peremptory writ of mandate (or mandamus)

A peremptory writ of mandate, or mandamus, is a judicial writ (i.e. order) to any governmental body, government official, or lower court requiring that the they perform an act or cease to act where the court finds that an official law, duty or judgment requires them to do so. That is, it is a type of mandamus writ, since the court is compelling another governmental body to do an act. However, it differs from an alternative writ of mandate in that a lower court or government body has already been established that the act that the court compels in the peremptory writ of mandate must be completed. The defendant has no further opportunities to contend their subjection to the writ; a peremptory writ of mandate is absolute and unqualified. For example, in Sholtz v. U.S., the Circuit Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit affirmed the issuance of a peremptory writ of mandate which required Florida state officials for the treasury department to pay a judgment, their liability therefor a lower court had established. As another example, the California Superior Court in California Building Industry Assoc’n v. State Water Resource Control Bd. issued a peremptory writ of mandate to compel the State Water Resource Control Board to halt the implementation of certain environmental standards where the invalidity of the standards has already been established. source

However, courts generally recognize the coercive nature of peremptory writs of mandate, and usually require that the defendant have notice of the petition of the writ and, if the case is of first instance, an opportunity to present their arguments. For example, California Code of Civil Procedure § 1088 requires that “[w]hen the application to the court is made without notice to the adverse party, and the writ is allowed, the alternative must be first issued; but if the application is upon due notice and the writ is allowed, the peremptory may be issued in the first instance.” Additionally, the California Court of Appeal in Campbell v. Superior Court illustrates an instance where defendants to a peremptory writ of mandate had the opportunity to present new evidence at a hearing to adjudge whether the writ should be issued. 2009 California Code of Civil Procedure – Section 1084-1097 :: Chapter 2. Writ Of Mandate

Master the distinctions between mandamus and mandate

Here we will discuss the difference and try to teach you.

Overview

The writ of mandate developed around 150 years ago to allow for judicial action when all else failed. Since then, its evolution has produced confused interpretations of the writ’s essential aspects. This article provides practical guidance for employing mandate and mandamus writs in California: which writ to bring, whether both would be appropriate and desirable, and how to anticipate the fact that a court always retains equitable discretion to deny a petition. This article concludes with a brief survey of structural changes that would do away with administrative mandamus and even the traditional writ of mandate altogether, save for the most extreme cases.

Analysis

Historical origins

The concept of mandamus traces back at least to 1615 with James Bagg’s Case,[1] and some scholars suggest its roots reach even further back to the Magna Carta and medieval times.[2] Originally it operated as a “prerogative writ,” brought exclusively by the British Crown.[3] Over time subjects gained the ability to use the writ, but the authority underpinning it still rested with the Crown.[4] Much like the contemporary writ, mandamus served to “compel public officials to perform their legal duties toward others.”[5] Historically, the terms mandate and mandamus have been used interchangeably, but in California practice there is a fundamental distinction between the two, which is explained in more detail below.

Mandamus was written into the earliest versions of California’s Code of Civil Procedure (later amended to the modern California usage mandate), and in the 1930s it proved to be the only viable solution for reviewing decisions of state and local agencies. As citizens of a newly chartered state, early California politicians were tasked with developing and implementing a new legal system. Elisha Crosby, the first Senate Judiciary Committee chair, argued vigorously for adopting a common law system rather than a civil law system.[6] He succeeded, and in 1851 the state legislature enacted the California Practice Act, which was based largely on the Field Code from New York and included provisions for writs of prohibition, mandamus, and certiorari.[7] In 1872 the Practice Act became the California Code of Civil Procedure, and its sections on extraordinary writs remain largely the same today.[8] These writs are denominated extraordinary relief because they are equitable last-resort remedies that are available only when no ordinary procedural vehicle is available.

The next major event in the writ’s evolution occurred with the emergence of the administrative state in the early 1900s, when the common law writ of mandate evolved to allow for judicial review of agency decisions. Applying this extraordinary relief to ordinary situations presented a judicial conundrum: by its nature mandate implicates the separation of powers. The essence of the writ is a judicial order compelling other officers to perform a duty, which presents the risk of overextending judicial branch authority. The next section explains how courts resolved that problem.

Evolution of administrative mandamus

While the traditional writ of mandate was adopted and implemented without issue in California courts, administrative mandamus developed in the mid-1930s as a last resort for reckoning with the growing administrative state. Faced with novel agencies that rapidly increased in number and powers, courts struggled with determining if and how they could review agency orders and decisions. There are three basic types of writs that a court could employ for that purpose: certiorari, which allows a court to review an inferior tribunal’s exercise of discretion; [9] prohibition, which allows a court to arrest the proceedings of an inferior tribunal;[10] and mandate or mandamus, which allows a court to compel an inferior tribunal or officer to perform some duty.[11] Early in this evolutionary process, the California Supreme Court rejected the writs of certiorari and prohibition in the administrative context.

In 1936, the California Supreme Court in Standard Oil Co. v. State Bd. of Equalization foreclosed the writ of certiorari as an option for dealing with agency decisions. The case involved the Board of Equalization and its decision to assess additional retail taxes against the petitioner.[12] The legislature had by statute provided for court review of certain board decisions, which effectively amounted to certiorari by another name. The state high court explained that the legislature cannot enlarge a court’s jurisdiction without constitutional authority.[13] Worse, courts could only entertain writs of certiorari for judicial decisions, and accepting certiorari review would effectively confer judicial functions on the administrative agency.[14] Since the legislature could neither expand the courts’ jurisdiction nor create a new judicial institution, the writ of certiorari was abandoned as a method for reviewing agency decisions.[15]

Just a year later, in Whitten v. State Bd. of Optometry the California Supreme Court barred using the writ of prohibition to review agency decisions, relying on separation of powers concerns.[16] As with certiorari, the court construed prohibition as applying only to the “restraint of a threatened exercise of the judicial power in excess of jurisdiction” and therefore inapplicable to the determination of a decidedly non-judicial agency.[17] Again, the legislature lacked the power to create new judicial institutions by statute.

After rejecting certiorari and prohibition, that left just mandamus. The court in Whitten suggested that mandamus could lie to review administrative decisions, and the California Supreme Court adopted that view just a few years later in Drummey v. State Bd. of Funeral Directors and Embalmers.[18] Drummey is important because it resolved the separation of powers problem: rather than being prevented by separation of powers concerns from reviewing agency decisions, that doctrine instead required judicial review. Agency decisions like this implicate constitutional property rights, and the separation of powers doctrine would be violated if courts could not review such deprivations: “[T]here is no warrant for the view that the judicial power of a competent court can be circumscribed by any legislative arrangement designed to give effect to administrative action going beyond the limits of constitutional authority.”[19] And having previously rejected certiorari and prohibition, “mandate is the only possible remedy available to those aggrieved by administrative rulings” of this nature.[20]

The legislature codifiedDrummey in 1945 with the Administrative Procedure Act. The APA adopted administrative mandamus as the appropriate avenue for reviewing agency decisions under Code of Civil Procedure section 1094.5.[21] The APA authorizes courts to issue extraordinary relief by writ of administrative mandamus to “any inferior tribunal, corporation, board, or person, to compel the performance of an act which the law specially enjoins, as a duty resulting from an office, trust, or station . . . .”[22] Any duty provided for by law — counting votes, levying taxes, suspending professional licenses — may be compelled through the writ under the right circumstances and according to the court’s discretion.

