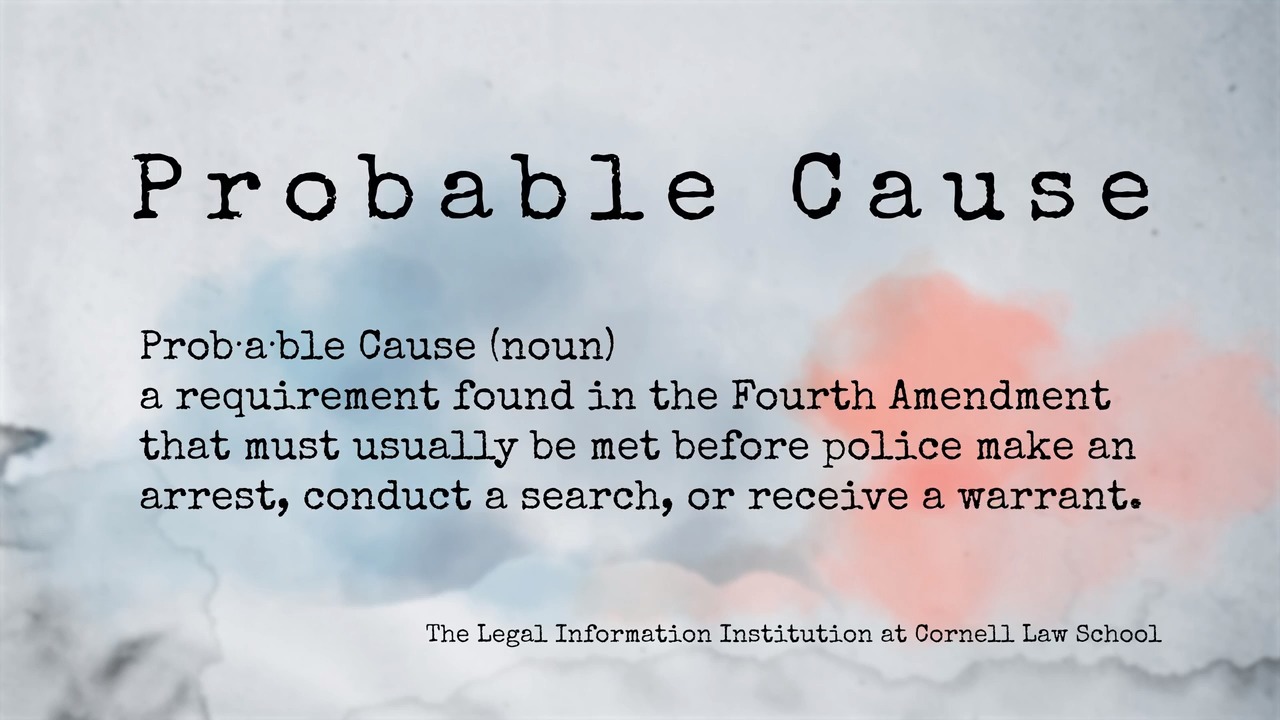

What is Probable Cause? and.. How is Probable Cause Established?

Probable Cause

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Probable Cause.—The concept of “probable cause” is central to the meaning of the warrant clause. Neither the Fourth Amendment nor the federal statutory provisions relevant to the area define “probable cause”; the definition is entirely a judicial construct. An applicant for a warrant must present to the magistrate facts sufficient to enable the officer himself to make a determination of probable cause. “In determining what is probable cause . . . [w]e are concerned only with the question whether the affiant had reasonable grounds at the time of his affidavit . . . for the belief that the law was being violated on the premises to be searched; and if the apparent facts set out in the affidavit are such that a reasonably discreet and prudent man would be led to believe that there was a commission of the offense charged, there is probable cause justifying the issuance of a warrant.”116 Probable cause is to be determined according to “the factual and practical considerations of everyday life on which reasonable and prudent men, not legal technicians, act.”117 Warrants are favored in the law and their use will not be thwarted by a hypertechnical reading of the supporting affidavit and supporting testimony.118 For the same reason, reviewing courts will accept evidence of a less “judicially competent or persuasive character than would have justified an officer in acting on his own without a warrant.”119 Courts will sustain the determination of probable cause so long as “there was substantial basis for [the magistrate] to conclude that” there was probable cause.120

