Monitored Visits and the Removal of Parental Constitutional Rights

Bridget Neal • Jun 15, 2022

Introduction

Only in family court can subjective opinions and a game of “he said she said” lead to the removal of one’s parental rights. To add injury to insult courts will often use monitored visits which is often more harmful than no visitation rights at all. Monitored visits give children the perception, regardless of the truth, that their parent is some sort of danger to them. In addition, they operate as a de facto gag order because by “monitoring” the visitation they are also monitoring what the parent says. Regardless of the truth a parent tells their child, that information can be held against them, thus operating to stifle a parent’s free speech when communicating with their child during these visits. Meanwhile, the parent without supervised visits is free say anything they want to their child. This enables this parent to create an even greater negative and false perception of the aggrieved parent.

The removing of a parent’s fundamental right to parent in addition to the restriction of their First Amendment rights is often done in the name of the “best interests of the child.” But by what authority does this arbitrary standard supersede one’s Constitutional rights? Even if there were authority, which there is not, study after study has shown that it is rarely in the best interest of the child to keep them away from one of their parents. Yet, these decisions are made daily in courts throughout this country.

These are significant problems in desperate need for some viable solutions. We need alternatives to the “best interest of the child” standard. This is made especially obvious when it leads to stripping parents of their fundamental rights are subjecting them to harmful restrictions such as monitored visits. In addition to a new standard, we need a higher level of scrutiny. Beyond that, considering the number of parties effectively imprisoned in their state family court system, we need a federal solution that can be used to provide parties the relief necessary when there is no state solution. These changes are drastic, these changes are bold and, most importantly, these changes are necessary. This paper will explore both the problems and the potential solutions within the current family court system.

Problems

Monitored Visits, without cause, are a Violation of one’s Fundamental Right to Parent

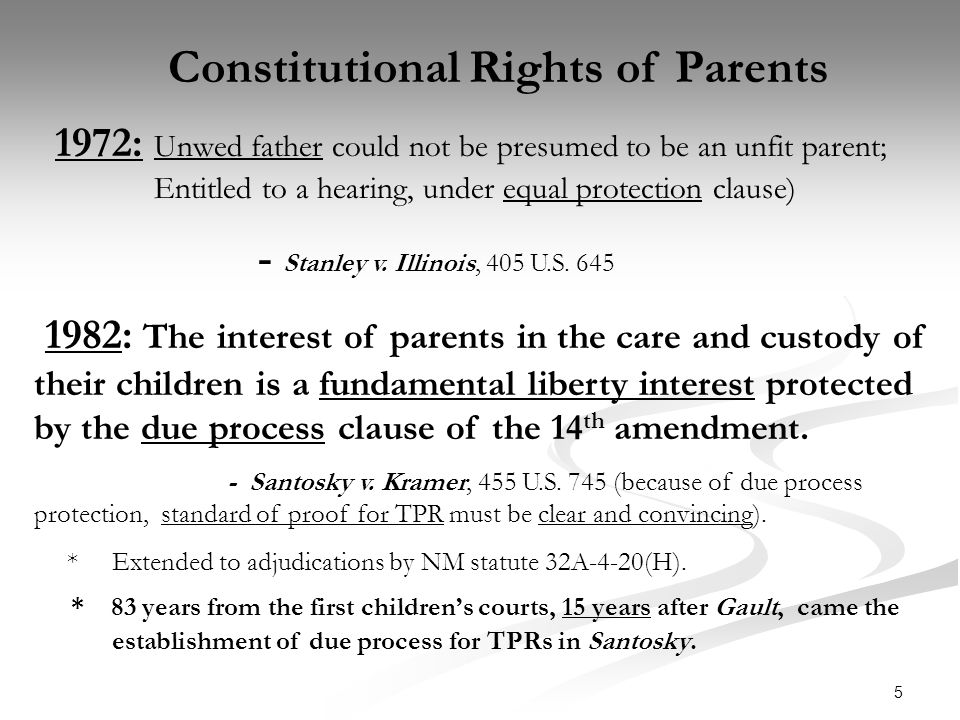

The 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states that, the State shall not “deprive any person of life liberty or property, without due process of law.” As it pertains to family law matters, the Supreme Court has held that this right includes “the right of the individual…to marry, establish a home and bring up children…and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized at common law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.” (1)

More explicitly, the Supreme Court has held that “the interest of parents in the care, custody, and control of their children— is perhaps the oldest of the fundamental liberty interests recognized by this [Supreme] Court…It is cardinal with us that the custody, care and nurture of the child reside first in the parents…” (2) When a court involves itself in this fundamental right it is, essentially, overriding the parents ability to determine what is in the best interests of the child. When a family court strips a parent of custodial rights and forces them to attend monitored visits, they have directly inserted themselves into a parent’s fundamental liberty interests. This is beyond micromanaging two parents’ joint custody schedule. By requiring monitored visits, the state is directly inserting itself into the family dynamic. Not only are they inserting themselves, but they are also reenforcing a perception on the aggrieved parent that has been repeated by the co-parent. As a result, monitored visits should only be issued in the direst of situations. Namely, situations in which there is a serious threat of physical or emotional harm. Otherwise, monitored visits without cause, are detrimental to the parent-child relationship and be considered nothing less than a violation of a parent’s fundamental Constitutional rights.

