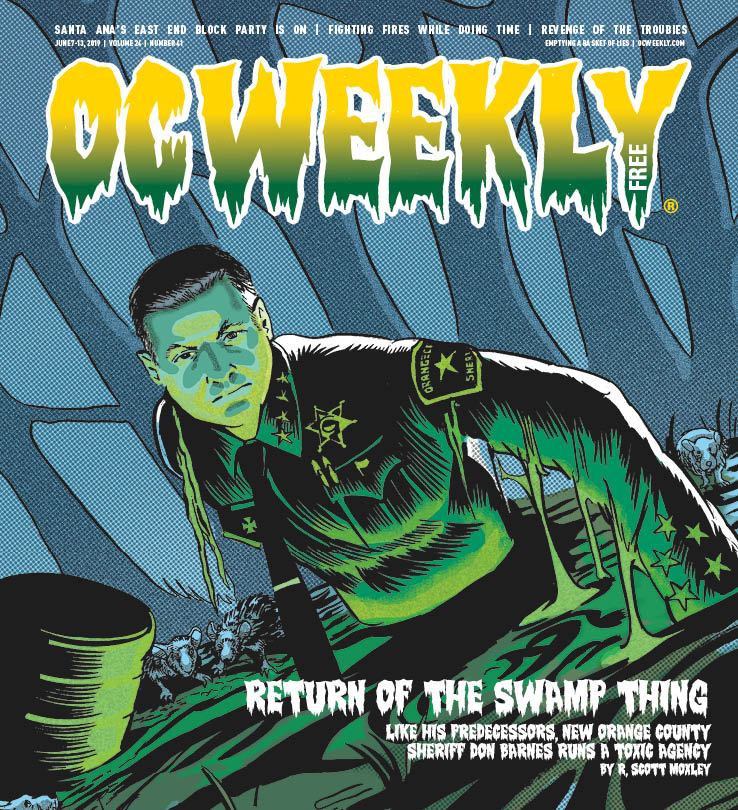

New Orange County Sheriff Don Barnes Runs a Toxic Agency

CHAPTER ONE

For bored cops seeking action, there’s probably no easier place to score than the Southern California motels where petty drug dealers rendezvous with users. At 12:45 p.m. on Feb. 15, 2016, that sweet spot for Deputy Nicholas Petropulos of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department (OCSD) was the parking lot at the Extended Stay of America in Yorba Linda near the 91 freeway. Though a fellow officer assigned to investigate events of that afternoon would later falsify an official record to help justify Petropulos’ deadly presence, the deputy had received no call for help.

First as a cop in Brea, and then, beginning in 2012, with the OCSD, Petropulos knew that Extended Stay, located a few miles from the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, was his proverbial shooting-fish-in-a-barrel site. During his career, he’d conducted approximately 100 investigations there, usually involving minor transactions and yielding an average of 20 arrests per year.

On that February afternoon, Petropulos returned to his favorite hunting ground and, sure enough, observed what he considered highly suspicious activity: Two people talking to each other in the parking lot. Brandon Lee Witt was sitting in the driver’s seat of a gold, four-door Toyota Avalon, while Manuel Drought stood nearby. Neither man screamed, ran or brandished a weapon. But Petropulos’ suspicion intensified when the men made what he considered another eyebrow-raising move: They dared to look at him as he slowly drove his patrol vehicle by while staring at them.

In the end, that reasoning wasn’t necessary to explore what horrific crimes could be under way, as Petropulos had found his legal hook for escalation. Witt’s car didn’t show a front license plate, a California Vehicle Code infraction. The deputy drove out of view, stopped and waited. When nothing more happened, he returned to the scene. “I decided to investigate,” he eventually explained under oath.

After parking the OCSD cruiser at an angle that allowed his patrol video-recording system (PVS) to catch the upcoming encounter’s audio, but thwarted it from capturing meaningful video, Petropulos approached Witt, who’d remained in his car. The deputy asked, “What’s going on, man?”

Witt replied, “I’m in the middle of moving.”

“Do you have anything in the car illegal?”

“No.”