Much litigation has concerned the sufficiency of the complaint to establish probable cause. Mere conclusory assertions are not enough.121 In United States v. Ventresca,122 however, an affidavit by a law enforcement officer asserting his belief that an illegal distillery was being operated in a certain place, explaining that the belief was based upon his own observations and upon those of fellow investigators, and detailing a substantial amount of these personal observations clearly supporting the stated belief, was held to be sufficient to constitute probable cause. “Recital of some of the underlying circumstances in the affidavit is essential,” the Court said, observing that “where these circumstances are detailed, where reason for crediting the source of the information is given, and when a magistrate has found probable cause,” the reliance on the warrant process should not be deterred by insistence on too stringent a showing.123

Requirements for establishing probable cause through reliance on information received from an informant has divided the Court in several cases. Although involving a warrantless arrest, Draper v. United States124 may be said to have begun the line of cases. A previously reliable, named informant reported to an officer that the defendant would arrive with narcotics on a particular train, and described the clothes he would be wearing and the bag he would be carrying; the informant, however, gave no basis for his information. FBI agents met the train, observed that the defendant fully fit the description, and arrested him. The Court held that the corroboration of part of the informer’s tip established probable cause to support the arrest. A case involving a search warrant, Jones v. United States,125 apparently considered the affidavit as a whole to see whether the tip plus the corroborating information provided a substantial basis for finding probable cause, but the affidavit also set forth the reliability of the informer and sufficient detail to indicate that the tip was based on the informant’s personal observation. Aguilar v. Texas126 held insufficient an affidavit that merely asserted that the police had “reliable information from a credible person” that narcotics were in a certain place, and held that when the affiant relies on an informant’s tip he must present two types of evidence to the magistrate. First, the affidavit must indicate the informant’s basis of knowledge—the circumstances from which the informant concluded that evidence was present or that crimes had been committed—and, second, the affiant must present information that would permit the magistrate to decide whether or not the informant was trustworthy. Then, in Spinelli v. United States,127 the Court applied Aguilar in a situation in which the affidavit contained both an informant’s tip and police information of a corroborating nature.

The Court rejected the “totality” test derived from Jones and held that the informant’s tip and the corroborating evidence must be separately considered. The tip was rejected because the affidavit contained neither any information which showed the basis of the tip nor any information which showed the informant’s credibility. The corroborating evidence was rejected as insufficient because it did not establish any element of criminality but merely related to details which were innocent in themselves. No additional corroborating weight was due as a result of the bald police assertion that defendant was a known gambler, although the tip related to gambling. Returning to the totality test, however, the Court in United States v. Harris128 approved a warrant issued largely on an informer’s tip that over a two-year period he had purchased illegal whiskey from the defendant at the defendant’s residence, most recently within two weeks of the tip. The affidavit contained rather detailed information about the concealment of the whiskey, and asserted that the informer was a “prudent person,” that defendant had a reputation as a bootlegger, that other persons had supplied similar information about him, and that he had been found in control of illegal whiskey within the previous four years. The Court determined that the detailed nature of the tip, the personal observation thus revealed, and the fact that the informer had admitted to criminal behavior by his purchase of whiskey were sufficient to enable the magistrate to find him reliable, and that the supporting evidence, including defendant’s reputation, could supplement this determination.

subject and returned to the “totality of the circumstances” approach to evaluate probable cause based on an informant’s tip in Illinois v. Gates.129 The main defect of the two-part test, Justice Rehnquist concluded for the Court, was in treating an informant’s reliability and his basis for knowledge as independent requirements. Instead, “a deficiency in one may be compensated for, in determining the overall reliability of a tip, by a strong showing as to the other, or by some other indicia of reliability.”130 In evaluating probable cause, “[t]he task of the issuing magistrate is simply to make a practical, commonsense decision whether, given all the circumstances set forth in the affidavit before him, including the ‘veracity’ and ‘basis of knowledge’ of persons supplying hearsay information, there is a fair probability that contraband or evidence of a crime will be found in a particular place.”131