Mandamus and mandate are different

In this writ’s ancient beginnings mandamus and mandate had no distinction and were used interchangeably, but in current California practice they are distinct. Present-day writers often confuse the terms and use them synonymously; understandably so, given the historical evolution described above. But knowing what now distinguishes them is important. Mandate refers to the traditional writ, codified in Code of Civil Procedure sections 1085 and 1086, which require the absence of a “plain, speedy, and adequate remedy” as a basis for extraordinary relief.[23] Mandamus refers to the administrative writ, and it is almost always preceded by the modifier administrative. Administrative mandamus is codified in sections 1094.5 and 1094.6. One should avoid saying administrative mandate — that’s not a thing.

The distinction between traditional mandate and administrative mandamus stems from the distinction between legislative and adjudicatory decisions.[24] Legislative matters involve “the adoption of a broad, generally applicable rule of conduct on the basis of public policy,” while adjudicatory decisions “affect an individual as determined by facts peculiar to that individual.”[25] As with many legal binaries, the extremes are easily categorized, but the “middle ground . . . is not clear at all.”[26] In practice, the writs can be distinguished by the end goal. If one individual seeks to overturn one agency determination, use mandamus. If the petitioner hopes to change the way the agency makes a determination, use mandate. Finally, while most administrative mandamus cases must be filed first in the trial court, traditional mandate petitions may be brought in any court under its original jurisdiction. Note that writ petitions filed first in an appellate court likely will be rejected with directions to refile in the trial court — but if the facts are settled and an entire class of people is impacted then a higher court may be willing to intervene.[27]

Traditional mandate

Traditional mandate can touch any area wherein an individual has a clear and certain right and a public official or agency has a duty.[28] The writ may also be invoked when a party is unlawfully precluded from enjoying a right, including civil rights.[29] In determining whether an official has a particular duty, courts look to statutes, constitutional provisions, and other precedential decisions. There must be a present duty to perform; the writ cannot compel an official to perform a “future act” based on speculation that the official would refuse, nor an act “which it is too late to perform.”[30] That present duty must also be rooted in statutes as enacted, because statements of legislative intent do not create “any affirmative duty that is enforceable via writ of mandate.”[31] Unlike declaratory relief, which “simply pronounces the duty to perform,” mandate “commands performance.”[32] (The term mandate means “an authoritative order” or “formal command.”)[33]

Writ relief is discretionary

Because it is an extraordinary remedy, writ relief is at the court’s discretion. Courts, in their “wise discretion” and “to a considerable extent,” control mandate proceedings.[34] They can transform a petition for a writ of habeas corpus into a writ of mandate.[35] They can deny the writ even when the requirements seem to be fully satisfied.[36] Thus, although litigants are advised to only raise issues of law during mandate proceedings at the appellate level,[37] the courts may use their discretion when faced with questions of fact. Ultimately, “the petitioner’s right to relief is determinable by the facts as they existed at the time the petition was filed,”[38] but when and how those facts are determined is up to the court. One Court of Appeal justice described it: “We deny the vast majority of [writ] petitions we see and we rarely explain why.”[39]

Compelling Duty

Even when a duty exists, courts do not require public officials to attain perfect performance of those duties. And before mandating that a duty be performed, courts may consider the extent to which the party has performed or has attempted to perform the duty. [40] When courts do find a duty, they may not compel the performance of that duty or the exercise of discretion “in a particular manner”[41] unless there is but one “proper interpretation”[42] of how the duty can be performed. Similarly, the court can correct an officer’s “erroneous conception”[43] of his or her duties but cannot compel specific action beyond the correction. And courts cannot “command a person to perform an act beyond that enjoined by law upon him as a duty pertaining to his office or position.”[44]

Although these principles seem to restrict a court’s ability to control the action compelled through mandate, some courts have offered guideposts to direct the party performing the mandated duty. In Ley v. Dominguez the court reminded the city clerk that “[u]nder the law, he should exercise his powers and perform his duties in such a manner as will, whenever possible, protect rather than defeat the right of the people to exercise their referendary powers.”[45] In similar cases, courts have repeated this reminder that the clerk’s duty serves a right that is “precious to the people” when discussing how the clerk should go about performing that duty.[46]

Similarly, in Palmer v. Fox, the court ordered the performance of a duty with specific directions. The plaintiffs were denied a residential building permit because of racially discriminatory deed restrictions. The court not only mandated that defendants issue the permit, but also required that plaintiffs receive “prompt and courteous treatment by defendant.” [47] Directing official behavior beyond the official’s bare duties (do your job, and be nice about it) is a striking example of the broad powers of writ relief. Although courts cannot dictate how a duty should be performed, they may use writ relief to remind officials of the substantial rights that are served by their performance.

Establishing Facts

The traditional writ is the rare exception to the rule that appellate courts do not gather new evidence. Code of Civil Procedure section 1090 provides for a jury trial — on appeal — if a question of fact is raised during mandate proceedings.[48] At least once, a party in the California Supreme Court requested a factual hearing under this section.[49] Predictably, the court denied the request, stating that trial by jury is “singularly inappropriate for appellate courts.”[50] Rather than engage in fact-finding or dismiss the case, the court issued a writ of mandate tailored to avoid the disputed facts and address only the question of law.[51]

When disputed facts arise on appeal in a mandate proceeding, the appellate court likely will reverse and remand with instructions to the trial court. For example, in Stone v. Bd. of Directors of Pasadena, the court held that, if facts alleged were true, then the writ of mandate should issue.[52] But some “controverted issues which should be determined by the trial court” remained, and so the court could neither issue the writ itself nor order the trial court to do so.[53] Alternatively, when a mandate writ with disputed facts arrives at the appellate level, courts may dismiss the case and advise the litigants to begin again at the trial court.[54]

Administrative mandamus

Code of Civil Procedure sections 1094.5 and 1094.6 provide a complex pleading procedure for administrative mandamus. Nonetheless, areas of uncertainty and strange results persist. For example, section 1094.5 states that the reviewing court may apply either independent judgment or review for substantial evidence. If the court issues the writ, then the respondent may appeal the decision, and in that situation the appellate court treats the superior court as if it made a decision on the facts in the first instance.[55] Yet that was not the case — the trial court was acting as a reviewing court. The upshot is that the appellate court determines if the trial court abused its discretion, and the trial court in turn determined if the agency abused its discretion.[56] The central question of the case (the agency determination) moves to the periphery, and the lower court’s finding becomes the focus of the appellate review.

Another source of confusion is that some of the traditional writ (sections 1085 and 1086) procedures apply to section 1094.5 proceedings, raising questions as to whether other unwritten but persistent interpretations from traditional writ of mandate cases may apply. The exhaustion of remedies requirement is not mentioned in the text of section 1094.5. But it is required in traditional mandate, and exhaustion is often mentioned as a requirement for administrative mandamus.[57] This reflects the ancient nature of writ relief as an extraordinary remedy that will only lie where no other adequate remedy exists at law. The result: administrative mandamus should only lie where administrative direct review fails or does not exist.

