Anti-SLAPP Law in California

1st Amendment Freedom of Press & Speech

What is Anti-SLAPP?

Short for strategic lawsuits against public participation, SLAPPs have become an all-too-common tool for intimidating and silencing criticism through expensive, baseless legal proceedings.

Anti-SLAPP laws are meant to provide a remedy to SLAPP suits. Anti-SLAPP laws are intended to prevent people from using courts, and potential threats of a lawsuit, to intimidate people who are exercising their First Amendment rights. In terms of reporting, news organizations and individual journalists can use anti-SLAPP statutes to protect themselves from the financial threat of a groundless defamation case brought by a subject of an enterprise or investigative story.

Under most anti-SLAPP statutes, the person sued makes a motion to strike the case because it involves speech on a matter of public concern. The plaintiff then has the burden of showing a probability that they will prevail in the suit — meaning they must show that they have evidence that could result in a favorable verdict. If the plaintiff cannot meet this burden and the suit is dismissed through anti-SLAPP proceedings, many statutes allow defendants to collect attorney’s fees from the plaintiff.

Resources

Anti-SLAPP Stories

State-by-State Resources

View the Reporters Committee’s Anti-SLAPP Legal Guide.

Recent Anti-SLAPP Updates

2019-06-03: Colorado became 31st state with anti-SLAPP protections

2019-06-02: Texas modified its existing anti-SLAPP law

2019-04-23: The Tennessee legislature amended an anti-SLAPP statute that significantly strengthens the state’s anti-SLAPP protections. Effective July 1, 2019, the new Tennessee Public Participation Act allows defendants to file a motion to dismiss a SLAPP suit before the costly discovery process begins, appeal the denial of an anti-SLAPP motion, and recover attorney’s fees if a court rules in their favor. The new law is largely based on Texas’ anti-SLAPP statute. cited https://www.rcfp.org/resources/anti-slapp-laws/

Cases Involving the California Anti-SLAPP Law

Lawsuits seeking to curtail the exercise of the First Amendment can take a multitude of forms. The cases on the following pages generally involve a special motion to strike a complaint and/or motion for attorney fees and costs pursuant to the California anti-SLAPP law, Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16.

CA Statutes

The California anti-SLAPP law was enacted by the state Legislature almost twenty years ago to protect the petition and free speech rights of all Californians. Amendments have been made since that time to improve the law and provide stronger protection from meritless lawsuits to anyone who is SLAPPed in California.

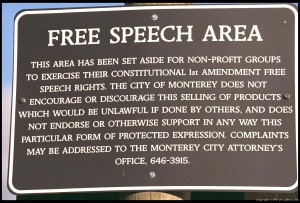

Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16 Statements before a government body or official proceeding; or in connection with issue under consideration by government body; or in a place open to the public or public forum in connection with issue of public interest; or any other conduct in furtherance of petition/free speech in connection with issue of public interest, are protected. California’s anti-SLAPP statute provides for a special motion to strike a complaint where the complaint arises from activity exercising the rights of petition and free speech. The statute was first enacted in 1992.

Code of Civil Procedure section 425.17 Exempts from the anti-SLAPP law public interest litigation and claims arising from commercial speech. This statute was enacted to correct abuse of the anti-SLAPP statute (CCP § 425.16). It prohibits anti-SLAPP motions in response to (1) public interest litigation when certain conditions are met, and (2) certain actions against a business that arise from commercial statements or conduct of the business.

Code of Civil Procedure section 425.18

SLAPPbacks: Prohibits the use of certain provisions of the anti-SLAPP law against a SLAPPback brought in the form of a malicious prosecution claim. This statute was enacted primarily to facilitate the recovery by SLAPP victims of their damages through a SLAPPback (malicious prosecution action) against the SLAPP filers and their attorneys after the underlying SLAPP has been dismissed. It provides that the prevailing defendant attorney fee and immediate appeal provisions of the anti-SLAPP law do not apply to SLAPPbacks, and that an anti-SLAPP motion may not be filed against a SLAPPback by a party whose filing or maintenance of the prior cause of action from which the SLAPPback arises was illegal as a matter of law.

Code of Civil Procedure sections 1987.1 and 1987.2

These statutes set forth a procedure for challenging subpoenas. The 2008 amendment to section 1987.1 allows any person to challenge subpoenas for “personally identifying information” sought in connection with an underlying lawsuit involving that person’s exercise of free speech rights. This amendment also added section 1987.2(b), which provides that such a person who successfully challenges such a subpoena arising from a lawsuit filed in another state based on exercise of free speech rights on the Internet is entitled to recover his or her attorney fees.

Defines privileged publication or broadcast and immunizes participants in official proceedings or litigation against all tort actions except malicious prosecution. This statute figures prominently in many cases. Check back soon for links to some cases arising from this law.

The California Anti-Libel Tourism Act

SB 320 passed both chambers of the CA legislature and was approved by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger on 10/11/09. The bill prohibits recognition of foreign defamation judgments if a California court determines that the defamation law applied by a foreign court does not provide at least as much protection for freedom of speech and the press as provided by both the United States and California Constitutions.

U.S. Federal Statutes

Communications Decency Act (CDA 230), U.S. Code 47 section 230

Grants interactive online services of all types, including news websites, blogs, forums, and listservs, broad immunity from certain types of legal liability stemming from content created by others

Bottom Line:

-

Courts consistently protect speech that is disturbing, rude, mean, or cruel, as long as it’s not false.

-

Anti-SLAPP laws in California and elsewhere make it easier to dismiss lawsuits that try to punish this kind of harsh commentary.

-

The more the subject involves public interest, the stronger the protection.

Anti-SLAPP Legal Guide

Anti-SLAPP laws provide defendants a way to quickly dismiss meritless lawsuits — known as SLAPPs or strategic lawsuits against public participation — filed against them for exercising speech, press, assembly, petition, or association rights. These laws aim to discourage the filing of SLAPP suits and prevent them from imposing significant litigation costs and chilling protected speech.

In recent years, several states have adopted or amended their anti-SLAPP laws. As of January 2025, 35 states and the District of Columbia have anti-SLAPP laws, including Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington.

Anti-SLAPP protections vary significantly from state to state. For example, in some states, like Massachusetts, they only protect defendants from cases brought in retaliation for petitioning the government. In others, such as California, the laws broadly protect speech made in connection with a public issue. For the most part, anti-SLAPP laws are broad enough to cover SLAPP suits aimed at silencing or retaliating against journalists or news outlets for critical reporting. These laws typically provide critical protections to the news media—allowing defendants to secure a quick dismissal before the costly discovery process begins, permitting defendants who win their anti-SLAPP motions to recover attorney’s fees and costs, automatically staying discovery once the defendant has filed an anti-SLAPP motion, and allowing defendants to immediately appeal a trial court’s denial of an anti-SLAPP motion.

This anti-SLAPP legal guide provides a general introduction to each state’s anti-SLAPP law, to the extent one exists. It does not replace the legal advice of an attorney in one’s own state when confronted with a specific legal problem. Journalists who have additional questions or need assistance finding a lawyer with experience litigating these types of claims can contact the Reporters Committee’s hotline.

Special thanks to Laura Prather, a partner at Haynes and Boone, for her assistance with the original version of this guide, and Austin Vining, a law student and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Florida, class of 2021, for his assistance in updating this guide. source

California has a strong anti-SLAPP law.

California has a strong anti-SLAPP law. To challenge a SLAPP suit in California, defendants must show that they are being sued for “any act . . . in furtherance of the person’s right of petition or free speech under the United States Constitution or the California Constitution in connection with a public issue.” Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16 (2019). Under the statute, the rights of free speech or petition in connection with a public issue include four categories of activities: statements made before a legislative, executive or judicial proceeding; statements made in connection with an issue under consideration by a governmental body; statements made in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest; and any other conduct in furtherance of the exercise of free speech or petition rights in connection with “a public issue or an issue of public interest.” § 425.16(e).

California courts consider several factors when evaluating whether a statement relates to an issue of public interest, including whether the subject of the statement at issue was a person or entity in the public eye, whether the statement involved conduct that could affect large numbers of people beyond the direct participants, and whether the statement contributed to debate on a topic of widespread public interest. Rivero v. Am. Fed’n of State, Cty., & Mun. Emps., 130 Cal. Rptr. 2d 81, 89–90 (Cal. Ct. App. 2003). Under this standard, statements that report or comment on controversial political, economic, and social issues, from the local to the international level, would certainly qualify. Conversely, a California court has held that statements about a person who was not in the public eye did not relate to an issue of public interest. Dyer v. Childress, 55 Cal. Rptr. 3d 544 (Cal. Ct. App. 2007).

