Newly Declassified Video Shows U.S. Killing of 10 Civilians in Drone Strike

The New York Times obtained footage of the botched strike in Kabul, whose victims included seven children, through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit.

Charlie Savage, Eric Schmitt, Azmat Khan, Evan Hill and

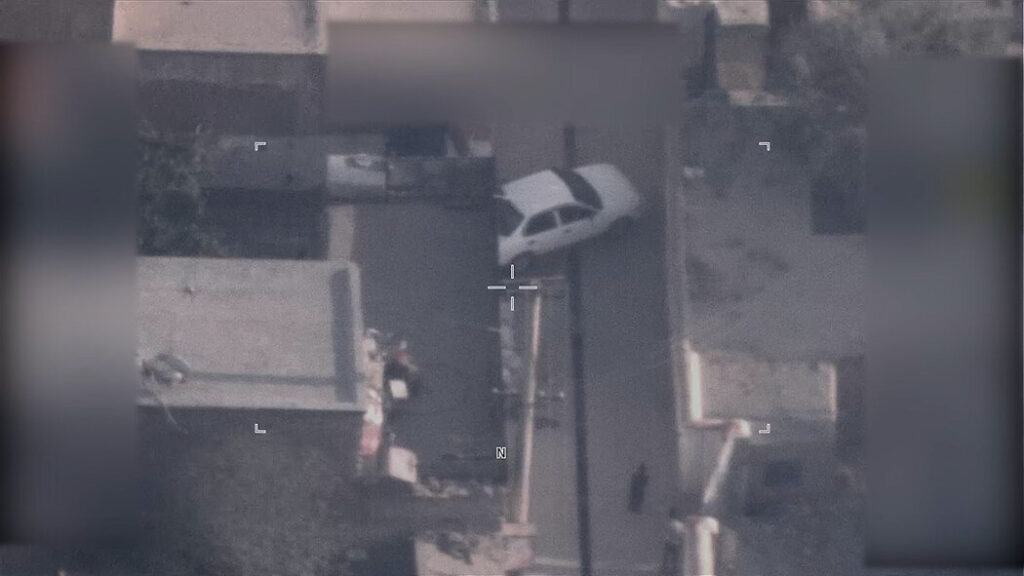

WASHINGTON — Newly declassified surveillance footage provides additional insights about the final minutes and aftermath of a botched U.S. drone strike last year in Kabul, Afghanistan, showing how the military made a life-or-death decision based on imagery that was fuzzy, hard to interpret in real time and prone to confirmation bias.

The strike on Aug. 29 killed 10 innocent people — including seven children — in a tragic blunder that punctuated the end of the 20-year war in Afghanistan.

The disclosure of the videos was a rare step by the U.S. military in any case of an airstrike that caused civilian casualties, and is the first time any footage from the Kabul strike has been seen publicly. The videos encompass about 25 minutes of silent footage from two drones — a military official said both were MQ-9 Reapers — showing the minutes before, during and after the strike.

The at-times blurry footage that operators were watching will continue to be scrutinized for new details about how the episode unfolded, while demonstrating the heightened risk of error that accompanies any decision to fire a missile in a densely populated neighborhood.

The military had been working that day under extreme pressure to head off another attack on troops and civilians in the middle of the chaotic withdrawal. It has said it believed it was tracking an ISIS-K terrorist who might imminently detonate a bomb near the Kabul airport. Three days earlier, a suicide bombing at the airport had killed at least 182 people, including 13 American troops.

The New York Times obtained the footage of the strike through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit against United States Central Command, which oversaw military operations in Afghanistan. The disclosure is likely to add fuel to a debate about the rules for airstrikes and protections for civilians in the era of drone warfare.

The videos — one of which is in grainy imagery, apparently from a camera designed to detect heat — show a car arriving at and backing into a courtyard on a residential street blocked by walls. Blurry figures are seen moving around the courtyard, and children are walking on the street outside the walls in the moments before a fireball from a Hellfire missile engulfs the interior. Neighbors can then be seen desperately dumping water onto the courtyard from rooftops.

