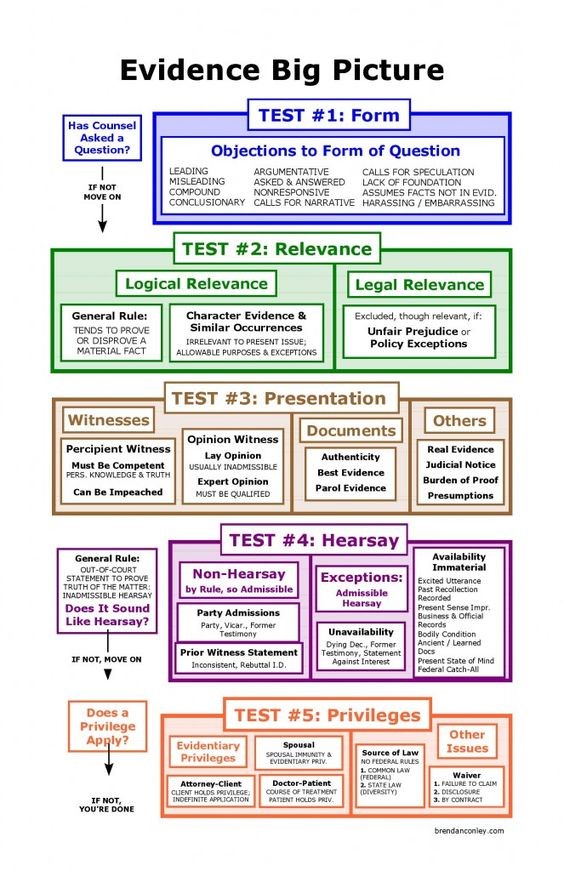

Major Exceptions To The Hearsay Rule

REVIEW OF THE CALIFORNIA HEARSAY RULE – EVIDENCE CODE 1200

California’s “hearsay rule,” defined under Evidence Code 1200, is a law that states that third-party hearsay cannot be used as evidence in a trial. This rule is based on the principle that hearsay is often unreliable and cannot be cross-examined.

In other words, EC 1200 is the statute that makes hearsay generally inadmissible in any court proceedings. The description of hearsay is straightforward. It’s a statement made by someone other than the testifying witness that is offered to prove the truth.

The legal definition of the hearsay rule under Evidence Code 1200 says: “(a) “Hearsay evidence” is evidence of a statement that was made other than by a witness while testifying at the hearing and that is offered to prove the truth of the matter stated…except as provided by law, hearsay evidence is inadmissible.”

The primary reason for this rule of evidence in California criminal cases is that hearsay statements are not reliable enough to be accepted as valid evidence. Further, they are not made under oath and can’t be subjected to cross-examination in court.

A traditional hearsay example includes a scenario where a witness testifies that a friend told them the defendant confessed to committing the crime. Still, the friend who allegedly told them does not provide testimony.

While the hearsay rule is intended to protect the defendant and ensure fairness, it is more than a little confusing because there are so many exceptions that it can be challenging to determine what is and is not “acceptable” hearsay. Our Los Angeles criminal defense attorneys will explore this rule in more detail below to clear up some of that confusion.

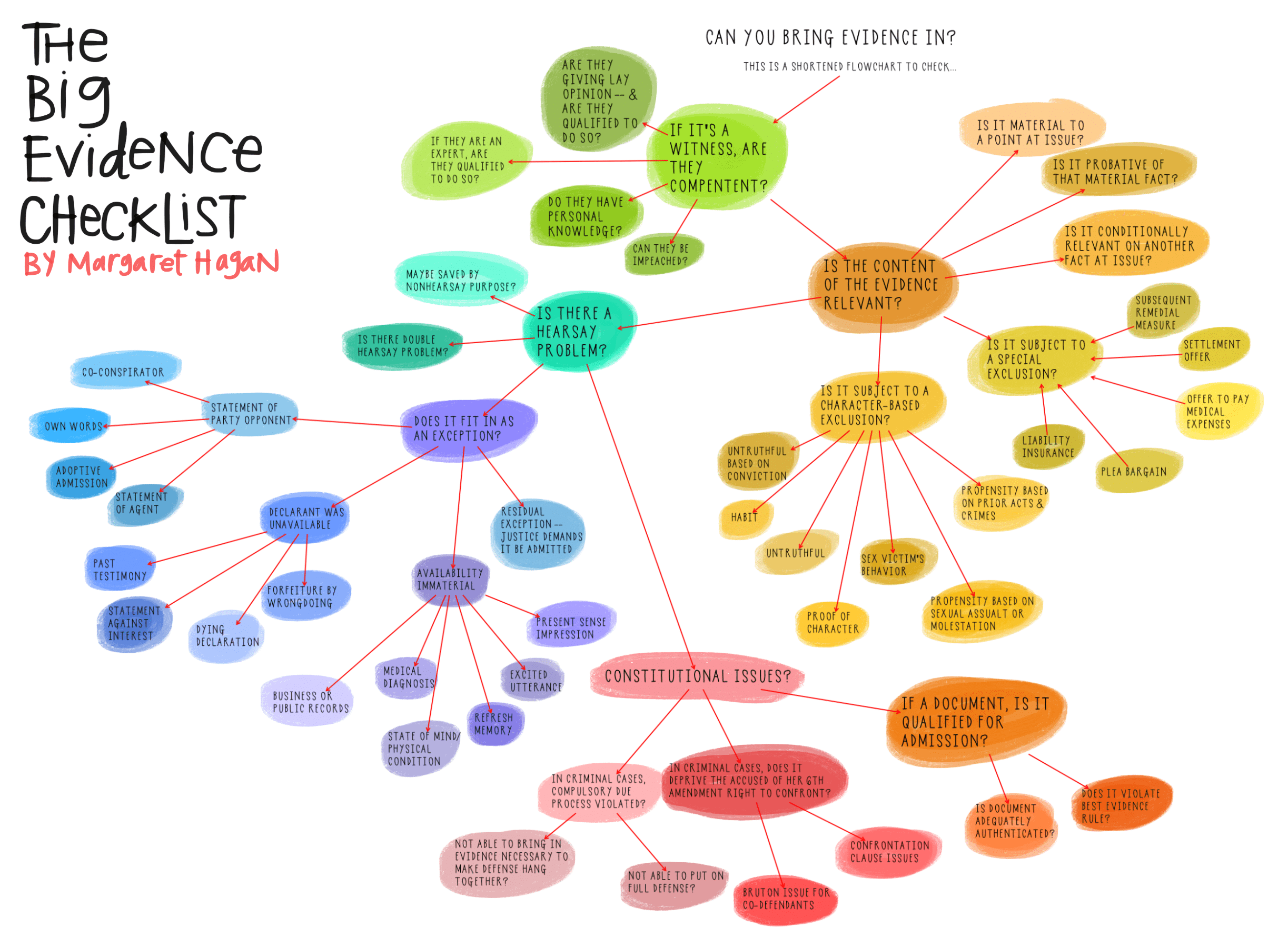

WHAT IS HEARSAY?

Evidence Code 1200 defines hearsay evidence as evidence of a statement made other than by a witness while testifying at the hearing and that is offered to prove the truth of the matter stated.

To put it simply, hearsay occurs when a witness shares something someone else said out of court. It becomes “hearsay evidence” when the attorney attempts to use that out-of-court statement to confirm a fact they’re trying to establish.

A “statement” could mean a verbal statement, a written statement, or nonverbal conduct such as hand gestures, head shaking, or shoulder shrugging. This rule applies to criminal and civil trials and hearings held as part of the pretrial process and sentencing hearings.

WHY DOES THE HEARSAY RULE EXIST?

There are two main reasons why the hearsay rule exists. In general, they are not usually considered admissible evidence in court as they are deemed unreliable:

- Third-hand statements are frequently unreliable. Like in the game “telephone,” the more often a word is repeated between people, the more it can deviate from what was first said. Hearsay is unreliable because human memory is often unreliable;

- Hearsay can’t be cross-examined. One of the rights guaranteed in the Sixth Amendment is that defendants have the right to cross-examine those who testify against them. Hearsay is a statement made out of court by someone not on the stand, so the statement can’t be verified by cross-examination.

Suppose the prosecution offers a statement that is not made by a witness at a trial and claims their statement is true. In that case, the defense doesn’t have the opportunity to cross-examine that witness to prove their statement is not valid. Next, let’s examine the Evidence Code 1200 hearsay rule exceptions below.

