Due Process vs Substantive Due Process

Due Process 5th & 14th Amendment

Substantive due process is a principle in United States constitutional law that allows courts to establish and protect certain fundamental rights from government interference, even if only procedural protections are present or the rights are unenumerated elsewhere in the U.S. Constitution.

Introduction

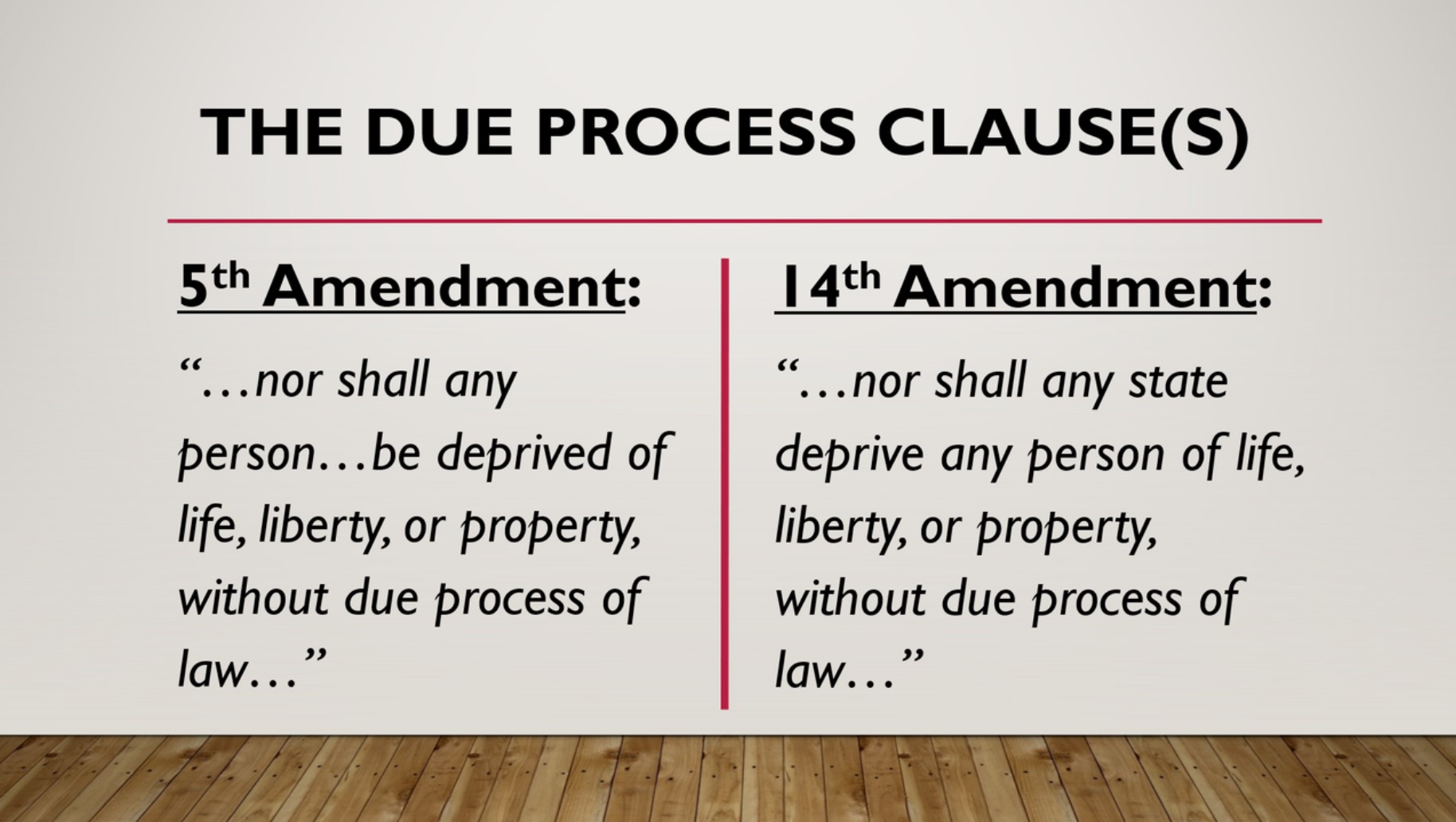

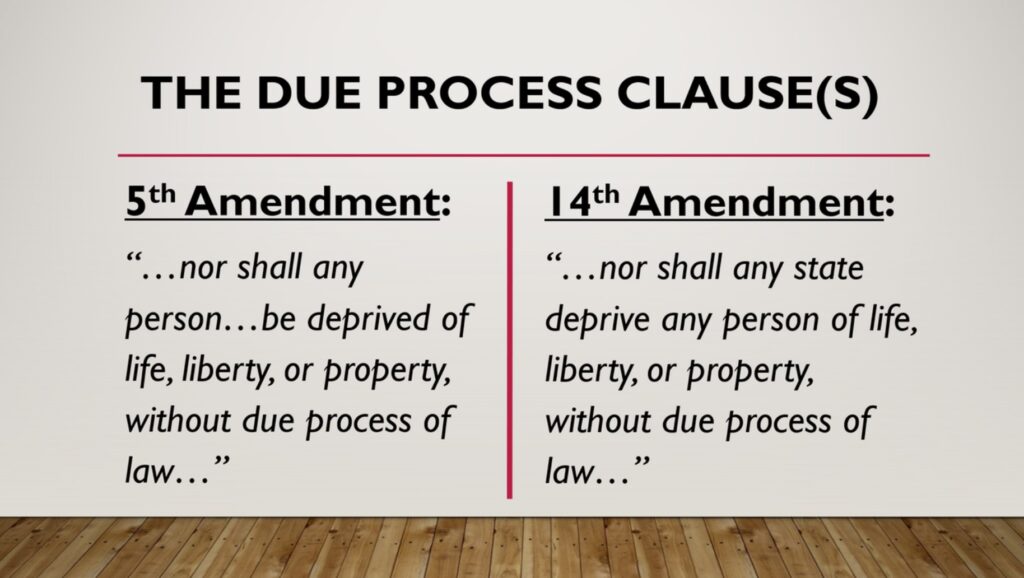

The Constitution states only one command twice. The Fifth Amendment says to the federal government that no one shall be “deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, uses the same eleven words, called the Due Process Clause, to describe a legal obligation of all states. These words have as their central promise an assurance that all levels of American government must operate within the law (“legality”) and provide fair procedures. Most of this article concerns that promise. We should briefly note, however, three other uses that these words have had in American constitutional law.

Incorporation

The Fifth Amendment’s reference to “due process” is only one of many promises of protection the Bill of Rights gives citizens against the federal government. Originally these promises had no application at all against the states; the Bill of Rights was interpreted to only apply against the federal government, given the debates surrounding its enactment and the language used elsewhere in the Constitution to limit State power. (see Barron v City of Baltimore (1833)). However, this changed after the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment and a string of Supreme Court cases that began applying the same limitations on the states as the Bill of Rights. Initially, the Supreme Court only piecemeal added Bill of Rights

protections against the States, such as in Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Company v. City of Chicago (1897) when the court incorporated the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause into the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court saw these protections as a function of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment only, not because the Fourteenth Amendment made the Bill of Rights apply against the states. Later, in the middle of the Twentieth Century, a series of Supreme Court decisions found that the Due Process Clause “incorporated” most of the important elements of the Bill of Rights and made them applicable to the states. If a Bill of Rights guarantee is “incorporated” in the “due process” requirement of the Fourteenth Amendment, state and federal obligations are exactly the same. For more information on the incorporation doctrine, please see this Wex Article on the Incorporation Doctrine.