Choosing between mandate and mandamus — or not

If a case satisfies the administrative mandamus requirements, then a petitioner must plead that writ.[58] Yet parties may also request section 1085 relief — in the same pleading — particularly if there is an argument that an agency decision will have an impact beyond the petitioner’s individual case.[59] The upshot is that a party might plead either mandate or mandamus, or request both in the same pleading. And courts have discretion to consider one writ as the other when faced with a pleading that erroneously pleads the incorrect writ.[60] But note that if a party chooses the wrong writ, on appeal the matter may be reversed and retried under the proper section, “even if nobody objected!”[61]

A court’s prerogative cuts both ways

The equitable discretion that permits courts to grant extraordinary relief is a two-edged sword. Even if a petitioner satisfies the requirements of writ of mandate or administrative mandamus, it is the court’s prerogative to draw upon their equitable discretion to deny relief.[62]

Because Code of Civil Procedure section 1085 gives no guidance on when writ relief is appropriate, courts have developed common law guidance. For example, in Bartholomae Oil Corp. v. Super. Ct. of San Francisco, the court explained that the writ “is not a matter of right but involves a consideration of its effect in promoting justice. Its issuance or refusal to a considerable extent lies within the sound discretion of the court.”[63] Similarly, if compelling some individual or agency to perform a duty would align with the letter of the law but insult its spirit, then the court has the equitable power to deny that relief.[64]

That common law guidance conflicts somewhat with section 1086, which in mandatory language states: “the writ must be issued in all cases where there is not a plain, speedy, and adequate remedy.”[65] These seemingly contradictory principles can be reconciled by examining the points at which courts exercise their discretion in deciding mandamus cases. For example, courts analyze whether “one has a substantial right to protect or enforce” and whether “this may be accomplished by such a writ.”[66] If a court finds that a right is too abstract, that other remedies are available, or that writ relief would be fruitless, the court is not required to issue the writ.[67] On the other hand, if a substantial right exists, that mandamus would prevent injustice, and that no other avenue for relief is available, then “it would be an abuse of discretion to refuse it.”[68] That equitable discretion even permits granting writ relief when no abuse of discretion occurred.[69]

The bottom line is that in deciding traditional writ of mandate proceedings, courts are held to much the same standard as the officials they are being asked to compel: they may exercise their discretion, unless there is only one way to do so. And the same equitable discretion applies to both traditional writ of mandate proceedings and to administrative mandamus. Despite the intricacies and complexities of section 1094.5, an imperfect petition may nonetheless be granted if it would achieve justice.

Finally, remember that writ relief will not permit a court to direct the legislature. Lawmaking is the opposite of a ministerial duty.[70] The legislature holds wide discretion in exercising its powers.[71] Take, for instance, coming together during a legislative session to enact laws.[72] Some commentators have suggested that the state legislature could be sued with a writ of mandate petition for its inaction around meeting remotely during the pandemic.[73] Courts generally refrain from telling lawmakers how to do their jobs, but they very well may have the authority to tell lawmakers to, at the very least, do their jobs.

Conclusion

Writ practice in California, and especially writ of mandate and administrative mandamus, is essential to developing state law, safeguarding the public interest, and vindicating individual rights. The California Supreme Court has issued writs of mandate against a wide range of executive officials, from city clerks all the way to the governor.[74] Laws may be invalidated when considered under a traditional writ of mandate petition.[75] And writs were at the procedural core of some of the most significant cases in California Supreme Court jurisprudence.[76]

Regardless of the future of administrative mandamus and traditional mandate, one thing remains certain: without a constitutional amendment cabining the original jurisdiction of the courts, some extraordinary relief procedure will persist. It releases the system’s inequitable pressure, providing a remedy for rights that have none. Because the power underlying the common law writs stems from the state constitution, the legislature cannot by statute unravel a century and a half of writ jurisprudence.

For the most extraordinary cases, where individuals or groups suffer a violation but enjoy no recourse in the usual course of law, extraordinary relief is the only option. These hard cases sometimes result in significant, groundbreaking decisions, and practitioners should know how to recognize the situations that call for mandate or mandamus. Success lies in the framing: the hard-and-fast elements of traditional mandate give way when equity demands it, and courts locate and employ their discretion accordingly.

—o0o—

Rachel Thompson is a research fellow at the California Constitution Center.

- Flint, The Evolving Standard for the Granting of Mandamus Relief in the Texas Supreme Court: One More Mile Marker down the Road of No Return (2007) 39 St. Mary’s L.J. 3. ↑

- Howell, An Historical Account of the Rise and Fall of Mandamus (1985) 15 Victoria U. Wellington L.Rev. 127, 129–32. ↑

- Id. at 128. ↑

- Ibid.↑

- Flint, supra note 1, at 18. It was brought to restore individuals to public office, command outgoing officers to deliver records to successors, and require courts to render final judgments. Id. at 16 n.34. ↑

- See Crosby, Memoirs of Elisha Oscar Crosby: Reminiscences of California and Guatemala from 1849 to 1864 (1945) 57–59. ↑

- Blume, Adoption in California of the Field Code of Civil Procedure: A Chapter in American Legal History (1966) 17 Hastings L.J. 701. ↑

- See Moskowitz, Spinning Gold into Straw: The Ordinary Use of the Extraordinary Writ of Mandamus to Review Quasilegislative Actions of California Administrative Agencies (1980) 20 Santa Clara L.Rev. 351, 365. ↑

- Cal. Civ. Proc. § 1068. ↑

- Id. § 1102. ↑

- Id. § 1085(a). ↑

- Standard Oil Co. v. State Bd. of Equalization (1936) at 559. ↑

- Ibid.↑

- Ibid.↑

- Id. at 565. This decision came as a surprise to attorneys and the lower courts, who had been using certiorari in this nature for years, and one historian claimed in 1964 that “probably no California case has caused more comment.” Clarkson, The History of the California Administrative Procedure Act (1964) 15 Hastings L.J. 237, 241. ↑

- Whitten v. State Bd. of Optometry (1937). ↑

- Id. at 445. ↑

- Drummey v. State Bd. of Funeral Directors and Embalmers (1939) at 77. ↑

- Id. at 85 (quoting St. Joseph Stock Yards Co. v. United States (1936) at 52); see also Laisne v. Cal. State Bd. of Optometry (1942) at 835 (“[A]ppellant would be deprived of his constitutional right unless he had a right to into a court of law and question the validity of [the agency’s] order.”). ↑

- Drummey at 83. ↑

- Clarkson, supra note 15. ↑

- Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 1085. ↑

- Witkin referred to this as a “mystical concept,” explaining that “the test of inadequacy of remedy is to a large extent an exercise of pure, uncontrolled discretion.” Witkin, Extraordinary Writ — Friend or Enemy? (1954) 29 J. State Bar Cal. 467, 471. ↑

- See Saleeby v. State Bar (1985) at 560. ↑

- Asimow, A Modern Judicial Review Statute to Replace Administrative Mandamus (Nov. 1993) in 27 Cal. Law Revision Com. Rep. 403, 414. ↑

- Ibid.↑

- See, e.g., Mooney v. Pickett (1971). ↑

- For instance, courts can compel issuing a building or use permit (Court House Plaza Co. v. Palo Alto (1981)); signing a bond or warrant (Paso Robles War Memorial Hospital Dist. v. Negley (1946)); compliance with a city charter (Squire v. San Francisco (1970)); and the publication of a parking district ordinance (Palm Springs v. Ringwald (1959)). Although not discussed at length here, writs of mandate may also be used as a means of judicial review of court decisions. For instance, a reviewing court can compel a lower tribunal to exercise jurisdiction (Golden Gate Tile Co. v. Super. Ct. of San Francisco (1911) 159 Cal. 474); to prevent improper discovery proceedings (Harabedian v. Super. Ct. of Los Angeles County (1961)); and to set a case for trial (Lindsay Strathmore Irrigation Dist. v. Super. Ct. of Tulare County (1932) 121 Cal.App. 606). SeeAppellate Review in California with the Extraordinary Writs (1948) 36 Calif. L.Rev. 75 for a more extensive discussion; see also Friedhofer, To Writ or Not To Writ? Taking the Drama Out of Deciding to File a Petition for Writ of Mandate (2005) League of California Cities — City Attorneys Spring Conference. ↑

