in the recent case of People v. McDaniel (2019) 38 Cal.App.5th 986, 999 (“McDaniel”), the Court of Appeal held that failure to respond to a text message accusing defendant of committing a crime was not admissible as an adoptive admission.

ALSO READ How to Win Attorneys’ Fees in HOA Cases

In McDaniel, the prosecution attempted to use the defendant’s mother’s statement to show an adoptive admission by the defendant because the defendant did not text his mother back to deny her indirect accusation that he had committed several local robberies. The Court of Appeal rejected that theory. As the Court of Appeal explained, given the nature of text messaging, the fact that the defendant did not text his mother back was not sufficient to show he had adopted his mother’s statement:

Text messaging is different from in person and phone conversations in that text exchanges are not always instantaneous and do not necessarily occur in “real time.” Rather, text messages may not be read immediately upon receipt and the recipient may not timely respond to a text message for any number of reasons, such as distraction, interruption, or the press of business. Furthermore, people exchanging text messages can typically switch, relatively quickly and seamlessly, to other forms of communication, such as a phone call, social-media messaging, or an in-person discussion, depending on the circumstances. In short, in light of the distinctive nature of text messaging, the receipt of a text message does not automatically signify prompt knowledge of its contents by the recipient, and furthermore, the lack of a text response by the recipient does not preclude the possibility that the recipient responded by other means, such as a phone call. source

Several California laws dictate how electronic communications can be authenticated.

- Below are the evidence code numbers and examples of when they may apply:Means of Authenticating and Proving Writings

- Evidence Code § 1401.

(a) Authentication of a writing is required before it may be received in evidence.

(b) Authentication of a writing is required before secondary evidence of its content may be received in evidence.There are several ways to authenticate and prove a writing under Evidence Code sections 1410-1421.

ARTICLE 2. Means of Authenticating and Proving Writings [1410 – 1421]

- Evidence Code § 1410 – the evidence code does not limit the means by which communication may be authenticated.

content may be received in evidence.

1410.Nothing in this article shall be construed to limit the means by which a writing may be authenticated or proved.Testimony of a Witness with Personal Knowledge: Section 1410 allows for authentication of a writing through the testimony of a witness who has personal knowledge of the writing’s origin or content. For example, in a forgery case, a defense attorney might call a handwriting expert to testify that the signature on a contested document doesn’t match the defendant’s genuine signature, thereby undermining the authenticity of the document.Comparison with a Genuine Exemplar: Section 1411 states that if the authenticity of a questioned document is in dispute, a comparison with a known, genuine exemplar can be used to establish its authenticity. For instance, in a case involving check fraud, the defense can present a check signed by the defendant and compare the signatures to prove the questioned document’s authenticity.Expert Opinion: In cases where the authenticity of a writing is complex and may require specialized knowledge, section 1412 allows for expert testimony. For example, in a grand theft case involving digital evidence, a forensic expert might be called upon to authenticate emails, texts, or other electronically stored data. - 1410.5.

- (a) For purposes of this chapter, a writing shall include any graffiti consisting of written words, insignia, symbols, or any other markings which convey a particular meaning.

- (b) Any writing described in subdivision (a), or any photograph thereof, may be admitted into evidence in an action for vandalism, for the purpose of proving that the writing was made by the defendant.

- (c) The admissibility of any fact offered to prove that the writing was made by the defendant shall, upon motion of the defendant, be ruled upon outside the presence of the jury, and is subject to the requirements of Sections 1416, 1417, and 1418.

- 1411. Except as provided by statute, the testimony of a subscribing witness is not required to authenticate a writing.

- 1412. If the testimony of a subscribing witness is required by statute to authenticate a writing and the subscribing witness denies or does not recollect the execution of the writing, the writing may be authenticated by other evidence.

- 1413. A writing may be authenticated by anyone who saw the writing made or executed, including a subscribing witness.