Substantive due process

The words “due process” suggest a concern with procedure rather than substance, and that is how many—such as Justice Clarence Thomas, who wrote “the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause is not a secret repository of substantive guarantees against unfairness”—understand the Due Process Clause. However, others believe that the Due Process Clause does include protections of substantive due process—such as Justice Stephen J. Field, who, in a dissenting opinion to the Slaughterhouse Cases wrote that “the Due Process Clause protected individuals from state legislation that infringed upon their ‘privileges and immunities’ under the federal Constitution” (see this Library of Congress Article: https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/magna-carta-muse-and-mentor/due-process-of-law.html)

Substantive due process has been interpreted to include things such as the right to work in an ordinary kind of job, marry, and to raise one’s children as a parent. In Lochner v New York (1905), the Supreme Court found unconstitutional a New York law regulating the working hours of bakers, ruling that the public benefit of the law was not enough to justify the substantive due process right of the bakers to work under their own terms. Substantive due process is still invoked in cases today, but not without criticism (See this Stanford Law Review article to see substantive due process as applied to contemporary issues).

The promise of legality and fair procedure

Historically, the clause reflects the Magna Carta of Great Britain, King John’s thirteenth century promise to his noblemen that he would act only in accordance with law (“legality”) and that all would receive the ordinary processes (procedures) of law. It also echoes Great Britain’s Seventeenth Century struggles for political and legal regularity, and the American colonies’ strong insistence during the pre-Revolutionary period on observance of regular legal order. The requirement that the government function in accordance with law is, in itself, ample basis for understanding the stress given these words. A commitment to legality is at the heart of all advanced legal systems, and the Due Process Clause is often thought to embody that commitment.

The clause also promises that before depriving a citizen of life, liberty or property, the government must follow fair procedures. Thus, it is not always enough for the government just to act in accordance with whatever law there may happen to be. Citizens may also be entitled to have the government observe or offer fair procedures, whether or not those procedures have been provided for in the law on the basis of which it is acting. Action denying the process that is “due” would be unconstitutional. Suppose, for example, state law gives students a right to a public education, but doesn’t say anything about discipline. Before the state could take that right away from a student, by expelling her for misbehavior, it would have to provide fair procedures, i.e. “due process.”

How can we know whether process is due (what counts as a “deprivation” of “life, liberty or property”), when it is due, and what procedures have to be followed (what process is “due” in those cases)? If “due process” refers chiefly to procedural subjects, it says very little about these questions. Courts unwilling to accept legislative judgments have to find answers somewhere else. The Supreme Court’s struggles over how to find these answers echo its interpretational controversies over the years, and reflect the changes in the general nature of the relationship between citizens and government.

In the Nineteenth Century government was relatively simple, and its actions relatively limited. Most of the time it sought to deprive its citizens of life, liberty or property it did so through criminal law, for which the Bill of Rights explicitly stated quite a few procedures that had to be followed (like the right to a jury trial) — rights that were well understood by lawyers and courts operating in the long traditions of English common law. Occasionally it might act in other ways, for example in assessing taxes. In Bi-Metallic Investment Co. v. State Board of Equalization (1915), the Supreme Court held that only politics (the citizen’s “power, immediate or remote, over those who make the rule”) controlled the state’s action setting the level of taxes; but if the dispute was about a taxpayer’s individual liability, not a general question, the taxpayer had a right to some kind of a hearing (“the right to support his allegations by arguments however brief and, if need be, by proof however informal”). This left the state a lot of room to say what procedures it would provide, but did not permit it to deny them altogether.

Distinguishing due process

Bi-Metallic established one important distinction: the Constitution does not require “due process” for establishing laws; the provision applies when the state acts against individuals “in each case upon individual grounds” — when some characteristic unique to the citizen is involved. Of course there may be a lot of citizens affected; the issue is whether assessing the effect depends “in each case upon individual grounds.” Thus, the due process clause doesn’t govern how a state sets the rules for student discipline in its high schools; but it does govern how that state applies those rules to individual students who are thought to have violated them — even if in some cases (say, cheating on a state-wide examination) a large number of students were allegedly involved.

Even when an individual is unmistakably acted against on individual grounds, there can be a question whether the state has “deprive[d]” her of “life, liberty or property.” The first thing to notice here is that there must be state action. Accordingly, the Due Process Clause would not apply to a private school taking discipline against one of its students (although that school will probably want to follow similar principles for other reasons).

Whether state action against an individual was a deprivation of life, liberty or property was initially resolved by a distinction between “rights” and “privileges.” Process was due if rights were involved, but the state could act as it pleased in relation to privileges. But as modern society developed, it became harder to tell the two apart (ex: whether driver’s licenses, government jobs, and welfare enrollment are “rights” or a “privilege.” An initial reaction to the increasing dependence of citizens on their government was to look at the seriousness of the impact of government action on an individual, without asking about the nature of the relationship affected. Process was due before the government could take an action that affected a citizen in a grave way.

In the early 1970s, however, many scholars accepted that “life, liberty or property” was directly affected by state action, and wanted these concepts to be broadly interpreted. Two Supreme Court cases involved teachers at state colleges whose contracts of employment had not been renewed as they expected, because of some political positions they had taken. Were they entitled to a hearing before they could be treated in this way? Previously, a state job was a “privilege” and the answer to this question was an emphatic “No!” Now, the Court decided that whether either of the two teachers had “property” would depend in each instance on whether persons in their position, under state law, held some form of tenure. One teacher had just been on a short term contract; because he served “at will” — without any state law claim or expectation to continuation — he had no “entitlement” once his contract expired. The other teacher worked under a longer-term arrangement that school officials seemed to have encouraged him to regard as a continuing one. This could create an “entitlement,” the Court said; the expectation need not be based on a statute, and an established custom of treating instructors who had taught for X years as having tenure could be shown. While, thus, some law-based relationship or expectation of continuation had to be shown before a federal court would say that process was “due,” constitutional “property” was no longer just what the common law called “property”; it now included any legal relationship with the state that state law regarded as in some sense an “entitlement” of the citizen. Licenses, government jobs protected by civil service, or places on the welfare rolls were all defined by state laws as relations the citizen was entitled to keep until there was some reason to take them away, and therefore process was due before they could be taken away. This restated the formal “right/privilege” idea, but did so in a way that recognized the new dependency of citizens on relations with government, the “new property” as one scholar influentially called it.

When process is due

In its early decisions, the Supreme Court seemed to indicate that when only property rights were at stake (and particularly if there was some demonstrable urgency for public action) necessary hearings could be postponed to follow provisional, even irreversible, government action. This presumption changed in 1970 with the decision in Goldberg v. Kelly, a case arising out of a state-administered welfare program. The Court found that before a state terminates a welfare recipient’s benefits, the state must provide a full hearing before a hearing officer, finding that the Due Process Clause required such a hearing.

What procedures are due

Just as cases have interpreted when to apply due process, others have determined the sorts of procedures which are constitutionally due. This is a question that has to be answered for criminal trials (where the Bill of Rights provides many explicit answers), for civil trials (where the long history of English practice provides some landmarks), and for administrative proceedings, which did not appear on the legal landscape until a century or so after the Due Process Clause was first adopted. Because there are the fewest landmarks, the administrative cases present the hardest issues, and these are the ones we will discuss.

The Goldberg Court answered this question by holding that the state must provide a hearing before an impartial judicial officer, the right to an attorney’s help, the right to present evidence and argument orally, the chance to examine all materials that would be relied on or to confront and cross-examine adverse witnesses, or a decision limited to the record thus made and explained in an opinion. The Court’s basis for this elaborate holding seems to have some roots in the incorporation doctrine.

Many argued that the Goldberg standards were too broad, and in subsequent years, the Supreme Court adopted a more discriminating approach. Process was “due” to the student suspended for ten days, as to the doctor deprived of his license to practice medicine or the person accused of being a security risk; yet the difference in seriousness of the outcomes, of the charges, and of the institutions involved made it clear there could be no list of procedures that were always “due.” What the Constitution required would inevitably be dependent on the situation. What process is “due” is a question to which there cannot be a single answer.