The California anti-SLAPP law allows a defendant to file a motion to strike the complaint, which the court will hear within 30 days unless the docket is overbooked. Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16(f). Discovery activities are placed on hold from the time the motion is filed until the court has ruled on it, although the judge may permit “specified discovery” if the requesting party provides notice of its request to the other side and can show good cause for it. § 425.16(g).

In ruling on the motion to strike, a California court will first determine whether the defendant established that the lawsuit arose from one of the statutorily defined protected speech or petition activities. Braun v. Chronicle Publ’g Co., 61 Cal. Rptr. 2d 58 (Cal. Ct. App. 1997). If that is the case, the judge will grant the motion unless the plaintiff can show a probability that he will prevail on the claim. Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16(b)(1). In making this determination, the court will consider the plaintiff’s complaint, the SLAPP defendant’s motion to strike, and any sworn statements containing facts on which the assertions in those documents are based. § 425.16(b)(2).

If the court grants the motion to strike, it must impose attorney’s fees and costs on the plaintiff, except when the basis for the lawsuit stemmed from California’s public records or open meetings laws. Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16(c)(1)-(2). These laws provide separate provisions for recovering attorney’s fees and costs.

The California anti-SLAPP law also gives a successful defendant who can show that the plaintiff filed the lawsuit to harass or silence the speaker the ability to file a so-called “SLAPPback” lawsuit against his or her opponent. § 425.18. Under this remedy, a SLAPP defendant who won a motion to strike may sue the plaintiff who filed the SLAPP suit to recover damages for abuse of the legal process. Conversely, the defendant must pay the plaintiff’s attorney’s fees and costs if the court finds that the motion to strike was frivolous or brought solely to delay the proceedings. § 425.16(c)(1).

Either party is entitled to immediately appeal the court’s decision on the motion to strike. § 425.16(i).

To learn more, read San Francisco Superior Court Judge Curtis Karnow’s “decision-tree,” depicting how anti-SLAPP motions are processed in California. find your state here all 50 included!

learn more about Anti-SLAPP:

California Supreme Court Confirms that the “anti-SLAPP” Statute Applies to Claims of Discrimination and Retaliation

Malicious Prosecution Actions Arising Out Of Family Law Proceedings: Proceed Carefully

California has an excellent anti-SLAPP law. It was enacted in 2009.

Frankly, the procedural requirements of section 425.16, its interaction with other statutes such as Civil Code 47 (the statute defining what is privileged speech), and the latest definition of “public interest,” which changes regularly, is often far too challenging for a trial court judge to decipher in the limited time he or she has to consider an anti-SLAPP motion.

A bad decision by the judge can be devastating to the defendant or plaintiff. If the special motion to strike is denied when it should have been granted, then the defendant remains hostage to the action. In an effort to minimize this possibility, the statute provides that the order denying the motion is immediately appealable, but that is costly and time-consuming, which is what the anti-SLAPP statute was trying to prevent in the first place. Conversely, improperly (or properly) granting an anti-SLAPP motion will entitle the defendant to a mandatory award of reasonable attorney fees. This has turned into a significant problem because there are many unethical attorneys who submit inflated fee applications following a successful anti-SLAPP motion. I am frequently retained to testify as an expert to challenge these inflated bills, and thus far I have always been successful in having them reduced, but without such testimony far too many judges are rubber-stamping attorney fee motions, which I have seen exceed $400,000. And there are no “take-backs” when it comes to SLAPP suits. Once an anti-SLAPP motion has been filed, a plaintiff cannot escape this mandatory fee award by amending or even dismissing his complaint.

Any of the following types of actions (and perhaps more because the law is expanding) can be a SLAPP suit:

- Defamation

- Malicious Prosecution or Abuse of Process

- Nuisance

- Invasion of Privacy

- Conspiracy

- Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress

- Interference with Contract or Economic Advantage

As you can see, many actions can result in an anti-SLAPP motion, and such a motion can be a costly and inequitable minefield if the judge fails to fully understand the law. If you are going to enter that minefield, you need an attorney who is a recognized expert in this field. You need Morris & Stone, attorneys whose primary area of practice is defamation (slander and libel) and the accompanying SLAPP laws.

1In state courts, claims may not be amended if an anti-SLAPP motion is pending or has been granted. In federal courts, leave to amend may be granted.

Statements before a government body or official proceeding; or in connection with issue under consideration by government body; or in a place open to the public or public forum in connection with issue of public interest; or any other conduct in furtherance of petition/free speech in connection with issue of public interest, are protected.

Exempts from the anti-SLAPP law public interest litigation and claims arising from commercial speech.

SLAPPbacks: Prohibits the use of certain provisions of the anti-SLAPP law against a SLAPPback brought in the form of a malicious prosecution claim.

The California Anti-Libel Tourism Act

SB 320 passed both chambers of the CA legislature and was approved by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger on 10/11/09. The bill prohibits recognition of foreign defamation judgments if a California court determines that the defamation law applied by a foreign court does not provide at least as much protection for freedom of speech and the press as provided by both the United States and California Constitutions. source

Anti Slapp Law Resources:

Anti-SLAPP and Free Speech in Defamation & Emotional Distress Cases

SOME GOOD 1ST AMENDMEND ANTI SLAPP LAW FOR YOU SISSY’S:

-

Anti-SLAPP Law Cases – Case Law Summaries & Citings

https://goodshepherdmedia.net/anti-slapp-law-cases-case-law-summaries-citings/

-

Anti-SLAPP Law in California

-

Court tosses disbarred lawyer’s suit over newspaper article

https://goodshepherdmedia.net/court-tosses-disbarred-lawyers-suit-over-newspaper-article/

California’s Anti-SLAPP Law and Related State and Federal Statutes

CA Statutes

The California anti-SLAPP law was enacted by the state Legislature almost twenty years ago to protect the petition and free speech rights of all Californians. Amendments have been made since that time to improve the law and provide stronger protection from meritless lawsuits to anyone who is SLAPPed in California.

Code of Civil Procedure section 425.16

California’s anti-SLAPP statute provides for a special motion to strike a complaint where the complaint arises from activity exercising the rights of petition and free speech. The statute was first enacted in 1992.

Code of Civil Procedure section 425.17

This statute was enacted to correct abuse of the anti-SLAPP statute (CCP § 425.16). It prohibits anti-SLAPP motions in response to (1) public interest litigation when certain conditions are met, and (2) certain actions against a business that arise from commercial statements or conduct of the business.

Code of Civil Procedure section 425.18

This statute was enacted primarily to facilitate the recovery by SLAPP victims of their damages through a SLAPPback (malicious prosecution action) against the SLAPP filers and their attorneys after the underlying SLAPP has been dismissed. It provides that the prevailing defendant attorney fee and immediate appeal provisions of the anti-SLAPP law do not apply to SLAPPbacks, and that an anti-SLAPP motion may not be filed against a SLAPPback by a party whose filing or maintenance of the prior cause of action from which the SLAPPback arises was illegal as a matter of law.

Code of Civil Procedure sections 1987.1 and 1987.2

These statutes set forth a procedure for challenging subpoenas. The 2008 amendment to section 1987.1 allows any person to challenge subpoenas for “personally identifying information” sought in connection with an underlying lawsuit involving that person’s exercise of free speech rights. This amendment also added section 1987.2(b), which provides that such a person who successfully challenges such a subpoena arising from a lawsuit filed in another state based on exercise of free speech rights on the Internet is entitled to recover his or her attorney fees.

Defines privileged publication or broadcast and immunizes participants in official proceedings or litigation against all tort actions except malicious prosecution. This statute figures prominently in many cases. Check back soon for links to some cases arising from this law.

U.S. Federal Statutes

Communications Decency Act (CDA 230), U.S. Code 47 section 230

Grants interactive online services of all types, including news websites, blogs, forums, and listservs, broad immunity from certain types of legal liability stemming from content created by others. source

Code of Civil Procedure – Section 425.16 California’s Anti-SLAPP Law

Code of Civil Procedure – Section 425.16.