Evidence Code § 1413 – a witness saw the person send the message and attests to witnessing this actionDistinctive Characteristics: Section 1413 provides that when a writing has distinctive characteristics, these can be used for authentication. For example, in a cybercrime case, the unique digital signature of a hacker’s code might be used to authenticate the writing, connecting it to the defendant. - Cal. Evid. Code § 1414

Section 1414 – Admissions of authenticity- The party against whom it is offered has at any time admitted its authenticity; or

- The writing has been acted upon as authentic by the party against whom it is offered.

Evid. Code § 1414 Enacted by Stats. 1965, Ch. 299.

Public Records and Reports: Public records and reports made by a public officer in accordance with legal requirements are considered self-authenticating pursuant to section 1414. For example, in an embezzlement case where a defendant’s prior convictions for identity theft are relevant, the defense attorney can introduce certified court records to prove the authenticity of these documents.

Ancient Documents: Section 1415 states that documents over 30 years old are deemed authentic as long as they are in a condition that creates no suspicion of alteration. In a 35 year old homicide trial, the prosecution may introduce the defendant’s old diary entry confessing to the murder to prove the authenticity of certain events.

Documents Executed Under Seal: Documents with an official seal are self-authenticating and do not require further authentication under section 1416.

Certified Copies: Section 1417 states that in criminal cases that involve documents such as arrest records, certified copies from the custodian of records can be introduced as evidence, provided they are properly certified.

Documents in the Regular Course of Business: Section 1418 states that business records made in the regular course of business are considered authentic. For example, in a real estate fraud case, an attorney can introduce financial records from a company’s accounting department to prove the authenticity of financial transactions.

- 1415. A writing may be authenticated by evidence of the genuineness of the handwriting of the maker.

- 1416. A witness who is not otherwise qualified to testify as an expert may state his opinion whether a writing is in the handwriting of a supposed writer if the court finds that he has personal knowledge of the handwriting of the supposed writer. Such personal knowlegde may be acquired from:

- (a) Having seen the supposed writer write;

- (b) Having seen a writing purporting to be in the handwriting of the supposed writer and upon which the supposed writer has acted or been charged;

- (c) Having received letters in the due course of mail purporting to be from the supposed writer in response to letters duly addressed and mailed by him to the supposed writer; or

- (d) Any other means of obtaining personal knowledge of the handwriting of the supposed writer.

- 1417.The genuineness of handwriting, or the lack thereof, may be proved by a comparison made by the trier of fact with handwriting(a) which the court finds was admitted or treated as genuine by the party against whom the evidence is offered or (b) otherwise proved to be genuine to the satisfaction of the court.

- 1418.The genuineness of writing, or the lack thereof, may be proved by a comparison made by an expert witness with writing (a) which the court finds was admitted or treated as genuine by the party against whom the evidence is offered or (b) otherwise proved to be genuine to the satisfaction of the court.

- 1419.Where a writing whose genuineness is sought to be proved is more than 30 years old, the comparison under Section 1417 or 1418 may be made with writing purporting to be genuine, and generally respected and acted upon as such, by persons having an interest in knowing whether it is genuine.

- Evidence Code § 1420 – the context of the message shows the message was a reply from the person in questionCollateral Documents: Sometimes, a document is not directly at issue but is related to the case. In these instances, section 1420 states that the collateral document can be introduced to help prove the authenticity of the primary document. For example, a defense attorney may use a surveillance video from a nearby store to corroborate the authenticity of a defendant’s alibi in a robbery case.

1420A writing may be authenticated by evidence that the writing was received in response to a communication sent to the person who is claimed by the proponent of the evidence to be the author of the writing. - Evidence Code § 1421 – in the message itself, the person says something that only they would knowPhone Records: In cases involving cell phone records, Section 1421 allows attorneys to use records provided by phone service providers to authenticate call logs and text messages. This may be crucial in cases related to cybercrimes or communication between individuals involved in criminal activities. A writing may be authenticated by evidence that the writing refers to or states matters that are unlikely to be known to anyone other than the person who is claimed by the proponent of the evidence to be the author of the writing.1421.A writing may be authenticated by evidence that the writing refers to or states matters that are unlikely to be known to anyone other than the person who is claimed by the proponent of the evidence to be the author of the writing. source source source