The scenes unfolding on the video are murky. In retrospect, it is clear that the images were misinterpreted by those who decided to fire.

American operators on Aug. 29 had been tracking the driver of a white Toyota Corolla for about eight hours before targeting him in the mistaken belief that he was an ISIS-K member moving bombs. But the man was instead Zemari Ahmadi, a worker employed by Nutrition and Education International, a California-based aid organization.

More on U.S. Armed Forces

- Defense Bill: The House passed a $858 billion defense bill that would rescind the Pentagon’s mandate that troops receive the coronavirus vaccine and increase the defense budget $45 billion over the president’s request.

- Rules on Drone Strikes: President Biden signed a classified policy limiting counterterrorism drone strikes outside conventional war zones, tightening rules that President Donald J. Trump had loosened.

- Navy SEAL Recruitment: The high failure rate of the elite force’s selection course shunts hundreds of candidates into low-skilled jobs.

- Sexual Abuse: Pentagon officials acknowledged that they had failed to adequately supervise the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, after dozens of military veterans who taught in U.S. high schools were accused of sexually abusing their students.

In November, a Pentagon official said blurry images in the videos revealed the presence of at least one child in the blast zone about two minutes before the missile was launched, but stressed that spotting that was obvious only in hindsight and with “the luxury of time.”

The footage from one of the drones briefly shows what appears to be a blurry shorter figure in white next to a taller figure in black inside the courtyard as the car is backing in, about two and a half minutes before the explosion. Shuddering on the other drone’s footage, about 21 seconds before the explosion, suggests that might have been when it launched a missile.

Relatives have told The Times that some children rushed to greet Mr. Ahmadi — one getting into his car — when he got home to a compound where four interrelated families lived, and that others were fatally wounded in rooms alongside the courtyard.

The footage shows other figures of indeterminate height moving around the courtyard over several minutes as Mr. Ahmadi’s sedan backed into the compound, including one person opening the passenger door of the car just before the blast.

In the days after the strike, the military described a secondary explosion that it insisted supported the suspicion the car contained a bomb but later said was probably a propane tank. The footage shows a fireball from the blast, which expands about two seconds later, but it is tough to make out what is happening in the flare.

The heights of most figures inside the courtyard are difficult to determine because the footage was shot from overhead, making it harder to identify whether they might be children. The video with the better angle into the courtyard is in black-and-white and has lower resolution. The other video, which is in color, begins after the car was already backing in, but briefly shifts into black-and-white — apparently a thermal lens — at the moment of the strike.

Reached by phone, Emal Ahmadi, the brother of Mr. Ahmadi, whose daughter Malika was also killed in the strike, told The Times that he wanted to view the video himself, after having only heard descriptions from the military. “It will be difficult for me,” he said, “but I want to see it.”

Responding to a description, Hina Shamsi, an American Civil Liberties Union lawyer who is representing the families of the victims and Nutrition and Education International, which employed Mr. Ahmadi, said the footage highlighted “a painful, devastating loss of 10 deeply beloved people.”

Capt. Bill Urban, the spokesman for the U.S. Central Command, reiterated the Pentagon’s apology.

“While the strike was intended for what was believed to be an imminent threat to our troops at Hamid Karzai International Airport, none of the family members killed are now believed to have been connected to ISIS-K or threats to our troops,” he said. “We deeply regret the loss of life that resulted from this strike.”

The blurrier main video begins as the white car was approaching the courtyard, following the vehicle through several streets. It shows people moving in the courtyard several minutes before the strike, as the car stops and then backs in. A laser range-finder briefly appears about 70 seconds before the strike, and then returns and stays for the final half minute. Additional blurry figures are visible just before they are engulfed in flames.