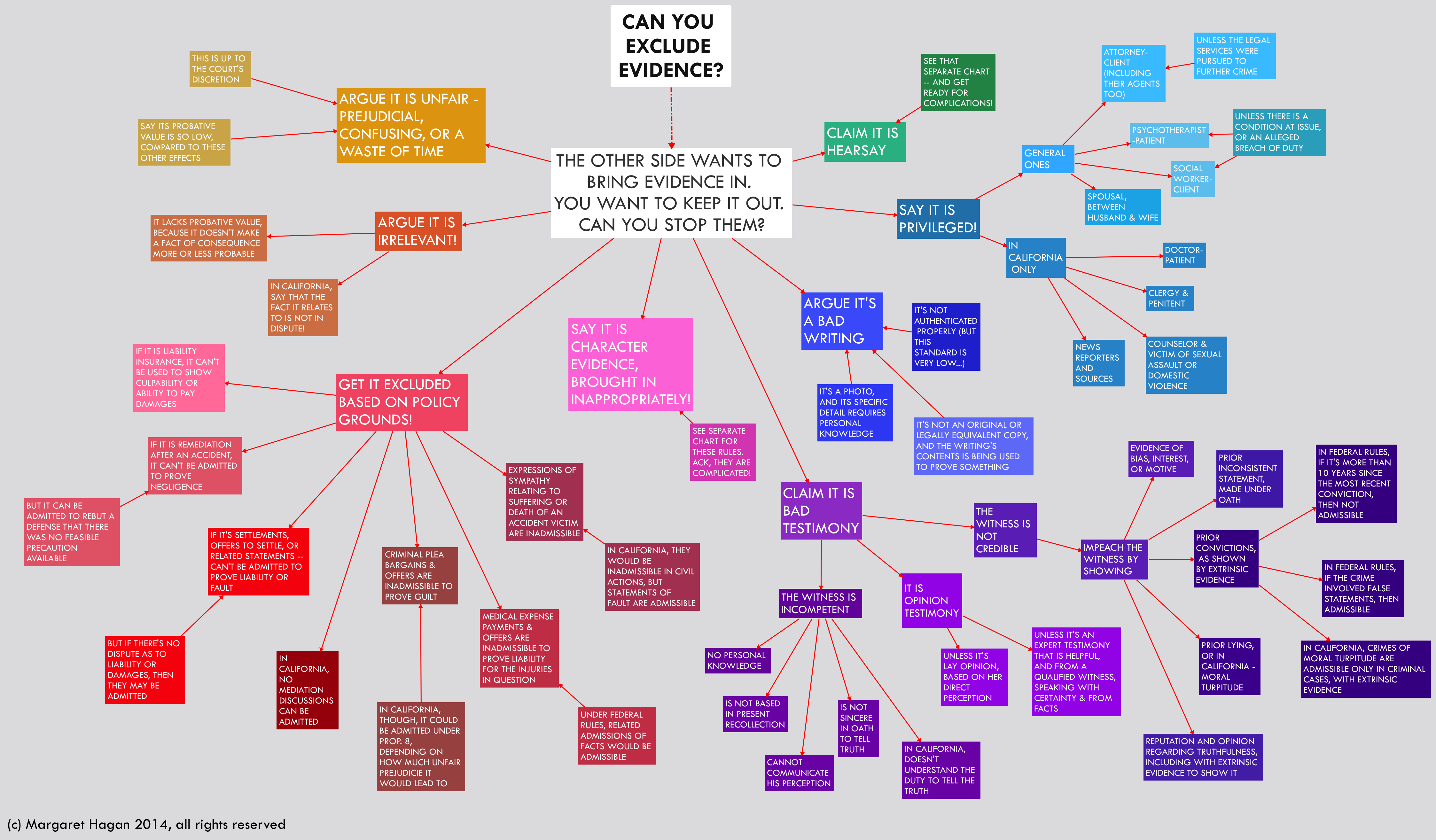

WHAT ARE THE HEARSAY EXCEPTIONS?

Even though hearsay generally can’t be used as evidence against a defendant, California law has established more than a dozen exceptions to the rule—instances in which hearsay is considered admissible without being unfair to the defendant. Some of the most notable exceptions include the following but are not limited to.

Hearsay admissions made by defendant against themselves – Evidence Code 1220

If a witness relates a self-incriminating statement allegedly made by the defendant out of court (e.g., admitting to the crime), that statement can be used against the defendant even though it’s technically hearsay.

Statements made against one’s interest – Evidence Code 1230

If the witness relates hearsay that damages their interests (e.g., implicates them in a crime), it’s more reliable because no reasonable person would inflict self-damage unless the statement were true. This is known as “declarations against interest,” which are out-of-court statements contrary to the speaker’s best interest that no rational person would make unless true.

Prior inconsistent statements – Evidence Code EC 1235

Hearsay may be admissible when used to show inconsistency in a witness’ statements on the stand, e.g., a witness relates something said by another witness that doesn’t jibe with what the first witness said in court. This is considered reliable because it impeaches, or discredits, the witness’ testimony.

Further, under Evidence Code 1236 EC, if a prior inconsistent statement of a witness is presented at trial as noted above, or the other side suggested their testimony is fabricated or biased, then the witness’s side could give their prior out-of-court statements that are consistent with their testimony to show it’s reliable.

Deathbed/dying declarations – Evidence Code 1242

A dying declaration is a statement made by someone on their deathbed about how they were injured or what happened to them. These are allowed as evidence because it’s not likely that someone would lie about information relevant to their death when they believe it is imminent.

Spontaneous statements – Evidence Code 1240

A spontaneous statement is one by a speaker spontaneously as an event is happening—a statement that is not the result of questioning by law enforcement or another party. These statements are admissible as hearsay because the speaker does not tailor their story to fit a pre-determined narrative.

Previously recorded recollections or identification – Evidence Code 1237

If a witness’s memory of an event was previously captured in a written or recorded format (e.g., via notes, video, audio recordings), that may be used as hearsay evidence if the witness’s memory of the event is fuzzy and the witness testifies that the recollection is accurate. This exception applies to both identification of the defendant in a lineup and statements made by witnesses about relevant events.

Business records – Evidence Code 1271

Records kept in the ordinary course of business are considered reliable evidence and thus may be used as hearsay in court. This exception includes everything from ledgers to financial statements to email correspondence.

Certain written records are admissible evidence if they were made in the regular course of a business and made near the time of the act. Further, a qualified witness will have to testify how it was prepared to show its reliability.

Statements made by child abuse and elder abuse victims.

Victims of child abuse or child sex crimes under the age of 12 do not have to testify in court; neither do elder abuse victims (elder dependents over age 65). In such cases, video or recorded statements made by these victims are admissible in court.

Out-of-court statements in cases involving serious sex crimes against children, like Penal Code 261 PC rape and Penal Code 288 PC lewd acts with a minor, are admissible if they are made by a child under 12 and made in a written report by police or an employee in the welfare department.

Unavailable witnesses for serious felonies only – Evidence Code 1350

In serious felony cases, prior statements made by a witness who was killed or kidnapped to prevent them from testifying may be admitted as hearsay evidence.

This exception to the rule applies in a California criminal trial when the defendant is charged with a serious felony crime. There is clear and convincing evidence that the person making the hearsay statement has been made unavailable by the defendant, either through homicide or kidnapping, along with other requirements.

Other exceptions to the hearsay rule include former testimony under Evidence Code 1291, physical injury statements, and Penal Code 368 elder abuse statements under Evidence Code 1380. source

Hearsay Evidence

Created by FindLaw’s team of legal writers and editors | Last updated February 12, 2019

The rule against hearsay is deceptively simple, but it is full of exceptions. At its core, the rule against using hearsay evidence is to prevent out-of-court, second hand statements from being used as evidence at trial given their potential unreliability.

Hearsay Defined

Hearsay is defined as an out-of-court statement, made in court, to prove the truth of the matter asserted. These out-of-court statements do not have to be spoken words, but they can also constitute documents or even body language. The rule against hearsay was designed to prevent gossip from being offered to convict someone.

Exceptions to the Rule Against Hearsay Evidence

Hearsay evidence is not admissible in court unless a statue or rule provides otherwise. Therefore, even if a statement is really hearsay, it may still be admissible if an exception applies. The Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) contains nearly thirty of these exceptions to providing hearsay evidence.

Generally, state law follows the rules of evidence as provided in the Federal Rules of Evidence, but not in all cases. The states can and do vary as to the exceptions that they recognize.

Most Common Hearsay Exceptions

There are twenty-three exceptions in the federal rules that allow for out-of-court statements to be admitted as evidence even if the person made them is available to appear in court. However, only a handful of these are regularly used. The three most popularly used exceptions are:

- Present Sense Impression. A hearsay statement may be allowed if it describes or explains an event or condition and was made during the event or immediately after it.

- Excited Utterance. Closely related to the present sense impression is the hearsay exception for an excited utterance. The requirements for this exception to apply is that there must have been a startling event and the declarant made the statement while under the excitement or stress of the event.

- Then-Existing Mental, Emotional, or Physical Condition. A statement that is not offered for the truth of the statement, but rather to show the state of mind, emotion or physical condition can be an exception to the rule against hearsay evidence. For instance, testimony that there was a heated argument can be offered to show anger and not for what was said.

Other Exceptions to Rule Against Hearsay Evidence

In addition to the three most common exceptions for hearsay, there are several other statements that generally will be accepted as admissible evidence. These fall into three categories:

- Medical: Statements that are made to a medical provider for the purpose of diagnosis or treatment.