A successor case to Goldberg, Mathews v. Eldridge, tried instead to define a method by which due process questions could be successfully presented by lawyers and answered by courts. The approach it defined has remained the Court’s preferred method for resolving questions over what process is due. Mathews attempted to define how judges should ask about constitutionally required procedures. The Court said three factors had to be analyzed:

- First, the private interest that will be affected by the official action;

- Second, the risk of an erroneous deprivation of such interest through the procedures used, and the probable value, if any, of additional or substitute procedural safeguards;

- Finally, the Government’s interest, including the function involved and the fiscal and administrative burdens that the additional or substitute procedural requirement would entail.

Using these factors, the Court first found the private interest here less significant than in Goldberg. A person who is arguably disabled but provisionally denied disability benefits, it said, is more likely to be able to find other “potential sources of temporary income” than a person who is arguably impoverished but provisionally denied welfare assistance. Respecting the second, it found the risk of error in using written procedures for the initial judgment to be low, and unlikely to be significantly reduced by adding oral or confrontational procedures of the Goldberg variety. It reasoned that disputes over eligibility for disability insurance typically concern one’s medical condition, which could be decided, at least provisionally, on the basis of documentary submissions; it was impressed that Eldridge had full access to the agency’s files, and the opportunity to submit in writing any further material he wished. Finally, the Court now attached more importance than the Goldberg Court had to the government’s claims for efficiency. In particular, the Court assumed (as the Goldberg Court had not) that “resources available for any particular program of social welfare are not unlimited.” Thus additional administrative costs for suspension hearings and payments while those hearings were awaiting resolution to persons ultimately found undeserving of benefits would subtract from the amounts available to pay benefits for those undoubtedly eligible to participate in the program. The Court also gave some weight to the “good-faith judgments” of the plan administrators what appropriate consideration of the claims of applicants would entail.

Matthews thus reorients the inquiry in a number of important respects. First, it emphasizes the variability of procedural requirements. Rather than create a standard list of procedures that constitute the procedure that is “due,” the opinion emphasizes that each setting or program invites its own assessment. The only general statement that can be made is that persons holding interests protected by the due process clause are entitled to “some kind of hearing.” Just what the elements of that hearing might be, however, depends on the concrete circumstances of the particular program at issue. Second, that assessment is to be made concretely and holistically. It is not a matter of approving this or that particular element of a procedural matrix in isolation, but of assessing the suitability of the ensemble in context.

Third, and particularly important in its implications for litigation seeking procedural change, the assessment is to be made at the level of program operation, rather than in terms of the particular needs of the particular litigants involved in the matter before the Court. Cases that are pressed to appellate courts often are characterized by individual facts that make an unusually strong appeal for proceduralization. Indeed, one can often say that they are chosen for that appeal by the lawyers, when the lawsuit is supported by one of the many American organizations that seeks to use the courts to help establish their view of sound social policy. Finally, and to similar effect, the second of the stated tests places on the party challenging the existing procedures the burden not only of demonstrating their insufficiency, but also of showing that some specific substitute or additional procedure will work a concrete improvement justifying its additional cost. Thus, it is inadequate merely to criticize. The litigant claiming procedural insufficiency must be prepared with a substitute program that can itself be justified.

The Mathews approach is most successful when it is viewed as a set of instructions to attorneys involved in litigation concerning procedural issues. Attorneys now know how to make a persuasive showing on a procedural “due process” claim, and the probable effect of the approach is to discourage litigation drawing its motive force from the narrow (even if compelling) circumstances of a particular individual’s position. The hard problem for the courts in the Mathews approach, which may be unavoidable, is suggested by the absence of fixed doctrine about the content of “due process” and by the very breadth of the inquiry required to establish its demands in a particular context. A judge has few reference points to begin with, and must decide on the basis of considerations (such as the nature of a government program or the probable impact of a procedural requirement) that are very hard to develop in a trial.

While there is no definitive list of the “required procedures” that due process requires, Judge Henry Friendly generated a list that remains highly influential, as to both content and relative priority:

- An unbiased tribunal.

- Notice of the proposed action and the grounds asserted for it.

- Opportunity to present reasons why the proposed action should not be taken.

- The right to present evidence, including the right to call witnesses.

- The right to know opposing evidence.

- The right to cross-examine adverse witnesses.

- A decision based exclusively on the evidence presented.

- Opportunity to be represented by counsel.

- Requirement that the tribunal prepare a record of the evidence presented.

- Requirement that the tribunal prepare written findings of fact and reasons for its decision.

This is not a list of procedures which are required to prove due process, but rather a list of the kinds of procedures that might be claimed in a “due process” argument, roughly in order of their perceived importance.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/due_process

Substantive Due Process

Substantive due process is the principle that the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments protect fundamental rights from government interference. Specifically, the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments prohibit the government from depriving any person of “life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” The Fifth Amendment applies to federal action, and the Fourteenth applies to state action. Compare with procedural due process.

The Supreme Court’s first foray into defining which government actions violate substantive due process was during the Lochner Era. The Court determined that the freedom to contract and other economic rights were fundamental, and state efforts to control employee-employer relations, such as minimum wages, were struck down. In 1937, the Supreme Court rejected the Lochner Era’s interpretation of substantive due process in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379 (1937) by allowing Washington to implement a minimum wage for women and minors. One year later, in footnote 4 of U.S. v. Carolene Products, 304 U.S. 144 (1938), the Supreme Court indicated that substantive due process would apply to: “rights enumerated in and derived from the first Eight Amendments to the Constitution, the right to participate in the political process, such as the rights of voting, association, and free speech, and the rights of ‘discrete and insular minorities.’”

Following Carolene Products, the U.S. Supreme Court has determined that fundamental rights protected by substantive due process are those deeply rooted in U.S. history and tradition, viewed in light of evolving social norms. These rights are not explicitly listed in the Bill of Rights, but rather are the penumbra of certain amendments that refer to or assume the existence of such rights. This has led the Supreme Court to find that personal and relational rights, as opposed to economic rights, are fundamental and protected. Specifically, the Supreme Court has interpreted substantive due process to include, among others, the following fundamental rights:

- The right to privacy, specifically a right to contraceptives. Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)

- The right to pre-viability abortion. Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, (1973)

- The right to marry a person of a different race. Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)

- The right to marry an individual of the same sex. Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015)

cited https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/substantive_due_process

The Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause

The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment is the source of an array of constitutional rights, including many of our most cherished—and most controversial. Consider the following rights that the Clause guarantees against the states:

- procedural protections, such as notice and a hearing before termination of entitlements such as publicly funded medical insurance;

- individual rights listed in the Bill of Rights, including freedom of speech, free exercise of religion, the right to bear arms, and a variety of criminal procedure protections;

- fundamental rights that are not specifically enumerated elsewhere in the Constitution, including the right to marry, the right to use contraception, and the right to abortion.

The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment echoes that of the Fifth Amendment. The Fifth Amendment, however, applies only against the federal government. After the Civil War, Congress adopted a number of measures to protect individual rights from interference by the states. Among them was the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibits the states from depriving “any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

When it was adopted, the Clause was understood to mean that the government could deprive a person of rights only according to law applied by a court. Yet since then, the Supreme Court has elaborated significantly on this core understanding. As the examples above suggest, the rights protected under the Fourteenth Amendment can be understood in three categories: (1) “procedural due process;” (2) the individual rights listed in the Bill of Rights, “incorporated” against the states; and (3) “substantive due process.”

Procedural Due Process

“Procedural due process” concerns the procedures that the government must follow before it deprives an individual of life, liberty, or property. The key questions are: What procedures satisfy due process? And what constitutes “life, liberty, or property”?