Monitored Visits are a de facto violation of a Parent’s First Amendment Rights

The First Amendment holds that “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech.” (3) This right extends to any state laws or the application thereof. So how do monitored visits infringe on one’s free speech rights? Well, let’s look at how we might have gotten to this point. One parent has had every aspect of their parental rights stripped away from them. The court, for whatever reason, has accepted one party’s subjective evidence over the others. This could be based on bias or numerous other factors. Regardless, the only opportunity the parent has to spend time with their children is in the presence of a court appointed monitor. The children have already been tainted by the other parent, as well as the court system. However, the aggrieved parent is prohibited from providing their side of the story to the children. The court system has already aligned with the other parent. You can be sure, that any attempt to exercise free speech during these monitored visits will not be free at all but will come with a cost. Certainly, it has the potential of having a further negative impact on their attempt to regain their Constitutional right to the custody of their children. As a result, during these monitored visits, an aggrieved parent is left with no choice but to keep quiet and let their children continue to believe whatever the other parent has been telling them during their unsupervised time with their children.

So, how do monitored visits come about? Most states have laws in place that designate specific reasons when the court has to take the drastic decision to monitor a parent’s visitation with their child. For instance, Louisiana places these restrictions on visitations when there is an issue of violence, domestic abuse, or sexual abuse. Thus, a court in Louisiana is justified in having monitored visits when there is evidence that one of these issues has arisen. The problem is family courts continually enforce monitored visits without any evidence of this type of abuse or violence occurring. Without any substantive evidence, such as a police filing or protective order, courts have made the drastic decision to impose supervised visitation on a parent. You might ask, by what grounds can a judge take such drastic action? But it happens all the time. And when this happens the aggrieved party is likely aware that those monitored visits may be nothing more than a pretense to catch them saying something they can use against them to further strip their custodial and parental rights. The result ends up being, the aggrieved parent is forced to keep quiet if they want to see their kids and, if not, even monitored visits will be taken away. While the parent knows that keeping quiet will just perpetuate the fraud of the other parent, they also know that speaking about it at a monitored visit will likely be held against them. As a result, monitored visits of these kind lead to a de facto violation of the parent’s first amendment rights.

A court order reducing, changing, or eliminating a parent’s custody or visitation rights because of a parent’s speech, is a violation of one’s First Amendment right. In a monitored visitation situation, a court may use the rationale that it is not in the best interest of the child to hear the aggrieved parent tell them their side of the story. The use of this subjective standard is than used as a means to stifle one’s First Amendment Rights. In family courts this can be done on a whim, without even a heightened showing of harm from the parent’s speech. This is yet another case in the family court system where state law and the subjective decision of judge’s trump a Constitutional right. Yet, another reason for massive reform in the family court system.

Monitored Visits (and other parental limitations) are almost never in the Best Interest of the Child

The argument that family court’s make is that their decision in the best interests of the child. Putting aside the fact that Judges are not omniscient, it has been shown that this is usually not the case when the result is the child being alienated from one parent. It has been clearly shown that when children are deprived of time with one of their parents, it leads to a detrimental effect to many aspects of their life. This can lead to emotional, physical, and behavioral problems and can be seen in various measures of their life including academic endeavors, depression, drug abuse and other health issues. Children that have both of their natural parents in their lives have better overall outcomes in life. These reasons show that when the “best interests of the child” standard is used to curtail a parent’s right it is usually NOT in the best interests of the child. Courts are getting it wrong. Without clear and convincing evidence of harm to the child, courts micromanaging of parental rights is causing more harm than good. Its defeating the very purpose this inadequate and subjective standard was designed for.

Trial courts are ignoring or failing to take into consideration the actual harm these decisions are having on the children. By hiding behind this standard, courts are making decisions that are exacerbating the family relationship. What’s worse, courts are protected from any meaningful review or accountability by simply stating the magic words, that the decision is in “the best interests of the child.” But courts are not perfect nor are they always right. They wield a great power, and the true consequences are borne by the aggrieved parent and the children that have now had a relationship with one of their parents severed, maybe permanently.