- See, e.g., Piper v. Big Pine School Dist. (1924) 193 Cal. 664, 667 (holding it unconstitutional to deny a Native American child access to a public school on the basis of her race). ↑

- Treber v. Super. Ct. (1968) at 134. ↑

- Physicians Com. for Responsible Medicine v. Los Angeles Unified School Dist. (2019) at 189 (citing Common Cause v. Bd. of Supervisors (1989) at 444. ↑

- Berkeley Unified School Dist. v. City of Berkeley (1956) at 845. ↑

- Mandate, Merriam-Webster Dictionary (accessed Feb. 25, 2021); Mandamus, Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019) (tracing the term’s roots to the Latin for “we command”). ↑

- Wheelright v. County of Marin (1970) at 457. ↑

- Escamilla v. Cal. Dept. of Corrections & Rehabilitation (2006) at 419. ↑

- Fawkes v. City of Burbank (1922) 188 Cal. 399, 401. ↑

- See Fowler, Mandamus as an Original Proceeding in the California Appellate Courts (1963) 15 Hastings L.J. 177, 179. ↑

- American Distilling Co. v. City Council of Sausalito (1950) at 666; seeChrist v. Super. Ct. (1931) 211 Cal. 593, citing United States ex rel. International Contracting Co. v. Lamont (1894) 155 U.S. 303, 308. ↑

- Science Applications Internat. Corp. v. Super. Ct. (1995) at 1100. ↑

- See, e.g., Sutro Heights Land Co. v. Merced Irrigation Dist. (1931) 211 Cal. 670, 704–05 (“[D]efendant . . . is endeavoring to comply with the requirements of said statute. While it has not succeeded in discharging this duty to its fullest extent, it has done all that could reasonably be required of it with the money available for that purpose.”). ↑

- Common Cause v. Bd. of Supervisors (1989) at 442. ↑

- Anderson v. Phillips (1975) at 737. ↑

- Consolidated Printing & Publishing Co. v. Allen (1941) at 66. ↑

- Davis v. Porter (1885) 66 Cal. 658, 659. ↑

- Ley v. Dominguez (1931) 212 Cal. 587, 602. ↑

- Wheelright at 458–59; see alsoRakow v. Swain (1960) at 899; Reites v. Wilkerson (1950) at 829. ↑

- Palmer v. Fox (1953) at 455, 457. ↑

- Administrative mandamus, on the other hand, expressly states that the court sit without a jury. Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 1094.5(a). ↑

- Mooney at 682–83. ↑

- Id. at 683 (quotation and citation omitted). ↑

- Id. at 671. ↑

- Stone v. Bd. Of Directors of Pasadena (1941) at 754. ↑

- Ibid.↑

- Robinson v. Moran (1935) at 637 (dismissing the case without prejudice because “the several issues of fact presented in this proceeding may readily be determined in the superior court”); Boone v. Kingsbury (1928) 206 Cal. 148, 179, 194 (asserting that “the pleadings in this proceeding should have been settled and the disputed questions of fact found and determined by the superior court” and dismissing the petitions marred by disputed facts before rendering a final decision on the questions of law). ↑

- State Bd. of Medical Examiners (1948) at 316–18 (Traynor, J., dissenting). ↑

- See id.↑

- See Kumar v. Nat. Medical Enterprises, Inc. (1990) at 1055; see alsoBollengier v. Doctors Medical Center (1990). ↑

- Asimow, supra note 25, at 412. ↑

- See Conlan v. Bonta (2002) at 793–94. ↑

- See, e.g., Escamilla at 411 (concluding that the “petition for writ of habeas corpus should be treated as a petition for writ of mandamus” given the circumstances). ↑

- Asimow, supra note 25, at 410. ↑

- See Witkin, supra note 23, at 470 (“[T]his vital and expanding part of our review system is still clouded with a completely anachronistic theory of prerogative power. . . . [T]his results in denying a writ to a petitioner entitled to it under the existing precedents, or in issuing it to a petitioner not entitled to it under those precedents (and both have happened often) . . . .”). ↑

- Bartholomae Oil Corp. v. Super. Ct. (1941) at 730 (citations omitted). ↑

- Clough v. Baber (1940) at 53; see alsoWiedwald v. Dodson (1892) 95 Cal. 450, 453, 454 (holding that a statute, when strictly applied, would lead to the disincorporation of the town of San Pedro, which exceeded the true purpose of the statute). ↑

- SeeMay v. Bd. of Directors (1949) at 133–34 (holding that although petitioner could have gone to the superior court for relief, the Court would nonetheless mandate the local government to take action); Betty v. Super. Ct. (1941) at 622 (explaining that the possibility of a procedural appeal did not foreclose the Court issuing a writ of mandate). ↑

- Gay v. Torrance (1904) 145 Cal. 144, 147–48. ↑

- Id. at 147. ↑

- Id. at 148. ↑

- For example, in Curtin v. Dept. of Motor Vehicles (1981) the trial court granted petitioner’s writ although it found no error in the DMV’s suspension of the petitioner’s license. Curtin at 485 (“One’s entitlement to a writ of mandate is largely controlled by equitable principles. The same equitable principles will apply to administrative mandamus . . . .”). ↑

- See Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Assn. v. Padilla (2016) at 497–98 (“[T]he Legislature has the actual power to pass any act it pleases, subject only to those limits that may arise elsewhere in the state or federal Constitutions.”) ↑

- See, e.g., Legislature v. Deukmejian (1983) at 665–66 (“[T]he normal arguments in favor of the ‘passive virtues’ suggest that a court not adjudicate an issue until it is clearly required to do so.”). But some challenges are allowed pre-election. SeeSenate v. Jones (1999). ↑

- Cal. Const., Art. IV, sec. 3(a). ↑

- Carrillo & Duvernay, Why Isn’t California’s Legislature Meeting Remotely? (July 16, 2020) The Recorder. ↑

- See, e.g., Harpending v. Haight (1870) 39 Cal. 189, 213 (“Would the . . . great officers of State, by reason of their mere official rank, be beyond the reach of the process of the law in all cases, and not be compelled to perform any official act, no matter how distinctly enjoined upon them? . . . It seems to us that the assertion of such a doctrine would draw after it the most serious complication and confusion . . . and practically disrupt the whole fabric of government.”). ↑

- See, e.g., Perez v. Sharp (1948) (holding unconstitutional a law that forbade interracial marriages and mandating a county clerk to issue a marriage license to an interracial couple); Davis v. Municipal Court (1988) (reversing the Court of Appeal’s holding that a section of the penal code was unconstitutional on separation of powers principles and denying the petition for writ of mandate). ↑

- See, e.g., Lockyer v. City and County of San Francisco (2004); Strauss v. Horton (2009)

- source

Petition for a Writ of Mandate

The writ of mandate is a type of extraordinary writ in the U.S. state of California.[1][2] In California, certain writs are used by the superior courts, courts of appeal and the Supreme Court to command lower bodies, including both courts and administrative agencies, to do or not to do certain things. A writ of mandate may be granted by a court as an order to an inferior tribunal, corporation, board or person, both public and private.[3] Unlike the federal court system, where interlocutory appeals may be taken on a permissive basis and mandamus are usually used to contest recusal decisions, the writ of mandate in California is not restricted to purely ministerial tasks, but can be used to correct any legal error by the trial court. Nonetheless, ordinary writ relief in the Court of Appeal is rarely granted.