Historically, due process ordinarily entailed a jury trial. The jury determined the facts and the judge enforced the law. In past two centuries, however, states have developed a variety of institutions and procedures for adjudicating disputes. Making room for these innovations, the Court has determined that due process requires, at a minimum: (1) notice; (2) an opportunity to be heard; and (3) an impartial tribunal. Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank (1950).

With regard to the meaning of “life, liberty, and property,” perhaps the most notable development is the Court’s expansion of the notion of property beyond real or personal property. In the 1970 case of Goldberg v. Kelly, the Court found that some governmental benefits—in that case, welfare benefits—amount to “property” with due process protections. Courts evaluate the procedure for depriving someone of a “new property” right by considering: (1) the nature of the property right; (2) the adequacy of the procedure compared to other procedures; and (3) the burdens that other procedures would impose on the state. Mathews v. Eldridge (1976).

“Incorporation” of the Bill of Rights Against the States

The Bill of Rights—comprised of the first ten amendments to the Constitution—originally applied only to the federal government. Barron v. Baltimore (1833). Those who sought to protect their rights from state governments had to rely on state constitutions and laws.

One of the purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment was to provide federal protection of individual rights against the states. Early on, however, the Supreme Court foreclosed the Fourteenth Amendment Privileges or Immunities Clause as a source of robust individual rights against the states. The Slaughter-House Cases (1873). Since then, the Court has held that the Due Process Clause “incorporates” many—but not all—of the individual protections of the Bill of Rights against the states. If a provision of the Bill of Rights is “incorporated” against the states, this means that the state governments, as well as the federal government, are required to abide by it. If a right is not “incorporated” against the states, it applies only to the federal government.

A celebrated debate about incorporation occurred between two factions of the Supreme Court: one side believed that all of the rights should be incorporated wholesale, and the other believed that only certain rights could be asserted against the states. While the partial incorporation faction prevailed, its victory rang somewhat hollow). As a practical matter, almost all the rights in the Bill of Rights have been incorporated against the states. The exceptions are the Third Amendment’s restriction on quartering soldiers in private homes, the Fifth Amendment’s right to a grand jury trial, the Seventh Amendment’s right to jury trial in civil cases, and the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on excessive fines.

Substantive Due Process

The Court has also deemed the due process guarantees of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to protect certain substantive rights that are not listed (or “enumerated”) in the Constitution. The idea is that certain liberties are so important that they cannot be infringed without a compelling reason no matter how much process is given.

The Court’s decision to protect unenumerated rights through the Due Process Clause is a little puzzling. The idea of unenumerated rights is not strange—the Ninth Amendment itself suggests that the rights enumerated in the Constitution do not exhaust “others retained by the people.” The most natural textual source for those rights, however, is probably the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibits states from denying any citizen the “privileges and immunities” of citizenship. When The Slaughter-House Cases (1873) foreclosed that interpretation, the Court turned to the Due Process Clause as a source of unenumerated rights.

The “substantive due process” jurisprudence has been among the most controversial areas of Supreme Court adjudication. The concern is that five unelected Justices of the Supreme Court can impose their policy preferences on the nation, given that, by definition, unenumerated rights do not flow directly from the text of the Constitution.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the Court used the Due Process Clause to strike down economic regulations that sought to better the conditions of workers on the ground that they violated those workers’ “freedom of contract,” even though this freedom is not specifically guaranteed in the Constitution. The 1905 case of Lochner v. New York is a symbol of this “economic substantive due process,” and is now widely reviled as an instance of judicial activism. When the Court repudiated Lochner in 1937, the Justices signaled that they would tread carefully in the area of unenumerated rights. West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937).

Substantive due process, however, had a renaissance in the mid-twentieth century. In 1965, the Court struck down state bans on the use of contraception by married couples on the ground that it violated their “right to privacy.” Griswold v. Connecticut. Like the “freedom of contract,” the “right to privacy” is not explicitly guaranteed in the Constitution. However, the Court found that unlike the “freedom of contract,” the “right to privacy” may be inferred from the penumbras—or shadowy edges—of rights that are enumerated, such as the First Amendment’s right to assembly, the Third Amendment’s right to be free from quartering soldiers during peacetime, and the Fourth Amendment’s right to be free from unreasonable searches of the home. The “penumbra” theory allowed the Court to reinvigorate substantive due process jurisprudence.

In the wake of Griswold, the Court expanded substantive due process jurisprudence to protect a panoply of liberties, including the right of interracial couples to marry (1967), the right of unmarried individuals to use contraception (1972), the right to abortion (1973), the right to engage in intimate sexual conduct (2003), and the right of same-sex couples to marry (2015). The Court has also declined to extend substantive due process to some rights, such as the right to physician-assisted suicide (1997).

The proper methodology for determining which rights should be protected under substantive due process has been hotly contested. In 1961, Justice Harlan wrote an influential dissent in Poe v. Ullman, maintaining that the project of discerning such rights “has not been reduced to any formula,” but must be left to case-by-case adjudication. In 1997, the Court suggested an alternative methodology that was more restrictive: such rights would need to be “carefully descri[bed]” and, under that description, “deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions” and “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.” Washington v. Glucksberg (1997). However, in recognizing a right to same-sex marriage in 2015, the Court not only limited that methodology, but also positively cited the Poe dissent. Obergefell v. Hodges. The Court’s approach in future cases remains unclear. source

Procedural Due Process Civil

SECTION 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

ANNOTATIONS

GenerallyDue process requires that the procedures by which laws are applied must be evenhanded, so that individuals are not subjected to the arbitrary exercise of government power.737 Exactly what procedures are needed to satisfy due process, however, will vary depending on the circumstances and subject matter involved.738 A basic threshold issue respecting whether due process is satisfied is whether the government conduct being examined is a part of a criminal or civil proceeding.739 The appropriate framework for assessing procedural rules in the field of criminal law is determining whether the procedure is offensive to the concept of fundamental fairness.740 In civil contexts, however, a balancing test is used that evaluates the government’s chosen procedure with respect to the private interest affected, the risk of erroneous deprivation of that interest under the chosen procedure, and the government interest at stake.741

Relevance of Historical Use.—The requirements of due process are determined in part by an examination of the settled usages and modes of proceedings of the common and statutory law of England during pre-colonial times and in the early years of this country.742 In other words, the antiquity of a legal procedure is a factor weighing in its favor. However, it does not follow that a procedure settled in English law and adopted in this country is, or remains, an essential element of due process of law. If that were so, the procedure of the first half of the seventeenth century would be “fastened upon American jurisprudence like a strait jacket, only to be unloosed by constitutional amendment.”743 Fortunately, the states are not tied down by any provision of the Constitution to the practice and procedure that existed at the common law, but may avail themselves of the wisdom gathered by the experience of the country to make changes deemed to be necessary.744

Non-Judicial Proceedings.—A court proceeding is not a requisite of due process.745 Administrative and executive proceedings are not judicial, yet they may satisfy the Due Process Clause.746 Moreover, the Due Process Clause does not require de novo judicial review of the factual conclusions of state regulatory agencies,747 and may not require judicial review at all.748 Nor does the Fourteenth Amendment prohibit a state from conferring judicial functions upon non-judicial bodies, or from delegating powers to a court that are legislative in nature.749 Further, it is up to a state to determine to what extent its legislative, executive, and judicial powers should be kept distinct and separate.750

The Requirements of Due Process.—Although due process tolerates variances in procedure “appropriate to the nature of the case,”751 it is nonetheless possible to identify its core goals and requirements. First, “[p]rocedural due process rules are meant to protect persons not from the deprivation, but from the mistaken or unjustified deprivation of life, liberty, or property.”752 Thus, the required elements of due process are those that “minimize substantively unfair or mistaken deprivations” by enabling persons to contest the basis upon which a state proposes to deprive them of protected interests.753 The core of these requirements is notice and a hearing before an impartial tribunal. Due process may also require an opportunity for confrontation and cross-examination, and for discovery; that a decision be made based on the record, and that a party be allowed to be represented by counsel.