116 Dumbra v. United States, 268 U.S. 435, 439, 441 (1925). “[T]he term ‘probable cause’ . . . means less than evidence which would justify condemnation.” Lock v. United States, 11 U.S. (7 Cr.) 339, 348 (1813). See Steele v. United States, 267 U.S. 498, 504–05 (1925). It may rest upon evidence that is not legally competent in a criminal trial, Draper v. United States, 358 U.S. 307, 311 (1959), and it need not be sufficient to prove guilt in a criminal trial. Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160, 173 (1949). See United States v. Ventresca, 380 U.S. 102, 107–08 (1965). An “anticipatory” warrant does not violate the Fourth Amendment as long as there is probable cause to believe that the condition precedent to execution of the search warrant will occur and that, once it has occurred, “there is a fair probability that contraband or evidence of a crime will be found in a specified place.” United States v. Grubbs, 547 U.S. 90, 95 (2006), quoting Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213, 238 (1983). “An anticipatory warrant is ‘a warrant based upon an affidavit showing probable cause that at some future time (but not presently) certain evidence of a crime will be located at a specified place.’” 547 U.S. at 94.

117 Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160, 175 (1949).

118 United States v. Ventresca, 380 U.S. 102, 108–09 (1965).

119 Jones v. United States, 362 U.S. 257, 270–71 (1960). Similarly, the preference for proceeding by warrant leads to a stricter rule for appellate review of trial court decisions on warrantless stops and searches than is employed to review probable cause to issue a warrant. Ornelas v. United States, 517 U.S. 690 (1996) (determinations of reasonable suspicion to stop and probable cause to search without a warrant should be subjected to de novo appellate review).

120 Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U.S. 108, 111 (1964). It must be emphasized that the issuing party “must judge for himself the persuasiveness of the facts relied on by a [complainant] to show probable cause.” Giordenello v. United States, 357 U.S. 480, 486 (1958). An insufficient affidavit cannot be rehabilitated by testimony after issuance concerning information possessed by the affiant but not disclosed to the magistrate. Whiteley v. Warden, 401 U.S. 560 (1971).

121 Byars v. United States, 273 U.S. 28 (1927) (affiant stated he “has good reason to believe and does believe” that defendant has contraband materials in his possession); Giordenello v. United States, 357 U.S. 480 (1958) (complainant merely stated his conclusion that defendant had committed a crime). See also Nathanson v. United States, 290 U.S. 41 (1933).

122 380 U.S. 102 (1965).

123 380 U.S. at 109.

124 358 U.S. 307 (1959). For another case applying essentially the same probable cause standard to warrantless arrests as govern arrests by warrant, see McCray v. Illinois, 386 U.S. 300 (1967) (informant’s statement to arresting officers met Aguilar probable cause standard). See also Whitely v. Warden, 401 U.S. 560, 566 (1971) (standards must be “at least as stringent” for warrantless arrest as for obtaining warrant).

125 362 U.S. 257 (1960).

126 378 U.S. 108 (1964).

127 393 U.S. 410 (1969). Both concurring and dissenting Justices recognized tension between Draper and Aguilar.See id. at 423 (Justice White concurring), id. at 429 (Justice Black dissenting and advocating the overruling of Aguilar).

128 403 U.S. 573 (1971). See also Adams v. Williams, 407 U.S. 143, 147 (1972) (approving warrantless stop of motorist based on informant’s tip that “may have been insufficient” under Aguilar and Spinelli as basis for warrant).

129 462 U.S. 213 (1983). Justice Rehnquist’s opinion of the Court was joined by Chief Justice Burger and by Justices Blackmun, Powell, and O’Connor. Justices Brennan, Marshall, and Stevens dissented.