- Reputation: Statements about the reputation of the person, their family, or land boundaries.

- Documents: These documents typically include business records and government records, but can include learned treatises, family records, and church records.

Hearsay Exceptions if the Declarant is Unavailable to Testify in Court

There are exceptions to the rule against the admissibility of hearsay evidence that apply only when the declarant is unavailable. A declarant is considered unavailable in situations such as when:

- The court recognizes that by law the declarant is not required to testify;

- The declarant refuses to testify;

- The declarant does not remember;

- The declarant is either dead or has a physical or mental illness the prevents testimony; or

- The declarant is absent from the trial and has not been located.

If the declarant is deemed to be unavailable, then the following type of evidence can be ruled admissible in court. This includes:

- Former testimony;

- Statements made under belief of imminent death;

- Statements against a person’s own interest; and

- Statements of personal or family history.

Catchall Exception to the Rule against Hearsay

Finally, the last exception is the so-called “catchall” rule. It provides that evidence of a hearsay statement not included in one of the other exceptions may nevertheless be admitted if it meets these following conditions:

- It has sound guarantees of trustworthiness

- It is offered to help prove a material fact

- It is more probative than other equivalent and reasonably obtainable evidence

- Its admission would forward the cause of justice

- The other parties have been notified that it will be offered into evidence

Defenses Against Hearsay Evidence

If the court admits hearsay evidence under one the exceptions, then the credibility of the person offering the statement may be attacked. This attack must be supported by admissible evidence, but can be prior inconsistent statement, bias, or some other evidence that would show that the declarant has a reason to lie or not to remember accurately. source

A. Identifying Hearsay Testimony or Documents

Hearsay is an out-of-court statement offered to prove the truth of the matter

stated. Cal. Evid. Code § 1200(a); Fed. R, Evid. (“FRE”) 801(c).

The hearsay rule excludes out-of-court statements submitted for their truth, except

as provided by law —such as when it falls within an established exception. Cal, Evid.

Code § 1220, et seq.; FRE 801(c), 803, 804 and 807.

The rationale for excluding out-of-court statements attempted to be used in court

for their truth is the lack of tnistworthiness and reliability of such evidence.

Statements made out of court were not subject to cross examination at the time

they were made and, as such, may be unreliable as substantive proof. Moreover, cross

examination at trial is not necessarily a substitute for this problem of lack of cross

examination at the time the statement was made. Buchanan v. Nye (1954) 128

Cal.App.2d 582, 585; FRE SO1(d)(i) (Adv. Comm. Notes).

This remains true even if the out-of-court statement was made under oath, such as

in a prior deposition, sworn declaration, report, or even at a prior trial or hearing.

Out-of-court statements used to prove the truth of the matter stated are admissible,

however, if they fall within one of the recognized exceptions to the rule. These

exceptions carry the necessary indicia of reliability and trustworthiness from the

circumstances under which they are made.

Moreover, what may, at first blush, appear to be hearsay, may in fact be non

hearsay.

Conduct may or may not be hearsay depending on the circumstances. Non-verbal

conduct that is intended to be a substitute for words is hearsay if offered in Court to prove the truth of what was intended to be a communication. FRE SO 1(a) and. (e); Cal. Evid. Code § 225

Where the out-of-court statement is offered for some purpose other than for its

tnith, it is not hearsay. Cal. Evid. Code § 1200(a); FRE 801(c). The hearsay rule is not

implicated where the issue is whether something happened, or something was said, or

done. In these situations, the statements or events or dates are operative facts and hence.non-hearsay. See, e.g., FRE 801(c).

Likewise, out-of-court statements used for impeachment purposes are not hearsay.

The out-of-court statements are not being used for their truth, but rather to attack the

witness’ credibility. See, e.g., FRE 613.

An out-of-court statement by a party opponent may be used for its truth and for

impeachment purposes.

Examples of statements that may be deemed non-hearsay include: alleging false

representations, statements related to real property transactions, contract formation,

defamation, discriminatory practices, authorization, knowledge of events, to establish

residency, identity, and the like.

B. Objecting to an Opponent’s Use of Hearsay

- Evaluate for what purpose ostensible hearsay evidence will be used. (Is it hearsay?)

- If it is, is there a recognized exception or statute that permits its use?

- Motions in limine.

- Authentication and foundation.

- Preliminary determinations by court. Cal. Evid. Code §§ 402, et seq.

- Hearsay proponent bears the burden of proving non-hearsay, hearsay but

with an exception, non-availability of witness, and so forth.

C. Demonstrating How Evidence Falls Under Hearsay Exception

The “classic” hearsay exceptions are:

- Admissions. Cal. Evid. Code §§ 1220-1227, FRE 801{d){2)(A}-{E).

- Declarations against interest. Cal. Evict. Code § 1230; FRE 804(b)(3).

- Prior statements or testimony. Cal. Evict. Code §§ 1235-1238, 1291-1293;

FRE $04(b)(1); cf. FRE 801(d)(1)(A). - Present-sense impressions/excited utterances. Cal. Evict. Code §§ 1240,

1241; FRE 803(1). - Dying declarations. Cal. Evict. Code § 1242; FRE 804(b)(2).

- Judgments, orders, etc. are hearsay, but may be used for non-hearsay

purposes, and judicial notice of their existence may be taken for purposes

of proving a prior adjudication took place for yes judicata/collateral

estoppel purposes. - State of mindlbody. Cal. Evict. Code §§ 1250, 1251; FRE 803(5).

- Business records. Cal. Evict. Code §§ 1270, 1271, 1272; FRE 803(6) and (7).

- Public or official records. Cal. Evict. Code §§ 1280-1284; cf. §§ 1270

1272; FRE 803(8). - Federal hearsay “catch-all” exception. FRE 807 (A proposed amendment

is to take effect December 1, 2019.)

D. Handling Double Hearsay

Each level of hearsay must be analyzed independently, and each level must fall

within one of the established exceptions or qualify as non hearsay. Cal. Evict. Code §

1201; FRE 805.

E. Avoiding Hearsay Objections

Think carefully about the purpose of the evidence you are seeking to admit. Is it

even necessary? Is it cumulative?

Does the use of the evidence Have more than one purpose -one. which is not

hearsay?

Have you established relevance and laid the proper foundation?

Have you considered California Evidence Code § 352

Section 352. 352. The court in its discretion may exclude evidence if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the probability that its admission will (a) necessitate undue consumption of time or (b) create substantial danger of undue prejudice, of confusing the issues, or of misleading the jury.

Have you considered California Evidence Code § FRE 403?

Rule 403. Excluding Relevant Evidence for Prejudice, Confusion, Waste of Time, or Other Reasons

The court may exclude relevant evidence if its probative value is substantially outweighed by a danger of one or more of the following: unfair prejudice, confusing the issues, misleading the jury, undue delay, wasting time, or needlessly presenting cumulative evidence.

Notes

(Pub. L. 93–595, §1, Jan. 2, 1975, 88 Stat. 1932; Apr. 26, 2011, eff. Dec. 1, 2011.)

Notes of Advisory Committee on Proposed Rules

The case law recognizes that certain circumstances call for the exclusion of evidence which is of unquestioned relevance. These circumstances entail risks which range all the way from inducing decision on a purely emotional basis, at one extreme, to nothing more harmful than merely wasting time, at the other extreme. Situations in this area call for balancing the probative value of and need for the evidence against the harm likely to result from its admission. Slough, Relevancy Unraveled, 5 Kan. L. Rev. 1, 12–15 (1956); Trautman, Logical or Legal Relevancy—A Conflict in Theory, 5 Van. L. Rev. 385, 392 (1952); McCormick §152, pp. 319–321. The rules which follow in this Article are concrete applications evolved for particular situations. However, they reflect the policies underlying the present rule, which is designed as a guide for the handling of situations for which no specific rules have been formulated.

Exclusion for risk of unfair prejudice, confusion of issues, misleading the jury, or waste of time, all find ample support in the authorities. “Unfair prejudice” within its context means an undue tendency to suggest decision on an improper basis, commonly, though not necessarily, an emotional one.

The rule does not enumerate surprise as a ground for exclusion, in this respect following Wigmore’s view of the common law. 6 Wigmore §1849. Cf. McCormick §152, p. 320, n. 29, listing unfair surprise as a ground for exclusion but stating that it is usually “coupled with the danger of prejudice and confusion of issues.” While Uniform Rule 45 incorporates surprise as a ground and is followed in Kansas Code of Civil Procedure §60–445, surprise is not included in California Evidence Code §352 or New Jersey Rule 4, though both the latter otherwise substantially embody Uniform Rule 45. While it can scarcely be doubted that claims of unfair surprise may still be justified despite procedural requirements of notice and instrumentalities of discovery, the granting of a continuance is a more appropriate remedy than exclusion of the evidence. Tentative Recommendation and a Study Relating to the Uniform Rules of Evidence (Art. VI. Extrinsic Policies Affecting Admissibility), Cal. Law Revision Comm’n, Rep., Rec. & Studies, 612 (1964). Moreover, the impact of a rule excluding evidence on the ground of surprise would be difficult to estimate.

