Child’s Best Interest in Custody Cases

What is the Best Interests of the Child Checklist?

The Best Interests of the Child is a standard that the courts use to determine what’s best for the kids when parents are disputing issues such as custody, access, support, special expenses, etc. Rarely do parents go to court over disputes, but when they do, the judge will look at family relationships, primary caretaking responsibilities, cultural and religious relationships, special needs, and such to make his or her ruling.

The Pain of Family Court………

Determining the Best Interest of a Child

Generally, the factors a judge will consider when determining the best interest of a child include the following main reasons:

- Child’s age: Young children generally need more hands-on care. Courts look at the bond between child and parent when evaluating child custody options. In addition, when children are young, judges frequently defer to the parent who has been the primary caregiver in the child’s life. Some courts also will consider the child’s wishes, depending on their age.

- Consistency: Courts generally prefer to keep kids’ routines consistent. This includes living arrangements, school or child care routines, and access to extended family members. Family court judges prefer not to disrupt a child’s routine when possible.

- Evidence of parenting ability: Courts look for evidence that the parent requesting custody is genuinely able to meet the child’s physical and emotional needs, including food, shelter, clothing, medical care, education, emotional support, and parental guidance. Courts also consider the parents’ physical and mental health.

- Impact of changing the existing routine: When considering a change, the courts also try to determine how that change would affect the child. Generally, judges try to limit changes that would have a negative impact.

- Safety: This factor is always top of mind in family court, and judges will readily deny custody in cases where they believe the child’s safety would be compromised.

What to Show the Court

You can show the judge that you have your child’s best interests at heart by showing that you have been actively involved in his or her life and have provided attentive and loving care.

You can demonstrate this by showing that you have enrolled your child in school, are involved in their education and upbringing, have participated in extracurricular activities, and have made other parenting decisions demonstrating an interest in nurturing your child.

In cases where both parents are involved, the judge may also consider whether one parent is more willing to foster a loving relationship with the other parent, so working to rebuild trust with your ex also can help to demonstrate your intentions.

Factors Against a Child’s Best Interests

Judges strongly favor keeping a child in an arrangement that the child is familiar with, such as allowing a child to remain in the same school or neighborhood. To that end, judges generally do not favor an arrangement in which one parent is denied access to the child or where visitation would be difficult.

Even in cases where one parent is granted sole physical custody, the other parent usually has the right to visitation. This is because child custody laws in most states favor custody arrangements that allow both parents to maintain a close and loving relationship with their child.2

When Is Relocating Considered Best?

Relocating may or may not be in your child’s best interest. For example, the judge will typically deny a request to move if he or she believes the parent making the request is trying to deny or limit the other parent’s access.

However, moving may be in the best interest if the move allows a child to attend a better school, provides access to child care or a support system, or would benefit the child in some other way that can be demonstrated in court.

Finally, remember that the court is looking at your child holistically. They don’t just consider whether you’re a fit parent. When determining custody, they also aim to keep all other aspects of the child’s life consistent while ensuring that both parents have the opportunity to be an active part of the child’s life.

We also have the GrandParents Rights To Visit Family Law Packet including the FL-375 Form Needed to File

Focusing on the “Best Interests” of the Child

Parents may resolve a child custody matter out-of-court through negotiation and agreement. If they can’t, a court will have to decide the issue. But either way, finding the solution that’s in the child’s “best interests” should be paramount. But what does “the child’s best interest” mean? It may seem straightforward, but the term has a particular meaning in family law. Read on to learn more about the best interests of the child standard. The article will explain the doctrine and the factors courts use when applying it.

The Child’s Best Interests in Custody Cases

Custody and visitation decisions should center on the child’s “best interests.” That means making the child’s growth into young adulthood the top priority. Parents and courts should consider factors such as the child’s:

- Happiness

- Security

- Mental health

- Emotional development

Generally, the child should have a close and loving relationship with both parents. But promoting such relationships is difficult in an emotional and contentious dispute.

You must focus on making decisions in your child’s best interest. The choices you or a court make now will affect your child’s development. They will also impact your relationship with your child in many crucial ways for years to come.

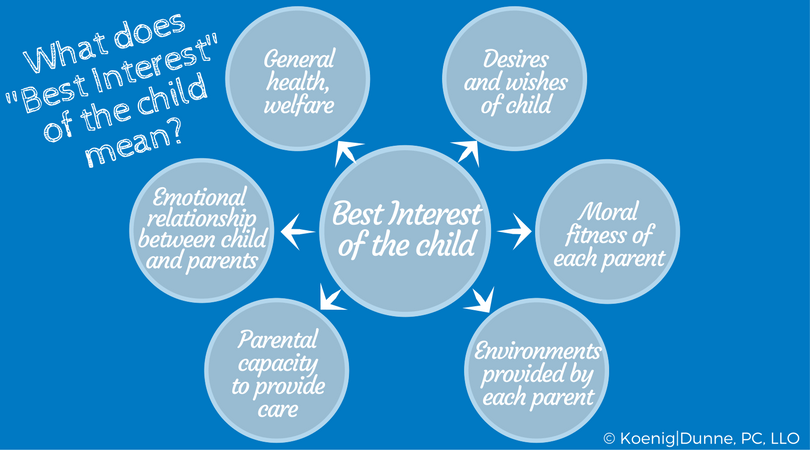

What Factors Determine the Child’s Best Interests?