Writs are generally divided into two categories: the most common form of writ petition is ordinary mandate, which is a highly informal process mostly governed by advisory rules of court rather than by strict rules or statutes. A separate and much more formalized procedure called administrative mandate is used to review certain decisions by administrative agencies after adjudicatory hearings, and are distinguished from ordinary writ proceedings by the addition of a panoply of statutory requirements.[4] Despite the name, however, ordinary mandate encompasses a wider variety of administrative appeals than administrative mandate does, and an administrative mandate petition may allege ordinary mandate as another cause of action.[5] Many common writ petitions directed towards administrative bodies, such as actions to compel the disclosure of public records,[6] do not share the requirements of administrative mandate as there is no ‘adjudicatory hearing’.

A petition for a writ of mandate is a request for a court to review an agency’s decision and issue a writ directing the agency to set aside, reconsider, or take some other action. The terms “mandamus” and “mandate” are synonymous.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF MANDATE IN A MISDEMEANOR, INFRACTION, OR LIMITED CIVIL CASE

Information on Proceedings for Writs in the Appellate Division of the Superior Court

PETITIONS FOR WRIT OF MANDATE: WHEN TO FILE THEM AND WHAT TO SAY

PETITIONS FOR WRIT OF MANDATE Sample:

Petition for a Writ of Mandamus

Petition for a Writ of Mandamus – What is a writ of mandamus?

Here we will discuss the difference and try to teach you.

What is a writ of mandamus?

A writ of mandamus is a remedy that can be used to compel a lower court to perform an act that is ministerial in nature and that the court has a clear duty to do under law. When filing a petition for writ of mandamus, you must show that you have no other remedy available.

A writ of mandamus is different from an appeal. It asks the higher court to order the lower court to rule on some issue, but does not tell the judge how to rule. In an appeal, you would be asking the higher court to rule that the trial court made an error at the trial, such as improperly admitting evidence or giving incorrect jury instructions.

When Can a Writ of Mandamus Be Filed?

There is no time limit for filing a writ of mandamus. However, a petition for a writ of mandamus could be dismissed if you unreasonably delay in filing it.

When filing a petition for a writ of mandamus, you must comply with the requirements of Florida Rule of Appellate Procedure 9.100. You must show all of the following:

- That you have a clear right to relief

- That there is an undisputed duty on the lower court

- That there is no adequate remedy at law

- That you asked the lower court act first

You could file a petition for a writ of mandamus in these situations:

- To compel the lower court to rule on a motion, such as a post-conviction motion, that was filed a long time ago and no action was taken

- To compel a lower court to decide a case that was dismissed for lack of jurisdiction in error

- To compel the release of records after a public records request was made

- To compel a court-appointed lawyer or public defender to provide information to you

- To compel the Department of Corrections to award you credit for time served

Limitations on a Writ of Mandamus

A writ of mandamus can only be filed in limited circumstances. It cannot be used to:

- Seek review by an appellate court of an erroneous lower court decision

- Order the lower court to perform a discretionary act

- Control how a lower court acts

- Circumvent the restrictions in the Florida constitution on when a writ of mandamus can be used source

Petition for a Writ of Mandamus

Article 226 of the US Constitution

Article 226 of the US Constitution allows the High Court to enforce both Fundamental Rights and Legal Rights. It also allows the High Court to issue a writ exclusively in its own local jurisdiction. This limits the territorial authority of High Courts

Article 226 also states that the State shall assure assistance to the family and create mechanisms to suppress violence within the family.

To Learn More…. Read MORE Below and click the links Below

Abuse & Neglect – The Mandated Reporters (Police, D.A & Medical & the Bad Actors)

Mandated Reporter Laws – Nurses, District Attorney’s, and Police should listen up

If You Would Like to Learn More About: The California Mandated Reporting LawClick Here

To Read the Penal Code § 11164-11166 – Child Abuse or Neglect Reporting Act – California Penal Code 11164-11166Article 2.5. (CANRA) Click Here

Mandated Reporter formMandated ReporterFORM SS 8572.pdf – The Child Abuse

ALL POLICE CHIEFS, SHERIFFS AND COUNTY WELFARE DEPARTMENTS INFO BULLETIN:

Click Here Officers and DA’s for (Procedure to Follow)

It Only Takes a Minute to Make a Difference in the Life of a Child learn more below

You can learn more here California Child Abuse and Neglect Reporting Law its a PDF file

Learn More About True Threats Here below….

We also have the The Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) – 1st Amendment

CURRENT TEST = We also have the The ‘Brandenburg test’ for incitement to violence – 1st Amendment

We also have the The Incitement to Imminent Lawless Action Test– 1st Amendment

We also have the True Threats – Virginia v. Black is most comprehensive Supreme Court definition – 1st Amendment

We also have the Watts v. United States – True Threat Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Clear and Present Danger Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Gravity of the Evil Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Elonis v. United States (2015) – Threats – 1st Amendment

Learn More About What is Obscene…. be careful about education it may enlighten you

We also have the Miller v. California – 3 Prong Obscenity Test (Miller Test) – 1st Amendment

We also have the Obscenity and Pornography – 1st Amendment

Learn More About Police, The Government Officials and You….

$$ Retaliatory Arrests and Prosecution $$

Anti-SLAPP Law in California

Freedom of Assembly – Peaceful Assembly – 1st Amendment Right

We also have the Brayshaw v. City of Tallahassee – 1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Publius v. Boyer-Vine –1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, Florida (2018) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Nieves v. Bartlett (2019) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Hartman v. Moore (2006) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

We also have the Reichle v. Howards (2012) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

Freedom of the Press – Flyers, Newspaper, Leaflets, Peaceful Assembly – 1$t Amendment – Learn More Here

Vermont’s Top Court Weighs: Are KKK Fliers – 1st Amendment Protected Speech

We also have the Insulting letters to politician’s home are constitutionally protected, unless they are ‘true threats’ – Letters to Politicians Homes – 1st Amendment

We also have the First Amendment Encyclopedia very comprehensive – 1st Amendment

Dwayne Furlow v. Jon Belmar – Police Warrant – Immunity Fail – 4th, 5th, & 14th Amendment

ARE PEOPLE LYING ON YOU? CAN YOU PROVE IT? IF YES…. THEN YOU ARE IN LUCK!

Penal Code 118 PC – California Penalty of “Perjury” Law

Federal Perjury – Definition by Law

Penal Code 132 PC – Offering False Evidence

Penal Code 134 PC – Preparing False Evidence

Penal Code 118.1 PC – Police Officer$ Filing False Report$

Spencer v. Peters– Police Fabrication of Evidence – 14th Amendment

Penal Code 148.5 PC – Making a False Police Report in California

Penal Code 115 PC – Filing a False Document in California

Sanctions and Attorney Fee Recovery for Bad Actors

FAM § 3027.1 – Attorney’s Fees and Sanctions For False Child Abuse Allegations – Family Code 3027.1 – Click Here

FAM § 271 – Awarding Attorney Fees– Family Code 271 Family Court Sanction Click Here

Awarding Discovery Based Sanctions in Family Law Cases – Click Here

FAM § 2030 – Bringing Fairness & Fee Recovery – Click Here

Zamos v. Stroud – District Attorney Liable for Bad Faith Action – Click Here

Malicious Use of Vexatious Litigant – Vexatious Litigant Order Reversed

Mi$Conduct – Pro$ecutorial Mi$Conduct

Prosecutor$

Attorney Rule$ of Engagement – Government (A.K.A. THE PRO$UCTOR) and Public/Private Attorney

What is a Fiduciary Duty; Breach of Fiduciary Duty

The Attorney’s Sworn Oath

Malicious Prosecution / Prosecutorial Misconduct – Know What it is!