130 462 U.S. at 213.

131 462 U.S. at 238. For an application of the Gates “totality of the circumstances” test to the warrantless search of a vehicle by a police officer, see, e.g. Florida v. Harris, 568 U.S. ___, No. 11–817, slip op. (2013). source

Probable Cause: Definition, Legal Requirements

What Is Probable Cause?

Probable cause is a requirement in criminal law that must be met before a police officer can make an arrest, conduct a search, seize property, or get a warrant.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Probable cause is a requirement in criminal law that must be met before a police officer can make an arrest, conduct a search, seize property, or get a warrant.

- The probable cause requirement stems from the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which states that citizens have the right to be free from unreasonable government intrusion into their persons, homes, and businesses.

- Illinois v. Gates is a landmark case in the evolution of probable cause and search warrants.1

Understanding Probable Cause

Probable cause requires that the police have more than just suspicion—but not to the extent of absolute certainty—that a suspect committed a crime. The police must have a reasonable basis in the context of the totality of the circumstances for believing that a crime was committed. The probable cause requirement stems from the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which provides for the right of citizens to be free from unreasonable government intrusion into their persons, homes, and businesses.

Probable cause is important in two aspects of criminal law:

- Police must have probable cause before they search a person or property, and before they arrest a person.

- The court must find that there is probable cause to believe the defendant committed the crime before they are prosecuted.

When a search warrant is in effect, police must generally search only for the items described in the warrant, although they can seize any contraband or evidence of other crimes that they find. However, if the search is deemed to be illegal, any evidence found becomes subject to the “exclusionary rule” and cannot be used against the defendant in court.

What is malicious prosecution California?

CACI No. 1501. Wrongful Use of Civil Proceedings

“The tort of malicious prosecution lies to compensate an individual who is maliciously hailed into court and forced to defend against a fabricated cause of action.” Pace v Hillcrest Motor Co. (1980) 101 CA3d 476, 478. To establish the cause of action, a plaintiff must plead and prove that (CACI 1500, 1501):

Malicious prosecution is when someone sues or files criminal charges against someone else without probable cause and with harmful intent. It can be a civil or criminal lawsuit.

- Providing false evidence to the police that someone committed a crime

- Suing someone for hurting them even if they never caused harm

- A police officer or government official filing criminal charges against someone because of personal animosity, bias, or another reason outside the interests of justice

“The tort of malicious prosecution lies to compensate an individual who is maliciously hailed into court and forced to defend against a fabricated cause of action.” Pace v Hillcrest Motor Co. (1980) 101 CA3d 476, 478.

CA Penal Code § 170 (2022) – Misuse of the Warrant System – Crimes Against Public Justice

CA Penal Code § 170 (2022) click here

Penal Code § 170 . Every person who maliciously and without probable cause procures a search warrant or warrant of arrest to be issued and executed, is guilty of a misdemeanor.

In United States criminal law, probable cause is the standard[1] by which police authorities have reason to obtain a warrant for the arrest of a suspected criminal or the issuing of a search warrant. There is no universally accepted definition or formulation for probable cause. One traditional definition, which comes from the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1964 decision Beck v. Ohio, is when “whether at [the moment of arrest] the facts and circumstances within [an officer’s] knowledge and of which they had reasonably trustworthy information [are] sufficient to warrant a prudent [person] in believing that [a suspect] had committed or was committing an offense.”[2]

It is also the standard by which grand juries issue criminal indictments. The principle behind the standard is to limit the power of authorities to perform random or abusive searches (unlawful search and seizure), and to promote lawful evidence gathering and procedural form during criminal arrest and prosecution. The standard also applies to personal or property searches.[3]

The Supreme Court in Berger v. New York 1967 explained that the purpose of the probable cause requirement of the Fourth Amendment is to keep the state out of constitutionally protected areas until it has reason to believe that a specific crime has been or is being committed.[4] The term probable cause itself comes from the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Probable in this case may relate to statistical probability or to a general standard of common behavior and customs. The context of the word probable here is not exclusive to community standards, and could partially derive from its use in formal mathematical statistics as some have suggested;[5] but cf. probō, Latin etymology.