But what, exactly, is the child’s best interest standard? It isn’t easy to define. The different sides in a custody dispute often have different perspectives. That can lead to an honest disagreement over what’s best for the child. The good news is that there are some common factors we can use in most custody situations, such as the following:

- The child’s wishes (whether a state considers the child’s wishes and at what age varies by state)

- The mental and physical health of the parents

- Any special needs a child may have and how each parent takes care of those needs

- Religious or cultural considerations

- The need for continuing a stable home environment

- Other children whose custody is relevant to this child’s custody arrangement

- The child’s opportunity to interact with their extended family, such as grandparents

- Interactions and interrelationships with other members of the household

- Adjustments to school and community

- The age and sex of the child

- Whether there is a pattern of domestic violence in the home

- Parental use of excessive discipline or emotional abuse

- Evidence of parental drug, alcohol, or child/sex abuse

How Courts Use the Factors

Courts don’t look at one factor when making a best-interest decision. It will instead consider all the factors related to the child’s circumstances. The court will also consider the parent or caregiver’s capacity to parent. Ultimately, the court’s paramount concern is the child’s safety and happiness.

We also have the GrandParents Rights To Visit Family Law Packet including the FL-375 Form Needed to File

Child Custody Best Interest Factors

There are several factors that the judge will typically look into during best interest determinations. In modern family court, these factors are usually significant concerns for both parents.

Some of the things they will look at include any incidence of neglect, alcohol or drug use, emotional abuse, physical violence, or sexual abuse. It will also look at whether the parent actively committed such acts against the child, the other parent, or another party.

Once they hear concerns about the abuse and safety of the child, they will also review evidence and testimony on who was responsible for ensuring the needs of the child were met. Some of the things they will be looking at include:

- Getting the child ready for school in the mornings

- Taking the child to school

- Picking the child up from school

- Helping the child with homework

- Making meals for the child

- Caring for the child when they are at home

- Arranging for playdates

- Bathing and getting the child ready for bed

- Putting the child to bed

- Making medical appointments for the child

- Taking the child for their medical appointments

- Attending teacher-parent conferences

- Ensuring the child takes part in extracurricular activities

- Taking care of the child when they are sick

- The parent’s work schedule

- The special needs of the child

- Whether any of the parents intend to move out of the area

- Issues with alcoholism or drugs

- Which party is more willing to work with the other parent in the interest of the child

- Particular concerns about the child’s safety with family members and a parent

- If the responsibilities or duties recently changed and the reasons for that.

We also have the GrandParents Rights To Visit Family Law Packet including the FL-375 Form Needed to File

Best Interest Factors When Deciding Custody

Each state has its own set of factors—typically referred to as the best interest factors—that judges must evaluate when deciding custody. Although states may differ slightly, the most common factors include:

- the love, affection, and emotional ties between each parent and the child

- each parent’s ability to provide the child with a home, food, clothing, and the necessities of life

- the child’s preference (this factor is restricted in some states and greatly depends on the child’s age, mental capacity, and willingness to provide an opinion)

- each parent’s ability to give the child loving support, parental guidance, and discipline

- stability and consistency (courts like to keep the child’s routine consistent, so if the child has routinely lived with one parent and has developed a schedule, school, and childcare routines, the court is less likely to disrupt the child’s life with a change in custody)

- each parent’s moral fitness, drug and alcohol history, and the mental and physical health

- whether either parent has a history of child or domestic abuse

- each parent’s willingness to facilitate a healthy and continuing relationship between the child and the child’s other parent

- the child’s age and any special needs (younger children may require nursing and special needs children require specialized care that not all parents are capable of providing)

- the history of the child’s relationship with each parent. For example, has the child’s mother been a stay-at-home parent and bonded with the child to the extent that awarding substantial or sole custody to the child’s other parent would be detrimental?

- the child’s home, school, and community record, and

- the child’s relationships with other family members in the home, such as stepparents and siblings.

It’s important to understand that no single factor is more important than the other. Instead, the court will look at all the factors, facts, and family history to decide whether one or both parents are best suited to care for the child on a day-to-day basis. Additionally, each court can evaluate any other factors that the judge believes will affect the child’s best interests.

Some Courts Ask for Help

Some states allow the judge to ask a division of the family court for assistance with evaluating what’s in a child’s best interest when it comes to deciding custody.

For example, in Michigan, parents with custody disputes must file a motion with the Friend of the Court, which begins the process of a custody investigation. During the investigation, a social worker specially trained in custody and parenting time will meet separately with each parent and the child to evaluate what’s in the child’s best interest for custody and parenting time. At the end of the investigation, the social worker will prepare a written recommendation detailing the findings of the interviews (listing findings for each best interest factor) and will submit it to the court. In most cases, the judge adopts the worker’s recommendations, even if one parent objects.