New Supreme Court Ruling – makes it easier to sue police

Possible courses of action Prosecutorial Misconduct

Misconduct by Judges & Prosecutor – Rules of Professional Conduct

Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

Standards on Prosecutorial Investigations – Prosecutorial Investigations

Information On Prosecutorial Discretion

Why Judges, District Attorneys or Attorneys Must Sometimes Recuse Themselves

Fighting Discovery Abuse in Litigation – Forensic & Investigative Accounting – Click Here

Criminal Motions § 1:9 – Motion for Recusal of Prosecutor

Pen. Code, § 1424 – Recusal of Prosecutor

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

National District Attorneys Association puts out its standards

National Prosecution Standards – NDD can be found here

The Ethical Obligations of Prosecutors in Cases Involving Postconviction Claims of Innocence

ABA – Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

Prosecutor’s Duty Duty to Disclose Exculpatory Evidence Fordham Law Review PDF

Chapter 14 Disclosure of Exculpatory and Impeachment Information PDF

Mi$Conduct – Judicial Mi$Conduct

Judge$

Prosecution Of Judges For Corrupt Practice$

Code of Conduct for United States Judge$

Disqualification of a Judge for Prejudice

Judicial Immunity from Civil and Criminal Liability

Recusal of Judge – CCP § 170.1 – Removal a Judge – How to Remove a Judge

l292 Disqualification of Judicial Officer – C.C.P. 170.6 Form

How to File a Complaint Against a Judge in California?

Commission on Judicial Performance – Judge Complaint Online Form

Why Judges, District Attorneys or Attorneys Must Sometimes Recuse Themselves

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

Obstruction of Justice and Abuse of Process

What Is Considered Obstruction of Justice in California?

Penal Code 135 PC – Destroying or Concealing Evidence

Penal Code 141 PC – Planting or Tampering with Evidence in California

Penal Code 142 PC – Peace Officer Refusing to Arrest or Receive Person Charged with Criminal Offense

Penal Code 182 PC – “Criminal Conspiracy” Laws & Penalties

Penal Code 664 PC – “Attempted Crimes” in California

Penal Code 32 PC – Accessory After the Fact

Penal Code 31 PC – Aiding and Abetting Laws

What is Abuse of Process? When the Government Fails Us

What’s the Difference between Abuse of Process, Malicious Prosecution and False Arrest?

Defeating Extortion and Abuse of Process in All Their Ugly Disguises

The Use and Abuse of Power by Prosecutors (Justice for All)

DUE PROCESS READS>>>>>>

Due Process vs Substantive Due Process learn more HERE

Understanding Due Process – This clause caused over 200 overturns in just DNA alone Click Here

Mathews v. Eldridge – Due Process – 5th & 14th Amendment Mathews Test – 3 Part Test– Amdt5.4.5.4.2 Mathews Test

“Unfriending” Evidence – 5th Amendment

At the Intersection of Technology and Law

We also have the Introducing TEXT & EMAIL Digital Evidence in California Courts – 1st Amendment

so if you are interested in learning about Introducing Digital Evidence in California State Courts

click here for SCOTUS rulings

Misconduct by Government Know Your Rights Click Here (must read!)

Under 42 U.S.C. $ection 1983 – Recoverable Damage$

42 U.S. Code § 1983 – Civil Action for Deprivation of Right$

18 U.S. Code § 242 – Deprivation of Right$ Under Color of Law

18 U.S. Code § 241 – Conspiracy against Right$

Section 1983 Lawsuit – How to Bring a Civil Rights Claim

Suing for Misconduct – Know More of Your Right$

Police Misconduct in California – How to Bring a Lawsuit

How to File a complaint of Police Misconduct? (Tort Claim Forms here as well)

Deprivation of Rights – Under Color of the Law

What is Sua Sponte and How is it Used in a California Court?

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors

and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

Anti-SLAPP Law in California

Freedom of Assembly – Peaceful Assembly – 1st Amendment Right

How to Recover “Punitive Damages” in a California Personal Injury Case

Pro Se Forms and Forms Information(Tort Claim Forms here as well)

What is Tort?

Tort Claims Form File Government Claim for Eligible Compensation

Complete and submit the Government Claim Form, including the required $25 filing fee or Fee Waiver Request, and supporting documents, to the GCP.

See Information Guides and Resources below for more information.

Tort Claims – Claim for Damage, Injury, or Death

Federal – Federal SF-95 Tort Claim Form Tort Claim online here or download it here or here from us

California – California Tort Claims Act – California Tort Claim Form Here or here from us

Complaint for Violation of Civil Rights (Non-Prisoner Complaint) and also UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT PDF

Taken from the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA Forms source

WRITS and WRIT Types in the United States

Appealing/Contesting Case/Order/Judgment/Charge/ Suppressing Evidence

First Things First: What Can Be Appealed and What it Takes to Get Started – Click Here

Options to Appealing– Fighting A Judgment Without Filing An Appeal Settlement Or Mediation

Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 1008 Motion to Reconsider

Penal Code 1385 – Dismissal of the Action for Want of Prosecution or Otherwise

Penal Code 1538.5 – Motion To Suppress Evidence in a California Criminal Case

CACI No. 1501 – Wrongful Use of Civil Proceedings

Penal Code “995 Motions” in California – Motion to Dismiss

WIC § 700.1 – If Court Grants Motion to Suppress as Evidence

Suppression Of Exculpatory Evidence / Presentation Of False Or Misleading Evidence – Click Here

Notice of Appeal — Felony (Defendant) (CR-120) 1237, 1237.5, 1538.5(m) – Click Here

California Motions in Limine – What is a Motion in Limine?

Petition for a Writ of Mandate or Writ of Mandamus (learn more…)

PARENT CASE LAW

RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR CHILDREN &

YOUR CONSTITUIONAL RIGHT$ + RULING$

YOU CANNOT GET BACK TIME BUT YOU CAN HIT THOSE IMMORAL NON CIVIC MINDED PUNKS WHERE THEY WILL FEEL YOU = THEIR BANK

Family Law Appeal – Learn about appealing a Family Court Decision Here

9.3 Section 1983 Claim Against Defendant as (Individuals) — 14th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

Amdt5.4.5.6.2 – Parental and Children’s Rights“> – 5th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

9.32 – Interference with Parent / Child Relationship – 14th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

California Civil Code Section 52.1

Interference with exercise or enjoyment of individual rights

Parent’s Rights & Children’s Bill of Rights

SCOTUS RULINGS FOR YOUR PARENT RIGHTS

SEARCH of our site for all articles relating for PARENTS RIGHTS Help!