“Anything I need to worry about?”

“Not at all.”

“Is this your car?”

“Yeah. . . . Did I do anything wrong?”

“You had no front plate on the car when I looked at it earlier.”

“It’s right here.”

Having been previously victimized by a person impersonating an officer, Witt was frightened to obey commands to exit the car. He asked the deputy, “Can I verify your identity?” And, “Can I at least call your sergeant?”

Petropulos wasn’t happy with the questions. “You’re lucky I haven’t ripped you right out.”

Voicing concern that Witt might be using his right hand to reach for a weapon, the deputy began grabbing him.

“Hey, there’s no need to touch me like that,” Witt said.

“Dude, I swear to God,” Petropulos replied.

“Look, stop,” Witt said. “Why are you assaulting me?”

Claiming he wasn’t getting full compliance with his commands, the deputy launched a series of lethal threats, saying, “I’m going to shoot you!”

Witt pleaded, “No.”

“I’m going to fucking shoot you,” said Petropulos, who would unholster his department-issued Glock handgun.

“I’m scared,” said Witt. “I’m scared.”

The banter continued with Witt alarmed by the deputy’s aggression and the deputy frustrated that his suspect allegedly wouldn’t keep his right hand in plain sight.

“You’re going to get shot, motherfucker!” Petropulos declared.

“No, please don’t!” Witt cried. “Please!”

Neither the deputy nor Brian Callagy, a fellow cop who arrived as backup, saw the suspect holding a knife or a gun or even the appearance of a weapon anywhere inside the car. If anyone should have been in fear for his life, it was the 39-year-old Witt, who’d consumed methamphetamines that day. Unarmed and surrounded by two deputies, he posed no immediate threat.

Petropulos said, “Fuck it,” placed the Glock at point-blank range on Witt’s left shoulder and fired.

There was a moan, and then nothing. According to an autopsy, the 40 mm bullet ripped through the victim’s arm, chest, ribs, heart, diaphragm and liver. Witt’s right foot had hit the gas in reaction, causing the Toyota to race over a curb and crash into a concrete drainage ditch. Though still-spinning tires produced smoke, there was no movement inside the vehicle. Bleeding profusely and unconscious, a dying Witt was left unattended for a period of time because, the deputy claims, he still believed Witt might reach for a gun.

In the aftermath, Petropulos—who makes more than $255,000 annually in public funds—told a tale at odds with the audio recording and probability. According to the deputy, a seated and miraculously strong Witt used his left hand to “pull parts of my shoulder and upper body through the window of the vehicle” while his right hand extended in the opposite direction searching for that nonexistent gun.

Petropulos hoped that people would believe Witt tried to drive away with him hanging halfway out the Toyota’s window. He also declared himself the victim of a felony assault by an “aggressive” suspect. He noted he’d suffered a light bruise and scratch on his right arm. It was enough to make him “fear for my life,” the deputy said.

Employment of that well-worn catchphrase, whether genuine or not, often acts as a legal prophylactic for police seeking immunity from courthouse accountability, but additional chapters in the Witt saga were yet to be written.

CHAPTER TWO

Chicago police were on the lookout in October 2014 for an auto burglary suspect when they spotted 17-year-old Laquan McDonald acting bizarrely on the street while holding a 3-inch knife.

McDonald, who was high on PCP, disobeyed commands to drop the knife. But nine of the 10 cops on the scene saw no reason to gun him down.

Officer Jason Van Dyke, however, wasn’t in any mood for de-escalation. He waited all of six seconds after exiting his patrol vehicle to shoot McDonald in the back, driving him to the pavement. With the suspect still down, the cop emptied the rest of his magazine, firing 15 more bullets from his 9 mm semi-automatic handgun. An autopsy determined McDonald had been shot in his chest, neck, head, both arms, right leg and back.

The follow-up investigation by the Chicago Police Department ruled the homicide “justified” after rewriting history. The department accepted Van Dyke’s story that McDonald had pointed the knife blade and “lunged” at him. That tale bolstered the cop’s report that he’d been scared and feared for his life.

