Miller v. California – 3 Prong Obscenity Test – 1st Amendment

Miller v. California – Obscenity – 1st Amendment

Miller v. California (1973)

by Warren E. Burger & William O. Douglas

What is obscenity? What is meant by “prurient interest”? What is the difference between sexuality and obscenity? What was the Hicklin test? Why is obscene speech not protected by the First

Amendment? What is the definition of “obscenity” in Miller? How does the SLAPS test in Miller provide more guidance to juries than the “utterly without redeeming social value” test in Memoirs? How does Justice Burger’s opinion in Miller reflect the principle of federalism? What are the precedents of Paris Adult Theatre v. Slaton (1973), and New York v. Ferber(1982)?

Introduction

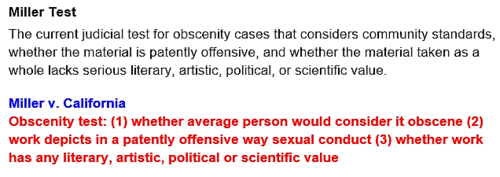

Like libel and fighting words, obscenity is a content-based category of expression that is not protected by the First Amendment. That is to say, authorities may punish obscene material without infringing upon First Amendment rights. The difficulty, however, is defining obscenity, a problem that has plagued the Court. How does one distinguish between sexual expression that might be protected and obscene material that is unprotected? Attempting to answer this question, Justice Potter Stewart once curtly explained, “I know it when I see it.” Until the mid-twentieth century, the Court adopted the Hicklin test, a Victorian common-law standard that judged obscenity in terms of “whether the tendency of the matter is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences.” Under this standard, sexual expression could be restricted based on the reactions of those most susceptible to sexual suggestion, whether the pervert or the prude. Furthermore, under the Hicklin test, a work could be deemed obscene if only an isolated portion of it, rather than the work as a whole, affected this susceptible person. In, Roth v. United States (1957), the Supreme Court rejected the Hicklin test and replaced it with a new standard for judging obscenity. The Roth test defined obscene material as that which “deals with sex in a manner appealing to the prurient interest” and is “utterly without redeeming social importance.” Under Roth, ideas having even the slightest redeeming social importance are protected. The Roth test and a subsequent iteration of it in Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966) were superseded by Miller v. California, decided 5–4, and the companion case Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton (1973), which remain the controlling precedents for obscenity. Notably, in a nod to federalism and a change from Roth, the new obscenity standard of Miller was a state and local standard, not a national one. The Court also replaced the “utterly without redeeming social value” of the Memoirs test with the SLAPS test (serious, literary, artistic, political, scientific value). Nine years after Miller, in New York v. Ferber (1982), the Court banned child pornography as a category excluded from First Amendment protection.

Source: 413 U.S. 15, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/413/15.

cited https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/miller-v-california/

In Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973), the Supreme Court upheld the prosecution of a California publisher for the distribution of obscene materials. In doing so, it established the test used to determine whether expressive materials cross the line into unprotected obscenity. The Miller test remains the guide in this area of First Amendment jurisprudence.

Miller convicted for distributing obscenity

In California, Covina-based publisher Marvin Miller was called in some circles the “King of Smut.” In this case, he was prosecuted in 1968 for mailing advertisements for four books — Intercourse, Man–Woman, Sex Orgies Illustrated, and An Illustrated History of Pornography — and a film entitled Marital Intercourse. A jury then convicted Miller under a California law prohibiting the distribution of obscenity, and his conviction was affirmed by a California appeals court. Miller appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, contending that the advertisements in question were not obscene. The Court affirmed his conviction 5-4.

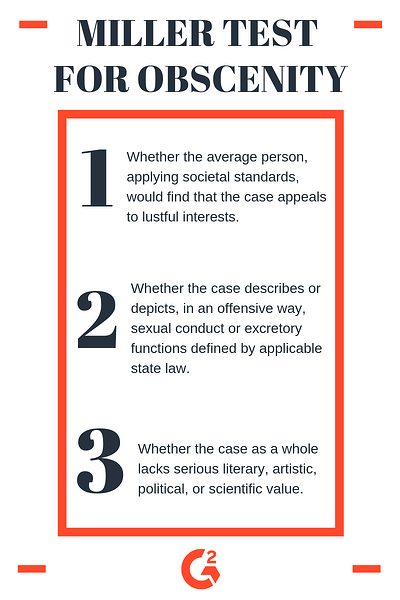

Burger established three-part obscenity test

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger established a three-part test for juries in obscenity cases: “Whether the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the work taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest; whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” The three parts of the test soon became known, in short, as the prurient interest, patently offensive, and SLAPS prongs.