Child’s Best Interest in Custody Cases

Are You From Out of State (California)? FL-105 GC-120(A)

Declaration Under Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction and Enforcement Act (UCCJEA)

Learn More:Family Law Appeal

Necessity Defense in Criminal Cases

Can You Transfer Your Case to Another County or State With Family Law? – Challenges to Jurisdiction

Venue in Family Law Proceedings

GRANDPARENT CASE LAW

Do Grandparents Have Visitation Rights? If there is an Established Relationship then Yes

Third “PRESUMED PARENT” Family Code 7612(C) – Requires Established Relationship Required

Cal State Bar PDF to read about Three Parent Law –

The State Bar of California family law news issue4 2017 vol. 39, no. 4.pdf

Distinguishing Request for Custody from Request for Visitation

Troxel v. Granville, 530 U.S. 57 (2000) – Grandparents – 14th Amendment

S.F. Human Servs. Agency v. Christine C. (In re Caden C.)

9.32 Particular Rights – Fourteenth Amendment – Interference with Parent / Child Relationship

Child’s Best Interest in Custody Cases

When is a Joinder in a Family Law Case Appropriate? – Reason for Joinder

Joinder In Family Law Cases – CRC Rule 5.24

GrandParents Rights To Visit

Family Law Packet OC Resource Center

Family Law Packet SB Resource Center

Motion to vacate an adverse judgment

Mandatory Joinder vs Permissive Joinder – Compulsory vs Dismissive Joinder

When is a Joinder in a Family Law Case Appropriate?

Kyle O. v. Donald R. (2000) 85 Cal.App.4th 848

Punsly v. Ho (2001) 87 Cal.App.4th 1099

Zauseta v. Zauseta (2002) 102 Cal.App.4th 1242

S.F. Human Servs. Agency v. Christine C. (In re Caden C.)

Retrieving Evidence / Internal Investigation Case

Conviction Integrity Unit (“CIU”) of the Orange County District Attorney OCDA – Click Here

Fighting Discovery Abuse in Litigation – Forensic & Investigative Accounting – Click Here

Orange County Data, BodyCam, Police Report, Incident Reports,

and all other available known requests for data below:

APPLICATION TO EXAMINE LOCAL ARREST RECORD UNDER CPC 13321 Click Here

Learn About Policy 814: Discovery Requests OCDA Office – Click Here

Request for Proof In-Custody Form Click Here

Request for Clearance Letter Form Click Here

Application to Obtain Copy of State Summary of Criminal HistoryForm Click Here

Request Authorization Form Release of Case Information – Click Here

Texts / Emails AS EVIDENCE: Authenticating Texts for California Courts

Can I Use Text Messages in My California Divorce?

Two-Steps And Voila: How To Authenticate Text Messages

How Your Texts Can Be Used As Evidence?

California Supreme Court Rules:

Text Messages Sent on Private Government Employees Lines

Subject to Open Records Requests

case law: City of San Jose v. Superior Court – Releasing Private Text/Phone Records of Government Employees