Months later, police weren’t able to keep wraps on all the videos of the shooting, footage that contradicted Van Dyke’s version of events. The knife in McDonald’s hand had been folded when found at the scene, and he’d never lunged. There was also evidence that cops destroyed valuable dash-cam videos and “intentionally damaged” audio recordings of the killing.

Disgusted by the incident, community groups hosted numerous emotional street protests. The City Council gave McDonald’s family a $5 million settlement and hoped there would be no further embarrassing revelations of police corruption tied to the case that a civil trial might uncover. Van Dyke’s prosecutor told a jury that none of the shots was necessary. The panel convicted Van Dyke for murder and 16 counts of battery for each fired bullet. During a January sentencing hearing, he received a prison punishment of six years and nine months.

But there’s a fascinating twist: Not everybody agreed on who’d been victimized. Embedded among cop ranks were people in denial. A cop-union official told a reporter the jury was “duped” and had “stabbed” police “in the back.” Another said, “The Chicago Police Department is standing with an officer we think acted as an officer.”

It’s not just in Chicago where police routinely protect their own scoundrels with lies, doctored evidence and media campaigns.

CHAPTER THREE

“Each deputy must be entrusted with well-reasoned discretion in determining the appropriate use of force in each incident,” OCSD policy states. “The use of force to accomplish unlawful objectives is prohibited. The Department will not tolerate excessive and/or punitive force.”

Those statements are noble theories—not reality. Excessive force is often celebrated in the department run by Sheriff Donald Barnes. Beating someone unconscious or taking a life can be a precursor to career advancement and bigger salaries.

Deputy Michael Devitt bolstered his résumé about 30 minutes before sunrise on Aug. 19, 2018, when he approached a passed-out man who was slumped over in the driver’s seat of a black Jeep. Mohamed Sayem had been out drinking the night before and decided to sleep off his insobriety in the parking lot of a pool hall and bar. Devitt’s verbal efforts didn’t wake Sayem, so the deputy opened the car door, removed the key from the ignition and began shaking the suspect, who was clearly inebriated. Asked for identification, a mumbling Sayem handed the officer his Bic lighter.

To be fair, there’s no doubt Devitt and his colleague on the scene, Eric Ota, had a duty to investigate the situation. But after telling Sayem to stay in the Jeep, Devitt began grabbing the suspect, who recoiled and said there was no reason for the aggression. “Don’t touch me like that,” Sayem said.

The deputy then yanked the wobbly suspect out of the vehicle, punched him in the stomach and violently slammed his fist into the man’s face six times. The third blow knocked Sayem unconscious. Ota then helped Devitt throw Sayem face-down to the pavement before handcuffing the man. Sayem regained consciousness and asked if they were going to shoot him.

“[I’d] like to,” said Ota.

Four minutes later, with the sun on the verge of rising, OCSD Sergeant Christopher Hibbs arrived and Devitt explained events. He said he’d grabbed an uncooperative Sayem and yanked him out of the Jeep “to control him.” He’d “punched him probably four times on the right side of his face” because Sayem was “basically standing over me now, and he is way taller than I am,” according to an audio recording.

He added that the suspect tried to “bear hug” him, though dash-cam video shows Sayem’s right hand clutching the steering wheel until he was punched unconscious.

Two other deputies arrived, Blake Blaney and Brant Lewis, and all five officers huddled around the hood of Devitt’s patrol vehicle. The topic of their conversation? Recent beatings of suspects. At one point, Blaney said, “That was a good fight!”

Lewis boasted, “I got in another good one last week.”

Moments later, the deputies realized that Hibbs’ body mic was still on. Lewis walked over to his superior officer and turned it off; the chatting resumed.

For a deputy trying to talk his way out of an excessive-force case, Hibbs was the ideal boss. In September 2007, near the Anaheim-Stanton border, he’d grown angry with Ignacio Lares, a suspect who refused to give his real name. Though Lares was handcuffed and secured in the back of a patrol car without leg room, Hibbs twice fired his Taser weapon. To justify his violence, he claimed he’d felt physically threatened and in danger. But prosecutors believed it was a classic case of excessive force and charged him after securing damning testimony from five other officers—Trent Hoffman, Robert Long, Bryan Thomas, Rob Gunzel and James Wicks—who’d witnessed the tasing. OCSD management, including then-Sheriff Sandra Hutchens, and the deputies’ union protested the Hibbs case as unfair.