- (a) The Legislature finds and declares that there has been a disturbing increase in lawsuits brought primarily to chill the valid exercise of the constitutional rights of freedom of speech and petition for the redress of grievances. The Legislature finds and declares that it is in the public interest to encourage continued participation in matters of public significance, and that this participation should not be chilled through abuse of the judicial process. To this end, this section shall be construed broadly.

- (b)

- (1) A cause of action against a person arising from any act of that person in furtherance of the person’s right of petition or free speech under the United States Constitution or the California Constitution in connection with a public issue shall be subject to a special motion to strike, unless the court determines that the plaintiff has established that there is a probability that the plaintiff will prevail on the claim.

- (2) In making its determination, the court shall consider the pleadings, and supporting and opposing affidavits stating the facts upon which the liability or defense is based.

- (3) If the court determines that the plaintiff has established a probability that he or she will prevail on the claim, neither that determination nor the fact of that determination shall be admissible in evidence at any later stage of the case, or in any subsequent action, and no burden of proof or degree of proof otherwise applicable shall be affected by that determination in any later stage of the case or in any subsequent proceeding.

- (c)

- (1) Except as provided in paragraph

- (2), in any action subject to subdivision (b), a prevailing defendant on a special motion to strike shall be entitled to recover his or her attorney’s fees and costs. If the court finds that a special motion to strike is frivolous or is solely intended to cause unnecessary delay, the court shall award costs and reasonable attorney’s fees to a plaintiff prevailing on the motion, pursuant to Section 128.5. (2) A defendant who prevails on a special motion to strike in an action subject to paragraph (1) shall not be entitled to attorney’s fees and costs if that cause of action is brought pursuant to Section 6259, 11130, 11130.3, 54960, or 54960.1 of the Government Code. Nothing in this paragraph shall be construed to prevent a prevailing defendant from recovering attorney’s fees and costs pursuant to subdivision (d) of Section 6259, 11130.5, or 54690.5.

- (d) This section shall not apply to any enforcement action brought in the name of the people of the State of California by the Attorney General, district attorney, or city attorney, acting as a public prosecutor.

- (e) As used in this section, “act in furtherance of a person’s right of petition or free speech under the United States or California Constitution in connection with a public issue” includes:

- (1) any written or oral statement or writing made before a legislative, executive, or judicial proceeding, or any other official proceeding authorized by law,

- (2) any written or oral statement or writing made in connection with an issue under consideration or review by a legislative, executive, or judicial body, or any other official proceeding authorized by law,

- (3) any written or oral statement or writing made in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest, or

- (4) any other conduct in furtherance of the exercise of the constitutional right of petition or the constitutional right of free speech in connection with a public issue or an issue of public interest.

- (f) The special motion may be filed within 60 days of the service of the complaint or, in the court’s discretion, at any later time upon terms it deems proper. The motion shall be scheduled by the clerk of the court for a hearing not more than 30 days after the service of the motion unless the docket conditions of the court require a later hearing.

- (g) All discovery proceedings in the action shall be stayed upon the filing of a notice of motion made pursuant to this section. The stay of discovery shall remain in effect until notice of entry of the order ruling on the motion. The court, on noticed motion and for good cause shown, may order that specified discovery be conducted notwithstanding this subdivision.

- (h) For purposes of this section, “complaint” includes “cross-complaint” and “petition,” “plaintiff” includes “cross-complainant” and “petitioner,” and “defendant” includes “cross-defendant” and “respondent.”

- (i) An order granting or denying a special motion to strike shall be appealable under Section 904.1.

- (j)

- (1) Any party who files a special motion to strike pursuant to this section, and any party who files an opposition to a special motion to strike, shall, promptly upon so filing, transmit to the Judicial Council, by e-mail or facsimile, a copy of the endorsed, filed caption page of the motion or opposition, a copy of any related notice of appeal or petition for a writ, and a conformed copy of any order issued pursuant to this section, including any order granting or denying a special motion to strike, discovery, or fees.

- (2) The Judicial Council shall maintain a public record of information transmitted pursuant to this subdivision for at least three years, and may store the information on microfilm or other appropriate electronic media.

History of statute:

1992 — Senate Bill 264 (Lockyer). For a list of organizations and newspapers that supported enactment of the original statute, see Supporters of 1992 Anti-SLAPP Bill.

1993 — The statute was amended to require award of costs and attorney fees to the plaintiff if the court finds that a special motion to strike is frivolous or solely intended to cause unnecessary delay.

1997 — Senate Bill 1296 (Lockyer). The statute was amended in light of appellate court opinions that had narrowly construed application of the statute to disputes involving matters of “public interest”. In amending the statute, the Legislature clarified its intent that any conduct in furtherance of the rights of petition or free speech is protected under the anti-SLAPP law.

1999 — Assembly Bill 1675 (Assembly Judiciary Committee). Under the original statute, a defendant whose special motion to strike a complaint was denied could challenge the denial only through a petition for a writ in the Court of Appeal. Writs are discretionary, disfavored, and rarely successful. If, however, a plaintiff’s complaint were dismissed pursuant to a special motion to strike, the plaintiff was able to appeal the dismissal immediately. Thus, the statute was amended to give the SLAPP target — the person whom the anti-SLAPP law was designed to protect — the same ability as the filer of the SLAPP to challenge an adverse trial court decision. See also Supporters of AB 1675.

2005 — Assembly Bill 1158 (Lieber). The statute was amended to overrule the decision by the California Supreme Court in Wilson v. Parker, Covert & Chidester (2002) 28 Cal.4th 811, which held that the trial court’s erroneous denial of an anti-SLAPP motion constitutes probable cause for filing and maintaining a SLAPP, as well as the decisions in Decker v. The U.D. Registry, Inc.(2003) 105 Cal.App.4th 1382, and Fair Political Practices Commission v. American Civil Rights Coalition, Inc. (2004) 121 Cal.App.4th 1171, which held that the 30-day period in which to schedule a hearing on an anti-SLAPP motion is jurisdictional.

2009 — The statute was amended to add section 425.16(c)(2), which provides that a defendant who prevails on an anti-SLAPP motion may not be awarded fees on claims of violation of the public records act or open meetings law. cited source

Anti-SLAPP Law in California

Note: This page covers information specific to California. For general information concerning Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs), see the overview section of this guide.

You can use California’s anti-SLAPP statute to counter a SLAPP suit filed against you. The statute allows you to file a special motion to strike a complaint filed against you based on an “act in furtherance of [your] right of petition or free speech under the United States or California Constitution in connection with a public issue.” Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16. If a court rules in your favor, it will dismiss the plaintiff’s case early in the litigation and award you attorneys’ fees and court costs. In addition, if a party to a SLAPP suit seeks your personal identifying information, California law allows you to make a motion to quash the discovery order, request, or subpoena.

Activities Covered By The California Anti-SLAPP Statute

Not every unwelcome lawsuit is a SLAPP. In California, the term applies to lawsuits brought primarily to discourage speech about issues of public significance or public participation in government proceedings. To challenge a lawsuit as a SLAPP, you need to show that the plaintiff is suing you for an “act in furtherance of [your] right of petition or free speech under the United States or California Constitution in connection with a public issue.” Although people often use terms like “free speech” and “petition the government” loosely in popular speech, the anti-SLAPP law gives this phrase a particular legal meaning, which includes four categories of activities:

- any written or oral statement or writing made before a legislative, executive, or judicial proceeding, or any other official proceeding authorized by law;

- any written or oral statement or writing made in connection with an issue under consideration or review by a legislative, executive, or judicial body, or any other official proceeding authorized by law;

- any written or oral statement or writing made in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest; or

- any other conduct in furtherance of the exercise of the constitutional right of petition or the constitutional right of free speech in connection with a public issue or an issue of public interest.

Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16(e)(1-4). As an online publisher, you are most likely to rely on the third category above, which applies to a written statement in a public forum on an issue of public interest.

Under California law, a publicly accessible website is considered a public forum. See Barrett v. Rosenthal, 146 P.3d 510, 514 n.4 (Cal. 2006). The website does not have to allow comments or other public participation, so long as it is publicly available over the Internet. See Wilbanks v. Wolk, 121 Cal. App. 4th 883, 897 (Cal. Ct. App. 2001).