In U.S. immigration proceedings, the “reason to believe” standard has been interpreted as equivalent to probable cause.[6]

Probable cause should not be confused with reasonable suspicion, which is the required criteria to perform a Terry stop in the United States of America. The criteria for reasonable suspicion are less strict than those for probable cause. source

The Constitution protects you from having your person or property searched without probable cause. But what is probable cause?

This guide explains how probable cause is defined and what probable cause requirements means for you. You’ll also see some examples of probable cause so you can better understand how this legal rule applies in the real world.

The Probable Cause Requirement

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects people against being unlawfully searched or unfairly arrested by police. The text of the amendment reads as follows:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

Because of this amendment, police cannot conduct a search without probable cause of wrongdoing. And they cannot arrest you unless there is probable cause of a crime being committed.

If you are searched without probable cause, any evidence collected must be suppressed. This means it cannot be used against you in court. If you are arrested without probable cause, the arrest is considered invalid and any evidence collected as a result of it will be suppressed.

Amdt4.5.3 Probable Cause Requirement

Fourth Amendment:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The concept of probable cause

is central to the meaning of the Warrant Clause. Neither the Fourth Amendment nor the federal statutory provisions relevant to the area define probable cause

; the definition is entirely a judicial construct. An applicant for a warrant must present to the magistrate facts sufficient to enable the officer himself to make a determination of probable cause. In determining what is probable cause . . . [w]e are concerned only with the question whether the affiant had reasonable grounds at the time of his affidavit . . . for the belief that the law was being violated on the premises to be searched; and if the apparent facts set out in the affidavit are such that a reasonably discreet and prudent man would be led to believe that there was a commission of the offense charged, there is probable cause justifying the issuance of a warrant.

1 Probable cause is to be determined according to the factual and practical considerations of everyday life on which reasonable and prudent men, not legal technicians, act.

2 Warrants are favored in the law and their use will not be thwarted by a hypertechnical reading of the supporting affidavit and supporting testimony.3 For the same reason, reviewing courts will accept evidence of a less judicially competent or persuasive character than would have justified an officer in acting on his own without a warrant.

4 Courts will sustain the determination of probable cause so long as there was substantial basis for [the magistrate] to conclude that

there was probable cause.5

Footnotes

- Jump to essay-1Dumbra v. United States, 268 U.S. 435, 439, 441 (1925).

[T]he term ‘probable cause’. . . means less than evidence which would justify condemnation.

Lock v. United States, 11 U.S. (7 Cr.) 339, 348 (1813). See Steele v. United States, 267 U.S. 498, 504–05 (1925). It may rest upon evidence that is not legally competent in a criminal trial, Draper v. United States, 358 U.S. 307, 311 (1959), and it need not be sufficient to prove guilt in a criminal trial. Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160, 173 (1949). See United States v. Ventresca, 380 U.S. 102, 107–08 (1965). Ananticipatory

warrant does not violate the Fourth Amendment as long as there is probable cause to believe that the condition precedent to execution of the search warrant will occur and that, once it has occurred,there is a fair probability that contraband or evidence of a crime will be found in a specified place.

United States v. Grubbs, 547 U.S. 90, 95 (2006), quoting Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213, 238 (1983).An anticipatory warrant is ‘a warrant based upon an affidavit showing probable cause that at some future time (but not presently) certain evidence of a crime will be located at a specified place.’

547 U.S. at 94. - Jump to essay-2Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160, 175 (1949).

- Jump to essay-3United States v. Ventresca, 380 U.S. 102, 108–09 (1965).

- Jump to essay-4Jones v. United States, 362 U.S. 257, 270–71 (1960). Similarly, the preference for proceeding by warrant leads to a stricter rule for appellate review of trial court decisions on warrantless stops and searches than is employed to review probable cause to issue a warrant. Ornelas v. United States, 517 U.S. 690 (1996) (determinations of reasonable suspicion to stop and probable cause to search without a warrant should be subjected to de novo appellate review).