(1) Notice. “An elementary and fundamental requirement of due process in any proceeding which is to be accorded finality is notice reasonably calculated, under all the circumstances, to apprise interested parties of the pendency of the action and afford them an opportunity to present their objections.”754 This may include an obligation, upon learning that an attempt at notice has failed, to take “reasonable followup measures” that may be available.755 In addition, notice must be sufficient to enable the recipient to determine what is being proposed and what he must do to prevent the deprivation of his interest.756 Ordinarily, service of the notice must be reasonably structured to assure that the person to whom it is directed receives it.757 Such notice, however, need not describe the legal procedures necessary to protect one’s interest if such procedures are otherwise set out in published, generally available public sources.758

(2) Hearing. “[S]ome form of hearing is required before an individual is finally deprived of a property [or liberty] interest.”759 This right is a “basic aspect of the duty of government to follow a fair process of decision making when it acts to deprive a person of his possessions. The purpose of this requirement is not only to ensure abstract fair play to the individual. Its purpose, more particularly, is to protect his use and possession of property from arbitrary encroachment . . . .”760 Thus, the notice of hearing and the opportunity to be heard “must be granted at a meaningful time and in a meaningful manner.”761

(3) Impartial Tribunal. Just as in criminal and quasi-criminal cases,762 an impartial decisionmaker is an essential right in civil proceedings as well.763 “The neutrality requirement helps to guarantee that life, liberty, or property will not be taken on the basis of an erroneous or distorted conception of the facts or the law. . . . At the same time, it preserves both the appearance and reality of fairness . . . by ensuring that no person will be deprived of his interests in the absence of a proceeding in which he may present his case with assurance that the arbiter is not predisposed to find against him.”764 Thus, a showing of bias or of strong implications of bias was deemed made where a state optometry board, made up of only private practitioners, was proceeding against other licensed optometrists for unprofessional conduct because they were employed by corporations. Since success in the board’s effort would redound to the personal benefit of private practitioners, the Court thought the interest of the board members to be sufficient to disqualify them.765

There is, however, a “presumption of honesty and integrity in those serving as adjudicators,”766 so that the burden is on the objecting party to show a conflict of interest or some other specific reason for disqualification of a specific officer or for disapproval of the system. Thus, combining functions within an agency, such as by allowing members of a State Medical Examining Board to both investigate and adjudicate a physician’s suspension, may raise substantial concerns, but does not by itself establish a violation of due process.767 The Court has also held that the official or personal stake that school board members had in a decision to fire teachers who had engaged in a strike against the school system in violation of state law was not such so as to disqualify them.768 Sometimes, to ensure an impartial tribunal, the Due Process Clause requires a judge to recuse himself from a case. In Caperton v. A. T. Massey Coal Co. , Inc., the Court noted that “most matters relating to judicial disqualification [do] not rise to a constitutional level,” and that “matters of kinship, personal bias, state policy, [and] remoteness of interest, would seem generally to be matters merely of legislative discretion.”769 The Court added, however, that “[t]he early and leading case on the subject” had “concluded that the Due Process Clause incorporated the common-law rule that a judge must recuse himself when he has ‘a direct, personal, substantial, pecuniary interest’ in a case.”770 In addition, although “[p]ersonal bias or prejudice ‘alone would not be sufficient basis for imposing a constitutional requirement under the Due Process Clause,’” there “are circumstances ‘in which experience teaches that the probability of actual bias on the part of the judge or decisionmaker is too high to be constitutionally tolerable.’”771 These circumstances include “where a judge had a financial interest in the outcome of a case” or “a conflict arising from his participation in an earlier proceeding.”772 In such cases, “[t]he inquiry is an objective one. The Court asks not whether the judge is actually, subjectively biased, but whether the average judge in his position is ‘likely’ to be neutral, or whether there is an unconstitutional ‘potential for bias.’”773 In Caperton, a company appealed a jury verdict of $50 million, and its chairman spent $3 million to elect a justice to the Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia at a time when “[i]t was reasonably foreseeable . . . that the pending case would be before the newly elected justice.”774 This $3 million was more than the total amount spent by all other supporters of the justice and three times the amount spent by the justice’s own committee. The justice was elected, declined to recuse himself, and joined a 3-to-2 decision overturning the jury verdict. The Supreme Court, in a 5-to-4 opinion written by Justice Kennedy, “conclude[d] that there is a serious risk of actual bias—based on objective and reasonable perceptions—when a person with a personal stake in a particular case had a significant and disproportionate influence in placing the judge on the case by raising funds or directing the judge’s election campaign when the case was pending or imminent.”775

Subsequently, in Williams v. Pennsylvania, the Court found that the right of due process was violated when a judge on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court—who participated in case denying post-conviction relief to a prisoner convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death—had, in his former role as a district attorney, given approval to seek the death penalty in the prisoner’s case.776 Relying on Caperton, which the Court viewed as having set forth an “objective standard” that requires recusal when the likelihood of bias on the part of the judge is “too high to be constitutionally tolerable,”777 the Williams Court specifically held that there is an impermissible risk of actual bias when a judge had previously had a “significant, personal involvement as a prosecutor in a critical decision regarding the defendant’s case.”778 The Court based its holding, in part, on earlier cases which had found impermissible bias occurs when the same person serves as both “accuser” and “adjudicator” in a case, which the Court viewed as having happened in Williams.779 It also reasoned that authorizing another person to seek the death penalty represents “significant personal involvement” in a case,780 and took the view that the involvement of multiple actors in a case over many years “only heightens”—rather than mitigates—the “need for objective rules preventing the operation of bias that otherwise might be obscured.”781 As a remedy, the case was remanded for reevaluation by the reconstituted Pennsylvania Supreme Court, notwithstanding the fact that the judge in question did not cast the deciding vote, as the Williams Court viewed the judge’s participation in the multi-member panel’s deliberations as sufficient to taint the public legitimacy of the underlying proceedings and constitute reversible error.782

(4) Confrontation and Cross-Examination. “In almost every setting where important decisions turn on questions of fact, due process requires an opportunity to confront and cross-examine adverse witnesses.”783 Where the “evidence consists of the testimony of individuals whose memory might be faulty or who, in fact, might be perjurers or persons motivated by malice, vindictiveness, intolerance, prejudice, or jealously,” the individual’s right to show that it is untrue depends on the rights of confrontation and cross-examination. “This Court has been zealous to protect these rights from erosion. It has spoken out not only in criminal cases, . . . but also in all types of cases where administrative . . . actions were under scrutiny.”784

(5) Discovery. The Court has never directly confronted this issue, but in one case it did observe in dictum that “where governmental action seriously injures an individual, and the reasonableness of the action depends on fact findings, the evidence used to prove the Government’s case must be disclosed to the individual so that he has an opportunity to show that it is untrue.”785 Some federal agencies have adopted discovery rules modeled on the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and the Administrative Conference has recommended that all do so.786 There appear to be no cases, however, holding they must, and there is some authority that they cannot absent congressional authorization.787

(6) Decision on the Record. Although this issue arises principally in the administrative law area,788 it applies generally. “[T]he decisionmaker’s conclusion . . . must rest solely on the legal rules and evidence adduced at the hearing. To demonstrate compliance with this elementary requirement, the decisionmaker should state the reasons for his determination and indicate the evidence he relied on, though his statement need not amount to a full opinion or even formal findings of fact and conclusions of law.”789

(7) Counsel. In Goldberg v. Kelly, the Court held that a government agency must permit a welfare recipient who has been denied benefits to be represented by and assisted by counsel.790 In the years since, the Court has struggled with whether civil litigants in court and persons before agencies who could not afford retained counsel should have counsel appointed and paid for, and the matter seems far from settled. The Court has established a presumption that an indigent does not have the right to appointed counsel unless his “physical liberty” is threatened.791 Moreover, that an indigent may have a right to appointed counsel in some civil proceedings where incarceration is threatened does not mean that counsel must be made available in all such cases. Rather, the Court focuses on the circumstances in individual cases, and may hold that provision of counsel is not required if the state provides appropriate alternative safeguards.792

Though the calculus may vary, cases not involving detention also are determined on a casebycase basis using a balancing standard.793

For instance, in a case involving a state proceeding to terminate the parental rights of an indigent without providing her counsel, the Court recognized the parent’s interest as “an extremely important one.” The Court, however, also noted the state’s strong interest in protecting the welfare of children. Thus, as the interest in correct fact-finding was strong on both sides, the proceeding was relatively simple, no features were present raising a risk of criminal liability, no expert witnesses were present, and no “specially troublesome” substantive or procedural issues had been raised, the litigant did not have a right to appointed counsel.794 In other due process cases involving parental rights, the Court has held that due process requires special state attention to parental rights.795 Thus, it would appear likely that in other parental right cases, a right to appointed counsel could be established.