In reaching a decision whether to exclude on grounds of unfair prejudice, consideration should be given to the probable effectiveness or lack of effectiveness of a limiting instruction. See Rule 106 [now 105] and Advisory Committee’s Note thereunder. The availability of other means of proof may also be an appropriate factor.

California Hearsay Objections – Hearsay Admission Exceptions

Admissions – Evidence of a statement is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule when offered against the declarant in an action to which he is a party in either his individual or representative capacity, regardless of whether the statement was made in his individual or representative capacity. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1220]

Adoptive Admissions – Evidence of a statement offered against a party is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the statement is one of which the party, with knowledge of the content thereof, has by words or other conduct manifested his adoption or his belief in its truth.[Cal. Evid. Code § 1221]

Authorized Admissions – Evidence of a statement offered against a party is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if: (a) The statement was made by a person authorized by the party to make a statement or statements for him concerning the subject matter of the statement; and (b) The evidence is offered either after admission of evidence sufficient to sustain a finding of such authority or, in the court’s discretion as to the order of proof, subject to the admission of such evidence. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1222]

Co-Conspirators’ Admissions – Evidence of a statement offered against a party is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if:

- (a) The statement was made by the declarant while participating in a conspiracy to commit a crime or civil wrong and in furtherance of the objective of that conspiracy;

- (b) The statement was made prior to or during the time that the party was participating in that conspiracy;

- and (c) The evidence is offered either after admission of evidence sufficient to sustain a finding of the facts specified in subdivisions (a) and (b) or, in the court’s discretion as to the order of proof, subject to the admission of such evidence. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1223]

Declarant’s Liability – When the liability obligation, or duty of a party to a civil action is based in whole or in part upon the liability, obligation, or duty of the declarant, or when the claim or right asserted by a party to a civil action is barred or diminished by a breach of duty by the declarant, evidence of a statement made by the declarant is as admissible against the party as it would be if offered against the declarant in an action involving that liability, obligation, duty, or breach of duty. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1224]

Statement of Right or Title – When a right, title, or interest in any property or claim asserted by a party to a civil action requires a determination that a right, title, or interest exists or existed in the declarant, evidence of a statement made by the declarant during the time the party now claims the declarant was the holder of the right, title, or interest is as admissible against the party as it would be if offered against the declarant in an action involving that right, title, or interest. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1225]

Minor’s Injuries – Evidence of a statement by a minor child is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if offered against the plaintiff in an action brought under Section 376 of the Code of Civil Procedure for injury to such minor child. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1226]

Wrongful Death – Evidence of a statement by the deceased is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if offered against the plaintiff in an action for wrongful death brought under Section 377 of the Code of Civil Procedure. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1227]

Declarations Against Interest – Evidence of a statement by a declarant having sufficient knowledge of the subject is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the declarant is unavailable as a witness and the statement, when made, was so far contrary to the declarant’s pecuniary or proprietary interest, or so far subjected him to the risk of civil or criminal liability, or so far tended to render invalid a claim by him against another, or created such a risk of making him an object of hatred, ridicule, or social disgrace in the community, that a reasonable man in his position would not have made the statement unless he believed it to be true. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1230]

Prior Inconsistent Statement – Evidence of a statement made by a witness is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the statement is inconsistent with his testimony at the hearing and is offered in compliance with Section 770. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1235]

Prior Consistent Statement – Evidence of a statement previously made by a witness is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the statement is consistent with his testimony at the hearing and is offered in compliance with Section 791. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1236]

Past Recollection Recorded [Cal. Evid. Code § 1237]

- (a) Evidence of a statement previously made by a witness is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the statement would have been admissible if made by him while testifying, the statement concerns a matter as to which the witness has insufficient present recollection to enable him to testify fully and accurately, and the statement is contained in a writing which:

- (1) Was made at a time when the fact recorded in the writing actually occurred or was fresh in the witness’ memory;

- (2) Was made

- (i) by the witness himself or under his direction or

- (ii) by some other person for the purpose of recording the witness’ statement at the time it was made;

- (3) Is offered after the witness testifies that the statement he made was a true statement of such fact; and

- (4) Is offered after the writing is authenticated as an accurate record of the statement.

- (b) The writing may be read into evidence, but the writing itself may not be received in evidence unless offered by an adverse party.

Prior Identification – Evidence of a statement previously made by a witness is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the statement would have been admissible if made by him while testifying and: (a) The statement is an identification of a party or another as a person who participated in a crime or other occurrence; (b) The statement was made at a time when the crime or other occurrence was fresh in the witness’ memory; and (c) The evidence of the statement is offered after the witness testifies that he made the identification and that it was a true reflection of his opinion at that time. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1238]

Spontaneous Statement – Evidence of a statement is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the statement: (a) Purports to narrate, describe, or explain an act, condition, or event perceived by the declarant; and (b) Was made spontaneously while the declarant was under the stress of excitement caused by such perception. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1240]

Contemporaneous Statement – Evidence of a statement is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the statement: (a) Is offered to explain, qualify, or make understandable conduct of the declarant; and (b) Was made while the declarant was engaged in such conduct. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1241]

Dying Declaration – Evidence of a statement made by a dying person respecting the cause and circumstances of his death is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the statement was made upon his personal knowledge and under a sense of immediately impending death. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1242]

State of Mind [Cal. Evid. Code § 1250]

- (a) Subject to Section 1252, evidence of a statement of the declarant’s then existing state of mind, emotion, or physical sensation (including a statement of intent, plan, motive, design, mental feeling, pain, or bodily health) is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule when:

- (1) The evidence is offered to prove the declarant’s state of mind, emotion, or physical sensation at that time or at any other time when it is itself an issue in the action; or

- (2) The evidence is offered to prove or explain acts or conduct of the declarant.

- (b) This section does not make admissible evidence of a statement of memory or belief to prove the fact remembered or believed.

Statement of Declarant’s Previously Existing Mental/Physical State – Subject to Section 1252, evidence of a statement of the declarant’s state of mind, emotion, or physical sensation (including a statement of intent, plan, motive, design, mental feeling, pain, or bodily health) at a time prior to the statement is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if: (a) The declarant is unavailable as a witness; and (b) The evidence is offered to prove such prior state of mind, emotion, or physical sensation when it is itself an issue in the action and the evidence is not offered to prove any fact other than such state of mind, emotion, or physical sensation.[Cal. Evid. Code § 1251]

Testamentary Statements [Cal. Evid. Code § 1260]

Business Records – Evidence of a writing made as a record of an act, condition, or event is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule when offered to prove the act, condition, or event if:

- (a) The writing was made in the regular course of a business;

- (b) The writing was made at or near the time of the act, condition, or event;

- (c) The custodian or other qualified witness testifies to its identity and the mode of its preparation; and

- (d) The sources of information and method and time of preparation were such as to indicate its trustworthiness. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1271]

Absence of Business Records – Evidence of the absence from the records of a business of a record of an asserted act, condition, or event is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule when offered to prove the nonoccurrence of the act or event, or the nonexistence of the condition, if:

- (a) It was the regular course of that business to make records of all such acts, conditions, or events at or near the time of the act, condition, or event and to preserve them; and

- (b) The sources of information and method and time of preparation of the records of that business were such that the absence of a record of an act, condition, or event is a trustworthy indication that the act or event did not occur or the condition did not exist. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1272]

Official Records – Evidence of a writing made as a record of an act, condition, or event is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule when offered in any civil or criminal proceeding to prove the act, condition, or event if all of the following applies: (a) The writing was made by and within the scope of duty of a public employee. (b) The writing was made at or near the time of the act, condition, or event. (c) The sources of information and method and time of preparation were such as to indicate its trustworthiness. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1280]

Absence of Official Records – Evidence of a writing made by the public employee who is the official custodian of the records in a public office, reciting diligent search and failure to find a record, is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule when offered to prove the absence of a record in that office [Cal. Evid. Code § 1284]

Vital Statistics – Evidence of a writing made as a record of a birth, fetal death, death, or marriage is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the maker was required by law to file the writing in a designated public office and the writing was made and filed as required by law. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1281]

California Vital Statistics [Cal. Health and Safety Code § 10577]

Federal Records [Cal. Evid. Code § 1282, 1283]

A written finding of presumed death made by an employee of the United States authorized to make such finding pursuant to the Federal Missing Persons Act (56 Stats. 143, 1092, and P.L. 408, Ch. 371, 2d Sess. 78th Cong.; 50 U.S.C. App. 1001–1016), as enacted or as heretofore or hereafter amended, shall be received in any court, office, or other place in this state as evidence of the death of the person therein found to be dead and of the date, circumstances, and place of his disappearance. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1282]

An official written report or record that a person is missing, missing in action, interned in a foreign country, captured by a hostile force, beleaguered by a hostile force, beseiged by a hostile force, or detained in a foreign country against his will, or is dead or is alive, made by an employee of the United States authorized by any law of the United States to make such report or record shall be received in any court, office, or other place in this state as evidence that such person is missing, missing in action, interned in a foreign country, captured by a hostile force, beleaguered by a hostile force, besieged by a hostile force, or detained in a foreign country against his will, or is dead or is alive. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1283]

Former Testimony [Cal. Evid. Code §§ 1290, 1291, 1292]

As used in this article, “former testimony” means testimony given under oath in: (a) Another action or in a former hearing or trial of the same action; (b) A proceeding to determine a controversy conducted by or under the supervision of an agency that has the power to determine such a controversy and is an agency of the United States or a public entity in the United States; (c) A deposition taken in compliance with law in another action; or (d) An arbitration proceeding if the evidence of such former testimony is a verbatim transcript thereof. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1290]

- (a) Evidence of former testimony is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the declarant is unavailable as a witness and:

- (1) The former testimony is offered against a person who offered it in evidence in his own behalf on the former occasion or against the successor in interest of such person; or

- (2) The party against whom the former testimony is offered was a party to the action or proceeding in which the testimony was given and had the right and opportunity to cross-examine the declarant with an interest and motive similar to that which he has at the hearing.