Public Records Practices After the San Jose Decision

The Decision Briefing Merits After the San Jose Decision

CPRA Public Records Act Data Request – Click Here

Here is the Public Records Service Act Portal for all of CALIFORNIA Click Here

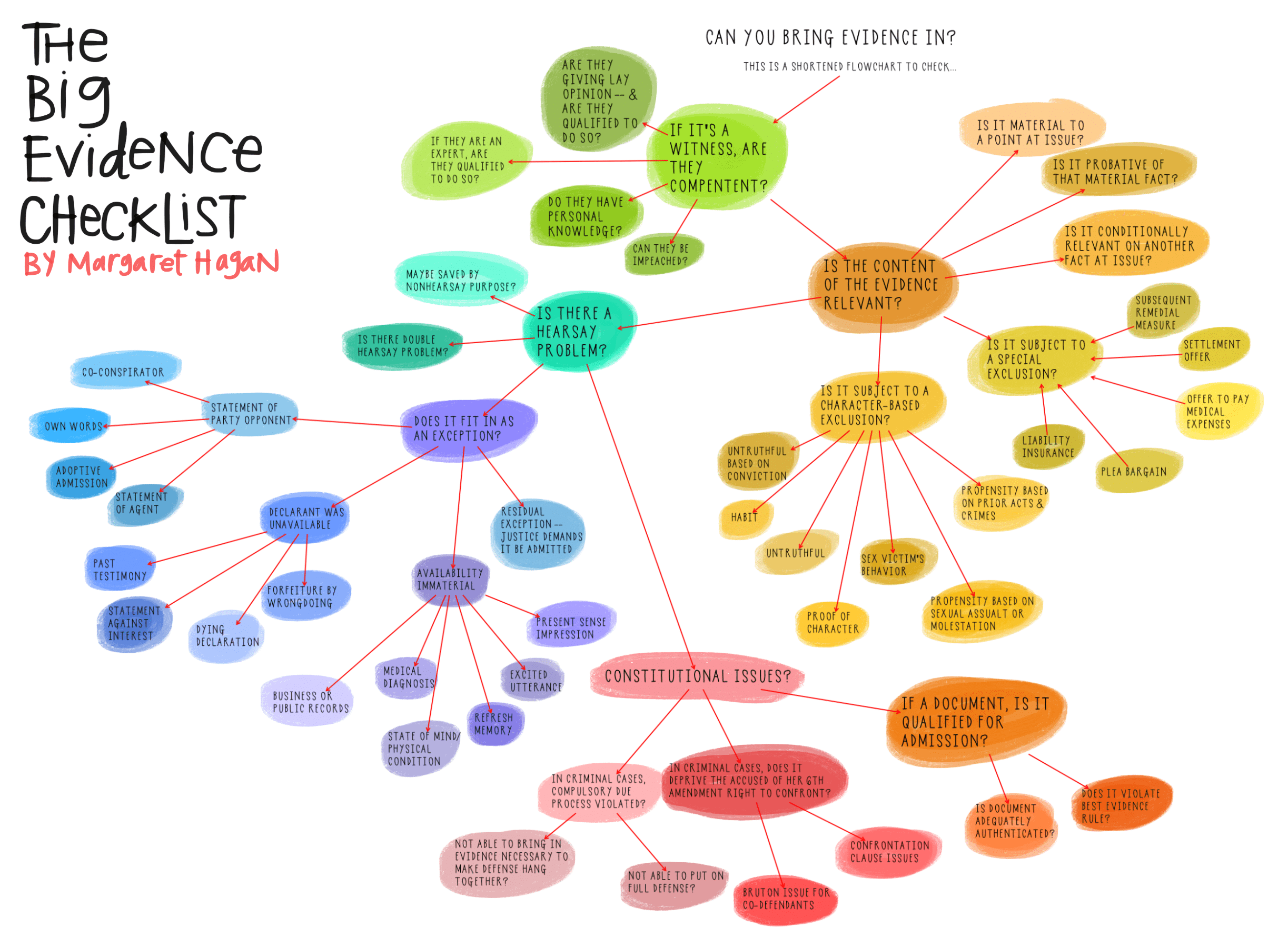

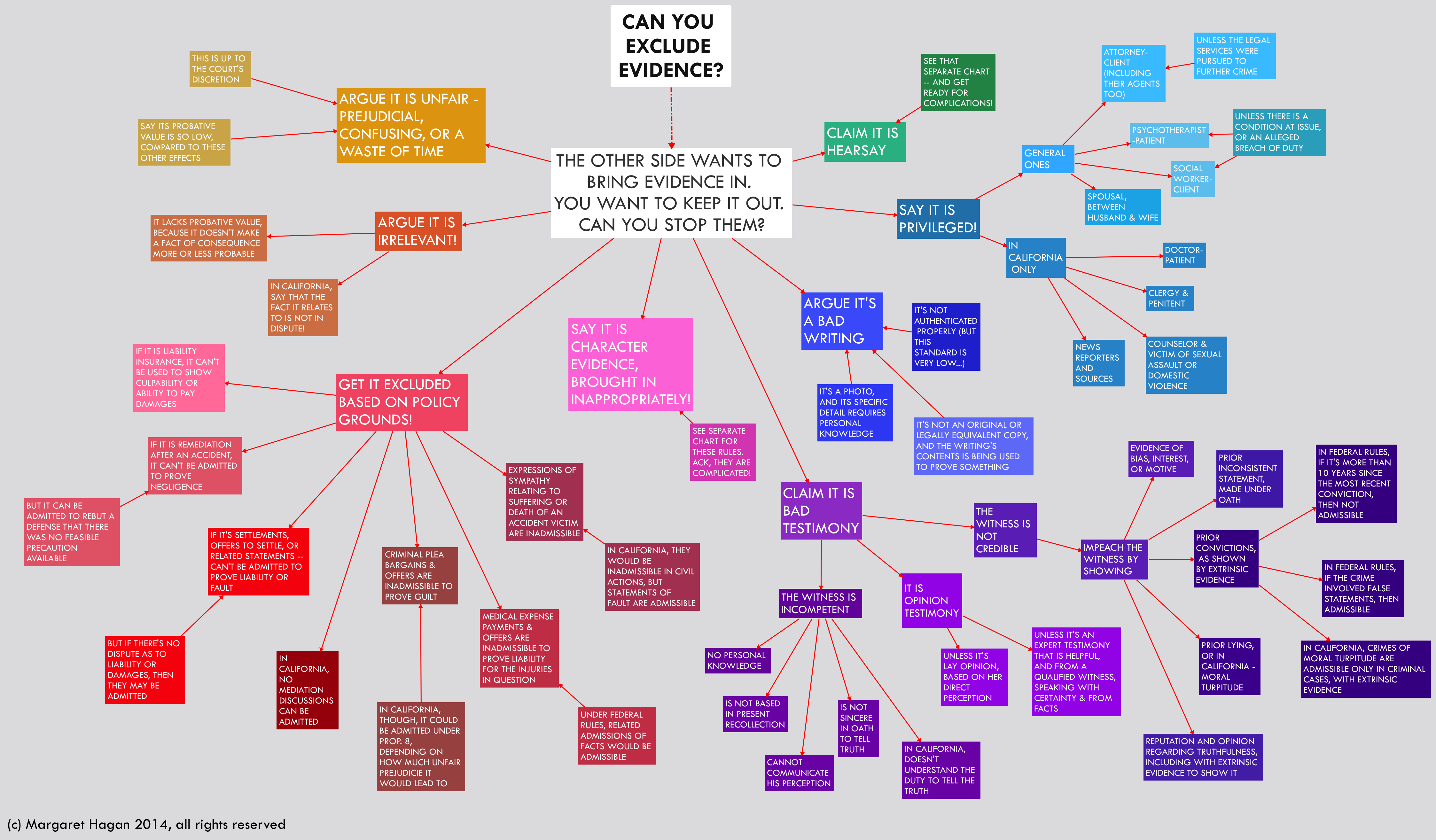

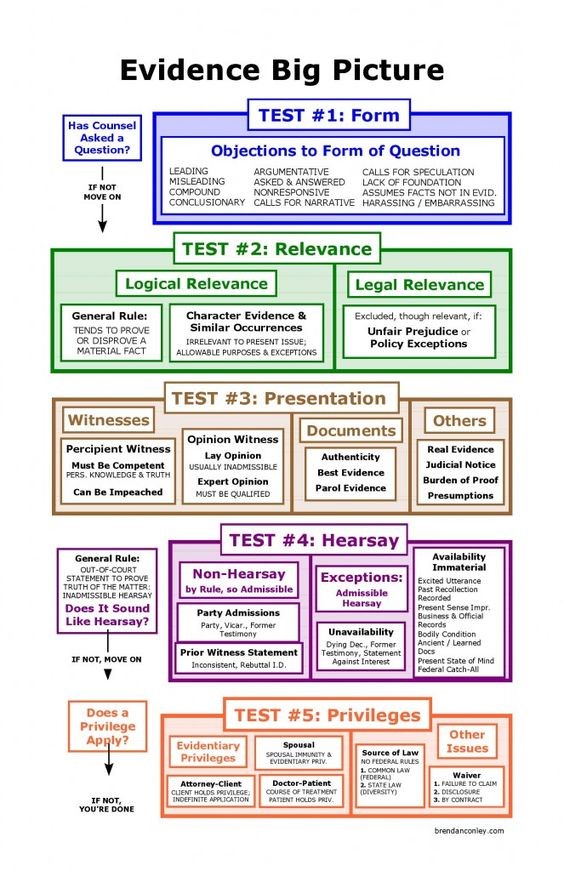

Rules of Admissibility – Evidence Admissibility

Confrontation Clause – Sixth Amendment

Exceptions To The Hearsay Rule – Confronting Evidence

Prosecutor’s Obligation to Disclose Exculpatory Evidence

Successful Brady/Napue Cases – Suppression of Evidence

Cases Remanded or Hearing Granted Based on Brady/Napue Claims

Unsuccessful But Instructive Brady/Napue Cases

ABA – Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

Frivolous, Meritless or Malicious Prosecution – fiduciary duty

Police BodyCam Footage Release

Electronic Audio Recording Request of OC Court Hearings

Cleaning Up Your Record

Penal Code 851.8 PC – Certificate of Factual Innocence in California

Petition to Seal and Destroy Adult Arrest Records – Download the PC 851.8 BCIA 8270 Form Here

SB 393: The Consumer Arrest Record Equity Act – 851.87 – 851.92 & 1000.4 – 11105 – CARE ACT

Expungement California – How to Clear Criminal Records Under Penal Code 1203.4 PC

How to Vacate a Criminal Conviction in California – Penal Code 1473.7 PC

Seal & Destroy a Criminal Record

Cleaning Up Your Criminal Record in California (focus OC County)

Governor Pardons – What Does A Governor’s Pardon Do

How to Get a Sentence Commuted (Executive Clemency) in California

How to Reduce a Felony to a Misdemeanor – Penal Code 17b PC Motion

Epic Criminal / Civil Right$ SCOTUS Help – Click Here

Epic Criminal / Civil Right$ SCOTUS Help – Click Here

Epic Parents SCOTUS Ruling – Parental Right$ Help – Click Here

Epic Parents SCOTUS Ruling – Parental Right$ Help – Click Here

Judge’s & Prosecutor’s Jurisdiction– SCOTUS RULINGS on

Judge’s & Prosecutor’s Jurisdiction– SCOTUS RULINGS on

Prosecutional Misconduct – SCOTUS Rulings re: Prosecutors

Prosecutional Misconduct – SCOTUS Rulings re: Prosecutors

Family Treatment Court Best Practice Standards

Download Here this Recommended Citation

Please take time to learn new UPCOMING

The PROPOSED Parental Rights Amendment

to the US CONSTITUTION Click Here to visit their site

The proposed Parental Rights Amendment will specifically add parental rights in the text of the U.S. Constitution, protecting these rights for both current and future generations.

The Parental Rights Amendment is currently in the U.S. Senate, and is being introduced in the U.S. House.