The clearer video, which is mostly in color, starts as the car is backing in and reveals little about who was in the courtyard because of the angle from which it was shot. But it more plainly shows a figure opening the front-right door of the car just before the explosion, as well as children on the street outside the gated courtyard.

Both videos show people rushing to the site and throwing water onto the fire from nearby roofs. About 90 seconds after the strike, the higher-resolution color camera abruptly swivels away from the carnage to point at an unremarkable street scene nearby for the next five minutes.

The footage also underscores how drone operators may jump to the conclusion that any unknown people interacting with a terrorism suspect are likely fellow militants. In this case, even their suspicions about the suspect were wrong.

In November, the Air Force’s inspector general, Lt. Gen. Sami D. Said, released findings of his investigation into the strike, which found no violations of law and did not recommend any disciplinary action. The general blamed “confirmation bias” for warping operators’ interpretation of what they were seeing.

Officials have said that intelligence had indicated that an ISIS-K attacker would be driving a white Toyota Corolla, and that a certain building was a terrorist safe house. In fact, the building was the residence of the director of Mr. Ahmadi’s aid organization. But operators did not realize that error when Mr. Ahmadi headed to that building in his white Corolla — and from that premise over the next eight hours, they interpreted other mundane actions as threatening, too.

When someone in his car retrieved a black bag from that building, the operators interpreted the bag as an explosive since the airport bomber had used a black backpack; in fact, it was his boss’s laptop. When several people later placed canisters in the trunk of his car, the operators saw more bombs; in fact, the objects were most likely water containers. And when there appeared to be a secondary explosion after the missile blew up the car, they saw evidence of a bomb; in fact, the military later said, it was most likely a propane tank.

A trove of military reviews of reported civilian casualty incidents in the air war against ISIS in Iraq and Syria obtained by The Times revealed repeated instances of a similar confirmation bias.

“We know we need to improve situational awareness, communication between strike cells and nodes, and introduce a more robust process by which the analysis of intelligence can be scrutinized in real time,” Captain Urban told The Times in response to questions about confirmation bias.

The military initially announced that it had thwarted another planned attack outside the airport. But nearly everything that senior Pentagon officials claimed in the hours, days and weeks after the drone strike turned out to be wrong. A week after a Times video investigation showed that the man driving the car was Mr. Ahmadi, the Pentagon acknowledged that the strike had been a tragic mistake and no ISIS-K fighters had been killed.

How a U.S. Drone Strike Killed the Wrong Person

A week after a New York Times visual investigation, the U.S. military admitted to a tragic mistake in an Aug. 29 drone strike in Kabul that killed 10 civilians, including an aid worker and seven children.