- (b) The admissibility of former testimony under this section is subject to the same limitations and objections as though the declarant were testifying at the hearing, except that former testimony offered under this section is not subject to:

- (1) Objections to the form of the question which were not made at the time the former testimony was given.

- (2) Objections based on competency or privilege which did not exist at the time the former testimony was given. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1291]

- (a) Evidence of former testimony is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if:

- (1) The declarant is unavailable as a witness;

- (2) The former testimony is offered in a civil action; and

- (3) The issue is such that the party to the action or proceeding in which the former testimony was given had the right and opportunity to cross-examine the declarant with an interest and motive similar to that which the party against whom the testimony is offered has at the hearing.

- (b) The admissibility of former testimony under this section is subject to the same limitations and objections as though the declarant were testifying at the hearing, except that former testimony offered under this section is not subject to objections based on competency or privilege which did not exist at the time the former testimony was given. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1292]

Judgments [Cal. Evid. Code § 1300, 1302]

Ancient Writings [Cal. Evid. Code § 1331]

Commercial and Scientific Publications [Cal. Evid. Code § 1340]

General Interest [Cal. Evid. Code § 1341]

Corroborative Evidence [PG&E v. G.W. Thompson Drayage & Rigging Co. (1968) 69 Cal.2d 33; Rodgers v. Kemper Constr. Co. (1975) 50 Cal.App.3d 608]

Family History Statement [Cal. Evid. Code § 1310]

Family History Record [Cal. Evid. Code §§ 1312, 1315, 1316]

Family History Reputation [Cal. Evid. Code § 1314]

Community History Reputation [Cal. Evid. Code § 1320]

Public Interest in Property [Cal. Evid. Code § 1321]

Boundary Reputation and Custom [Cal. Evid. Code § 1322]

Property Recital [Cal. Evid. Code § 1330]

Boundary Statement [Cal. Evid. Code § 1323]

Character/Reputation – Evidence of a person’s general reputation with reference to his character or a trait of his character at a relevant time in the community in which he then resided or in a group with which he then habitually associated is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule. [Cal. Evid. Code § 1324]

The California Supreme Court’s New Limitation On An Expert’s Ability To Rely On Hearsay Evidence

People v. Sanchez created new and significant challenges to dealing with hearsay evidence

As plaintiffs’ attorneys, we have many obstacles to overcome in collecting and presenting admissible evidence to a jury whether the evidence be in the form of physical evidence, witness testimony, or documentary evidence. When it comes to documentary evidence, the obstacles can be even higher to overcome given the rules of hearsay and the practicality of finding and deposing individuals who have stated opinions or facts contained within the documents.

For decades, plaintiff and defense attorneys alike, have been able to utilize expert testimony in order to present otherwise inadmissible hearsay evidence under the theory that the evidence was not in fact being presented to offer the truth of the matter contained within it, but was being offered only as the basis for the expert opinion. On June 30, 2016, the California Supreme Court published it’s ruling in the case of People v. Sanchez, (2016) 63 Cal.4th 665, which completely changed an attorney’s ability to present hearsay evidence through expert testimony and which has created new and significant challenges to dealing with hearsay evidence.

While Sanchez addresses several issues, including the Sixth Amendment Confrontation Clause and what constitutes “testimonial hearsay,” this article will focus on the new dynamic created by Sanchez in relation to California Evidence Code sections 801 and 802 and the practical challenges which now face plaintiffs’ attorneys in collecting and presenting admissible evidence.

Expert reliance on general knowledge hearsay vs. case-specific hearsay

Hearsay evidence is formally defined as “evidence of a statement that was made other than by a witness while testifying at the hearing and that is offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted.” (Cal. Evidence Code § 1200(a).) Dating back to common law and early case law, experts have been given significant latitude regarding what hearsay evidence they are allowed to testify about. Since that time Courts have separated the type of hearsay to which an expert is testifying into two categories: (1) background information and general knowledge, and (2) case-specific facts. While general knowledge hearsay may include mathematics, physics, medical testing or other accepted mediums of knowledge within a given experts profession, case-specific fact hearsay relates to particular events or participants to which the expert has no actual personal knowledge.

The rules of hearsay have traditionally not barred an expert from testifying regarding his general knowledge in his field of expertise, recognizing that experts frequently acquire their knowledge from hearsay and that to reject experts from testifying regarding their professional knowledge would ignore accepted professional methods and insist on impossible standards. The Sanchez ruling did not disrupt this standard as it states “our decision does not call into question the propriety of an expert’s testimony concerning background information regarding his knowledge and expertise and premises generally accepted in his field. Indeed, an expert’s background knowledge and experience is what distinguishes him from a lay witness, and, as noted, testimony regarding such background information has never been subject to exclusion as hearsay.” (Id. at 685.)

What the Sanchez court did change however, was the long accepted and evolved premise of how an expert could rely on, and testify, regarding case-specific facts contained in hearsay evidence. At common law, experts were typically precluded from testifying in regard to case-specific facts to which they had no knowledge. However, even prior to the California Evidence Code being enacted in 1965 there were already exceptions as to when an expert could relate otherwise inadmissible case-specific hearsay such as testimony regarding property valuation and medical diagnoses. The justification for these exceptions was very practical: (1) the expert routinely used the same kinds of hearsay in their conduct outside the court, (2) the expert’s expertise included experience in evaluating the trustworthiness of the hearsay sources, and (3) the desire to avoid needlessly complicating the process of proof. (Kaye et al., The New Wigmore: Expert Evidence (2d ed. 2011) § 4.5.1 p. 153-154.)

Case-specific hearsay: A thing of the past?

In 1965 when the California Legislature enacted the evidence code, the common law exceptions allowing experts to rely on and relate case-specific fact hearsay, and the reasoning behind said exceptions, were codified into Cal. Evidence Code § 801 and § 802. Cal. Evidence Code § 801(b) provides that an expert may provide an opinion “based on matter (including his special knowledge, skill, experience, training and education) perceived by or personally known to the witness or made known to him at or before the hearing, whether or not admissible, that is of a type that reasonably may be relied upon by an expert in forming an opinion upon which the subject to which his testimony relates, unless an expert is precluded by law in from using such matter as a basis for his opinion.” (italics added).

Similarly, Cal. Evidence Code § 802 allows an expert to “state on direct examination the reasons for his opinion and the matter (including, in the case of an expert, his special knowledge, skill, experience, training and education) upon which it is based, unless he is precluded by law from using such reasons or matter as a basis for his opinion.” Based on this codification, the ability of an expert to testify regarding case-specific facts had evolved. Under this precept, reliability of the information used by experts in forming their opinion is the key inquiry as to whether the expert testimony can be admitted. Additionally, the expert would be entitled to explain to the jury the matter upon which he relied, thus making otherwise inadmissible case-specific hearsay evidence admissible as the basis for the expert’s opinion, while remaining inadmissible to prove the truth of the matter asserted.

This is the paradigm that existed for two decades. As long as the evidence was reasonably reliable, ordinarily inadmissible case-specific hearsay evidence could be admitted as the basis for an expert’s opinion, assuming the expert relied on said evidence, regardless of whether the evidence was hearsay because it was not going to prove the truth of the matter asserted, it was merely going to show the basis for the expert opinion. Since the evidence is not going to prove the truth of the matter asserted, it is by definition not hearsay. In drafting the Code of Evidence, the California Legislature was obviously mindful of the practical applications of these rules. To disallow experts from explaining the basis for their opinions based on hearsay, despite the hearsay documents being reasonably reliable, creates an untenable court system and a near impossible burden in obtaining admissible evidence.