Many different kinds of statements may relate to an issue of public interest. California courts look at factors such as whether the subject of the disputed statement was a person or entity in the public eye, whether the statement involved conduct that could affect large numbers of people beyond the direct participants, and whether the statement contributed to debate on a topic of widespread public interest. Certainly, statements educating the public about or taking a position on a controversial issue in local, state, national, or international politics would qualify. Some other examples include:

- Statements about the character of a public official, see Vogel v. Felice, 127 Cal. App. 4th 1006 (2005);

- Statements about the financial solvency of a large institution, such as a hospital, see Integrated Healthcare Holdings, Inc. v. Fitzgibbons, 140 Cal. App. 4th 515, 523 (2006);

- Statements about a celebrity, or a person voluntarily associating with a celebrity, see Ronson v. Lavandeira, BC 374174 (Cal. Super. Ct. Nov. 1, 2007);

- Statements about an ideological opponent in the context of debates about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, see Neuwirth v. Silverstein, SC 094441 (Cal. Super. Ct. Nov. 27, 2007); and

- Statements about the governance of a homeowners association, see Damon v. Ocean Hills Journalism Club, 85 Cal. App. 4th 468 (2000).

In contrast, California courts have found other statements to be unrelated to an issue of public interest, including:

- statements about the character of a person who is not in the public eye, see Dyer v. Childress, 147 Cal. App. 4th 1273, 1281 (2007); and

- statements about the performance of contractual obligations or other private interests, see Ericsson GE Mobile Communs. v. C.S.I. Telcoms. Eng’rs. 49 Cal. App. 4th 1591 (1996).

Although the anti-SLAPP statute is meant to prevent lawsuits from chilling speech and discouraging public participation, you do not need to show that the SLAPP actually discouraged you from participating or speaking out. Nor do you need to show that the plaintiff bringing the SLAPP intended to restrict your free speech.

Protections for Personal Identifying Information Sought in a SLAPP suit

In addition to providing a motion to strike, California law also allows a person whose identifying information is sought in connection with a claim arising from act in exercise of anonymous free speech rights to file a motion to quash — that is, to void or modify the subpoena seeking your personal identifying information so you do not have to provide that information. Cal. Civ. Pro. Code § 1987.1.

How To Use The California Anti-SLAPP Statute

The California anti-SLAPP statute gives you the ability to file a motion to strike (i.e., to dismiss) a complaint brought against you for engaging in protected speech or petition activity (discussed above). If you are served with a complaint that you believe to be a SLAPP, you should seek legal assistance immediately. Successfully filing and arguing a motion to strike can be complicated, and you and your lawyer need to move quickly to avoid missing important deadlines. You should file your motion to strike under the anti-SLAPP statute within sixty days of being served with the complaint. A court may allow you to file the motion after sixty days, but there is no guarantee that it will do so. Keep in mind that, although hiring legal help is expensive, you can recover your attorneys’ fees if you win your motion.

One of the benefits of the anti-SLAPP statute is that it enables you to get the SLAPP suit dismissed quickly. When you file a motion to strike, the clerk of the court will schedule a hearing on your motion within thirty days after filing. Additionally, once you file your motion, the plaintiff generally cannot engage in “discovery” — that is, the plaintiff generally may not ask you to produce documents, sit for a deposition, or answer formal written questions, at least not without first getting permission from the court.

In ruling on a motion to strike, a court will first consider whether you have established that the lawsuit arises out of a protected speech or petition activity (discussed above). Assuming you can show this, the court will then require the plaintiff to introduce evidence supporting the essential elements of its legal claim. Because a true SLAPP is not meant to succeed in court, but only to intimidate and harass, a plaintiff bringing such a lawsuit will not be able to make this showing, and the court will dismiss the case. On the other hand, if the plaintiff’s case is strong, then the court will not grant your motion to strike, and the lawsuit will move ahead like any ordinary case.

If the court denies your motion to strike, you are entitled to appeal the decision immediately.

In addition to creating the motion to strike, the statute also allows a person whose personal identifying information is sought in connection with a claim arising from act in exercise of anonymous free speech rights to file a motion to quash — that is, to void or terminate the subpoena, request, or discovery order seeking your personal identifying information so you do not have to provide that information.

When you make your motion to quash, the court “may” grant your request if it is “reasonably made.” In reviewing your motion, the court will probably require the plaintiff to make a prima facie showing, meaning he or she must present evidence to support all of the elements of the underlying claim (or, at least, all of the elements within the plaintiff’s control). See Krinsky v. Doe 6, 159 Cal. App. 4th 1154, 1171 fn. 12 (Cal. App. 6 Dist. 2008). If the plaintiff cannot make that showing, the court will probably quash the subpoena and keep your identity secret.

If you are served with a SLAPP in California, you can report it to the California Anti-SLAPP Project and request assistance. The California Anti-SLAPP Project also has two excellent guides on dealing with a SLAPP suit in California, Survival Guide for SLAPP Victims and Defending Against A SLAPP. In addition, the First Amendment Project has an excellent step-by-step guide to the legal process of defending against a SLAPP in California.

What Happens If You Win A Motion To Strike

If you prevail on a motion to strike under California’s anti-SLAPP statute, the court will dismiss the lawsuit against you, and you will be entitled to recover your attorneys’ fees and court costs. See Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16(c).

Additionally, if you win your motion to strike and believe that you can show that the plaintiff filed the lawsuit in order to harass or silence you rather than to resolve a legitimate legal claim, then consider filing a “SLAPPback” suit against your opponent. A “SLAPPback” is a lawsuit you can bring against the person who filed the SLAPP suit to recover compensatory and punitive damages for abuse of the legal process. See Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.18 (setting out certain procedural rules for “SLAPPback” suits). Section 425.18 contemplates bringing a SLAPPback in a subsequent lawsuit after the original SLAPP has been dismissed, but you might be able to bring a SLAPPback as a counterclaim in the original lawsuit. You should not underestimate the considerable expense required to bring a SLAPPback, like any lawsuit, to a successful conclusion.

If your successful motion to quash arises out of a lawsuit filed in a California court, the judge has discretion to award expenses incurred in making the motion. The court will award fees if the plaintiff opposed your motion “in bad faith or without substantial justification,” or if at least one part of the subpoena was “oppressive.” Cal. Civ. Pro. Code § 1987.2(a). But note that if you lose your motion to quash, and the court decides that your motion was made in bad faith, you may have to pay the plaintiff’s costs of opposing the motion.

If you successfully quash a California identity-seeking subpoena that relates to a lawsuit filed in another state, the court “shall” award all reasonably expenses incurred in making your motion – including attorneys’ fees – if the following conditions are met:

- the subpoena was served on an Internet service provider or other Section 230 computer service provider;

- the underlying lawsuit arose from your exercise of free speech on the Internet; and

- the plaintiff failed to make his prima facie showing.

Cal. Civ. Pro. Code § 1987.2(b). Jurisdiction: California Subject Area: SLAPP cited https://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/anti-slapp-law-california

California Has a Very Strong Anti-SLAPP Law. California Anti-SLAPP Law

California Anti-SLAPP Law

California courts consider several factors when evaluating whether a statement relates to an issue of public interest, including whether the subject of the statement at issue was a person or entity in the public eye, whether the statement involved conduct that could affect large numbers of people beyond the direct participants, and whether the statement contributed to debate on a topic of widespread public interest. Rivero v. Am. Fed’n of State, Cty., & Mun. Emps., 130 Cal. Rptr. 2d 81, 89–90 (Cal. Ct. App. 2003). Under this standard, statements that report or comment on controversial political, economic, and social issues, from the local to the international level, would certainly qualify. Conversely, a California court has held that statements about a person who was not in the public eye did not relate to an issue of public interest. Dyer v. Childress, 55 Cal. Rptr. 3d 544 (Cal. Ct. App. 2007).

The California anti-SLAPP law allows a defendant to file a motion to strike the complaint, which the court will hear within 30 days unless the docket is overbooked. Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16(f). Discovery activities are placed on hold from the time the motion is filed until the court has ruled on it, although the judge may permit “specified discovery” if the requesting party provides notice of its request to the other side and can show good cause for it. § 425.16(g).