-

[explosion] In one of the final acts of its 20-year war in Afghanistan, the United States fired a missile from a drone at a car in Kabul. It was parked in the courtyard of a home, and the explosion killed 10 people, including 43-year-old Zemari Ahmadi and seven children, according to his family. The Pentagon claimed that Ahmadi was a facilitator for the Islamic State, and that his car was packed with explosives, posing an imminent threat to U.S. troops guarding the evacuation at the Kabul airport. “The procedures were correctly followed, and it was a righteous strike.” What the military apparently didn’t know was that Ahmadi was a longtime aid worker, who colleagues and family members said spent the hours before he died running office errands, and ended his day by pulling up to his house. Soon after, his Toyota was hit with a 20-pound Hellfire missile. What was interpreted as the suspicious moves of a terrorist may have just been an average day in his life. And it’s possible that what the military saw Ahmadi loading into his car were water canisters he was bringing home to his family — not explosives. Using never-before seen security camera footage of Ahmadi, interviews with his family, co-workers and witnesses, we will piece together for the first time his movements in the hours before he was killed. Zemari Ahmadi was an electrical engineer by training. For 14 years, he had worked for the Kabul office of Nutrition and Education International. “NEI established a total of 11 soybean processing plants in Afghanistan.” It’s a California based NGO that fights malnutrition. On most days, he drove one of the company’s white Toyota corollas, taking his colleagues to and from work and distributing the NGO’s food to Afghans displaced by the war. Only three days before Ahmadi was killed, 13 U.S. troops and more than 170 Afghan civilians died in an Islamic State suicide attack at the airport. The military had given lower-level commanders the authority to order airstrikes earlier in the evacuation, and they were bracing for what they feared was another imminent attack. To reconstruct Ahmadi’s movements on Aug. 29, in the hours before he was killed, The Times pieced together the security camera footage from his office, with interviews with more than a dozen of Ahmadi’s colleagues and family members. Ahmadi appears to have left his home around 9 a.m. He then picked up a colleague and his boss’s laptop near his house. It’s around this time that the U.S. military claimed it observed a white sedan leaving an alleged Islamic State safehouse, around five kilometers northwest of the airport. That’s why the U.S. military said they tracked Ahmadi’s Corolla that day. They also said they intercepted communications from the safehouse, instructing the car to make several stops. But every colleague who rode with Ahmadi that day said what the military interpreted as a series of suspicious moves was just a typical day in his life. After Ahmadi picked up another colleague, the three stopped to get breakfast, and at 9:35 a.m., they arrived at the N.G.O.’s office. Later that morning, Ahmadi drove some of his co-workers to a Taliban-occupied police station to get permission for future food distribution at a new displacement camp. At around 2 p.m., Ahmadi and his colleagues returned to the office. The security camera footage we obtained from the office is crucial to understanding what happens next. The camera’s timestamp is off, but we went to the office and verified the time. We also matched an exact scene from the footage with a timestamp satellite image to confirm it was accurate. A 2:35 p.m., Ahmadi pulls out a hose, and then he and a co-worker fill empty containers with water. Earlier that morning, we saw Ahmadi bring these same empty plastic containers to the office. There was a water shortage in his neighborhood, his family said, so he regularly brought water home from the office. At around 3:38 p.m., a colleague moves Ahmadi’s car further into the driveway. A senior U.S. official told us that at roughly the same time, the military saw Ahmadi’s car pull into an unknown compound 8 to 12 kilometers southwest of the airport. That overlaps with the location of the NGO’s office, which we believe is what the military called an unknown compound. With the workday ending, an employee switched off the office generator and the feed from the camera ends. We don’t have footage of the moments that followed. But it’s at this time, the military said that its drone feed showed four men gingerly loading wrapped packages into the car. Officials said they couldn’t tell what was inside them. This footage from earlier in the day shows what the men said they were carrying — their laptops one in a plastic shopping bag. And the only things in the trunk, Ahmadi’s co-workers said, were the water containers. Ahmadi dropped each one of them off, then drove to his home in a dense neighborhood near the airport. He backed into the home’s small courtyard. Children surrounded the car, according to his brother. A U.S. official said the military feared the car would leave again, and go into an even more crowded street or to the airport itself. The drone operators, who hadn’t been watching Ahmadi’s home at all that day, quickly scanned the courtyard and said they saw only one adult male talking to the driver and no children. They decided this was the moment to strike. A U.S. official told us that the strike on Ahmadi’s car was conducted by an MQ-9 Reaper drone that fired a single Hellfire missile with a 20-pound warhead. We found remnants of the missile, which experts said matched a Hellfire at the scene of the attack. In the days after the attack, the Pentagon repeatedly claimed that the missile strike set off other explosions, and that these likely killed the civilians in the courtyard. “Significant secondary explosions from the targeted vehicle indicated the presence of a substantial amount of explosive material.” “Because there were secondary explosions, there’s a reasonable conclusion to be made that there was explosives in that vehicle.” But a senior military official later told us that it was only possible to probable that explosives in the car caused another blast. We gathered photos and videos of the scene taken by journalists and visited the courtyard multiple times. We shared the evidence with three weapons experts who said the damage was consistent with the impact of a Hellfire missile. They pointed to the small crater beneath Ahmadi’s car and the damage from the metal fragments of the warhead. This plastic melted as a result of a car fire triggered by the missile strike. All three experts also pointed out what was missing: any evidence of the large secondary explosions described by the Pentagon. No collapsed or blown-out walls, including next to the trunk with the alleged explosives. No sign that a second car parked in the courtyard was overturned by a large blast. No destroyed vegetation. All of this matches what eyewitnesses told us, that a single missile exploded and triggered a large fire. There is one final detail visible in the wreckage: containers identical to the ones that Ahmadi and his colleague filled with water and loaded into his trunk before heading home. Even though the military said the drone team watched the car for eight hours that day, a senior official also said they weren’t aware of any water containers. The Pentagon has not provided The Times with evidence of explosives in Ahmadi’s vehicle or shared what they say is the intelligence that linked him to the Islamic State. But the morning after the U.S. killed Ahmadi, the Islamic State did launch rockets at the airport from a residential area Ahmadi had driven through the previous day. And the vehicle they used … … was a white Toyota. The U.S. military has so far acknowledged only three civilian deaths from its strike, and says there is an investigation underway. They have also admitted to knowing nothing about Ahmadi before killing him, leading them to interpret the work of an engineer at a U.S. NGO as that of an Islamic State terrorist. Four days before Ahmadi was killed, his employer had applied for his family to receive refugee resettlement in the United States. At the time of the strike, they were still awaiting approval. Looking to the U.S. for protection, they instead became some of the last victims in America’s longest war. “Hi, I’m Evan, one of the producers on this story. Our latest visual investigation began with word on social media of an explosion near Kabul airport. It turned out that this was a U.S. drone strike, one of the final acts in the 20-year war in Afghanistan. Our goal was to fill in the gaps in the Pentagon’s version of events. We analyzed exclusive security camera footage, and combined it with eyewitness accounts and expert analysis of the strike aftermath. You can see more of our investigations by signing up for our newsletter.”