At the Fullerton trial, which I covered, each of the law-enforcement witnesses diverted from their grand-jury testimony by claiming severe memory loss. Dozens and dozens of times, they testified, “I don’t recall” or, “I don’t remember.” An elderly, male-dominated jury then voted 11 to 1 for acquittal. In fact, three of the jurors told me afterward that Hibbs should have shot Lares. Disgusted prosecutors said they’d witnessed the police “code of silence” in action.

A bit more than a decade later, Hibbs heard Devitt’s first oral explanation for the attack on Sayem. In a newer version written when all the deputies had huddled at the scene and had turned off their mics, he embellished the danger he faced with acts that are not recorded on dash-cam video. Now, Sayem supposedly grabbed his utility vest and refused to let go, the implication being that the suspect was trying to grab a weapon. “I believed Sayem was going to continue to try to physically assault me,” he wrote to justify the beating.

Memory loss had aided Hibbs in his own excessive-force case. With Devitt’s altered tale on his desk, perhaps he thought he’d extend the same courtesy he’d received. He ignored the discrepancies and signed the official report as legitimate.

CHAPTER FOUR

It’s standard practice for deputies to conduct surveillance on a property long before a planned raid. But that’s not what happened at 6:30 on an April 2003 morning in North Orange County. About a dozen gun-pointing OCSD gang and narcotics deputies broke down the front door of Roberto “Pino” Peralez’s tiny 88-year-old home. If they’d followed procedure, they would have known the 69-year-old heroin addict had already left to comply with a court-ordered daily dose of methadone at a Stanton community clinic.

Pissed that he’d missed his target, Deputy Joe Balicki raced to the clinic in an unmarked vehicle and found Peralez driving his decades-old burgundy GMC Safari van toward him. The addict was on his way home, unaware of the raid.

But drug use had taken its toll. Peralez was a fragile figure at 5-foot-7 with bad eyes and bad hearing, according to his daughter.

Balicki jumped in front of the slow-moving, dilapidated van and pointed a 9 mm Sig Sauer handgun at Peralez. Seconds later, three bullets pierced the windshield and destroyed the unarmed man’s heart. He died instantly.

An exhilarated (some thought cocky) Balicki told fellow officers that he’d felt his life had been in danger. He then drove to a nearby McDonald’s for breakfast and to wait for the OCSD public-relations unit to spin its magic. It worked, at least in the Los Angeles Times, which published the headline “Driver, 69, Shot Dead as He Tries to Ram Deputies.”

This killer was never held accountable in either criminal or civil court. In fact, Balicki took delight in ending Peralez’s life. To celebrate his feat, the sniper-trained deputy placed a trophy of sorts on his OCSD desk: an enlarged photograph of the three tight bullet holes in the victim’s windshield.

CHAPTER FIVE

The unexpected, unnecessary death of Witt, a Garden Grove native, left his relatives in shock. The 6-foot-1, 165-pound Witt—who’d struggled with drug addiction, according to his Vietnamese American ex-girlfriend—loved to travel with friends and family. At a church memorial service, his relatively short life was celebrated.

Gary Witt and Kathy Craig, Witt’s separated parents, hired Scott D. Hughes of Newport Beach and Dale K. Galipo of Woodland Hills to represent them in a federal wrongful-death lawsuit against OCSD and Petropulos. Hughes and Galipo reported that deputies had punched and kicked Witt’s face and head after pulling his dying body from the crashed Toyota.

“Witt never attempted to punch, kick or verbally threaten anyone,” the attorneys told U.S. District Court Judge Cormac J. Carney in their March 2017 complaint. “He was unarmed and posed no imminent threat of death or serious physical injury to either Petropulos or any other person [throughout the incident]. . . . There was no objectively reasonable justification for [the deputy] to resort to the tactics that he did.”