In ruling on the motion to strike, a California court will first determine whether the defendant established that the lawsuit arose from one of the statutorily defined protected speech or petition activities. Braun v. Chronicle Publ’g Co., 61 Cal. Rptr. 2d 58 (Cal. Ct. App. 1997). If that is the case, the judge will grant the motion unless the plaintiff can show a probability that he will prevail on the claim. Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16(b)(1). In making this determination, the court will consider the plaintiff’s complaint, the SLAPP defendant’s motion to strike, and any sworn statements containing facts on which the assertions in those documents are based. § 425.16(b)(2).

If the court grants the motion to strike, it must impose attorney’s fees and costs on the plaintiff, except when the basis for the lawsuit stemmed from California’s public records or open meetings laws. Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16(c)(1)-(2). These laws provide separate provisions for recovering attorney’s fees and costs.

The California anti-SLAPP law also gives a successful defendant who can show that the plaintiff filed the lawsuit to harass or silence the speaker the ability to file a so-called “SLAPPback” lawsuit against his or her opponent. § 425.18. Under this remedy, a SLAPP defendant who won a motion to strike may sue the plaintiff who filed the SLAPP suit to recover damages for abuse of the legal process. Conversely, the defendant must pay the plaintiff’s attorney’s fees and costs if the court finds that the motion to strike was frivolous or brought solely to delay the proceedings. § 425.16(c)(1).

Either party is entitled to immediately appeal the court’s decision on the motion to strike. § 425.16(i).

To learn more, read San Francisco Superior Court Judge Curtis Karnow’s “decision-tree,” depicting how anti-SLAPP motions are processed in California. source

California Anti-SLAPP Caselaw

Recent Developments in California Anti-SLAPP Case Law, Summer 2021

This alert surveys recent case law and legislative developments involving California’s anti-SLAPP statute, California Code of Civil Procedure § 425.16(e). The anti-SLAPP statute offers defendants in actions brought pursuant to California law a powerful procedural tool to seek early dismissal of lawsuits that target defendants’ actions taken in furtherance of their “right of petition or free speech under the United States Constitution or the California Constitution in connection with a public issue.”[1]

Courts apply a two-pronged analytical framework to evaluate an anti-SLAPP special motion to strike. The first is the “protected activity” prong, under which the defendant has the burden of proving that the activity that gave rise to the plaintiff’s cause of action arises from one of the four enumerated categories under § 425.16(e):

- any written or oral statement or writing made before a legislative, executive, or judicial proceeding, or any other official proceeding authorized by law,

- any written or oral statement or writing made in connection with an issue under consideration or review by a legislative, executive, or judicial body, or any other official proceeding authorized by law,

- any written or oral statement or writing made in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest, or

- any other conduct in furtherance of the exercise of the constitutional right of petition or the constitutional right of free speech in connection with a public issue or an issue of public interest.

If the first prong is met, the burden shifts to the plaintiff to establish on the second prong that “there is a probability that the plaintiff will prevail on the claim.”[2] Giving additional teeth to the law, a defendant who prevails on an anti-SLAPP special motion to strike is entitled to recover its attorneys’ fees and costs incurred in bringing the motion.[3]

Below, we discuss recent substantive decisions by state and federal courts that apply the anti-SLAPP statute’s framework to lawsuits in the media, finance, employment, and real estate contexts and which involve claims regarding revenge porn, trade libel, unfair competition, business torts, and employment discrimination, and also implicate the law’s commercial-speech exemption.

1. Hill v. Heslep et al., Case No. 20STCV48797 (Apr. 7, 2021, L.A. Cnty. Super. Ct.)

Facts: Plaintiff Katherine Hill, a former U.S. Representative from California’s 25th congressional district, sued Mail Media, Inc. (publisher of the Daily Mail) in a California state court for publishing to its MailOnline website nonconsensually distributed nude photographs of Hill.[4] The photographs had been disseminated by Kenneth Heslep, Hill’s ex-husband (also named as a defendant). Hill also sued talk-radio host Joe Messina for statements referencing the images that he made on-air and in an article posted to his blog, as well as Salem Media Group, Inc. (owner of the conservative political blog RedState) and RedState editor Jennifer Van Laar for their alleged roles in the distribution of the nude photos. Hill alleged that the actions of each defendant violated California Civil Code § 1708.85, the state’s revenge porn law, which prohibits the “distribution” of certain types of intimate photographs (among other types of media) without the consent of the depicted individual. Distribution is not defined by the statute, but Judge Yolanda Orozco of the Los Angeles County Superior Court construed it broadly enough to include activities such as dissemination of prohibited photographs by an individual to others as well as publication by media outlets. On April 7, 2021, Judge Orozco heard and granted Mail Media’s anti-SLAPP motion to strike; Hill has filed a notice of appeal.

Prong 1: In analyzing prong one, Judge Orozco noted that “reporting the news is speech subject to the protections of the First Amendment and subject to an anti-SLAPP motion if the report concerns a public issue or an issue of public interest,”[5] and “‘[t]he character and qualifications of a candidate for public office constitutes a “public issue or public interest”’ for purposes of section 425.16.”[6] While the court agreed with Hill that “the gravamen of her Complaint against [Mail Media] is [its] distribution of Plaintiff’s intimate images,”[7] it noted that this distribution occurred via an online news publication, and the “intimate images published by Defendant spoke to Plaintiff’s character and qualifications for her position, as they allegedly depicted Plaintiff with a campaign staffer whom she was alleged to have had a sexual affair with and appeared to show Plaintiff using a then-illegal drug…”[8] Thus, “the gravamen of Plaintiff’s Complaint against Defendant constitutes protected activity under Section 425.16(e)(3) and (4).”[9]

Prong 2: On the second (merits) prong, Judge Orozco noted that Hill’s claims presented a novel intersection of California’s anti-SLAPP and revenge porn laws. Section 1708.85(a) states, in relevant part,

A private cause of action lies against a person who intentionally distributes… a photograph… of another, without the other’s consent, if (1) the person knew that the other person had a reasonable expectation that the material would remain private, (2) the distributed material exposes an intimate body part of the other person… and (3) the other person suffers general or special damages…

However, Judge Orozco held that the newspaper’s activities fell squarely within the “matter of public concern” exemption contained in § 1708.85(c)(4), as the published images “speak to Plaintiff’s character and qualifications for her position as a Congresswoman.”[10] Thus, “Plaintiff failed to carry her burden establishing that there is a probability of success on the merits of her claim.”[11]

Other Case Notes & Attorneys’ Fees Awards: In a subsequent hearing on June 2, 2021, Judge Orozco granted Mail Media’s motion for costs and prevailing-party attorneys’ fees, totaling $104,747.75.[12] The dismissal of Mail Media’s claims followed the earlier dismissals and awards of attorneys’ fees for all of the other defendants except for Heslep, the lone defendant remaining in the case.[13] In total, Hill has been ordered to pay over $200,000 in attorneys’ fees to the prevailing defendants.[14]

Of note, Hill was ordered to pay $30,000 in fees and costs to Messina, the radio personality who merely commented about the pictures on his program and blog.[15] Shortly after Messina filed his anti-SLAPP motion to strike, but before the scheduled hearing, Hill voluntarily withdrew her claims against Messina. Despite this, Judge Orozco entertained Messina’s motion for attorneys’ fees as the prevailing defendant under Section 425.16. Judge Orozco noted that “‘because a defendant who has been sued in violation of his… free speech rights is entitled to an award of attorney fees, the trial court must, upon defendant’s motion for a fee award, rule on the merits of the SLAPP motion even if the matter has been dismissed prior to the hearing on that motion.’”[16] Judge Orozco concluded that Messina was the prevailing party on the merits of the motion to strike and granted the motion for attorneys’ fees.

While the trial court’s orders are non-precedential, the Court of Appeal will have a chance to review them, as on June 18, 2021, Hill filed notices of appeal for the orders granting the anti-SLAPP motions of Mail Media, Van Laar, and Salem Media.

2. Muddy Waters, LLC v. Superior Court, 62 Cal. App. 5th 905 (2021)

Facts: In 2017, Perfectus Aluminum, Inc., a distributor of aluminum products, sued Muddy Waters, LLC, a financial analysis firm that engages in activist short selling, following the latter’s publication of a pair of reports that allegedly implicated Perfectus in a scheme to inflate aluminum sales for Zhongwang Holdings, Ltd., a publicly traded Chinese company.[17] The two reports (“Dupré Reports”) were published by Muddy Waters on a publicly accessible website under the business pseudonym “Dupré Analytics.” In its complaint, Perfectus alleged that U.S. Customs detained a shipment of the company’s aluminum awaiting export in the port of Long Beach and lost potential business as a result of the allegations in the Dupré Reports, bringing claims for 1) violation of California’s Unfair Competition Law; 2) trade libel; and 3) intentional interference with prospective economic advantage.