Other states require parents to attend court-ordered mediation before asking the judge to decide. Mediation is a process where a neutral third-party helps facilitate a discussion between the parents about custody and helps the parents reach an agreement instead of asking the court to do it for them.

Custody mediators are trained in their state’s best interest factors and will help the parents understand how a judge would decide custody based on those factors, which avoids costly and needless litigation in court.

Although you may think you know what’s in your child’s best interest, it may not line up with your child’s other parent or what the court determines. Consider hiring an experienced family law attorney before you file for custody or try to resolve a custody dispute on your own. cited

We also have the GrandParents Rights To Visit Family Law Packet including the FL-375 Form Needed to File

The Best Interests of the Child: Factors Judges Consider in Deciding Custody

Learn what judges look for when they’re deciding which parenting arrangements would be in the children’s best interests.

Each Parent’s Ability to Meet Children’s Needs

The most basic part of the “best interests” standard is that custody decisions should serve the children’s health, safety, and welfare. Judges will look at whether one or both parents are able to handle a child’s special educational, medical, mental health, and other needs.

Children’s Relationship With Both Parents

Many states have an explicit policy of encouraging frequent and continuing contact between children and their divorced or separated parents. In pursuit of that goal, judges will consider several factors related to the past and present parent-child relationships.

Parents’ Willingness to Support Each Other’s Relationship With Their Children

Judges will look at the parents’ history of cooperating—or not— with each other around their parenting schedule. For instance, judges might want to know things like whether one parent interferes with visitation in any way.

Judges will also look for evidence of each parents’ willingness to foster a good relationship between their child and the other parent. Is one parent bad-mouthing the other in front of the kids? Does one parent tend to start arguments when picking up or dropping off the child with the other parent?

The more cooperative parents will usually have an edge in a custody dispute. And parents who are obviously trying to alienate a child from the other parent—or who just can’t refrain from undermining the other parent’s relationship with the kids—will learn the hard way that judges don’t look kindly on that type of behavior.

Parents’ Relationships With Their Children Before Divorce

Judges will look at each parent’s history of taking care of and spending time with their children on a day-to-day basis. Sometimes, parents who haven’t been much involved with their kids’ lives suddenly develop a strong desire to spend more time with the children once the marriage has ended.

In many cases, this desire is sincere, and a judge will respect it—especially if the parent has been dedicated to parenting during the separation period. But the judge will definitely take some time to evaluate the situation to make sure that a parent isn’t requesting custody primarily to win out over the other parent, and that a parent with little experience of daily caretaking can follow through with those new-found wishes.

History of Abuse or Neglect

Obviously, when there’s clear evidence of child abuse or neglect, a judge will limit the abusive parent’s contact with the children. If judges do award visitation in these cases, it will usually be supervised and structured in a way to protect the children from future emotional or physical harm.

Domestic violence against the other parent will also play into custody decisions, particularly when the kids have witnessed the abuse..

Children’s Need for Continuity and Stability

When it comes to children, judges are big on the status quo, because most of them believe that piling more change on top of the traumatic transition of divorce generally isn’t good for kids. Among other things, judges may look at the child’s ties to the current school and community.

So if you’re arguing that things are working fine, you’ve got a leg up on a spouse who’s arguing for a major change in the custody or visitation schedule that’s already in place.

Several other factors that judges consider are related to children’s need for stability after divorce.

Each Parent’s Living Situation

There’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg dilemma surrounding the issue of which parent keeps the family home and how that affects custody. Often, the judge awards the home to the parent with physical custody of the children, because that will provide stability and continuity in the children’s lives. Other times, the judge awards custody to the parent who’s going to stay in the family home, for the same reason.

Whether you’re the “out-parent” (the one who isn’t staying in the family home), or neither you nor your ex were able to keep the house after divorce, you’ll need to prove that your current living situation would be a good place for the children to spend a lot of time if you want primary or shared custody. Don’t expect to get that result if you’re crashing in your best friend’s guest room while you get back on your feet after the divorce.

At the same time, most judges will try to avoid penalizing parents who can’t afford a nice home with an ideal set-up for kids. (It’s also worth noting that the child support laws in many states allow judges to consider the differences in living standards between the parents’ households when they’re deciding on the amount of child support in cases where the kids will spend time with both parents.)

How Far Apart the Parents Live From Each Other

The proximity of your home to your spouse’s may also factor in to the judge’s custody decision. The closer you are to each other, the more likely it is that the judge will order a time-sharing plan that gives both parents significant time with the kids. When parents live in the same community, their children can continue with their same social, sports, and religious activities regardless of which parent they’re staying with on which day. Geographical distance becomes more important as kids get older and maintain stronger bonds with their friends.

It’s also less taxing on the children to go back and forth between parents who don’t live far apart.