Lawyers privately retained at taxpayer expense by the County of Orange on behalf of the defendants spent months trying to kill the lawsuit before it could reach a jury. They claimed the parents didn’t technically qualify for the right to sue. They sought immunity from accountability for Petropulos because he is a cop. They argued it had been a righteous killing, and therefore, a jury had no facts to consider opposite of their stance. They battled against the plaintiffs’ right to call a police expert who would testify the deputy’s conduct had been unprofessional. They even demanded that a future jury never learn that Witt had been unarmed.

When Carney rejected their points as meritless, the county’s Board of Supervisors appealed to the U.S. District Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. But they lost there, too. In May, a jury determined that Petropulos used excessive force, violated Witt’s constitutional rights and acted with “malice” in the killing. They awarded the parents $3.4 million.

CHAPTER SIX

When it comes to the daily protection of deputies caught in ethical messes, the job falls to Orange County’s County Counsel (OCCC). For example, in OCSD’s notorious jailhouse-informant scandal, the OCCC helped deputies disobey judicially demanded records that assisted in illustrating how they ran unconstitutional scams, hid or destroyed embarrassing evidence, and repeatedly committed perjury. At the height of the scandal in mid-2017, Catherine Irons, a then-retired lieutenant, testified that OCCC and OCSD secretly agreed to withhold key informant records.

In the Sayem case, the OCCC assigned Kayla Watson the task of shielding Devitt, Ota and Hibbs from accountability. Watson told Judge Kevin Haskins and Sayem defense attorney, Assistant Public Defender Scott Sanders, a lie at a pretrial hearing in December; she claimed that Hibbs had written only one report on the case and that the defense had already received it.

After an in-camera session between only Haskins, Watson and OCSD sergeant Anthony Patella, the judge emerged and announced he saw nothing the defense was entitled to receive. A surprised Sanders asked if he’d seen any use-of-force documents. Haskins said the sheriff’s department had surrendered no such evidence.

About a week later, Watson reappeared in court. She conceded Hibbs had written a six-page use-of-force report and that she had known of its existence, but that the sheriff’s department didn’t want it released, even though the defense was entitled to see it. Sanders saw multiple reasons why the document had been hidden; it shows that Hibbs omitted Devitt’s first unhelpful explanation for the beating, and it also documented he’d obtained and reviewed Ota’s dash cam to reach his conclusions.

But that’s a huge problem for Watson and OCSD. They had failed to surrender Ota’s dash-cam video. When confronted by Sanders, Watson said there is no Ota footage. Haskins then forced Hibbs to sign a declaration backing up that assertion. The sergeant claimed he’d erroneously written he’d watched the video when he hadn’t because it doesn’t exist.

The Ota audio from the dash cam is, as department officials surely know, crucial. It would cover an 11-minute gap at the scene when Devitt revised his story while surrounded by the other four deputies. “Hibbs helped Devitt to conceal the truth about his assault on [Sayem],” said Sanders, who plans to press for more honest disclosures at a hearing this month. “The charge of felony resisting an officer against my client should have been dismissed long ago.”

CHAPTER SEVEN

The brutal September 2015 restaurant/bar murder of college student Shayan Mazroei by Craig Tanber shocked Laguna Niguel, where homicides are rare. The killing also set off a series of scandals. Did Tanber, once a member of the white-supremacist, criminal street gang Public Enemy Number One Death Squad (PEN1), commit a hate crime, as the victim’s family believes? Causing public protests, prosecutors declined to pursue that angle, but they found themselves in a nightmare as they watched OCSD deputies botch another simple case with stunning unprofessionalism.

When asked how he’d helped capture Tanber at a Garden Grove motel after days on the run, deputy Victor Valdez oddly invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination during a grand jury hearing. Valdez had given $300 during the manhunt to his confidential informant, Adriean Vasquez, the mother of Tanber’s son, and asked her to lure the wanted man to her motel room for an ambush. Vasquez is the daughter of Gina Peterson, who has ties to The Real Housewives of Orange County and once dated Dennis Rodman, the unofficial U.S. ambassador to North Korea and a legendary basketball player.

