Joe Rogan podcast guest explains ‘heart-wrenching’ source of Cobalt Used in:

electric vehicle, iPhone batteries in viral video

The Cobalt Mines (modern slaves 😢 )

A Harvard visiting professor and modern slavery activist exposed the “appalling” cobalt mining industry in the Congo on a recent episode of “The Joe Rogan Experience” that went viral. The video has already racked up over one million views and counting.

Siddharth Kara, author of “Cobalt Red: How The Blood of The Congo Powers Our Lives,” told podcast host Joe Rogan that there’s no such thing as “clean cobalt.’”

“That’s all marketing,” Kara said.

Podcast giant Joe Rogan reacted to a guest’s stories of the cobalt mining industry in a recent episode. (The Joe Rogan Experience/Spotify)

When asked by Rogan if there was any cobalt mine in the Congo that did not rely on “child labor” or “slavery,” the Harvard visiting professor told him there were none.

“I’ve never seen one and I’ve been to almost all the major industrial cobalt mines” in the country, Kara said.

One reason for that is that the demand for cobalt is exceptionally high: “Cobalt is in every single lithium, rechargeable battery manufactured in the world today,” he explained.

As a result, it’s difficult to think of a piece of technology that does not rely on cobalt to function, Kara said. “Every smartphone, every tablet, every laptop and crucially, every electric vehicle” needs the mineral.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is one of the poorest nations in the world. (AP Photo/Clarice Butsapu)

“We can’t function on a day-to-day basis without cobalt, and three-fourths of the supply is coming out of the Congo,” he added. “And it’s being mined in appalling, heart-wrenching, dangerous conditions.”

But “by and large the world doesn’t know what’s happening” in the Congo, Kara said.

“I don’t think people are aware of how horrible it is,” Rogan agreed.

The Biden administration recently entered into an agreement with the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia to bolster the green energy supply chain, despite the DRC’s documented issues with child labor.

Cobalt initially “took off because it was used in lithium-ion batteries to maximize their charge and stability,” Kara explained. “And it just so happened that the Congo is sitting on more cobalt than the rest of the planet combined,” he added.

Men work in a gold mine in Chudja, northeastern Congo, one of the areas in which so-called “conflict minerals” are mined. (AFP Photo / Lionel Healing)

As a result, the Congo, a country of roughly 90 million people, became the center of a geopolitical conflict over valuable minerals. “Before anyone knew what was happening, [the] Chinese government [and] Chinese mining companies took control of almost all the big mines and the local population has been displaced,” Kara said. Subsequently, the Congolese are “under duress.”

British rapper Zuby recommended that his nearly one million followers watch the interview.

“This latest Joe Rogan Experience podcast is heavy,” he wrote. “If you have a smartphone or electric vehicle (that’s 100% of you) then I strongly recommend listening to it.”

Some, if not all, of the famous tech and energy companies in the world are implicated in the humanitarian crisis, Kara said.

“This is the bottom of the supply chain of your iPhone, of your Tesla, of your Samsung,” he asserted.

Fox News’ Thomas Catenacci contributed to this report.

DRC’s ‘artisanal’ cobalt mines tainted by lack of compliance

By Rédaction Africanews with AFP

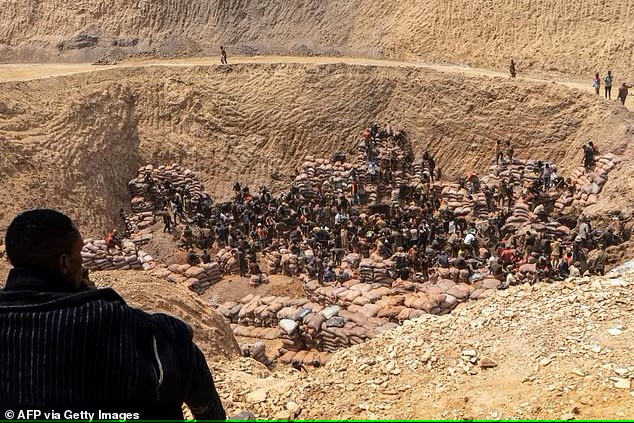

In a huge pit in Shabara in south-eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, thousands of illegal miners work daily to dig out rocks containing the speckled blue-gold ore, cobalt.

The country holds over 70 per cent of world supply of this key ingredient in rechargeable batteries, electric cars, and mobile phones.

It is estimated that some 200,000 people works as informal diggers in country’s cobalt mines in flagrant violation of its laws.

Artisanal miners breaking the law

The mining at Shabara has been carrying on for years in defiance of the site’s owner, a subsidiary of mining and commodities giant, Glencore.

So-called artisanal miners says they can make equivalent of $200 on a good week, which is a small fortune in a country where most live on under $2 a day.

‘Here, we’re independent, everyone comes, works independently, goes to sell the ore at the trading centre, and makes money. Compared to other mining areas where I’ve worked, here I work in order,’ says Antoine Dela wa Monga.

But the sector’s image is tainted by artisanal mining, with accusations of child labour, dangerous working conditions, and corruption.

‘Normally, when you produce and export, you have to pay a fee. But when it is not declared, nothing can be paid on it. Hence the importance of being able to set up procedures that can guarantee traceability from upstream to downstream, to ensure that these flows become compliant,’ says Tosi Mpanu Mpanu, who is working on the formalisation of artisanal cobalt mining.

Need to clean up the sector’s image

However, government attempts to clear up the illegal mines are at a near standstill.

David Sturmes, director of corporate engagement and strategic partnerships at Fair Cobalt Alliances, says the situation is a lose-lose one for all.

‘Artisanal mining occurs on industrial concessions, so legally speaking, they are infringing on industrial miners territory. This makes it difficult for industrial miners to engage. The mining code doesn’t allow for them to purchase from artisanal miners or allow them on their concessions, but international human rights conventions don’t allow them to kick them off either.’

Under Congolese law, artisanal diggers are only allowed to work in government-designated zones and as part of approved cooperatives. But most diggers say the designated areas are unviable and prefer to work on industrial concessions with identified deposits.

Despite fluctuations in global prices, analysts say the metal’s future is strong given demand from the energy transition.

Sturmes says this means that mining firms and the illegal diggers share a common interest in cleaning up Congolese cobalt’s tainted image.