The Children’s Preferences

Depending on the state and the children’s maturity, judges may talk to kids to find out where they want to live and how much time they want to spend with each parent. Or judges may learn about the children’s opinions from a custody evaluator.

Some states require judges to consider children’s custody preferences when they’ve reached a certain age, but they may listen to younger children’s view when it’s appropriate. In other states, the requirement isn’t about the child’s age as much as the ability to express an opinion based on sound reasoning—not on things like which parent will let them stay up late.

Still other states disapprove of bringing the children into custody decisions at all.

Does the Age of a Child Matter in Custody Decisions?

The “tender years” doctrine—the idea that young children should stay with their mothers—has long been officially out of fashion. The gender of the parents is not a factor to be considered in custody decisions, but some states still allow judges to consider the children’s age. And some judges continue to believe that younger children should live with their mothers, especially when the mother has been the primary caregiver. Certainly, it’s not likely that a father would be awarded sole custody of a nursing baby.

We also have the GrandParents Rights To Visit Family Law Packet including the FL-375 Form Needed to File

Best Interest of the Child Standard –

Test for the Factors Weighed by California Courts Under Family Code Sections 3011, 3020, 3040

Parents engaged in custody disputes frequently charge into court with a list of reasons supporting their position that the court should grant them custody of their child rather than the other parent. These same parents frequently leave the courthouse without the orders they requested, wondering why nobody cares about their compelling and well-thought-out list.

Here is the not-so-secret reason nobody cares about that list: the list doesn’t address the factors the court considers when making child custody orders in California. In truth, the list most likely focuses on the faults of the other parent rather than providing the court with any legally relevant information regarding the child.

Checklist for Parents Seeking Custody of Minor Children Under California Family Code 3011, 3020, 3040

The function of the family court is not to change, fix, or judge parents but to dispose of their disputes at a given point in time. California family courts are wholly unconcerned about the personal grievances parents in a custody dispute have against one another. Instead, the courts are guided by the factors and standards of the California Family Code.

Guide to Best Interest Standard – Family Code 3011, 3020, 3040

The Best Interests of the Child Standard (BIC) is not found in only one code section or case; it is a compilation of many different Family Code sections and case law. However, the standard primarily arises out of Family Code 3011, 3020, and 3040. These sections are used by family courts when making and modifying child custody orders.

The child’s best interest depends partly on the health and safety of the child’s mind and body (i.e. mental and physical). The family court considers how well the parents can keep a livable home and meet basic food, clothing, medical, and education needs of the child.

Of course, any issues having to do with drug or alcohol problems, sexual abuse, or any kind of domestic violence will be considered.

If the judge thinks the child is mature enough, the child’s own wishes must be a factor in the decision.

Below, each of the code sections making up the BIC Standard is unraveled:

California Family Code Section 3011 – Welfare of the Child

California Family Code Section 3011 – Welfare of the Child

Family Code 3011 provides a broad non-exhaustive list of factors for California family courts to consider in making a determination of what custody and visitation orders are in the best interests of a child. This section is the root of the commonly referenced “Best Interest Standard” in California family law jurisprudence, and provides a road-map for custody attorneys, child custody mediators, parents, and judges.

While it may seem axiomatic for the court to consider the health, safety, and welfare of a child in making orders regarding where and with whom a child will live, this section mandates the consideration. Section 3011 also creates a rebuttable presumption against awarding custody to parents who have substance abuse problems – implying that the California State Legislature views substance abuse as a crisis directly impacting the safety and well-being of children.

The best interests of the child, as a matter of public policy in California, always trumps the rights and interests of parents. However, Section 3011 also creates protections for parents/guardians seeking custody of a child in family court by giving the court discretion to require independent corroboration as a prerequisite to considering allegations of abuse. A history of abuse may also trigger other presumptions affecting custody of a child under the Family Code, such as those outlined in Family Code 3044 regarding domestic violence findings.

Family Code Section 3011 provides that:

(a) In making a determination of the best interests of the child in a proceeding described in Section 3021, the court shall, among any other factors it finds relevant and consistent with Section 3020, consider all of the following:

(1) The health, safety, and welfare of the child.

(2)(A) A history of abuse by one parent or any other person seeking custody against any of the following:

(i) A child to whom the parent or person seeking custody is related by blood or affinity or with whom the parent or person seeking custody has had a caretaking relationship, no matter how temporary.

(ii) The other parent.

(iii) A parent, current spouse, or cohabitant, of the parent or person seeking custody, or a person with whom the parent or person seeking custody has a dating or engagement relationship.

(B) As a prerequisite to considering allegations of abuse, the court may require independent corroboration, including, but not limited to, written reports by law enforcement agencies, child protective services or other social welfare agencies, courts, medical facilities, or other public agencies or private nonprofit organizations providing services to victims of sexual assault or domestic violence. As used in this paragraph, “abuse against a child” means “child abuse and neglect” as defined in Section 11165.6 of the Penal Code and abuse against any of the other persons described in clause (ii) or (iii) of subparagraph (A) means “abuse” as defined in Section 6203.