The Procedure That Is Due ProcessThe Interests Protected: “Life, Liberty and Property”.— The language of the Fourteenth Amendment requires the provision of due process when an interest in one’s “life, liberty or property” is threatened.796 Traditionally, the Court made this determination by reference to the common understanding of these terms, as embodied in the development of the common law.797 In the 1960s, however, the Court began a rapid expansion of the “liberty” and “property” aspects of the clause to include such non-traditional concepts as conditional property rights and statutory entitlements. Since then, the Court has followed an inconsistent path of expanding and contracting the breadth of these protected interests. The “life” interest, on the other hand, although often important in criminal cases, has found little application in the civil context.

The Property Interest.—The expansion of the concept of “property rights” beyond its common law roots reflected a recognition by the Court that certain interests that fall short of traditional property rights are nonetheless important parts of people’s economic well-being. For instance, where household goods were sold under an installment contract and title was retained by the seller, the possessory interest of the buyer was deemed sufficiently important to require procedural due process before repossession could occur.798 In addition, the loss of the use of garnished wages between the time of garnishment and final resolution of the underlying suit was deemed a sufficient property interest to require some form of determination that the garnisher was likely to prevail.799 Furthermore, the continued possession of a driver’s license, which may be essential to one’s livelihood, is protected; thus, a license should not be suspended after an accident for failure to post a security for the amount of damages claimed by an injured party without affording the driver an opportunity to raise the issue of liability.800

A more fundamental shift in the concept of property occurred with recognition of society’s growing economic reliance on government benefits, employment, and contracts,801 and with the decline of the “right-privilege” principle. This principle, discussed previously in the First Amendment context,802 was pithily summarized by Justice Holmes in dismissing a suit by a policeman protesting being fired from his job: “The petitioner may have a constitutional right to talk politics, but he has no constitutional right to be a policeman.”803 Under this theory, a finding that a litigant had no “vested property interest” in government employment,804 or that some form of public assistance was “only” a privilege,805 meant that no procedural due process was required before depriving a person of that interest.806 The reasoning was that, if a government was under no obligation to provide something, it could choose to provide it subject to whatever conditions or procedures it found appropriate.

The conceptual underpinnings of this position, however, were always in conflict with a line of cases holding that the government could not require the diminution of constitutional rights as a condition for receiving benefits. This line of thought, referred to as the “unconstitutional conditions” doctrine, held that, “even though a person has no ‘right’ to a valuable government benefit and even though the government may deny him the benefit for any number of reasons, it may not do so on a basis that infringes his constitutionally protected interests—especially, his interest in freedom of speech.”807 Nonetheless, the two doctrines coexisted in an unstable relationship until the 1960s, when the right-privilege distinction started to be largely disregarded.808

Concurrently with the virtual demise of the “right-privilege” distinction, there arose the “entitlement” doctrine, under which the Court erected a barrier of procedural—but not substantive—protections809 against erroneous governmental deprivation of something it had within its discretion bestowed. Previously, the Court had limited due process protections to constitutional rights, traditional rights, common law rights and “natural rights.” Now, under a new “positivist” approach, a protected property or liberty interest might be found based on any positive governmental statute or governmental practice that gave rise to a legitimate expectation. Indeed, for a time it appeared that this positivist conception of protected rights was going to displace the traditional sources.

As noted previously, the advent of this new doctrine can be seen in Goldberg v. Kelly,810 in which the Court held that, because termination of welfare assistance may deprive an eligible recipient of the means of livelihood, the government must provide a pretermination evidentiary hearing at which an initial determination of the validity of the dispensing agency’s grounds for termination may be made. In order to reach this conclusion, the Court found that such benefits “are a matter of statutory entitlement for persons qualified to receive them.”811 Thus, where the loss or reduction of a benefit or privilege was conditioned upon specified grounds, it was found that the recipient had a property interest entitling him to proper procedure before termination or revocation.

At first, the Court’s emphasis on the importance of the statutory rights to the claimant led some lower courts to apply the Due Process Clause by assessing the weights of the interests involved and the harm done to one who lost what he was claiming. This approach, the Court held, was inappropriate. “[W]e must look not to the ‘weight’ but to the nature of the interest at stake. . . . We must look to see if the interest is within the Fourteenth Amendment’s protection of liberty and property.”812 To have a property interest in the constitutional sense, the Court held, it was not enough that one has an abstract need or desire for a benefit or a unilateral expectation. He must rather “have a legitimate claim of entitlement” to the benefit. “Property interests, of course, are not created by the Constitution. Rather, they are created and their dimensions are defined by existing rules or understandings that stem from an independent source such as state law—rules or understandings that secure certain benefits and that support claims of entitlement to those benefits.”813

Consequently, in Board of Regents v. Roth, the Court held that the refusal to renew a teacher’s contract upon expiration of his one-year term implicated no due process values because there was nothing in the public university’s contract, regulations, or policies that “created any legitimate claim” to reemployment.814 By contrast, in Perry v. Sindermann,815 a professor employed for several years at a public college was found to have a protected interest, even though his employment contract had no tenure provision and there was no statutory assurance of it.816 The “existing rules or understandings” were deemed to have the characteristics of tenure, and thus provided a legitimate expectation independent of any contract provision.817

The Court has also found “legitimate entitlements” in a variety of other situations besides employment. In Goss v. Lopez,818 an Ohio statute provided for both free education to all residents between five and 21 years of age and compulsory school attendance; thus, the state was deemed to have obligated itself to accord students some due process hearing rights prior to suspending them, even for such a short period as ten days. “Having chosen to extend the right to an education to people of appellees’ class generally, Ohio may not withdraw that right on grounds of misconduct, absent fundamentally fair procedures to determine whether the misconduct has occurred.”819 The Court is highly deferential, however, to school dismissal decisions based on academic grounds.820

The further one gets from traditional precepts of property, the more difficult it is to establish a due process claim based on entitlements. In Town of Castle Rock v. Gonzales,821 the Court considered whether police officers violated a constitutionally protected property interest by failing to enforce a restraining order obtained by an estranged wife against her husband, despite having probable cause to believe the order had been violated. While noting statutory language that required that officers either use “every reasonable means to enforce [the] restraining order” or “seek a warrant for the arrest of the restrained person,” the Court resisted equating this language with the creation of an enforceable right, noting a longstanding tradition of police discretion coexisting with apparently mandatory arrest statutes.822 Finally, the Court even questioned whether finding that the statute contained mandatory language would have created a property right, as the wife, with no criminal enforcement authority herself, was merely an indirect recipient of the benefits of the governmental enforcement scheme.823

In Arnett v. Kennedy,824 an incipient counter-revolution to the expansion of due process was rebuffed, at least with respect to entitlements. Three Justices sought to qualify the principle laid down in the entitlement cases and to restore in effect much of the right-privilege distinction, albeit in a new formulation. The case involved a federal law that provided that employees could not be discharged except for cause, and the Justices acknowledged that due process rights could be created through statutory grants of entitlements. The Justices, however, observed that the same law specifically withheld the procedural protections now being sought by the employees. Because “the property interest which appellee had in his employment was itself conditioned by the procedural limitations which had accompanied the grant of that interest,”825 the employee would have to “take the bitter with the sweet.”826 Thus, Congress (and by analogy state legislatures) could qualify the conferral of an interest by limiting the process that might otherwise be required.