The “Best Interests of the Child” Standard is not Greater than Constitutional Rights as a Parent

Speaking of the Best Interests of the Child Standard, since when does this standard exceed rights explicitly set forth by the United States Constitution? When looking at the role the law has played in a parents’ fundamental right to direct the care, custody, and control of their children, it appears that the State’s power in domestic matters has obfuscated the protections and rights set forth in the Constitution. When a court takes away a parent’s right to take care of their children the court is placing their subjective analysis of a child’s best interest above the objective constitutional right of the parent. However, the correct application is to subordinate these subjective standards, state statutes, rules and regulations below the fundamental rights that were recognized by the United States Constitution and confirmed time and time again by the U.S. Supreme Court. The U.S. Constitution even explicitly says so – “The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people” (4) and “… No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States ….” (5)

The adversarial process, which includes the family court, is a win or lose competition. Parents, and their attorneys, have the sole goal of proving that they should be the winner. In this zero-sum game there is more than one loser. Oftentimes, the greatest loser in this process is the child, who’s “best interest” is just the pretext for announcing a winner and loser.

Solutions

A Better Standard Moving Forward

Parents have a fundamental right to direct the care of their children. This right should not be interfered with unless a parent is objectively proven to be unfit. In fact, courts have held that the Constitution “protects a private realm of family life which the state cannot enter without compelling justification.” (6) The problem is, courts across the country have failed to provide an adequate test to protect a parent’s Constitutional rights. The United States Supreme Court has held, “the child is not the mere creature of the State; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.” (7) This was further bolstered by a more recent case that held, “so long as a parent adequately cares for his or her children (i.e., is fit), there will normally be no reason for the State to inject itself into the private realm of the family to further question the ability of the parent to make the best decisions concerning the rearing of that parent’s child.” (8)

There must be a better standard moving forward. While the “best interests of the child” standard seems noble, it has provided cover for too long to allow judges to overreach into the sacred parent-child dynamic. More to the point, it is not a Constitutional right and due to its vagueness, it’s not even a measurable standard. A failure to have a standard that places a greater priority on the parent and their rights is unconstitutional. There is case after case in the Supreme Court where the rights of parents are considered of the utmost importance. Yet our state courts have no connection between the standards they follow and these Constitutional rights. Instead, they have an unchallenged ability to limit or terminate a parent’s rights using an undefinable and subjective standard.

In Court there are rules of evidence that must be followed. In addition, substantive due process must be afforded when a fundamental right is involved. Consistently, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that the interest of parents “in the care, custody and control of their children-is perhaps the oldest of the fundamental liberty interests recognized by this court.” (9) The Supreme Court has held that, “in light of this extensive precedent, it cannot now be doubted that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protects the fundamental rights of parents to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of their children.” (10) Yet, the best interests of the child standard, and the judge’s ability to make a wide range of impactful decisions under this subjective standard, completely fails to address these Constitutional rights. First, the standard itself is hard to define. Typically, the “best interests of the child” standard has several factors, giving the family court system an incredible amount of flexibility in how they evaluate those factors. Under this standard custody evaluations and biased testimony are sufficient grounds upon which parental rights can be removed. The family court systems overreliance on this subjective standard in a custody dispute ignores the high burden the U.S. Supreme Court has placed on courts when altering parental rights. By seeking cover under this standard, while refusing to consider parental rights, the courts are denying parents of a truly meaningful hearing and, thus, denying them their due process. The Family Court System should view parents as fit until objectively proven otherwise. The default, not the exception, should be the protection of both parent’s constitutional rights. Simply relying on the subjective “best interests of the child” standard completely fails to meet the required legal standard afforded by the U.S. Constitution.

It is not being argued that a parent’s rights should exceed the rights of their children. What is being argued is that the “best interests of the child” standard is impossible to fairly apply, fraught with ambiguities, and is often used to violate a parent’s clear and objective Constitutional rights. When dealing with two parents with equal parental and Constitutional rights, an objective test focusing on the fitness of the parent is what’s needed. Not a system where custody evaluators can offer highly subjective opinions, fraught with personal hostilities and biases, and the judge can then strip away one’s parental rights under the guise that it is in the best interests of the child.

A Higher Level of Scrutiny

Due to the Constitutional rights involved, all custody cases should be subject to the highest level of scrutiny, strict scrutiny. If we can strip away one’s constitutional parental rights without strict scrutiny than what, if anything, would require strict scrutiny? Strict scrutiny would then apply to any situation in which the court is altering a parent’s rights. For instance, when a court requires monitored visits, not only are they drastically altering the parent-child dynamic, but they are also influencing the child’s perception of the aggrieved parent.