(3) The nature and amount of contact with both parents, except as provided in Section 3046.

(4) The habitual or continual illegal use of controlled substances, the habitual or continual abuse of alcohol, or the habitual or continual abuse of prescribed controlled substances by either parent. Before considering these allegations, the court may first require independent corroboration, including, but not limited to, written reports from law enforcement agencies, courts, probation departments, social welfare agencies, medical facilities, rehabilitation facilities, or other public agencies or nonprofit organizations providing drug and alcohol abuse services. As used in this paragraph, “controlled substances” has the same meaning as defined in the California Uniform Controlled Substances Act, Division 10 (commencing with Section 11000) of the Health and Safety Code.

(5)(A) When allegations about a parent pursuant to paragraphs (2) or (4) have been brought to the attention of the court in the current proceeding, and the court makes an order for sole or joint custody to that parent, the court shall state its reasons in writing or on the record. In these circumstances, the court shall ensure that any order regarding custody or visitation is specific as to time, day, place, and manner of transfer of the child as set forth in subdivision (c) of Section 6323.

(B) This paragraph does not apply if the parties stipulate in writing or on the record regarding custody or visitation.

(b) Notwithstanding subdivision (a), the court shall not consider the sex, gender identity, gender expression, or sexual orientation of a parent, legal guardian, or relative in determining the best interests of the child.

Family Courts Cannot Consider Sex, Gender, Gender Identity, Gender Expression, or Sexual Orientation

Arguably the most important take-away from Section 3011 is subsection (b), prohibiting the court from considering a parent or guardian’s sex, gender identity, gender expression, or sexual orientation in determining the best interests of the child.

This subsection coupled with the proclamation of Family Code 3010 that a mother and father are “equally entitled to the custody of the child” expresses the clear California legislative declaration that historical bias in favor of mothers and against LGBTQ parents is not consistent with the public policy of the State of California. This notion is again addressed in Section 3020 and Section 3040 presumably because of the long-standing bias and perceived bias in custody matters.

California Family Code 3020 – Children Should Have Frequent and Continuing Contact with Both Parents and Have a Right to Be Safe and Free From Abuse

The “frequent and continuing contact” language of Section 3020 is commonly utilized by judges, and custody attorneys in family court when requesting and making child custody orders.

At its core, this section is putting California on notice that parents are expected to work together in raising children even when the parents are not in a relationship (i.e. married, dating, living together, etc.), and it is presumed to be in a child’s best interest to see both parents regularly unless there is a legally valid reason (i.e. abuse, substance abuse, etc.) otherwise.

(a) The Legislature finds and declares that it is the public policy of this state to ensure that the health, safety, and welfare of children shall be the court’s primary concern in determining the best interests of children when making any orders regarding the physical or legal custody or visitation of children. The Legislature further finds and declares that children have the right to be safe and free from abuse, and that the perpetration of child abuse or domestic violence in a household where a child resides is detrimental to the health, safety, and welfare of the child.

(b) The Legislature finds and declares that it is the public policy of this state to ensure that children have frequent and continuing contact with both parents after the parents have separated or dissolved their marriage, or ended their relationship, and to encourage parents to share the rights and responsibilities of child rearing in order to effect this policy, except when the contact would not be in the best interests of the child, as provided in subdivisions (a) and (c) of this section and Section 3011.

(c) When the policies set forth in subdivisions (a) and (b) of this section are in conflict, a court’s order regarding physical or legal custody or visitation shall be made in a manner that ensures the health, safety, and welfare of the child and the safety of all family members.

(d) The Legislature finds and declares that it is the public policy of this state to ensure that the sex, gender identity, gender expression, or sexual orientation of a parent, legal guardian, or relative is not considered in determining the best interests of the child.

Family Code 3020 doubles down on Section 3011 by declaring that the chief concern of the State with regard to custody of children is the “best interests” of the minor children.

California Family Code 3040 Grants the Court Wide Discretion to Choose Visitation Schedules for Children

The commonly misconstrued language of Family Code Section 3040, subsection (a)(1), is often incorrectly applied by both litigants and attorneys alike. The plain language seems to create a presumption that it is in the best interest of children for parents to share joint legal and physical custody.

Further reading of the section is necessary to ascertain the true legislative intent, however, as subsection (d) declares that Family Code 3040 does not establish a preference or presumption in favor of joint legal or physical custody, but grants the court and family “the widest” discretion to choose a parenting plan consistent with the best interests of the child (as enumerated in Section 3011).

If no presumption in favor of joint legal and physical custody is created by Section 3040(a), then what does it mean?

Section 3040(a) dictates that the order of preference in granting custody of a child is as follows: first, to the parents of the child; second, if to neither parent, then to someone with whom the child has been living in a stable/wholesome environment; and finally, if to neither parent or someone with whom the child is living, then to any other suitable person who can provide adequate care and guidance to the child. This section can be used to award custody of a child to a step-parent or guardian.