But the other six Justices, although disagreeing among themselves in other respects, rejected this attempt to formulate the issue. “This view misconceives the origin of the right to procedural due process,” Justice Powell wrote. “That right is conferred not by legislative grace, but by constitutional guarantee. While the legislature may elect not to confer a property interest in federal employment, it may not constitutionally authorize the deprivation of such an interest, once conferred, without appropriate procedural safeguards.”827 Yet, in Bishop v. Wood,828 the Court accepted a district court’s finding that a policeman held his position “at will” despite language setting forth conditions for discharge. Although the majority opinion was couched in terms of statutory construction, the majority appeared to come close to adopting the three-Justice Arnett position, so much so that the dissenters accused the majority of having repudiated the majority position of the six Justices in Arnett. And, in Goss v. Lopez,829 Justice Powell, writing in dissent but using language quite similar to that of Justice Rehnquist in Arnett, seemed to indicate that the right to public education could be qualified by a statute authorizing a school principal to impose a ten-day suspension.830

Subsequently, however, the Court held squarely that, because “minimum [procedural] requirements [are] a matter of federal law, they are not diminished by the fact that the State may have specified its own procedures that it may deem adequate for determining the preconditions to adverse action.” Indeed, any other conclusion would allow the state to destroy virtually any state-created property interest at will.831 A striking application of this analysis is found in Logan v. Zimmerman Brush Co.,832 in which a state anti-discrimination law required the enforcing agency to convene a fact-finding conference within 120 days of the filing of the complaint. Inadvertently, the Commission scheduled the hearing after the expiration of the 120 days and the state courts held the requirement to be jurisdictional, necessitating dismissal of the complaint. The Court noted that various older cases had clearly established that causes of action were property, and, in any event, Logan’s claim was an entitlement grounded in state law and thus could only be removed “for cause.” This property interest existed independently of the 120-day time period and could not simply be taken away by agency action or inaction.833

The Liberty Interest.—With respect to liberty interests, the Court has followed a similarly meandering path. Although the traditional concept of liberty was freedom from physical restraint, the Court has expanded the concept to include various other protected interests, some statutorily created and some not.834 Thus, in Ingraham v. Wright,835 the Court unanimously agreed that school children had a liberty interest in freedom from wrongfully or excessively administered corporal punishment, whether or not such interest was protected by statute. “The liberty preserved from deprivation without due process included the right ‘generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized at common law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.’ . . . Among the historic liberties so protected was a right to be free from, and to obtain judicial relief for, unjustified intrusions on personal security.”836

The Court also appeared to have expanded the notion of “liberty” to include the right to be free of official stigmatization, and found that such threatened stigmatization could in and of itself require due process.837 Thus, in Wisconsin v. Constantineau,838 the Court invalidated a statutory scheme in which persons could be labeled “excessive drinkers,” without any opportunity for a hearing and rebuttal, and could then be barred from places where alcohol was served. The Court, without discussing the source of the entitlement, noted that the governmental action impugned the individual’s reputation, honor, and integrity.839

But, in Paul v. Davis,840 the Court appeared to retreat from recognizing damage to reputation alone, holding instead that the liberty interest extended only to those situations where loss of one’s reputation also resulted in loss of a statutory entitlement. In Davis, the police had included plaintiff’s photograph and name on a list of “active shoplifters” circulated to merchants without an opportunity for notice or hearing. But the Court held that “Kentucky law does not extend to respondent any legal guarantee of present enjoyment of reputation which has been altered as a result of petitioners’ actions. Rather, his interest in reputation is simply one of a number which the State may protect against injury by virtue of its tort law, providing a forum for vindication of those interest by means of damage actions.”841 Thus, unless the government’s official defamation has a specific negative effect on an entitlement, such as the denial to “excessive drinkers” of the right to obtain alcohol that occurred in Constantineau, there is no protected liberty interest that would require due process.

A number of liberty interest cases that involve statutorily created entitlements involve prisoner rights, and are dealt with more extensively in the section on criminal due process. However, they are worth noting here. In Meachum v. Fano,842 the Court held that a state prisoner was not entitled to a fact-finding hearing when he was transferred to a different prison in which the conditions were substantially less favorable to him, because (1) the Due Process Clause liberty interest by itself was satisfied by the initial valid conviction, which had deprived him of liberty, and (2) no state law guaranteed him the right to remain in the prison to which he was initially assigned, subject to transfer for cause of some sort. As a prisoner could be transferred for any reason or for no reason under state law, the decision of prison officials was not dependent upon any state of facts, and no hearing was required.

In Vitek v. Jones,843 by contrast, a state statute permitted transfer of a prisoner to a state mental hospital for treatment, but the transfer could be effectuated only upon a finding, by a designated physician or psychologist, that the prisoner “suffers from a mental disease or defect” and “cannot be given treatment in that facility.” Because the transfer was conditioned upon a “cause,” the establishment of the facts necessary to show the cause had to be done through fair procedures. Interestingly, however, the Vitek Court also held that the prisoner had a “residuum of liberty” in being free from the different confinement and from the stigma of involuntary commitment for mental disease that the Due Process Clause protected. Thus, the Court has recognized, in this case and in the cases involving revocation of parole or probation,844 a liberty interest that is separate from a statutory entitlement and that can be taken away only through proper procedures.

But, with respect to the possibility of parole or commutation or otherwise more rapid release, no matter how much the expectancy matters to a prisoner, in the absence of some form of positive entitlement, the prisoner may be turned down without observance of procedures.845 Summarizing its prior holdings, the Court recently concluded that two requirements must be present before a liberty interest is created in the prison context: the statute or regulation must contain “substantive predicates” limiting the exercise of discretion, and there must be explicit “mandatory language” requiring a particular outcome if substantive predicates are found.846 In an even more recent case, the Court limited the application of this test to those circumstances where the restraint on freedom imposed by the state creates an “atypical and significant hardship.”847

Proceedings in Which Procedural Due Process Need Not Be Observed.—Although due notice and a reasonable opportunity to be heard are two fundamental protections found in almost all systems of law established by civilized countries,848 there are certain proceedings in which the enjoyment of these two conditions has not been deemed to be constitutionally necessary. For instance, persons adversely affected by a law cannot challenge its validity on the ground that the legislative body that enacted it gave no notice of proposed legislation, held no hearings at which the person could have presented his arguments, and gave no consideration to particular points of view. “Where a rule of conduct applies to more than a few people it is impracticable that everyone should have a direct voice in its adoption. The Constitution does not require all public acts to be done in town meeting or an assembly of the whole. General statutes within the state power are passed that affect the person or property of individuals, sometimes to the point of ruin, without giving them a chance to be heard. Their rights are protected in the only way that they can be in a complex society, by their power, immediate or remote, over those who make the rule.”849

Similarly, when an administrative agency engages in a legislative function, as, for example, when it drafts regulations of general application affecting an unknown number of persons, it need not afford a hearing prior to promulgation.850 On the other hand, if a regulation, sometimes denominated an “order,” is of limited application, that is, it affects an identifiable class of persons, the question whether notice and hearing is required and, if so, whether it must precede such action, becomes a matter of greater urgency and must be determined by evaluating the various factors discussed below.851