- Jump to essay-5Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U.S. 108, 111 (1964). It must be emphasized that the issuing party

must judge for himself the persuasiveness of the facts relied on by a [complainant] to show probable cause.

Giordenello v. United States, 357 U.S. 480, 486 (1958). An insufficient affidavit cannot be rehabilitated by testimony after issuance concerning information possessed by the affiant but not disclosed to the magistrate. Whiteley v. Warden, 401 U.S. 560 (1971). - source

read ALL OF THE FOURTH AMENDMENT BELOW JUST CLICK THE LINK

Fourth Amendment – Search and Seizure

What Is the Definition of Probable Cause?

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, probable cause exists when the “facts and circumstances” that police officers know about, based on “reasonably trustworthy information, are sufficient in themselves to warrant a belief by a man of reasonable caution that a crime is being committed.”

In other words, if a reasonably cautious person was provided with the information the police officers had at the time, that person would have a valid reason to believe that a crime was taking place. This reasonable belief of criminal activity is sufficient to justify either a search or an arrest.

Probable cause is determined based on the totality of the circumstances, so all available information can be considered in deciding if there is valid justification to either conduct a search or to arrest a suspect.

Satisfying the Probable Cause Requirement

Law enforcement officials must obtain a search warrant before conducting a search when it is possible to do so. A judge should only issue a search warrant if there is probable cause, which means there is enough credible information to suggest evidence of a crime will be discovered during the search.

Law enforcement officials must also obtain an arrest warrant before arresting someone when it is possible and practical to do so. Again, there must be probable cause or credible information suggesting someone most likely committed a criminal offense before an arrest warrant is issued.

Warrantless searches and warrantless arrests can occur in certain circumstances such as when police see evidence of a crime in plain view or when there are exigent circumstances because failure to act could result in the destruction of evidence or harm to others.

When a warrantless search or arrest occurs, law enforcement officials need to provide proof of probable cause after the fact. If law enforcement cannot satisfy the probable cause requirement, the evidence collected will be suppressed or the arrest will be deemed invalid.

Exceptions to the Probable Cause Requirement

There are very limited exceptions when evidence is still admissible even if it was obtained without probable cause.

Exceptions include circumstances where police were acting in good faith, but there was a problem they were unaware of. For example, if police arrest someone because they believe there is a valid warrant, but it turns out a mistake was made and there wasn’t, then evidence collected after the arrest would still be admissible.

Examples of Probable Cause

There are many different examples of probable cause that could justify a search or justify an arrest. Here are some common examples:

- A law enforcement officer pulls someone over for a traffic violation. The officer notices drug paraphernalia on the front seat or notices the driver is slurring their words and is visibly intoxicated and likely committing a DUI. The drug paraphernalia or the obvious intoxication provides probable cause for a search of the vehicle and/or for an arrest.

- A law enforcement officer observes someone pointing a gun at a convenience store employee in an apparent robbery. This unlawful act the officer observed provides probable cause for arrest.

- A law enforcement officer visits a person’s home after a report of domestic violence and observes weapons in the home and bruises on the alleged victim. This provides probable cause for a search of the home and, if the available evidence creates a reasonable suspicion of a crime, also probable cause for an arrest.

Probable cause may come from officers directly observing evidence suggestive of criminal activity or from credible reports of criminal misconduct from trustworthy sources.

What If an Arrest or Search Occurs Without Probable Cause?

If you believe you were searched or arrested without probable cause, you can argue your constitutional rights were violated.

If a judge determines there was no probable cause and no exceptions such as the good faith exception apply, evidence collected as a result of the unlawful search or unlawful arrest will not be admissible in court against you.

In some cases, you may also have grounds for a lawsuit if you were searched or arrested without probable cause. However, suing the government can be a challenge even in situations where you believe your rights were violated as a result of sovereign immunity rules.