The Superior Court of San Bernardino County denied Muddy Waters’s anti-SLAPP motion on the grounds that Muddy Waters failed to prove that the causes of action arose from protected activity and, alternatively, that the commercial speech exemption of Section 425.17(c) applied to the publication of the Dupré Reports, thereby barring an anti-SLAPP challenge. Because the trial court found Section 425.17 applied, Muddy Waters lacked the immediate right of appeal that is otherwise available upon denial of an anti-SLAPP motion and thus sought a writ of mandate from the Court of Appeal.

Prong 1: The Court of Appeal began its analysis of the first prong by highlighting the third category of protected activities in § 425.16(e): “any written or oral statement or writing made in a place open to the public or a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest.” The Court divided the first prong’s analysis into two stages. In the first stage, the Court determined whether a publicly accessible website constitutes a public forum, and found that it does, as “Internet postings on websites that ‘are open and free to anyone who wants to read the messages’ and ‘accessible free of charge to any member of the public’ satisfies the public forum requirement of section 425.16.”[18]

In the second stage, the Court asked whether the content of the Dupré Reports represented an issue of public interest, and found that it did because the reports alleged that Zhongwang was artificially inflating reported sales and allegations of “mismanagement or investor scams” made against a publicly traded company constitute an “issue of public interest” for purposes of the anti-SLAPP law.[19]

Commercial Speech Exemption: Before moving to the merits prong of the anti-SLAPP analysis, the Court of Appeal addressed the trial court’s determination that the § 425.17(c) commercial speech exemption applied, thereby barring Muddy Waters’s ability to bring an anti-SLAPP motion. The Court noted that the plaintiff has the burden of proof to establish the applicability of the commercial speech exemption, and that the exemption is “narrow,” excluding only a “‘subset of commercial speech—specifically, comparative advertising.’”[20] Thus, it noted, the commercial speech exemption is triggered only with respect to “speech or conduct by a person engaged in the business of selling or leasing goods or services when… that challenged [speech or] conduct pertains to the business of the speaker or his or her competitors.”[21] In other words, the Court noted, the commercial speech exemption does not apply in circumstances like the current case, where a defendant has made representations of fact about a noncompetitor’s goods in order to promote sales of the defendant’s goods or services. Accordingly, the Court of Appeal reversed the Superior Court’s determination that the commercial speech exemption applied and barred Muddy Waters from bringing an anti-SLAPP motion.

Prong 2: The Court of Appeal next determined whether Perfectus had satisfied the merits prong for each of its three causes of action.

For the California UCL claim, the Court wrote that “nothing in the record suggests that plaintiff has lost money or property such that it would have standing to pursue a UCL action against Muddy Waters.”[22] The Court found that Perfectus had not produced any evidence that would establish a nexus between the alleged unfair practice (publication of the Dupré Reports) and the loss of property (the aluminum that was detained by U.S. Customs), and therefore lacked standing to bring a UCL claim.

For the trade libel claim, the Court noted that Perfectus failed to produce evidence identifying a specific third party that was deterred from conducting business with Perfectus as a result of the Dupré Reports, a required element for the claim. It wrote, “‘it is not enough to show a general decline in [Perfectus’s] business resulting from the falsehood, even where no other cause for it is apparent… it is only the loss of specific sales [as a result of the defendant’s actions] that can be recovered.’”[23] Thus, Perfectus’s failure to specify a particular business partner that was convinced by the Dupré Reports to refrain from dealing with Perfectus doomed the trade libel cause of action.

Finally, on the intentional-interference-with-prospective-economic-advantage claim, the Court noted that Perfectus would need to prove an “actual economic relationship with a third party”[24] and that the relationship “‘contains the probability of future economic benefit to [Perfectus],’”[25] but that Perfectus failed to submit evidence that identified such an actual economic relationship with a specific third party.[26]

Result: The Court of Appeal issued a writ of mandate directing the Superior Court to vacate its order denying Muddy Waters’s anti-SLAPP motion and to enter in its place a new order granting the motion. Perfectus has sought review in the California Supreme Court.

3. Verceles v. Los Angeles Unified School District, 63 Cal. App. 5th 776 (2021)

Facts: Plaintiff Junnie Verceles, a Filipino man who was 46 years old at the time he filed his complaint in March 2019, was a teacher in the Los Angeles Unified School District from 1998 until his termination on March 13, 2018.[27] On December 1, 2015, following unspecified allegations of misconduct, Verceles was reassigned and placed on paid suspension, which Verceles described as “teacher jail.” In November 2016, Verceles filed a discrimination complaint with the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing (DFEH) while an investigation by the District into the alleged misconduct was still underway. The DFEH case was closed on March 7, 2017, and roughly one year later, the District terminated Verceles’s employment. Verceles alleged three violations of California’s Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA): 1) age discrimination, 2) race and national origin discrimination, and 3) retaliation; in response, the District filed an anti-SLAPP motion to strike each of the three causes of action. After the Los Angeles County Superior Court granted the District’s motion, Verceles appealed; the Court of Appeal reversed.

Prong 1: The District argued that each cause of action arose out of its investigation into teacher misconduct, and was thus protected activity under § 425.16(e). Verceles argued that the gravamen of his complaint was not the investigation into teacher misconduct, but the discrimination and retaliation that resulted in his firing by the District. The trial court granted the motion, characterizing the investigation and resulting termination (and alleged discrimination and retaliation) as a single “proceeding” that gave rise to the causes of action.

The Court of Appeal, however, rejected the District’s attempt to “define the alleged adverse action broadly to encompass the entirety of its investigation into Verceles’s purported misconduct.”[28] Instead, the Court found persuasive Verceles’s argument that the investigation as a whole into his alleged misconduct was not tainted by discriminatory or retaliatory intent. After all, Verceles argued, the investigation began before Verceles filed his DFEH complaint, and so up to that point, there was nothing for the District to retaliate against. Furthermore, Verceles argued, the District’s other investigations into alleged misconduct did not demonstrate a pattern of discrimination against protected groups that resulted in the requisite disparate impact; however, according to Verceles, the District’s termination practices and use of “teacher’s jail” to discipline a relative few number of teachers like him did demonstrate such a pattern of disparate, adverse impacts on protected groups. Thus, the Court concluded that the activities that underpinned Verceles’s complaint were his reassignment to “teacher’s jail” and termination.

The District argued that the “investigation was an ‘official proceeding authorized by law’ for purposes of [425.16(e)(2)],” and that all actions taken in the course of the investigation—including the decision to reassign and terminate Verceles—fell within the ambit of this protected activity.[29] The Court acknowledged that the District was generally correct to state that an investigation into alleged misconduct by a public employee is categorized as “an official proceeding”; however, the Court rejected the idea that every action taken during the course of such an investigation constituted a protected activity for anti-SLAPP purposes.[30] “Such an interpretation,” wrote the Court, “ignores the plain language of the statute, which requires a claim be based on a written or oral statement made in connection with the proceeding.”[31] Instead, Section 425.16(e) protects the District’s speech and petitioning activity “that led up to or contributed” to the decision to reassign and terminate Verceles, but it did not protect the actual acts of reassignment and termination.[32] Thus, “In the absence of any oral or written statements from which Verceles’ claims arise, the District’s decisions to place Verceles on leave and terminate his employment are not protected activity within the meaning of [Section 425.16(e)(2)].”[33]

Result: Thus, the Court held that the District failed to meet its burden under the first prong of the anti-SLAPP analysis and reversed the trial court’s judgment granting the District’s motion to strike and motion for attorney’s fees as the prevailing party. The Court also granted Verceles’s the costs related to his appeal of the order granting the motion to strike. The District filed a petition for review, which is currently pending before the California Supreme Court.