Still, the Pentagon had resisted making the videos public, deeming them classified and exempt from disclosure. But it told a judge this month that officials were “engaged in high-level consultations regarding whether any portions can be declassified and publicly released” in response to The Times’s lawsuit. Under a court order, the government had a deadline of Tuesday to make a final determination.

The Times sued for a copy of the surveillance footage starting five minutes before the drone began tracking the white car to five minutes after the missile strike, which would amount to about eight hours. It is not clear what happened to the remaining footage, a question that may be the subject of further litigation.

The botched strike has helped spur a closer look at the military’s targeting rules and the adequacy of protections for civilians in war zones after two decades in which airstrikes from remote-operated drones became routine — leading to recurring incidents in which civilian bystanders are killed.

Credit…Jim Huylebroek for The New York Times

Under the law of war, it can be legal to carry out strikes that kill some civilians, as long as they were not the intended target and as long as the anticipated collateral damage is deemed to be necessary and proportionate to the military aim. But the Defense Department has long said that it tries to minimize civilian casualties.

Still, with United States ground forces no longer in theaters like Afghanistan and Somalia and drawing down from Syria and Iraq, strikes on traditional or “hot” battlefields may be less frequent compared with so-called over-the-horizon counterterrorism strikes in poorly governed places where there are no American troops to defend on the ground — but where good intelligence may be even harder to come by.

The Biden administration has also been working on a new policy governing drone warfare away from traditional battlefields. That process was meant to last only a few months, but after a year of drafts, deliberations and high-level meetings, it remains uncompleted.

The U.S. government has offered to resettle the relatives of the victims — and employees of the aid organization — and to make unspecified condolence payments to the families, Ms. Shamsi said, but they have received no compensation and are instead focused on leaving Afghanistan.

“We aren’t even discussing compensation because our clients’ safety comes first,” she said.

Ainara Tiefenthäler contributed reporting. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/19/us/politics/afghanistan-drone-strike-video.html/