That is to say that California courts will grant custody to a parent before any third party unless it is not in the best interest of the child to do so.

Subsection (a)(1) also creates a mandate on the family court to consider which parent is more likely to facilitate frequent and continuing contact with the other parent. This provision can create problems for parents who are unable to co-parent and parents who engage in alienating behaviors.

Family Code 3040 provides that:

(a) Custody should be granted in the following order of preference according to the best interest of the child as provided in Sections 3011 and 3020:

(1) To both parents jointly pursuant to Chapter 4 (commencing with Section 3080) or to either parent. In making an order granting custody to either parent, the court shall consider, among other factors, which parent is more likely to allow the child frequent and continuing contact with the noncustodial parent, consistent with Sections 3011 and 3020. The court, in its discretion, may require the parents to submit to the court a plan for the implementation of the custody order.

(2) If to neither parent, to the person or persons in whose home the child has been living in a wholesome and stable environment.

(3) To any other person or persons deemed by the court to be suitable and able to provide adequate and proper care and guidance for the child.

(b) The immigration status of a parent, legal guardian, or relative shall not disqualify the parent, legal guardian, or relative from receiving custody under subdivision (a).

(c) The court shall not consider the sex, gender identity, gender expression, or sexual orientation of a parent, legal guardian, or relative in determining the best interest of the child under subdivision (a).

(d) This section establishes neither a preference nor a presumption for or against joint legal custody, joint physical custody, or sole custody, but allows the court and the family the widest discretion to choose a parenting plan that is in the best interest of the child, consistent with this section.

(e) In cases where a child has more than two parents, the court shall allocate custody and visitation among the parents based on the best interest of the child, including, but not limited to, addressing the child’s need for continuity and stability by preserving established patterns of care and emotional bonds. The court may order that not all parents share legal or physical custody of the child if the court finds that it would not be in the best interest of the child as provided in Sections 3011 and 3020.

Applying the Best Interest of the Child Standard

Parents do not have to fight to win. In fact, if the parents have not already agreed on what they want to happen, the court will make them try mediation to work out a custody agreement and a full parenting plan. Only if all else fails will the couple face a family law judge who will make the decisions.

No matter if the judge must force a plan on a couple or approve a child custody agreement they have already drawn up, state law requires that everyone focus on doing what is in the child’s best interest. cited

We also have the GrandParents Rights To Visit Family Law Packet including the FL-375 Form Needed to File

Your Just Read this DETAILED VIEW Click Here to Visit our Resource What Exactly is the Child’s Best Interest in Custody Cases!

Click here to learn What Law is Used in Determining Factor in FAM § 3011 – Determining Best Interest Child – Family Code 3011

To Learn More…. Read MORE Below and click the links Below

Abuse & Neglect – The Reporters (Police, D.A & Medical & the Bad Actors)

Mandated Reporter Laws – Nurses, District Attorney’s, and Police should listen up

If You Would Like to Learn More About: The California Mandated Reporting LawClick Here

To Read the Penal Code § 11164-11166 – Child Abuse or Neglect Reporting Act – California Penal Code 11164-11166Article 2.5. (CANRA) Click Here

Mandated Reporter formMandated ReporterFORM SS 8572.pdf – The Child Abuse

ALL POLICE CHIEFS, SHERIFFS AND COUNTY WELFARE DEPARTMENTS INFO BULLETIN:

Click Here Officers and DA’s for (Procedure to Follow)

It Only Takes a Minute to Make a Difference in the Life of a Child learn more below

You can learn more here California Child Abuse and Neglect Reporting Law its a PDF file

Learn More About True Threats Here below….

We also have the The Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) – 1st Amendment

CURRENT TEST = We also have the The ‘Brandenburg test’ for incitement to violence – 1st Amendment

We also have the The Incitement to Imminent Lawless Action Test– 1st Amendment

We also have the True Threats – Virginia v. Black is most comprehensive Supreme Court definition – 1st Amendment

We also have the Watts v. United States – True Threat Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Clear and Present Danger Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Gravity of the Evil Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Elonis v. United States (2015) – Threats – 1st Amendment

Learn More About What is Obscene…. be careful about education it may enlighten you

We also have the Miller v. California – 3 Prong Obscenity Test (Miller Test) – 1st Amendment

We also have the Obscenity and Pornography – 1st Amendment

Learn More About Police, The Government Officials and You….

$$ Retaliatory Arrests and Prosecution $$

We also have the Brayshaw v. City of Tallahassee – 1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Publius v. Boyer-Vine –1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, Florida (2018) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Nieves v. Bartlett (2019) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Hartman v. Moore (2006) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

We also have the Reichle v. Howards (2012) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

Freedom of the Press – Flyers, Newspaper, Leaflets, Peaceful Assembly – 1$t Amendment – Learn More Here

Vermont’s Top Court Weighs: Are KKK Fliers – 1st Amendment Protected Speech

We also have the Insulting letters to politician’s home are constitutionally protected, unless they are ‘true threats’ – Letters to Politicians Homes – 1st Amendment

We also have the First Amendment Encyclopedia very comprehensive – 1st Amendment

ARE PEOPLE LYING ON YOU? CAN YOU PROVE IT? IF YES…. THEN YOU ARE IN LUCK!