4. Appel v. Wolf, 839 F. App’x 78 (9th Cir. 2020)

Facts: Defendant Robert Wolf is an attorney who represents Concierge Auctions, LLC, a company that specializes in auctioning off luxury real estate. A dispute arose between Concierge and the plaintiff Howard Appel over the sale of property in Fiji. During the course of this dispute, Wolf sent an email containing an allegedly defamatory statement that Wolf knew Appel and that Appel “had legal issues (securities fraud).”[34] After Appel sued Wolf for defamation, Wolf filed an anti-SLAPP motion to strike, arguing that the statements in the email were made pursuant to settlement discussions in the course of litigation and so were protected under Section 425.16. The district court denied the motion to strike and Wolf appealed. Though it found the district court erred in its prong-one analysis, the Ninth Circuit found such error harmless and therefore affirmed.

Prong 1: In its first prong analysis, the Ninth Circuit held that the district court erred in holding that Wolf’s email communication was not protected activity, as acts that occur in the course of litigation “are generally considered protected conduct falling within section 425.16(e)(2)’s broad ambit.”[35] The panel noted that “[t]his protection extends to ‘an attorney’s communication with opposing counsel on behalf of a client regarding pending litigation’ and includes ‘an offer of settlement to counsel.’”[36] The panel then found that “[t]he district court misapplied California law when it reasoned that Wolf’s email—which was sent to Appel’s counsel, allegedly ‘begging for a phone[-]call discussion about possible settlement of Appel’s case against Concierge’—was insufficiently concrete to qualify as protected conduct,” because “Section 425.16(e)(2) has no such ‘concreteness’ requirement.”[37] Thus, the allegedly libelous email qualified for Section 425.16(e)(2)’s protection, and Wolf satisfied his burden of establishing the first prong.

Prong 2: However, the Ninth Circuit held that the district court’s error on prong one was ultimately harmless, because Appel was “reasonably likely to succeed on the merits of his claim, given that Wolf’s email was facially defamatory and not immunized by California’s litigation privilege.”[38] First, the complaint’s allegations and the email itself supported the district court’s finding that Wolf’s statement “would have negative, injurious ramifications on [Appel’s] integrity.”[39] Next, though Wolf’s statement was made in the context of settlement negotiations, the panel held it was not privileged, as “the privilege ‘does not prop the barn door wide open’ for every defamatory ‘charge or innuendo,’ merely because the libelous statement is included in a presumptively privileged communication,”[40] and “Appel established that Wolf’s false insinuation that he had been involved in securities fraud is not reasonably relevant to Appel’s underlying dispute with Concierge.”[41]

Result: The Ninth Circuit thus affirmed the district court’s denial of Wolf’s anti-SLAPP motion.

5. SB 329 Proposes Limitation on Use of Anti-SLAPP Motions in “No Contest” Wills and Trust Actions

Finally, a new bill, California Senate Bill 329, introduced by Senator Brian Jones (R, 38th Dist.), proposes to prohibit the use of anti-SLAPP motions in actions relating to wills and trusts. The bill would amend Section 425.17 to add the following provision: “(e) Section 425.16 does not apply to an action to enforce a no contest clause contained in a will, trust, or other instrument. As used in this subdivision, ‘no contest clause’ has the meaning provided in Section 21310 of the Probate Code.” A “no-contest” clause is a provision that disinherits a beneficiary who challenges a will or trust.

The Senate Floor Analysis of the bill notes that “[a]lthough commonly associated with the protection of constitutional rights, the anti-SLAPP statute applies to a broad range of contexts, including proceedings to enforce a no-contest clause in a trust or will that penalizes beneficiaries who challenge the terms of the will without probable cause.” The Senate Judiciary notes that two recent Court of Appeal cases “establish that the anti-SLAPP statute applies to no-contest enforcement petitions.”[42] SB 329 is sponsored by the California Conference of Bar Associations and the Executive Committee of the Trusts and Estates Section of the California Lawyers Association, which “argue that the statute was not intended to apply in this context and that it offers minimal upside while opening the door to needless litigation and cost.”

- [1] Cal. Civ. Code § 425.16(b)(1).

- [2] Id.

- [3] Id. § 425.16(c)(1).

- [4] Hill v. Heslep et al., Case No. 20STCV48797, at *1 (Apr. 7, 2021, L.A. Cnty. Super. Ct.).

- [5] Id. at *8 (citing Liberman v. KCOP Television, Inc., 110 Cal. App. 4th 156, 164 (2003)).

- [6] Id. at *6-7 (quoting Collier v. Harris, 240 Cal. App. 4th 41, 52 (2015)).

- [7] Id. at *7-8.

- [8] Id. at *8.

- [9] Id. at *7.

- [10] Id. at *13.

- [11] Id.

- [12] Hill v. Heslep et al., Case No. 20STCV48797 at *5 (Super. Ct. of L.A. Cnty., June 2, 2021).

- [13] Nathan Solis, Katie Hill Owes Daily Mail $105K for Attorney Fees in Nude Photo Fight, Courthouse News Service (June 2, 2021),

https://www.courthousenews.com/katie-hill-owes-daily-mail-105k-for-attorney-fees-in-nude-photo-fight/. - [14] Id.

- [15] Hill v. Heslep, et. al., Case No. 20STCV48797, at *12 (Super. Ct. of L.A. Cnty., May 4, 2021).

- [16] Id. at *3 (citing Pfeiffer Venice Properties v. Bernard, 101 Cal. App. 4th 211, 218 (2002)).

- [17] Muddy Waters, LLC v. Superior Ct., 62 Cal. App. 5th 905, 912-93 (2021), reh’g denied (Apr. 23, 2021), petition for review filed (May 18, 2021).

- [18] Muddy Waters, 62 Cal. App. 5th at 917 (citing ComputerXpress, Inc. v. Jackson, 93 Cal. App. 4th 993, 1007 (2001)).

- [19] Id. at 918.

- [20] Id. at 919-20 (citing Dean v. Friends of Pine Meadow, 21 Cal. App. 5th 91, 105 (2018)).

- [21] Id. at 919.

- [22] Id. at 923.

- [23] Id. at 925 (citing Erlich v. Etner, 224 Cal. App. 2d 69, 73 (1964)).

- [24] Id. at 926.

- [25] Id. (citing Korea Supply Co. v. Lockheed Martin Corp., 29 Cal 4th 1134, 1164 (2003)).

- [26] Muddy Waters, 62 Cal. App. 5th at 926-27.

- [27] Verceles v. Los Angeles Unified Sch. Dist., 63 Cal. App. 5th 776, 779 (2021), petition for review filed (June 3, 2021).

- [28] Id. at 785.

- [29] Id. at 787.

- [30] Id.

- [31] Id.

- [32] Id.

- [33] Id. at 788.

- [34] Appel v. Wolf, 839 F. App’x 78, 80 (9th Cir. 2020).

- [35] Id.

- [36] Id. (citing GeneThera, Inc. v. Troy & Gould Pro. Corp., 171 Cal. App. 4th 901, 905 (2009)).

- [37] Id. at 80.

- [38] Id.

- [39] Id.

- [40] Id. at 81 (quoting Nguyen v. Proton Technology Corp., 69 Cal. App. 4th 140, 150 (1999)).

- [41] Id.

- [42] Citing Key v. Tyler, 34 Cal. App. 5th 505 (2019); Urick v. Urick, 15 Cal. App. 5th 1182 (2017).