Proof of declarant’s perception by his statement presents similar considerations when declarant is identified. People v. Poland, 22 Ill.2d 175, 174 N.E.2d 804 (1961). However, when declarant is an unidentified bystander, the cases indicate hesitancy in upholding the statement alone as sufficient, Garrett v. Howden, 73 N.M. 307, 387 P.2d 874 (1963); Beck v. Dye, 200 Wash. 1, 92 P.2d 1113 (1939), a result which would under appropriate circumstances be consistent with the rule.

Texts / Emails AS EVIDENCE:

ELECTRONICALLY STORED INFORMATION IN COURT

Text / Email Specific

ARE TEXT MESSAGES ADMISSIBLE IN COURT? AFTER AN ACCIDENT THE OTHER DRIVER ADMITTED SHE WASN’T PAYING ATTENTION. IN A TEXT LATER THE DRIVER SAID SHE WAS SORRY, THAT SHE’D BEEN ON THE CELL PHONE, AND OFFERED TO PAY OUTSIDE OF INSURANCE. NOW THAT HER INSURANCE COMPANY IS INVOLVED SHE DENIES EVERYTHING. IS THE TEXT ADMISSIBLE IN COURT?

If you watch those TV court shows you may have seen them admit texts without a thought. Remember they have to get everything in between the commercials.

In an actual court of law electronically stored information, or “ESI”, faces several tests under the rules of evidence.

ESI includes texts, emails, chat room conversations, websites and other digital postings. In court, admitting ESI requires passing these steps:

- Is the electronic evidence relevant?

- Can it pass the test of authenticity?

- Is it hearsay?

- Is the version of ESI offered the best evidence?

- Is any probative value of the ESI outweighed by unfair prejudice?

The text must pass each step. Failing any one means it’s excluded. Proving relevance poses a relatively simple challenge. But meeting the authenticity requirement raises larger questions.

Establishing the identity of the sender of a text is critical to satisfying the authentication requirement for admissibility. Showing the text came from a person’s cell phone isn’t enough. Cell phones are not always used only by the owner.

Courts generally require additional evidence confirming the texter’s identity. Circumstantial evidence corroborating the sender’s identity might include the context or content of the messages themselves.

HEARSAY RULE AND ELECTRONICALLY STORED INFORMATION

Text messages and other ESI are hearsay by nature. The hearsay rule blocks admission of out of court statements offered to prove the truth of the matter at issue. But court rules, which vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, are full of exceptions and definitions of “non hearsay”.

Here, the text by the other driver that she wasn’t paying attention at the time of the car accident should qualify as an admission, a prior statement by the witness or a statement by a party opponent.

TEXTS AND ‘BEST EVIDENCE’ RULE

Two more layers remain in the evidentiary hurdle. ESI presents its own challenges in passing the ‘best evidence rule’ or the ‘original writing rule’. Essentially the rules require introduction of an original, a duplicate original or secondary evidence proving the version offered to the court is reliable.

The final test requires that the probative value of the evidence not be outweighed by considerations including unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues or needless presentation of cumulative evidence.

ESI AND TEXTS AS EVIDENCE: WHY SO HARD?

Sometimes the challenge isn’t as overwhelming as it seems. In a federal case in which I was involved the court addressed all five steps of the process in ten minutes and admitted a series of texts. But a federal magistrate in Maryland wrote a 101 page decision thoroughly detailing the above process, rejecting some emails.

These are the evidence issues confronting texts and any electronically stored information. But, people who fail to object to evidence waive their right to object later, including upon appeal. Evidence of all kinds sometimes sneaks in despite the rules. So, go through the analysis long before running up the courthouse steps. source

Introducing Digital Evidence in California State Courts

- Victim testified he knew the number from which text was sent because Defendant told him the number. The contents of the texts referred to victim as a snitch. The defendant called the victim during the course of the text message conversation. [(Butler v. State, 459 S.W. 3d 595 (Crim. Ct App. Tx. April 22, 2015].)