Under oath, Valdez refused to say whether he’d conducted an illegal operation against Tanber on the grounds that his answer might incriminate him. Deputy Public Defender Alisha Montoro, who represents the accused killer, believes the evidence shows Valdez had a—politely put—romantic history with Vasquez and ordered her to buy heroin and inject a massive dose into Tanber’s arm as a way to subdue him in her motel room that was surrounded by surveillance conducted by OCSD’s North Gang Enforcement Team (NGET), a cowboy crew that enjoyed calling itself the “Jumpout Boys.” (These boys liked to chat amongst themselves about blowjobs, pornography, fornication and partying with female informants while on duty, according to court records.) Once officers had the handcuffed fugitive in their patrol vehicle, they launched an unconstitutional recorded interrogation despite him being exceptionally high.

That pretrial murder case is still playing out inside Orange County’s Central Courtroom, but prosecutorial inspections into the conduct of Valdez, who’d erased his phone upon learning he was under investigation, and his partner, Phil Avalos, uncovered not only their cozy, personal relationships with Vasquez, who said OCSD gave her heroin as a snitch reward in addition to cash for squealing on her narcotics-trafficking pals, but also other highly suspicious activities.

This week, Montoro tried to ask Valdez, who is currently assigned to patrol Mission Viejo, questions about his conduct in Tanber, but he again invoked his Fifth Amendment privilege. She then turned to Avalos, who’d become Vasquez’s “handler” after Valdez left the unit that focuses on Stanton area gangs such as Crow Village. Avalos conceded on the witness stand that he’d sent Vasquez—a heroin addict who called him “hon” and supplied him with breast pics—advance notice that undercover agents were snooping around her motel, looking to make drug arrests. He had to admit that fact because Montoro found proof in text messages. Avalos, who wears the best poker face I’ve ever seen, insisted he had been “joking.”

But this 17-year deputy and onetime high-school resources cop, falsified official crime reports on at least four occasions. In each case, he claimed he’d placed confiscated weapons, drug paraphernalia, methamphetamine or cocaine into the department’s evidence locker when he hadn’t. There’s no dispute. Asked by Montoro if he falsified reports, Avalos answered, “Correct.”

“I did not know I lost it until it was brought to my attention,” he testified. “It is by accident [I’d failed to book that evidence].”

Pressed by Montoro, the deputy admitted it is “possible” he placed the missing evidence with the wrong defendants, but he wouldn’t know how to discover who he might have smeared.

During an June 5 hearing, Vasquez testified that deputy Valdez demanded she give him photographs of her vagina and that once, with Avalos standing watch outside the patrol vehicle, he angrily told her he wanted to “face fuck her.”

CHAPTER EIGHT

After the OCSD deputies’ chicanery or uses of force when facing imaginary threats, they suffered the following fates: Petropulos won “deputy of the year” honors; Barnes awarded Devitt a coveted assignment craved by his 2,000 sworn colleagues and, in recent weeks, promoted report-falsifier Avalos to sergeant; Hibbs also landed a pay raise and sergeant’s job; Valdez kept his job and Balicki rose high through the ranks. He now works as a commander on Barnes’ executive staff, the one lamely asserting that anyone who questions the department’s lack of ethics is “anti-law enforcement.”

CNN-featured investigative reporter R. Scott Moxley has won Journalist of the Year honors at the Los Angeles Press Club; been named Distinguished Journalist of the Year by the LA Society of Professional Journalists; obtained one of the last exclusive prison interviews with Charles Manson disciple Susan Atkins; won inclusion in Jeffrey Toobin’s The Best American Crime Reporting for his coverage of a white supremacist’s senseless murder of a beloved Vietnamese refugee; launched multi-year probes that resulted in the FBI arrests and convictions of the top three ranking members of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department; and gained praise from New York Times Magazine writers for his “herculean job” exposing entrenched Southern California law enforcement corruption.

cited from https://www.ocweekly.com/don-barnes-orange-county-sheriff/