Penal Code 118 PC – California Penalty of “Perjury” Law

Federal Perjury – Definition by Law

Penal Code 132 PC – Offering False Evidence

Penal Code 134 PC – Preparing False Evidence

Penal Code 118.1 PC – Police Officer$ Filing False Report$

Spencer v. Peters– Police Fabrication of Evidence – 14th Amendment

Penal Code 148.5 PC – Making a False Police Report in California

Penal Code 115 PC – Filing a False Document in California

Sanctions and Attorney Fee Recovery for Bad Actors

FAM § 3027.1 – Attorney’s Fees and Sanctions For False Child Abuse Allegations – Family Code 3027.1 – Click Here

FAM § 271 – Awarding Attorney Fees– Family Code 271 Family Court Sanction Click Here

Awarding Discovery Based Sanctions in Family Law Cases – Click Here

FAM § 2030 – Bringing Fairness & Fee Recovery – Click Here

Zamos v. Stroud – District Attorney Liable for Bad Faith Action – Click Here

Mi$Conduct – Pro$ecutorial Mi$Conduct

Prosecutor$

Criminal Motions § 1:9 – Motion for Recusal of Prosecutor

Pen. Code, § 1424 – Recusal of Prosecutor

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

Mi$Conduct – Judicial Mi$Conduct

Judge$

Prosecution Of Judges For Corrupt Practice$

Code of Conduct for United States Judge$

Disqualification of a Judge for Prejudice

Judicial Immunity from Civil and Criminal Liability

Recusal of Judge – CCP § 170.1 – Removal a Judge – How to Remove a Judge

l292 Disqualification of Judicial Officer – C.C.P. 170.6 Form

How to File a Complaint Against a Judge in California?

Commission on Judicial Performance – Judge Complaint Online Form

Why Judges, District Attorneys or Attorneys Must Sometimes Recuse Themselves

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

Misconduct by Government Know Your Rights Click Here (must read!)

Under 42 U.S.C. $ection 1983 – Recoverable Damage$

42 U.S. Code § 1983 – Civil Action for Deprivation of Right$

$ection 1983 Lawsuit – How to Bring a Civil Rights Claim

18 U.S. Code § 242 – Deprivation of Right$ Under Color of Law

18 U.S. Code § 241 – Conspiracy against Right$

$uing for Misconduct – Know More of Your Right$

Police Misconduct in California – How to Bring a Lawsuit

Malicious Prosecution / Prosecutorial Misconduct – Know What it is!

New Supreme Court Ruling – makes it easier to sue police

Possible courses of action Prosecutorial Misconduct

Misconduct by Judges & Prosecutor – Rules of Professional Conduct

Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

What is Sua Sponte and How is it Used in a California Court?

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors

and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

PARENT CASE LAW

RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR CHILDREN &

YOUR CONSTITUIONAL RIGHT$ + RULING$

YOU CANNOT GET BACK TIME BUT YOU CAN HIT THOSE IMMORAL NON CIVIC MINDED PUNKS WHERE THEY WILL FEEL YOU = THEIR BANK

9.3 Section 1983 Claim Against Defendant as (Individuals) —

14th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

Amdt5.4.5.6.2 – Parental and Children’s Rights –

5th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

9.32 – Interference with Parent / Child Relationship –

14th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

California Civil Code Section 52.1

Interference with exercise or enjoyment of individual rights

Parent’s Rights & Children’s Bill of Rights

SCOTUS RULINGS FOR YOUR PARENT RIGHTS

SEARCH of our site for all articles relating for PARENTS RIGHTS Help!

Child’s Best Interest in Custody Cases

Are You From Out of State (California)? FL-105 GC-120(A)

Declaration Under Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction and Enforcement Act (UCCJEA)

GRANDPARENT CASE LAW

Do Grandparents Have Visitation Rights? If there is an Established Relationship then Yes

Third “PRESUMED PARENT” Family Code 7612(C) – Requires Established Relationship Required

Cal State Bar PDF to read about Three Parent Law –

The State Bar of California family law news issue4 2017 vol. 39, no. 4.pdf

Distinguishing Request for Custody from Request for Visitation

Troxel v. Granville, 530 U.S. 57 (2000) – Grandparents – 14th Amendment

Child’s Best Interest in Custody Cases

9.32 Particular Rights – Fourteenth Amendment – Interference with Parent / Child Relationship

When is a Joinder in a Family Law Case Appropriate? – Reason for Joinder

Joinder In Family Law Cases – CRC Rule 5.24

GrandParents Rights To Visit

Family Law Packet OC Resource Center

Family Law Packet SB Resource Center

Motion to vacate an adverse judgment

Mandatory Joinder vs Permissive Joinder – Compulsory vs Dismissive Joinder

When is a Joinder in a Family Law Case Appropriate?