Consistently, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that the interest of parents “in the care, custody and control of their children-is perhaps the oldest of the fundamental liberty interests recognized by this court.” (11) The Supreme Court has held that, strict scrutiny (or at least an indistinguishable form of heightened scrutiny) should be applied in cases involving a parents fundamental right of custody of their child. (12) Yet, family courts are making life-altering decisions without having to meet these legal standards. Whether it be the custody evaluation, or the hearing itself, family courts are given incredible decision-making authority over one’s family while not being required to adhere to the stringent evidentiary rules or burdens imposed by strict scrutiny. A family court judge’s ability to make these decisions with little to no scrutiny ignores the high burden the U.S. Supreme Court has placed on courts when altering parental rights.

In not applying strict scrutiny, family law courts are conflicting with the Supreme Court and, in some cases, their own legislature. A jurisprudence has developed when, absent some clear abuse of discretion, a family court can strip away a parent’s fundamental rights at a whim. Considering the rights at stake in the family court, measures need to be taken to avoid taking away a parent’s rights without the strictest scrutiny. Consistent with needing a more objective standard, the court also needs a higher threshold when applying any standard that involves such fundamental rights.

The Need for Relief from State Family Court

For many aggrieved parents, as the days turn to months and the months turn to years, the amount of time spent in the same court fighting the same issues can feel defeating. For most, it is akin to a prison sentence where the court is the prison, and the Judge is the warden. The aggrieved parent suffers repeated violations of their constitutional rights and there is no recourse to put a stop to this cruel and unusual punishment. If the standard doesn’t change and higher scrutiny isn’t enforced there is only one recourse left. That is the Writ of Habeas Corpus.

The Writ of Habeas Corpus is a fundamental tool that has long been protected to ensure individuals are not wrongfully imprisoned. The Suspension Clause of the United States Constitution holds that “The Privileges of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended unless when in Cases of Rebellion of Invasion the public Safety may require it.” (13) The United States Supreme Court has long held that the “writ of habeas corpus is the fundamental instrument for safeguarding individual freedom against arbitrary and lawless state action” and “administered with the initiative and flexibility essential to ensure that miscarriages of justice within its reach are surfaced and corrected.” (14)

This fundamental interest has been expanded over the years to allow individuals to fight against several forms of illegal state action. While the Writ of Habeas Corpus has not yet been applied in the family court system, its long overdue. Having to endure measures such as monitored visits and your child being unjustly stripped away from you, while you wade through an inefficient and unsympathetic family court system is a genuine form of imprisonment. The aggrieved parent is entrapped in a cycle of motions and delayed hearing dates all the while, they are separated from their children or forced to affirm the court’s position by subjecting them to degrading orders such as monitored visits. The very core of a parent’s life is stripped away while the wheels of injustice continue to slowly grind. Instead of protecting a parent’s right and child’s best interest, children are weaponized, and the malicious behaviors of an abusive parent are rewarded instead of punished.

As this kind of behavior continues, unchecked, individuals need a remedy outside the family court system that simply continues to imprison them. That remedy is the federal right to a Writ of Habeas Corpus. If granted, the Writ of Habeas Corpus could serve to terminate any order or procedural hindrance in the family court system preventing a parent from the custody of their child. At that point, custody would be immediately returned to both parents equally (effectively ending the imprisonment) until the family court system can provide an equitable solution. This is a necessary tool. Even more necessary if courts refuse to adopt a more objective standard and/or enforce a stricter level of scrutiny.

Conclusion

The Family Court system is broken. Monitored visits are yet another example of this broken system. Monitored visits should only be used in the rarest of occasions and only when it is absolutely necessary to protect a child from harm. However, it seems that family courts are enforcing monitored visits without this basis. Often these monitored visits have a greater detrimental and harmful impact on the parent-child relationship then if there were no visitation rights at all.

Monitored visits violate a parent’s free speech and due process constitutional rights. In addition, they do more harm than good for the child and the family dynamic as a whole. The family court system must do away with the subjective “best interests of the child” standard in favor for a standard that is objective and is designed to protect the Constitutional rights of the parent while simultaneously fostering parent-child relationships instead of severing and destroying them. Absent this, the family court system throughout the United States is in great need of a federal option to protect the Constitutional rights these state courts so often neglect.

1: Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923).

2: Troxel v. Granville, 530 U.S. 57 (2000).

3: U.S. Constitution, Amendment I.

4: U.S. Const. amend. IX.

5: U.S. Const. amend. XIV, § 1.

6: Arnold v Bd. of Ed. of Escambia County, 880 F.2d 305, 313 (11th Cir. 1989).

7: Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925).

8: Troxel v. Granville, 530 U.S. 57, at 68-9 (2000).

9: Id. at 65-6.

10: Id.

11: Troxel v. Granville, 530 U.S. 57, at 65-6 (2000).

12: Santosky v. Kramer, 455 U.S. 745 (1982).

13: United States Constitution Article I, Section 9, Clause 2.

14: Harris v. Nelson, 394 U.S. 286, 290-91 (1969).