The above described rule regarding an expert’s ability to rely on and recite case-specific hearsay evidence was not simply allowed with free reign. As exemplified by the Supreme Court in People v. Coleman, (1985) 38 Cal.3d 69, the Court must still use its discretion in deciding what information is admissible based on weighing its probative value versus the potential prejudicial effect. (Cal. Evidence Code § 352.) In Coleman, the Supreme Court ruled that allowing the prosecution’s expert to recite hearsay letters of the Defendant’s deceased wife constituted reversible error in that, pursuant to Cal. Evidence Code § 352 the highly prejudicial effect of the letters far outweighed any probative value. The letters should therefore not have been allowed to be admitted as the basis for the prosecution expert’s opinion.

The Supreme Court subsequently created a two-step approach to balancing an expert’s need to consider extrajudicial matters, and a jury’s need for information sufficient to evaluate an expert opinion, so as not to conflict with the interest in avoiding substantive use of unreliable hearsay. The Court in People v. Montiel, (1993) 5 Cal.4th 877 ruled that “most often, hearsay problems will be cured by an instruction that matters admitted through an expert go only to the basis of his opinion and should not be considered for their truth.” Furthermore, “sometimes a limiting instruction will not be enough. In such cases, Cal. Evidence Code § 352 authorizes the court to exclude from an expert’s testimony any hearsay matter whose irrelevance, unreliability, or potential for prejudice outweighs its proper probative value.” (Id. at 919.) Simply put, the Montiel Court kept in effect the idea that experts may rely on, and relate to the jury, case-specific hearsay evidence as long as there is a limiting instruction to the jury that said evidence is not going to prove the truth of the matter asserted but instead is going only to show the basis for the expert opinion. The Montiel Court also specifically notes the need for courts to use the discretion afforded them by Cal. Evidence Code § 352 so as not to allow unreliable or prejudicial hearsay evidence to be admitted under the guise of the basis for an expert opinion.

It is the standard created by the Montiel Court which has governed litigators’ ability to admit case-specific hearsay evidence since 1993. Under this standard the admissibility of case-specific fact hearsay simply turned on whether a jury could properly follow the court’s limiting instruction regarding the nature of the hearsay evidence. If the limiting instruction is not sufficient, the Court has discretion to exclude the evidence under Cal. Evidence Code § 352. The evidence was not considered to be hearsay because it did not go to prove the truth of the matter, it only served as the basis for the expert’s opinion. The Montiel Court kept in effect the practical nature of allowing an expert to rely on and relate to the jury case-specific hearsay evidence as long as the evidence was reliable and not overly prejudicial. For over 20 more years, California litigators used experts to admit case-specific hearsay evidence as the basis for their opinion. As long as the evidence was reasonably reliable and not overly prejudicial, a limiting instruction was sufficient to allowing the evidence to be admitted regardless of whether it contained hearsay. This practical approach allowed litigators to admit hearsay evidence through their expert without having to break down the walls of hearsay, which in many cases would be impossible. In June 2016 the California Supreme Court decided to destroy this practical dynamic and ruled that whenever an expert relates case-specific fact hearsay they are in fact offering that hearsay content for its truth.

The new bright line rule on case-specific hearsay

The Sanchez case deals with several issues, including the Sixth Amendment confrontation clause and what constitutes “testimonial hearsay;” but the most astounding ruling that comes out of the Sanchez decision, and the one that is most relevant to any civil litigator is this: “If an expert testifies to case-specific out-of-court statements to explain the bases for his opinion, those statements are necessarily considered by the jury for their truth, thus rendering them hearsay. Like any other hearsay evidence, it must be admitted through an applicable hearsay exception. Alternatively the evidence can be admitted through an appropriate witness.” (Id. at 684.) The Sanchez Court specifically and purposely destroyed the pre-existing standard regarding what case-specific hearsay evidence an expert can rely on, stating that, “we conclude this paradigm (allowing an expert to rely on case-specific hearsay evidence with a limiting instruction that the evidence goes only to the basis of the expert opinion and not to the truth of the matter asserted) is no longer tenable because an expert’s testimony regarding the basis for an opinion must be considered for its truth by the jury.” (Id. at 679.)

The Sanchez court recites its reasoning for this new paradigm by stating that when an expert relies on hearsay to prove case-specific facts, considers the statements as true, and relates them to the jury as a reliable basis for the expert’s opinion, it cannot be logically asserted that the hearsay content is not being offered for its truth. (Id. at 682-683.) The expert is essentially telling the jury, “you should accept my opinion because it is reliable in light of these facts upon which I rely,” which means the expert is offering those facts for their truth. (Id. at 686.) While this reasoning may seem logical, it is certainly not practical, and does not comport with the Legislature’s 1965 enactment regarding evidence, nor the 50 years of case law which has followed.

The Sanchez Court makes sure that there is no confusion about the new rule they are putting forth. “In sum, we adopt the following rule: when any expert relates to the jury case-specific out-of-court statements, and treats the contents of those statements as true and accurate to support the expert’s opinion, the statements are hearsay. It cannot be logically maintained that the statements are not being admitted for their truth.” We disapprove our prior decisions1 concluding that an expert’s basis testimony is not being offered for the truth, or that a limiting instruction, coupled with the trial court’s evaluation of the potential prejudicial impact of the evidence under Cal. Evidence Code § 352 sufficiently addresses hearsay [and confrontation clause] concerns.” (Ibid.)

The Sanchez Court destroyed the ability to allow experts to rely on case-specific hearsay evidence unless it is subject to a hearsay exception. It purposefully and with specificity disapproved of prior California Supreme Court decisions which allowed such evidence to be relied upon and admitted. Going forward, litigators will need to be very aware of the Sanchez opinion and take proactive steps to ensure that important evidence is not deemed inadmissible hearsay, given that an expert’s reliance on said evidence will no longer be sufficient to have it admitted.

What are the practical ramifications of this decision?

The ramifications of this decision are significant. Whether talking about medical records, police reports, incident reports, or witness statements, it is commonly necessary to rely on hearsay evidence to some degree. Prior to Sanchez, as long as the source of the information was reliable, an expert could base their opinion on said evidence and the evidence could be admissible to show the basis for the expert’s opinion. That is no longer the case.

Pursuant to Sanchez, all case-specific hearsay evidence must now be subject to a hearsay exception in order to be admissible or relied on by an expert. It is well known that there are several hearsay exceptions to Cal. Evidence Code § 1200(a) including but not limited to business records, party admissions, prior consistent or inconsistent statements, dying declarations, non-party declarations against interest, statements regarding state of mind or physical condition, and past recollection recorded to name a few.2 It is now more important than ever to be familiar with these exceptions and know the full extent to which they will create an exception to hearsay. Evidence obviously comes in all shapes and forms and some hearsay issues will be more easily overcome then others based on how practical, or possible, it is to break down the wall of hearsay.

Medical records: An example

Take medical records as an example. Medical records may be the least affected by Sanchez given the hearsay exceptions available and the practicality of turning hearsay evidence into actual admissible evidence through witness testimony. Medical records themselves would typically be subject to a business record exception allowing portions of the record to be admissible. Statements made by the patient contained within the records can commonly be admitted through a state of mind or physical condition exception to hearsay. But what about the physician opinions and diagnoses contained within the medical records?

Prior to Sanchez, a proper expert could review the records and form their own opinion based on the diagnoses of other physicians. Those medical records, including the physicians’ opinions contained within them, would then be admissible in order to show the basis for that expert’s opinion. Not anymore. Now, if an attorney is interested in admitting a medical record which includes a physician’s opinion, that attorney will be required to depose that physician so as to make the opinion no longer hearsay. In some cases this may have occurred anyway, in others, this may be an incredible burden to overcome. At least when it comes to medical records, the physician is identified and it is at least feasible to find and depose them. Just hope they are still in the area.

Police reports

When it comes to police reports, the Sanchez burden can become almost impossible. With police reports, it usually comes down to one issue: witness statements. If the witness can be tracked down, then there is no issue. But what about when the witness is gone and cannot be found? Prior to Sanchez, an accident reconstructionist could use witness statements contained in the police report as a basis for their opinion. Therefore the witness statements could become admissible, not to prove the truth of the matter, but to show the basis for the expert opinion. Again, that is no longer the case. The reality of the matter is that litigators will have to invest significantly more time and money in order to find witnesses since their statements will now be otherwise inadmissible. Of course it is always best practice to have the witness testify in person, but that is not always possible. Prior to Sanchez the jury was at least still able to hear the witness statement, even if just through an expert.

The impossible burden: Prior similar occurrences

Where the Sanchez decision really hurts civil Plaintiffs’ attorneys is in regard to cases which involve, or necessitate, the showing of prior similar occurrences. While the above mentioned hypotheticals will affect defense attorneys as well, those same defense attorneys are ecstatic to see the Sanchez decision as it nearly destroys a Plaintiff’s ability to show prior similar occurrences.