Kyle O. v. Donald R. (2000) 85 Cal.App.4th 848

Punsly v. Ho (2001) 87 Cal.App.4th 1099

Zauseta v. Zauseta (2002) 102 Cal.App.4th 1242

S.F. Human Servs. Agency v. Christine C. (In re Caden C.)

DUE PROCESS READS>>>>>>

Due Process vs Substantive Due Process learn more HERE

Understanding Due Process – This clause caused over 200 overturns in just DNA alone Click Here

Mathews v. Eldridge – Due Process – 5th & 14th Amendment Mathews Test – 3 Part Test– Amdt5.4.5.4.2 Mathews Test

“Unfriending” Evidence – 5th Amendment

At the Intersection of Technology and Law

We also have the Introducing TEXT & EMAIL Digital Evidence in California Courts – 1st Amendment

so if you are interested in learning about Introducing Digital Evidence in California State Courts

click here for SCOTUS rulings

Retrieving Evidence / Internal Investigation Case

Conviction Integrity Unit (“CIU”) of the Orange County District Attorney OCDA – Click Here

Fighting Discovery Abuse in Litigation – Forensic & Investigative Accounting – Click Here

Orange County Data, BodyCam, Police Report, Incident Reports,

and all other available known requests for data below:

APPLICATION TO EXAMINE LOCAL ARREST RECORD UNDER CPC 13321 Click Here

Learn About Policy 814: Discovery Requests OCDA Office – Click Here

Request for Proof In-Custody Form Click Here

Request for Clearance Letter Form Click Here

Application to Obtain Copy of State Summary of Criminal HistoryForm Click Here

Request Authorization Form Release of Case Information – Click Here

Texts / Emails AS EVIDENCE: Authenticating Texts for California Courts

Can I Use Text Messages in My California Divorce?

Two-Steps And Voila: How To Authenticate Text Messages

How Your Texts Can Be Used As Evidence?

California Supreme Court Rules: Text Messages Sent on Private Government Employees Lines Subject to Open Records Requests

case law: City of San Jose v. Superior Court – Releasing Private Text/Phone Records of Government Employees

Public Records Practices After the San Jose Decision

The Decision Briefing Merits After the San Jose Decision

CPRA Public Records Act Data Request – Click Here

Here is the Public Records Service Act Portal for all of CALIFORNIA Click Here

Appealing/Contesting Case/Order/Judgment/Charge/ Suppressing Evidence

First Things First: What Can Be Appealed and What it Takes to Get Started – Click Here

Options to Appealing– Fighting A Judgment Without Filing An Appeal Settlement Or Mediation

Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 1008 Motion to Reconsider

Penal Code 1385 – Dismissal of the Action for Want of Prosecution or Otherwise

Penal Code 1538.5 – Motion To Suppress Evidence in a California Criminal Case

CACI No. 1501 – Wrongful Use of Civil Proceedings

Penal Code “995 Motions” in California – Motion to Dismiss

WIC § 700.1 – If Court Grants Motion to Suppress as Evidence

Suppression Of Exculpatory Evidence / Presentation Of False Or Misleading Evidence – Click Here

Notice of Appeal — Felony (Defendant) (CR-120) 1237, 1237.5, 1538.5(m) – Click Here

Cleaning Up Your Record

Penal Code 851.8 PC – Certificate of Factual Innocence in California

SB 393: The Consumer Arrest Record Equity Act – 851.87 – 851.92 & 1000.4 – 11105 – CARE ACT

Expungement California – How to Clear Criminal Records Under Penal Code 1203.4 PC

Cleaning Up Your Criminal Record in California (focus OC County)

Governor Pardons Click Here for the Details

How to Get a Sentence Commuted (Executive Clemency) in California

How to Reduce a Felony to a Misdemeanor – Penal Code 17b PC Motion

Vacate a Criminal Conviction in California – Penal Code 1473.7 PC

Epic Criminal / Civil Right$ SCOTUS Help – Click Here

Epic Criminal / Civil Right$ SCOTUS Help – Click Here

Epic Parents SCOTUS Ruling – Parental Right$ Help – Click Here

Epic Parents SCOTUS Ruling – Parental Right$ Help – Click Here

Judge’s & Prosecutor’s Jurisdiction– SCOTUS RULINGS on

Judge’s & Prosecutor’s Jurisdiction– SCOTUS RULINGS on

Prosecutional Misconduct – SCOTUS Rulings re: Prosecutors

Prosecutional Misconduct – SCOTUS Rulings re: Prosecutors

Family Treatment Court Best Practice Standards

Download Here this Recommended Citation

Please take time to learn new UPCOMING

The PROPOSED Parental Rights Amendment

to the US CONSTITUTION Click Here to visit their site

The proposed Parental Rights Amendment will specifically add parental rights in the text of the U.S. Constitution, protecting these rights for both current and future generations.

The Parental Rights Amendment is currently in the U.S. Senate, and is being introduced in the U.S. House.