One such factor is whether agency action is subject to later judicial scrutiny.852 In one of the initial decisions construing the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, the Court upheld the authority of the Secretary of the Treasury, acting pursuant to statute, to obtain money from a collector of customs alleged to be in arrears. The Treasury simply issued a distress warrant and seized the collector’s property, affording him no opportunity for a hearing, and requiring him to sue for recovery of his property. While acknowledging that history and settled practice required proceedings in which pleas, answers, and trials were requisite before property could be taken, the Court observed that the distress collection of debts due the crown had been the exception to the rule in England and was of long usage in the United States, and was thus sustainable.853

In more modern times, the Court upheld a procedure under which a state banking superintendent, after having taken over a closed bank and issuing notices to stockholders of their assessment, could issue execution for the amounts due, subject to the right of each stockholder to contest his liability for such an assessment by an affidavit of illegality. The fact that the execution was issued in the first instance by a governmental officer and not from a court, followed by personal notice and a right to take the case into court, was seen as unobjectionable.854

It is a violation of due process for a state to enforce a judgment against a party to a proceeding without having given him an opportunity to be heard sometime before final judgment is entered.855 With regard to the presentation of every available defense, however, the requirements of due process do not necessarily entail affording an opportunity to do so before entry of judgment. The person may be remitted to other actions initiated by him856 or an appeal may suffice. Accordingly, a surety company, objecting to the entry of a judgment against it on a supersedeas bond, without notice and an opportunity to be heard on the issue of liability, was not denied due process where the state practice provided the opportunity for such a hearing by an appeal from the judgment so entered. Nor could the company found its claim of denial of due process upon the fact that it lost this opportunity for a hearing by inadvertently pursuing the wrong procedure in the state courts.857 On the other hand, where a state appellate court reversed a trial court and entered a final judgment for the defendant, a plaintiff who had never had an opportunity to introduce evidence in rebuttal to certain testimony which the trial court deemed immaterial but which the appellate court considered material was held to have been deprived of his rights without due process of law.858

What Process Is Due.—The requirements of due process, as has been noted, depend upon the nature of the interest at stake, while the form of due process required is determined by the weight of that interest balanced against the opposing interests.859 The currently prevailing standard is that formulated in Mathews v. Eldridge,860 which concerned termination of Social Security benefits. “Identification of the specific dictates of due process generally requires consideration of three distinct factors: first, the private interest that will be affected by the official action; second, the risk of erroneous deprivation of such interest through the procedures used, and probable value, if any, of additional or substitute procedural safeguards; and, finally, the Government’s interest, including the function involved and the fiscal and administrative burdens that the additional or substitute procedural requirements would entail.”

The termination of welfare benefits in Goldberg v. Kelly,861 which could have resulted in a “devastating” loss of food and shelter, had required a predeprivation hearing. The termination of Social Security benefits at issue in Mathews would require less protection, however, because those benefits are not based on financial need and a terminated recipient would be able to apply for welfare if need be. Moreover, the determination of ineligibility for Social Security benefits more often turns upon routine and uncomplicated evaluations of data, reducing the likelihood of error, a likelihood found significant in Goldberg. Finally, the administrative burden and other societal costs involved in giving Social Security recipients a pretermination hearing would be high. Therefore, a post-termination hearing, with full retroactive restoration of benefits, if the claimant prevails, was found satisfactory.862

Application of the Mathews standard and other considerations brought some noteworthy changes to the process accorded debtors and installment buyers. Earlier cases, which had focused upon the interests of the holders of the property in not being unjustly deprived of the goods and funds in their possession, leaned toward requiring predeprivation hearings. Newer cases, however, look to the interests of creditors as well. “The reality is that both seller and buyer had current, real interests in the property, and the definition of property rights is a matter of state law. Resolution of the due process question must take account not only of the interests of the buyer of the property but those of the seller as well.”863

Thus, Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp.,864 which mandated predeprivation hearings before wages may be garnished, has apparently been limited to instances when wages, and perhaps certain other basic necessities, are in issue and the consequences of deprivation would be severe.865 Fuentes v. Shevin,866 which struck down a replevin statute that authorized the seizure of property (here household goods purchased on an installment contract) simply upon the filing of an ex parte application and the posting of bond, has been limited,867 so that an appropriately structured ex parte judicial determination before seizure is sufficient to satisfy due process.868 Thus, laws authorizing sequestration, garnishment, or other seizure of property of an alleged defaulting debtor need only require that (1) the creditor furnish adequate security to protect the debtor’s interest, (2) the creditor make a specific factual showing before a neutral officer or magistrate, not a clerk or other such functionary, of probable cause to believe that he is entitled to the relief requested, and (3) an opportunity be assured for an adversary hearing promptly after seizure to determine the merits of the controversy, with the burden of proof on the creditor.869

Similarly, applying the Mathews v. Eldridge standard in the context of government employment, the Court has held, albeit by a combination of divergent opinions, that the interest of the employee in retaining his job, the governmental interest in the expeditious removal of unsatisfactory employees, the avoidance of administrative burdens, and the risk of an erroneous termination combine to require the provision of some minimum pre-termination notice and opportunity to respond, followed by a full post-termination hearing, complete with all the procedures normally accorded and back pay if the employee is successful.870 Where the adverse action is less than termination of employment, the governmental interest is significant, and where reasonable grounds for such action have been established separately, then a prompt hearing held after the adverse action may be sufficient.871 In other cases, hearings with even minimum procedures may be dispensed with when what is to be established is so pro forma or routine that the likelihood of error is very small.872 In a case dealing with negligent state failure to observe a procedural deadline, the Court held that the claimant was entitled to a hearing with the agency to pass upon the merits of his claim prior to dismissal of his action.873

In Brock v. Roadway Express, Inc.,874 a Court plurality applied a similar analysis to governmental regulation of private employment, determining that an employer may be ordered by an agency to reinstate a “whistle-blower” employee without an opportunity for a full evidentiary hearing, but that the employer is entitled to be informed of the substance of the employee’s charges, and to have an opportunity for informal rebuttal. The principal difference with the Mathews v. Eldridge test was that here the Court acknowledged two conflicting private interests to weigh in the equation: that of the employer “in controlling the makeup of its workforce” and that of the employee in not being discharged for whistleblowing. Whether the case signals a shift away from evidentiary hearing requirements in the context of regulatory adjudication will depend on future developments.875

A delay in retrieving money paid to the government is unlikely to rise to the level of a violation of due process. In City of Los Angeles v. David,876 a citizen paid a $134. 50 impoundment fee to retrieve an automobile that had been towed by the city. When he subsequently sought to challenge the imposition of this impoundment fee, he was unable to obtain a hearing until 27 days after his car had been towed. The Court held that the delay was reasonable, as the private interest affected—the temporary loss of the use of the money—could be compensated by the addition of an interest payment to any refund of the fee. Further factors considered were that a 30-day delay was unlikely to create a risk of significant factual errors, and that shortening the delay significantly would be administratively burdensome for the city.

In another context, the Supreme Court applied the Mathews test to strike down a provision in Colorado’s Exoneration Act.877 That statute required individuals whose criminal convictions had been invalidated to prove their innocence by clear and convincing evidence in order to recoup any fines, penalties, court costs, or restitution paid to the state as a result of the conviction.878 The Court, noting that “[a]bsent conviction of crime, one is presumed innocent,”879 concluded that all three considerations under Mathews “weigh[ed] decisively against Colorado’s scheme.”880 Specifically, the Court reasoned that (1) those affected by the Colorado statute have an “obvious interest” in regaining their funds;881 (2) the burden of proving one’s innocence by “clear and convincing” evidence unacceptably risked erroneous deprivation of those funds;882 and (3) the state had “no countervailing interests” in withholding money to which it had “zero claim of right.”883 As a result, the Court held that the state could not impose “anything more than minimal procedures” for the return of funds that occurred as a result of a conviction that was subsequently invalidated.884