Prior similar occurrences can commonly be some of the most important pieces of evidence a Plaintiff has in showing liability. Whether it is a case involving a dangerous animal who has a history of attacks, an employment discrimination case in which other employees were discriminated against as well, or a case involving a dangerous condition of property in which there have been other incidents, showing the existence of, and defendant’s knowledge of, prior similar incidents can often be the nail in the coffin, so to speak. If you have the evidence, it destroys a defendant’s ability to say “well, it never happened before.” In some cases, such as imposing liability onto a business for failure to prevent third party conduct, prior similar incidents are essentially an element of duty. Without being able to show prior incidents, a duty won’t even exist. So where does that leave Plaintiffs’ attorneys in the wake of Sanchez?

Statements contained in police reports, incident reports, or basically any written report will be considered hearsay even if portions of the report are admissible through a business records exception. Obtaining the reports themselves can be a challenge all in itself. Assuming you are able to obtain the reports, they can commonly be redacted so that the names of the complainants or witnesses are not obtainable. In context of an employment case, there may be several reports in which past or present employees reported misconduct. In a dangerous condition of property case, there may be several reports, police or otherwise, in which other individuals reported the exact same dangerous condition which is at issue in your case. So assuming you have the reports, what do you do with them now?

Prior to Sanchez, a proper expert could review the reports and base their opinions on the hearsay contained within them. A proper limiting instruction could be given and the jury would be able to evaluate the evidence. Now, Plaintiffs’ attorneys will be forced to depose each and every person who made a statement contained in a report in order to make the statement admissible. If the reports are redacted, you will first have to obtain some sort of protective order just to identify who you need to depose. The practical application of this idea is outrageous. Just contemplating the investment required to hunt down individuals who made statements years in the past is daunting, if not impossible.

What do we do now?

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Sanchez has changed decades of law in that any case-specific facts relied on by an expert are now ruled to go to the truth of the matter asserted, making them hearsay. In practical terms, this means that all hearsay statements and opinions must either be subject to a hearsay exception, or admitted through an appropriate witness. Hearsay statements can no longer be admitted as the basis for an expert opinion.

As litigators, all we can do is move forward using the laws that exist. As far as this issue goes, that means making sure you are aware of what evidence is hearsay, how many levels of hearsay exist, what portions of that evidence are subject to hearsay exceptions, and what steps you will need to take in order to overcome the enormous burden imposed by Sanchez. It also means that these issues will need to be addressed on the front end of case analysis since obtaining admissible evidence will take additional time and investment. There will be significant hurdles to overcome in obtaining evidence necessary to prosecute cases and no longer will we be able to fall back on having hearsay evidence admitted for the purpose of explaining the basis of expert opinion.

Endnote

1 People v. Bell, (2007) 40 Cal.4th 582; People v. Montiel, (1993) 5 Cal.4th 877; People v. Ainsworth, (1988) 45 Cal.3d 984; People v. Milner, (1988) 45 Cal.3d 227; People v. Coleman, (1985) 38 Cal.3d 69; People v. Gardeley, (1996)

14 Cal.4th 605; all specifically disapproved of.

2 Cal. Evidence Code § 1270-1272; § 1220-1227; § 1235, § 1236; § 1241, § 1230, § 1250, § 1237.

Learn More

Rules of Admissibility – Evidence Admissibility

Confrontation Clause – Sixth Amendment

Exceptions To The Hearsay Rule – Confronting Evidence

Rule 803. Exceptions to the Rule Against Hearsay

Primary tabs

The following are not excluded by the rule against hearsay, regardless of whether the declarant is available as a witness:

(1) Present Sense Impression. A statement describing or explaining an event or condition, made while or immediately after the declarant perceived it.

(2) Excited Utterance. A statement relating to a startling event or condition, made while the declarant was under the stress of excitement that it caused.

(3) Then-Existing Mental, Emotional, or Physical Condition. A statement of the declarant’s then-existing state of mind (such as motive, intent, or plan) or emotional, sensory, or physical condition (such as mental feeling, pain, or bodily health), but not including a statement of memory or belief to prove the fact remembered or believed unless it relates to the validity or terms of the declarant’s will.

(4) Statement Made for Medical Diagnosis or Treatment. A statement that:

(A) is made for — and is reasonably pertinent to — medical diagnosis or treatment; and

(B) describes medical history; past or present symptoms or sensations; their inception; or their general cause.

(5) Recorded Recollection. A record that:

(A) is on a matter the witness once knew about but now cannot recall well enough to testify fully and accurately;

(B) was made or adopted by the witness when the matter was fresh in the witness’s memory; and

(C) accurately reflects the witness’s knowledge.

If admitted, the record may be read into evidence but may be received as an exhibit only if offered by an adverse party.

(6) Records of a Regularly Conducted Activity. A record of an act, event, condition, opinion, or diagnosis if:

(A) the record was made at or near the time by — or from information transmitted by — someone with knowledge;

(B) the record was kept in the course of a regularly conducted activity of a business, organization, occupation, or calling, whether or not for profit;

(C) making the record was a regular practice of that activity;

(D) all these conditions are shown by the testimony of the custodian or another qualified witness, or by a certification that complies with Rule 902(11) or (12) or with a statute permitting certification; and

(E) neither the opponent does not show that the source of information nor or the method or circumstances of preparation indicate a lack of trustworthiness.

(7) Absence of a Record of a Regularly Conducted Activity. Evidence that a matter is not included in a record described in paragraph (6) if:

(A) the evidence is admitted to prove that the matter did not occur or exist;

(B) a record was regularly kept for a matter of that kind; and

(C) neither the opponent does not show that the possible source of the information nor or other circumstances indicate a lack of trustworthiness.

(8) Public Records. A record or statement of a public office if:

(A) it sets out:

(i) the office’s activities;

(ii) a matter observed while under a legal duty to report, but not including, in a criminal case, a matter observed by law-enforcement personnel; or

(iii) in a civil case or against the government in a criminal case, factual findings from a legally authorized investigation; and

(B) neither the opponent does not show that the source of information nor or other circumstances indicate a lack of trustworthiness.

(9) Public Records of Vital Statistics. A record of a birth, death, or marriage, if reported to a public office in accordance with a legal duty.

(10) Absence of a Public Record. Testimony — or a certification under Rule 902 — that a diligent search failed to disclose a public record or statement if:

(A) the testimony or certification is admitted to prove that

(i) the record or statement does not exist; or

(ii) a matter did not occur or exist, if a public office regularly kept a record or statement for a matter of that kind; and

(B) in a criminal case, a prosecutor who intends to offer a certification provides written notice of that intent at least 14 days before trial, and the defendant does not object in writing within 7 days of receiving the notice — unless the court sets a different time for the notice or the objection.

(11) Records of Religious Organizations Concerning Personal or Family History. A statement of birth, legitimacy, ancestry, marriage, divorce, death, relationship by blood or marriage, or similar facts of personal or family history, contained in a regularly kept record of a religious organization.

(12) Certificates of Marriage, Baptism, and Similar Ceremonies. A statement of fact contained in a certificate:

(A) made by a person who is authorized by a religious organization or by law to perform the act certified;

(B) attesting that the person performed a marriage or similar ceremony or administered a sacrament; and

(C) purporting to have been issued at the time of the act or within a reasonable time after it.

(13) Family Records. A statement of fact about personal or family history contained in a family record, such as a Bible, genealogy, chart, engraving on a ring, inscription on a portrait, or engraving on an urn or burial marker.

(14) Records of Documents That Affect an Interest in Property. The record of a document that purports to establish or affect an interest in property if:

(A) the record is admitted to prove the content of the original recorded document, along with its signing and its delivery by each person who purports to have signed it;

(B) the record is kept in a public office; and

(C) a statute authorizes recording documents of that kind in that office.

(15) Statements in Documents That Affect an Interest in Property. A statement contained in a document that purports to establish or affect an interest in property if the matter stated was relevant to the document’s purpose — unless later dealings with the property are inconsistent with the truth of the statement or the purport of the document.

(16) Statements in Ancient Documents. A statement in a document that was prepared before January 1, 1998, and whose authenticity is established.

(17) Market Reports and Similar Commercial Publications. Market quotations, lists, directories, or other compilations that are generally relied on by the public or by persons in particular occupations.

(18) Statements in Learned Treatises, Periodicals, or Pamphlets. A statement contained in a treatise, periodical, or pamphlet if:

(A) the statement is called to the attention of an expert witness on cross-examination or relied on by the expert on direct examination; and

(B) the publication is established as a reliable authority by the expert’s admission or testimony, by another expert’s testimony, or by judicial notice.

If admitted, the statement may be read into evidence but not received as an exhibit.

(19) Reputation Concerning Personal or Family History. A reputation among a person’s family by blood, adoption, or marriage — or among a person’s associates or in the community — concerning the person’s birth, adoption, legitimacy, ancestry, marriage, divorce, death, relationship by blood, adoption, or marriage, or similar facts of personal or family history.

(20) Reputation Concerning Boundaries or General History. A reputation in a community — arising before the controversy — concerning boundaries of land in the community or customs that affect the land, or concerning general historical events important to that community, state, or nation.

(21) Reputation Concerning Character. A reputation among a person’s associates or in the community concerning the person’s character.