- Testimony of records custodian from telecommunications company, explaining how company kept records of actual content of text messages, the date and time text messages were sent or received, and the phone number of the individuals who sent or received the messages, provided proper foundation for, and sufficiently authenticated, text messages admitted into evidence in trial on armed robbery charges. (Fed.Rules Evid.Rule 901(a), U.S. v. Carr (11th Cir. 2015) 607 Fed.Appx. 869.)

- Ten of 12 text messages sent to victim’s boyfriend from victim’s cellular telephone following sexual assault were not properly authenticated to extent that State’s evidence did not demonstrate that defendant was author of text messages. (Rodriguez v. State (2012) 128 Nev. Adv. Op. 14, [273 P.3d 845].)

- Murder victim’s cell phone recovered from scene of crime. Forensic tools used on phone recovered texts back and forth between victim and defendant. (People v. Lehmann (Cal. Ct. App., Sept. 17, 2014, No. G047629) 2014 WL 4634272 [Unpublished].)

- Defendant laid an inadequate foundation of authenticity to admit, in prosecution for assault with a deadly weapon, hard copy of e‑mail messages (Instant Messages) between one of his friends and the victim’s companion, as there was no direct proof connecting victim’s companion to the screen name on the e‑mail messages. (People v. Von Gunten (2002 Cal.App.3d Dist.) 2002 WL 501612. [Unpublished].) G. Authenticating Metadata: Another way in which electronic evidence may be authenticated is by examining the metadata for the evidence. Metadata, “commonly described as ‘data about data,’ is defined as ‘information describing the history, tracking, or management of an electronic document.’

Metadata is ‘information about a particular data set which describes how, when and by whom it was collected, created, accessed, or modified and how it is formatted (including data demographics such as size, location, storage requirements and media information).’ Some examples of metadata for electronic documents include: a file’s name, a file’s location (e.g., directory structure or pathname), file format or file type, file size, file dates (e.g., creation date, date of last data modification, date of last data access, and date of last metadata modification), and file permissions (e.g., who can read the data, who can write to it, who can run it).

Some metadata, such as file dates and sizes, can easily be seen by users; other metadata can be hidden or embedded and unavailable to computer users who are not technically adept.” Because metadata shows the date, time and identity of the creator of an electronic record, as well as all changes made to it, metadata is a distinctive characteristic of all electronic evidence that can be used to authenticate it under Federal Rule 901(b)(4). Although specific source code markers that constitute metadata can provide a useful method of authenticating electronically stored evidence, this method is not foolproof because, “[a]n unauthorized person may be able to obtain access to an unattended computer.

Moreover, a document or database located on a networked-computer system can be viewed by persons on the network who may modify it. In addition, many network computer systems usually provide authorization for selected network administrators to override an individual password identification number to gain access when necessary.

Metadata markers can reflect that a document was modified when in fact it simply was saved to a different location. Despite its lack of conclusiveness, however, metadata certainly is a 7 | Introducing Digital Evidence in California State Courts useful tool for authenticating electronic records by use of distinctive characteristics.”

(Lorraine v. Markel American Ins. Co. (D. Md. 2007) 241 F.R.D. 534, 547–48 [citations omitted].) F. Challenges to Authenticity Challenges to the authenticity of computer records often take on one of three forms. First, parties may challenge the authenticity of both computer-generated and computer-stored records by questioning whether the records were altered, manipulated, or damaged after they were created. Second, parties may question the authenticity of computer-generated records by challenging the reliability of the computer program that generated the records. California state courts have refused to require, as a prerequisite to admission of computer records, testimony on the “acceptability, accuracy, maintenance, and reliability of … computer hardware and software.”