California Anti-SLAPP Motions Are Safe in Federal Courts . . . For Now

For over two decades, the Ninth Circuit has treated California’s anti-SLAPP statute as substantive law and refrained from applying the Erie doctrine to question whether anti-SLAPP motions generally should be precluded in federal courts absent a “direct conflict.”1 2 Anti-SLAPP motions are often favored by defendants in California, as they can provide speedy relief for individuals or entities sued for conduct involving their rights of free speech or petition to potentially obtain an early exit from litigation before significant costs accrue, by creating a procedural mechanism whereby defendants can require plaintiffs alleging such claims to substantiate their merits at the case’s earliest stages.3

In recent years, however, federal courts across at least five circuits have called this deferential approach into question when evaluating their own respective states’ versions of similar statutes. Rather than holistically defer to state anti-SLAPP laws as substantive absent a “direct conflict,” courts in the Second, Fifth, Tenth, and Eleventh Circuits, along with the D.C. Circuit, have consistently invoked the Erie doctrine to evaluate whether each anti-SLAPP provision is substantive or procedural.4

In August 2022, the Ninth Circuit spoke up to reaffirm its position regarding the propriety of anti-SLAPP motions in federal courts within its jurisdiction. Recognizing the deepening divide ripping across the country, the Court in CoreCivic v. Candide Group again protected California’s anti-SLAPP statute from the Erie inquiry, holding that no basis existed to undermine its previous position that no conflict justifies precluding the motions in Ninth Circuit federal courts.5 6

While acknowledging the existence of out-of-circuit decisions holding otherwise with respect to other states’ anti-SLAPP statutes, these sister circuit decisions left the Ninth Circuit unfazed with its approach to California’s statute.7 Furthermore, the Court quelled minority opinions within the Ninth Circuit that suggested California’s anti-SLAPP statutes are trumped by the Federal Rules of Procedure Rule 12(b)(6) and Rule 56, governing motions to dismiss and motions for summary judgment, respectively.8 Rather, the Court reconciled any potential conflicts by explaining that anti-SLAPP statute provisions “must be analyzed under the same standard” that Rules 12(b)(6) and 56 impose, again treating the anti-SLAPP provisions as purely substantive.9

CoreCivic may cause a ripple effect across other circuits and deepen the stark divide. The issue is ripe for the Supreme Court to break its longstanding silence on whether and to what extent state anti-SLAPP laws are preempted.10 While the silence has sparked creative potential alternatives, such as the Uniform Public Expression Protection Act (UPEPA), a model anti-SLAPP statute approved by the Uniform Law Commission in 2020, states have been slow to adopt it, leaving litigants in other jurisdictions open to the possibility of forum shopping in circuits that view state anti-SLAPP statutes as conflicting with federal law.11 Litigants in the Ninth Circuit, however, need not worry about such things—at least not yet.

- 1 See, e.g., U.S. ex rel. Newsham v. Lockheed Missiles & Space Co., 190 F.3d 963, 972 (9th Cir. 1999) (hereinafter “Newsham”) (internal citations omitted) (In the absence of a “direct collision” between a state anti-SLAPP law and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, state statute applies in federal diversity actions.).

- 2 It is well-established that when state law conflicts with federal law, courts use the Erie test to determine which law applies. The first step to the Erie test is whether “a Federal Rule of Civil Procedure ‘answer[s] the same question’ as the [special motion to strike].” Abbas v. Foreign Pol’y Grp., LLC, 783 F.3d 1328, 1335 (D.C. Cir. 2015) (quoting Shady Grove Orthopedic Assocs., P.A. v. Allstate Ins. Co., 559 U.S. 393, 398-99 (2010)). If the result is in the affirmative, then the Federal Rule governs. Id. Although an exception arises if the Federal Rule violates the Rules Enabling Act, the U.S. Supreme court has “rejected every challenge to the Federal Rules that it has considered under the Rules Enabling Act.” Id. at 1336.

- 3 Cal. Code of Civ. Proc. § 426.16.

- 4 See La Liberte v. Reid, 966 F.3d 79, 86–88 (2d Cir. 2020); Klocke v. Watson, 936 F.3d 240, 244–49 (5th Cir. 2019); Los Lobos Renewable Power, LLC v. AmeriCulture, Inc., 885 F.3d 659, 668–73 (10th Cir. 2018); Carbone v. Cable News Network, Inc., 910 F.3d 1345, 1349–57 (11th Cir. 2018); Abbas v. Foreign Pol’y Grp., LLC, 783 F.3d 1328, 1333–37 (D.C. Cir. 2015).

- 5 CoreCivic v. Candide Grp., No. 20-17285, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 24417, at *10-12 (9th Cir. Aug. 30, 2022), reh’g denied en banc, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 29257 (9th Cir. Oct. 20, 2022).

- 6 Greenberg Traurig, LLP has represented and continues to represent CoreCivic in a wide array of matters, but did not participate in the Candide litigation.

- 7 CoreCivic, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 24417, at *15.

- 8 Id. at *16.

- 9 Id.

- 10 The Supreme Court has consistently refused to take cases involving state anti-SLAPP laws. See, e.g., Yagman v. Edmondson, 723 Fed. App’x 463 (9th Cir. 2018), cert. denied, 139 S. Ct. 823 (2019); Planned Parenthood Fed’n of Am., Inc. v. Ctr. for Med. Progress, 897 F.3d 1224 (9th Cir. 2018), cert denied, 139 S. Ct. 1446 (2019). As recently as February 2021, the Supreme Court again refused by denying review in Clifford v. Trump, 141 S.Ct. 1374 (2021), which presented the conflict between the Ninth Circuit and the Fifth Circuit’s holdings on the applicability of the Texas anti-SLAPP law in federal court.

- 11 Only three states have enacted UPEPA (Hawaii, Kentucky, and Washington), and five states have introduced it (Indiana, Iowa, Missouri, New Jersey, and North Carolina) as of November 2022. See Public Expression Protection Act, Uniform Law Commission (Nov. 1, 2022).

SLAPP Cases Decided by the California Supreme Court

SLAPP Cases Decided by the California Supreme Court

The following are opinions issued by the California Supreme Court concerning the anti-SLAPP statute (CCP § 425.16). Clicking on the name of the case will lead to the text of the opinion. For opinions issued in and after 2014, clicking on the case name will lead to the text of the opinion on Google Scholar.

Baral v. Schnitt

California Supreme Court, 2016

1 Cal.5th 376, 205 Cal.Rptr.3d 475, 376 P.3d 604

Plaintiff’s second amended complaint contained causes of action for breach of fiduciary duty, constructive fraud, negligent misrepresentation, and a claim for declaratory relief. Defendant’s anti-SLAPP motion sought to strike all references to an audit by an accounting firm. The trial court denied the motion without deciding whether the complaint contained allegations of protected activity, ruling that the anti-SLAPP motion applied only to entire causes of action as pleaded in the complaint, or to the complaint as a whole, not to isolated allegations within causes of action. The Supreme Court reversed, holding that, as used in § 425.16(b)(1), “cause of action” referred to allegations of protected activity asserted as grounds for relief, and thus the anti-SLAPP statute could reach distinct claims within pleaded counts, requiring a probability of prevailing on any claim for relief based on allegations of protected activity, even if mixed with assertions of unprotected activity. The Court disapproved of the opinion in Mann v. Quality Old Time Service, Inc. (2004) 120 Cal.App.4th 90.

Barrett v. Rosenthal

California Supreme Court, 2006

40 Cal.4th 33, 51 Cal.Rptr.3d 55, 146 P.3d 510

Three plaintiffs, vocal critics of alternative medicine, sued our client, breast-implant awareness activist Ilena Rosenthal, for defamation and related claims, based on critical comments she made about two of them on the Internet. The trial court granted her anti-SLAPP motion. The Court of Appeal affirmed this ruling as to two plaintiffs, but reversed as to the third. The California Supreme Court held that the third plaintiff’s claims should be dismissed as well, ruling that Rosenthal was protected from civil liability for republication of the words of another on the Internet by section 230 of the federal Communications Decency Act. On remand, the trial court awarded more than $434,000 for attorneys fees.

Barry v. The State Bar of California

California Supreme Court, Jan. 5, 2017

2 Cal.5th 318, 212 Cal.Rptr.3d 124, 386 P.3d 788

Plaintiff attorney filed an action seeking to vacate a stipulation she had entered into to having committed professional misconduct and a 60-day suspension from the practice of law. The trial court granted the State Bar’s anti-SLAPP motion, ruling that the claims arose from protected activity and that plaintiff could not establish a probability of prevailing, because (inter alia) a superior court lacked subject mater jurisdiction over attorney discipline matters. The trial court also awarded $2,575 in attorneys’ fees. Plaintiff appealed the fee award. The Court of Appeal reversed the fee award, finding that the trial court’s lack of subject matter jurisdiction precluded it from ruling on the State Bar’s anti-SLAPP motion and awarding fees. The Supreme Court reversed the Court of Appeal and upheld the fee award, holding that the superior court properly found that plaintiff had failed to show a probability of prevailing on her claim because the superior court lacked subject matter jurisdiction, and that said ruling was not on the merits of plaintiff’s claim.

Bonni v. St. Joseph Health System

California Supreme Court, 2021

11 Cal.5th 995, 281 Cal.Rptr. 3d 678, 491 P.3d 1058

Briggs v. ECHO

California Supreme Court, 1999

19 Cal.4th 1106, 81 Cal.Rptr.2d 471, 969 P.2d 564