When you suspect a violation of your rights, it is very important to talk with an experienced attorney. If you have been charged with a crime, a lawyer can also help you to determine if you may be able to get evidence suppressed based on a constitutional violation. You should reach out to an attorney ASAP to protect yourself as you navigate the criminal justice system. source

California Penal Code § 170 – Misuse of the Warrant System – Crimes Against Public Justice

Probable Cause – Definition

Probable cause is a requirement found in the Fourth Amendment that must usually be met before police make an arrest, conduct a search, or receive a warrant. Courts usually find probable cause when there is a reasonable basis for believing that a crime may have been committed (for an arrest) or when evidence of the crime is present in the place to be searched (for a search). Under exigent circumstances, probable cause can also justify a warrantless search or seizure. Persons arrested without a warrant are required to be brought before a competent authority shortly after the arrest for a prompt judicial determination of probable cause.

Overview

Constitutional Basis

Although the Fourth Amendment states that “no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause”, it does not specify what “probable cause” actually means. The Supreme Court has attempted to clarify the meaning of the term on several occasions, while recognizing that probable cause is a concept that is imprecise, fluid and very dependent on context. In Illinois v. Gates, the Court favored a flexible approach, viewing probable cause as a “practical, non-technical” standard that calls upon the “factual and practical considerations of everyday life on which reasonable and prudent men […] act”.1 Courts often adopt a broader, more flexible view of probable cause when the alleged offenses are serious.

Application to Arrests

The Fourth Amendment requires that any arrest be based on probable cause, even when the arrest is made pursuant to an arrest warrant. Whether or not there is probable cause typically depends on the totality of the circumstances, meaning everything that the arresting officers know or reasonably believe at the time the arrest is made.2 However, probable cause remains a flexible concept, and what constitutes the “totality of the circumstances” often depends on how the court interprets the reasonableness standard.3

A lack of probable cause will render a warrantless arrest invalid, and any evidence resulting from that arrest (physical evidence, confessions, etc.) will have to be suppressed.4 A narrow exception applies when an arresting officer, as a result of a mistake by court employees, mistakenly and in good faith believes that a warrant has been issued. In this case, notwithstanding the lack of probable cause, the exclusionary rule does not apply and the evidence obtained may be admissible.5 Unlike court clerks, prosecutors are part of a law enforcement team and are not “court employees” for purposes of the good-faith exception to the exclusionary rule.6

Application to Search Warrants

Probable cause exists when there is a fair probability that a search will result in evidence of a crime being discovered.7 For a warrantless search, probable cause can be established by in-court testimony after the search. In the case of a warrant search, however, an affidavit or recorded testimony must support the warrant by indicating on what basis probable cause exists.8

A judge may issue a search warrant if the affidavit in support of the warrant offers sufficient credible information to establish probable cause.9 There is a presumption that police officers are reliable sources of information, and affidavits in support of a warrant will often include their observations.10 When this is the case, the officers’ experience and training become relevant factors in assessing the existence of probable cause.11 Information from victims or witnesses, if included in an affidavit, may be important factors as well.12

The good faith exception that applies to arrests also applies to search warrants: when a defect renders a warrant constitutionally invalid, the evidence does not have to be suppressed if the officers acted in good faith.13 Courts evaluate an officer’s good faith by looking at the nature of the error and how the warrant was executed.14

Probable Cause in the Digital Age

While the Fourth Amendment’s probable cause requirement has historically been applied to physical seizures of tangible property, the issue of searches and seizures as applied to data has come to the Supreme Court’s attention in recent years.

In Riley v California (2014), the Supreme Court held: “The police generally may not, without a warrant, search digital information on a cellphone seized from an individual who has been arrested.” This would seem to group cell phones in with traditional items subject to traditional court tests and rules for searches and seizures.

Riley, however, did not end the inquiry into digital data’s interaction with the Fourth Amendment. For the 2018 term, the Supreme Court has agreed to hear Carpenter v. United States. Carpenter, accused of several robberies, was arrested after “his phone company shared data on his whereabouts with law-enforcement agents.”