The Miller standard differed from the Court’s previous obscenity standard as articulated in Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966). A plurality in Memoirs had established that any material designated as obscene had to be “utterly without any redeeming social value,” but in Miller the Court relaxed the standard for prosecutors by requiring the material to have some “serious value.” The new standard granted “greater discretion to law enforcement agencies, judges and jurors to decide whether, under local community standards, material should be condemned as obscene” (Mathews 1973: A1).

First Amendment does not require national community standard

Burger rejected the notion that the First Amendment requires a national community standard, writing: “It is neither realistic nor constitutionally sound to read the First Amendment as requiring that the people of Maine or Mississippi accept public depiction of conduct found tolerable in Las Vegas, or New York City.” He did note that only materials that “depict or describe patently offensive ‘hard core’ sexual conduct specifically defined by the regulating state law” constituted obscenity.

Justice William O. Douglas dissented, writing that obscenity cases “have no business in the courts.” Justice William J. Brennan Jr., joined by Justices Potter Stewart and Thurgood Marshall, also wrote a dissent, referring readers to his dissent in the companion case of Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton (1973), in which he argued that obscenity laws could not be drafted consistently with the First Amendment.

The Miller test remains the dominant test for both state and federal obscenity prosecutions. Criticism continues to the notion of applying “contemporary community standards.” For example, the 9th Circuit in United States v. Kilbride (2009) wrote that “a national community standard must be applied in regulating obscene speech on the Internet, including obscenity disseminated via email.”

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.

cited https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/401/miller-v-california

Legal Principle at Issue

Whether, consistent with the First Amendment, unsolicited mass mailings to advertise books containing explicit pictures of sexual activities can be criminally prosecuted.

Action

Vacated and remanded. Petitioning party received a favorable disposition.

Facts/Syllabus

Appellant was convicted of mailing unsolicited sexually explicit material in violation of a California statute that approximately incorporated the obscenity test formulated in Memoirs v. Massachusetts, 383 U. S. 413, 383 U. S. 418 (plurality opinion). The trial court instructed the jury to evaluate the materials by the contemporary community standards of California. Appellant’s conviction was affirmed on appeal. In lieu of the obscenity criteria enunciated by the Memoirs plurality, it is held:

1. Obscene material is not protected by the First Amendment. Roth v. United States, 354 U. S. 476, reaffirmed. A work may be subject to state regulation where that work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest in sex; portrays, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and, taken as a whole, does not have serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. Pp. 413 U. S. 23-24.

2. The basic guidelines for the trier of fact must be: (a) whether “the average person, applying contemporary community standards” would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest, Roth, supra, at 354 U. S. 489, (b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law, and (c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. If a state obscenity law is thus limited, First Amendment values are adequately protected by ultimate independent appellate review of constitutional claims when necessary. Pp. 413 U. S. 24-25.

3. The test of “utterly without redeeming social value” articulated in Memoirs, supra, is rejected as a constitutional standard. Pp. 413 U. S. 24-25.

4. The jury may measure the essentially factual issues of prurient appeal and patent offensiveness by the standard that prevails in the forum community, and need not employ a “national standard.” Pp. 413 U. S. 30-34.

cited https://www.thefire.org/supreme-court/miller-v-california

To Learn More…. Read MORE Below and click the links

Learn More About True Threats Here below….

We also have the The Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) – 1st Amendment

CURRENT TEST = We also have the The ‘Brandenburg test’ for incitement to violence – 1st Amendment

We also have the The Incitement to Imminent Lawless Action Test– 1st Amendment

We also have the True Threats – Virginia v. Black is most comprehensive Supreme Court definition – 1st Amendment

We also have the Watts v. United States – True Threat Test – 1st Amendment

We also have theClear and Present Danger Test – 1st Amendment

We also have theGravity of the Evil Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Elonis v. United States (2015) – Threats – 1st Amendment

Learn More About What is Obscene….