(People v. Lugashi (1988) 205 Cal.App.3d 632, 642.) As Lugashi explains, although mistakes can occur, “ ‘such matters may be developed on cross-examination and should not affect the admissibility of the [record] itself.’ (People v. Martinez (2000) 22 Cal.4th 106, 132.) Third, parties may challenge the authenticity of computer-stored records by questioning the identity of their author. For further information, please consult “Defeating Spurious Objections to Electronic Evidence,” by Frank Dudley Berry, Jr., or Chapter 5 – Evidence of the United States Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section Criminal Division, Searching and Seizing Computers and Obtaining Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations (2009) (accessed Aug. 18, 2016). III. Hearsay Rule The first question to ask is whether or not the information within the document is hearsay. If it is hearsay, then you need an applicable exception, such as business and government records or statement by party opponent. Examples of things that are not hearsay include; 1) operative facts and 2) data that is generated by a mechanized process and not a human declarant and, 3) A statement being used to show its falsity not its truth. source

Why Would Someone Need to Authenticate Text Messages for Court?

In the contemporary age of technology, digital evidence is becoming increasingly important in court. Here is how to authenticate text messages for court in California.

Text messages are unfortunately a form of digital media that can easily be photoshopped and manipulated. This puts the evidence at risk of interference or invalidity. Additionally, text messages fall under the jurisdiction of California Evidence Code Section 250, which prevents any evidence from being used without first being authenticated.

Related: Can Text Messages Be Used in California Divorce Court?

How to Introduce Digital Evidence in California State Courts

Smartphones allow endless mobile communication that can be crucial evidence for a court case. In order to present documents and electronic evidence in a California state court, the accumulation of evidence must follow the California Electronic Communication Privacy Act (CPOA). The California Electronic Communication Privacy Act protects the privacy of individuals and their electronic devices, and it requires law enforcement to receive a warrant before they can access any electronic information.

To be in compliance with the CPOA, digital evidence must prove to be necessary for furthering the case. Additionally, in order to be sustainable in court, digital evidence must meet the following four components:

- It must be relevant.

- It must be authenticated.

- Its contents must not be inadmissible hearsay (able to be disproven as fake).

- It must withstand a “best evidence” objection.

Proposed digital evidence must meet the standards of both the CPOA and the four aforementioned components. The only exceptions to the protection of privacy that the CPOA ensures are if the individual gives consent or if the exception qualifies as an emergency situation. In order to meet the requirements of an emergency circumstance, the government entity must “in good faith, believe that an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to any person requires access to the electronic device information” (CPOA).

Additionally, if the evidence contains metadata, the proponents must address the metadata separately. Metadata is data about the date, for example, a time stamp on a screenshot in a text message. The proponents would need to consider the time and prepare an additional foundation for it.

The Four Components of Evidence Required Getting Authentication of Text Messages

Relevance is determined by the evidence’s ability to prove or disprove any disputed fact, including credibility. In order for digital evidence to qualify as relevant, the defendant must usually be tied to the evidence being presented. Specifically, the proponent must be able to make a connection between the defendant and either the phone number that sent or received the text.

Authentication of evidence requires the proponent to introduce sufficient evidence to hold that the writing is what they are claiming it is. To authenticate a text message it must hold that “by evidence the writing refers to or states matters that are unlikely to be known to anyone other than the person who is claimed by the prominent of the evidence to be the author of the writing.” California Evidence Code Section 1421.

There are no published California cases that distinctly lay out the requirements for authenticating a text message, but unpublished California opinions are consistent with the rules set for authenticating emails and chats. This includes a combination of both direct and circumstantial evidence. Here are some examples of unpublished opinions from California:

- The murder victim’s cell phone was recovered from the scene of the crime. The forensic tools used on the phone recovered the texts back and forth between victim and defendant. (People v. Lehmann (Cal. Ct. App., Sept. 17, 2014, No. G047629) 2014 WL 4634272 [Unpublished].)

- 10 of 12 text messages sent to the victim’s boyfriend from the victim’s cellular telephone following sexual assault were not properly authenticated to extent that the State’s evidence did not demonstrate that the defendant was the author of the messages. (Rodriguez v. State (2012) 128 Nev. Adv. Op. 14, [273 P.3d 845].) source