(22) Judgment of a Previous Conviction. Evidence of a final judgment of conviction if:

(A) the judgment was entered after a trial or guilty plea, but not a nolo contendere plea;

(B) the conviction was for a crime punishable by death or by imprisonment for more than a year;

(C) the evidence is admitted to prove any fact essential to the judgment; and

(D) when offered by the prosecutor in a criminal case for a purpose other than impeachment, the judgment was against the defendant.

The pendency of an appeal may be shown but does not affect admissibility.

(23) Judgments Involving Personal, Family, or General History, or a Boundary. A judgment that is admitted to prove a matter of personal, family, or general history, or boundaries, if the matter:

(A) was essential to the judgment; and

(B) could be proved by evidence of reputation.

(24) [Other Exceptions .] [Transferred to Rule 807.]

Notes

(Pub. L. 93–595, §1, Jan. 2, 1975, 88 Stat. 1939; Pub. L. 94–149, §1(11), Dec. 12, 1975, 89 Stat. 805; Mar. 2, 1987, eff. Oct. 1, 1987; Apr. 11, 1997, eff. Dec. 1, 1997; Apr. 17, 2000, eff. Dec. 1, 2000; Apr. 26, 2011, eff. Dec. 1, 2011; Apr. 16, 2013, eff. Dec. 1, 2013; Apr. 25, 2014, eff. Dec. 1, 2014.)

Notes of Advisory Committee on Proposed Rules

The exceptions are phrased in terms of nonapplication of the hearsay rule, rather than in positive terms of admissibility, in order to repel any implication that other possible grounds for exclusion are eliminated from consideration.

The present rule proceeds upon the theory that under appropriate circumstances a hearsay statement may possess circumstantial guarantees of trustworthiness sufficient to justify nonproduction of the declarant in person at the trial even though he may be available. The theory finds vast support in the many exceptions to the hearsay rule developed by the common law in which unavailability of the declarant is not a relevant factor. The present rule is a synthesis of them, with revision where modern developments and conditions are believed to make that course appropriate.

In a hearsay situation, the declarant is, of course, a witness, and neither this rule nor Rule 804 dispenses with the requirement of firsthand knowledge. It may appear from his statement or be inferable from circumstances.

See Rule 602.

Exceptions (1) and (2). In considerable measure these two examples overlap, though based on somewhat different theories. The most significant practical difference will lie in the time lapse allowable between event and statement.

The underlying theory of Exception [paragraph] (1) is that substantial contemporaneity of event and statement negative the likelihood of deliberate of conscious misrepresentation. Moreover, if the witness is the declarant, he may be examined on the statement. If the witness is not the declarant, he may be examined as to the circumstances as an aid in evaluating the statement. Morgan, Basic Problems of Evidence 340–341 (1962).

The theory of Exception [paragraph] (2) is simply that circumstances may produce a condition of excitement which temporarily stills the capacity of reflection and produces utterances free of conscious fabrication. 6 Wigmore §1747, p. 135. Spontaneity is the key factor in each instance, though arrived at by somewhat different routes. Both are needed in order to avoid needless niggling.

While the theory of Exception [paragraph] (2) has been criticized on the ground that excitement impairs accuracy of observation as well as eliminating conscious fabrication, Hutchins and Slesinger, Some Observations on the Law of Evidence: Spontaneous Exclamations, 28 Colum.L.Rev. 432 (1928), it finds support in cases without number. See cases in 6 Wigmore §1750; Annot., 53 A.L.R.2d 1245 (statements as to cause of or responsibility for motor vehicle accident); Annot., 4 A.L.R.3d 149 (accusatory statements by homicide victims). Since unexciting events are less likely to evoke comment, decisions involving Exception [paragraph] (1) are far less numerous. Illustrative are Tampa Elec. Co. v. Getrost, 151 Fla. 558, 10 So.2d 83 (1942); Houston Oxygen Co. v. Davis, 139 Tex. 1, 161 S.W.2d 474 (1942); and cases cited in McCormick §273, p. 585, n. 4.

With respect to the time element, Exception [paragraph] (1) recognizes that in many, if not most, instances precise contemporaneity is not possible, and hence a slight lapse is allowable. Under Exception [paragraph] (2) the standard of measurement is the duration of the state of excitement. “How long can excitement prevail? Obviously there are no pat answers and the character of the transaction or event will largely determine the significance of the time factor.” Slough, Spontaneous Statements and State of Mind, 46 Iowa L.Rev. 224, 243 (1961); McCormick §272, p. 580.

Participation by the declarant is not required: a nonparticipant may be moved to describe what he perceives, and one may be startled by an event in which he is not an actor. Slough, supra; McCormick, supra; 6 Wigmore §1755; Annot., 78 A.L.R.2d 300.

Whether proof of the startling event may be made by the statement itself is largely an academic question, since in most cases there is present at least circumstantial evidence that something of a startling nature must have occurred. For cases in which the evidence consists of the condition of the declarant (injuries, state of shock), see Insurance Co. v. Mosely, 75 U.S. (8 Wall.), 397, 19 L.Ed. 437 (1869); Wheeler v. United States, 93 U.S.A.App. D.C. 159, 211 F.2d 19 (1953); cert. denied 347 U.S. 1019, 74 S.Ct. 876, 98 L.Ed. 1140; Wetherbee v. Safety Casualty Co., 219 F.2d 274 (5th Cir. 1955); Lampe v. United States, 97 U.S.App.D.C. 160, 229 F.2d 43 (1956). Nevertheless, on occasion the only evidence may be the content of the statement itself, and rulings that it may be sufficient are described as “increasing,” Slough, supra at 246, and as the “prevailing practice,” McCormick §272, p. 579. Illustrative are Armour & Co. v. Industrial Commission, 78 Colo. 569, 243 P. 546 (1926); Young v. Stewart, 191 N.C. 297, 131 S.E. 735 (1926). Moreover, under Rule 104(a) the judge is not limited by the hearsay rule in passing upon preliminary questions of fact.

Proof of declarant’s perception by his statement presents similar considerations when declarant is identified. People v. Poland, 22 Ill.2d 175, 174 N.E.2d 804 (1961). However, when declarant is an unidentified bystander, the cases indicate hesitancy in upholding the statement alone as sufficient, Garrett v. Howden, 73 N.M. 307, 387 P.2d 874 (1963); Beck v. Dye, 200 Wash. 1, 92 P.2d 1113 (1939), a result which would under appropriate circumstances be consistent with the rule.

Permissible subject matter of the statement is limited under Exception [paragraph] (1) to description or explanation of the event or condition, the assumption being that spontaneity, in the absence of a startling event, may extend no farther. In Exception [paragraph] (2), however, the statement need only “relate” to the startling event or condition, thus affording a broader scope of subject matter coverage. 6 Wigmore §§1750, 1754. See Sanitary Grocery Co. v. Snead, 67 App.D.C. 129, 90 F.2d 374 (1937), slip-and-fall case sustaining admissibility of clerk’s statement, “That has been on the floor for a couple of hours,” and Murphy Auto Parts Co., Inc. v. Ball, 101 U.S.App.D.C. 416, 249 F.2d 508 (1957), upholding admission, on issue of driver’s agency, of his statement that he had to call on a customer and was in a hurry to get home. Quick, Hearsay, Excitement, Necessity and the Uniform Rules: A Reappraisal of Rule 63(4), 6 Wayne L.Rev. 204, 206–209 (1960).

Similar provisions are found in Uniform Rule 63(4)(a) and (b); California Evidence Code §1240 (as to Exception (2) only); Kansas Code of Civil Procedure §60–460(d)(1) and (2); New Jersey Evidence Rule 63(4).

Exception (3) is essentially a specialized application of Exception [paragraph] (1), presented separately to enhance its usefulness and accessibility. See McCormick §§265, 268.

The exclusion of “statements of memory or belief to prove the fact remembered or believed” is necessary to avoid the virtual destruction of the hearsay rule which would otherwise result from allowing state of mind, provable by a hearsay statement, to serve as the basis for an inference of the happening of the event which produced the state of mind). Shepard v. United States, 290 U.S. 96, 54 S.Ct. 22, 78 L.Ed. 196 (1933); Maguire, The Hillmon Case—Thirty-three Years After, 38 Harv.L.Rev. 709, 719–731 (1925); Hinton, States of Mind and the Hearsay Rule, 1 U.Chi.L.Rev. 394, 421–423 (1934). The rule of Mutual Life Ins. Co. v. Hillman, 145 U.S. 285, 12 S.Ct. 909, 36 L.Ed. 706 (1892), allowing evidence of intention as tending to prove the doing of the act intended, is of course, left undisturbed.

The carving out, from the exclusion mentioned in the preceding paragraph, of declarations relating to the execution, revocation, identification, or terms of declarant’s will represents an ad hoc judgment which finds ample reinforcement in the decisions, resting on practical grounds of necessity and expediency rather than logic. McCormick §271, pp. 577–578; Annot., 34 A.L.R.2d 588, 62 A.L.R.2d 855. A similar recognition of the need for and practical value of this kind of evidence is found in California Evidence Code §1260.