We also have the Miller v. California – 3 Prong Obscenity Test (Miller Test) – 1st Amendment

We also have the Obscenity and Pornography – 1st Amendment

Learn More About Police, The Government Officials and You….

We also have theBrayshaw v. City of Tallahassee – 1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have thePublius v. Boyer-Vine –1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, Florida (2018) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Nieves v. Bartlett (2019) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Freedom of the Press – Flyers, Newspaper, Leaflets, Peaceful Assembly – 1st Amendment

We also have the Insulting letters to politician’s home are constitutionally protected, unless they are ‘true threats’ – 1st Amendment

We also have the Introducing TEXT & EMAILDigital Evidencein California Courts – 1st Amendment

We also have the First Amendment Encyclopedia very comprehensive – 1st Amendment

ARE PEOPLE LYING ON YOU? CAN YOU PROVE IT? IF YES…. THEN YOU ARE IN LUCK!

We also have the Penal Code 118 PC – California Penalty of “Perjury” Law

We also have theFederal Perjury – Definition by Law

We also have the Penal Code 132 PC – Offering False Evidence

We also have the Penal Code 134 PC – Preparing False Evidence

We also have thePenal Code 118.1 PC – Police Officers Filing False Reports

We also have the Spencer v. Peters– Police Fabrication of Evidence – 14th Amendment

We also have the Penal Code 148.5 PC – Making a False Police Report in California

We also have the Penal Code 115 PC – Filing a False Document in California

Know Your Rights Click Here (must read!)

Under 42 U.S.C. $ection 1983 – Recoverable Damage$

42 U.S. Code § 1983– Civil Action for Deprivation of Right$

$ection 1983 Lawsuit – How to Bring a Civil Rights Claim

18 U.S. Code § 242 – Deprivation of Right$ Under Color of Law

18 U.S. Code § 241 – Conspiracy against Right$

$uing for Misconduct – Know More of Your Right$

Police Misconduct in California – How to Bring a Lawsuit

New Supreme Court Ruling – makes it easier to sue police

RELATIONSHIPWITH YOURCHILDREN& YOURCONSTITUIONAL RIGHT$ + RULING$

YOU CANNOT GET BACK TIME BUT YOU CAN HIT THOSE PUNKS WHERE THEY WILL FEEL YOU = THEIR BANK

We also have the 9.3 Section 1983 Claim Against Defendant as (Individuals) — 14th Amendment thisCODE PROTECTS all US CITIZENS

We also have the Amdt5.4.5.6.2 – Parental and Children’s Rights 5th Amendment thisCODE PROTECTS all US CITIZENS

We also have the 9.32 – Interference with Parent / Child Relationship – 14th Amendment thisCODE PROTECTS all US CITIZENS

We also have the California Civil Code Section 52.1Interference with exercise or enjoyment of individual rights

We also have the Parent’s Rights & Children’s Bill of RightsSCOTUS RULINGS FOR YOUR PARENT RIGHTS

We also have a SEARCH of our site for all articles relatingfor PARENTS RIGHTS Help!

Contesting / Appeal an Order / Judgment / Charge

Options to Appealing– Fighting A Judgment Without Filing An Appeal Settlement Or Mediation

Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 1008 Motion to Reconsider

Penal Code 1385 – Dismissal of the Action for Want of Prosecution or Otherwise

Penal Code 1538.5 – Motion To Suppress Evidence in a California Criminal Case

CACI No. 1501 – Wrongful Use of Civil Proceedings

Penal Code “995 Motions” in California – Motion to Dismiss

WIC § 700.1 – If Court Grants Motion to Suppress as Evidence

Epic Criminal / Civil Rights SCOTUS Help – Click Here

Epic Criminal / Civil Rights SCOTUS Help – Click Here

Epic Parents SCOTUS Ruling – Parental Rights Help – Click Here

Epic Parents SCOTUS Ruling – Parental Rights Help – Click Here