Mr. Carpenter is challenging the “constitutionality of the Stored Communications Act, a law permitting phone companies to divulge information when there are ‘specific and articulable facts’ that are ‘relevant and material’ to a criminal investigation.” His complaint states that “his privacy rights under the Fourth Amendment were violated when his phone company shared data on his whereabouts with law-enforcement agents.” This case will likely have a significant impact on the role that probable cause plays in the ability of data companies to share user information with law enforcement.

- 1. See Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213, 232 (1983).

- 2. United States v. Humphries, 372 F.3d 653, 657 (4th Cir. 2004).

- 3. Prosecutor’s Manual for Arrest, Search and Seizure, § 6-6(b) (2004).

- 4. See Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961), at 648, 655.

- 5. See Ariz. v. Evans, 514 U.S. 1 (1995).

- 6. People v. Boyer, 305 Ill. App. 3d 374 (1999), at 379-80.

- 7. See Gates, 462 U.S. at 238.

- 8. Whiteley v. Warden, 401 U.S. 560, 564 (1971).

- 9. Prosecutor’s Manual for Arrest, Search and Seizure, § 3-2(c) (2004).

- 10. See Franks v. Delaware, 438 U.S. 154, 171 (1978).

- 11. See United States v. Mick, 263 F.3d 553, 566 (6th Cir. 2001).

- 12. See United States v. Schaefer, 87 F.3d 562, 566 (1st Cir. 1996).

- 13. See United States v. White, 356 F.3d 865 (8th Cir. 2004).

- 14. See, e.g., United States v. Clark, 638 F.3d 89, 100–05 (2d Cir. 2011)

- source

Supreme Court Interpretation of Probable Cause

The Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures generally means law enforcement must have a warrant or “probable cause” to search someone’s property or make an arrest. But probable cause can come in many forms, and what qualifies as probable cause is something the Supreme Court has grappled with for many years.

What the Fourth Amendment Says

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

What is probable cause?

How Does Law Enforcement Establish Probable Cause?

United States Library of Congress, The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation

Much litigation has concerned the sufficiency of the complaint to establish probable cause. Mere conclusory assertions are not enough.1 In United States v. Ventresca,2 however, an affidavit by a law enforcement officer asserting his belief that an illegal distillery was being operated in a certain place, explaining that the belief was based upon his own observations and upon those of fellow investigators, and detailing a substantial amount of these personal observations clearly supporting the stated belief, was held to be sufficient to constitute probable cause. Recital of some of the underlying circumstances in the affidavit is essential, the Court said, observing that where these circumstances are detailed, where reason for crediting the source of the information is given, and when a magistrate has found probable cause, the reliance on the warrant process should not be deterred by insistence on too stringent a showing.3

Probable Cause Based on Tips from Informants

Requirements for establishing probable cause through reliance on information received from an informant has divided the Court in several cases. Although involving a warrantless arrest, Draper v. United States4 may be said to have begun the line of cases. A previously reliable, named informant reported to an officer that the defendant would arrive with narcotics on a particular train, and described the clothes he would be wearing and the bag he would be carrying; the informant, however, gave no basis for his information. FBI agents met the train, observed that the defendant fully fit the description, and arrested him. The Court held that the corroboration of part of the informer’s tip established probable cause to support the arrest. A case involving a search warrant, Jones v. United States,5 apparently considered the affidavit as a whole to see whether the tip plus the corroborating information provided a substantial basis for finding probable cause, but the affidavit also set forth the reliability of the informer and sufficient detail to indicate that the tip was based on the informant’s personal observation. Aguilar v. Texas6 held insufficient an affidavit that merely asserted that the police had reliable information from a credible person that narcotics were in a certain place, and held that when the affiant relies on an informant’s tip he must present two types of evidence to the magistrate. First, the affidavit must indicate the informant’s basis of knowledge—the circumstances from which the informant concluded that evidence was present or that crimes had been committed—and, second, the affiant must present information that would permit the magistrate to decide whether or not the informant was trustworthy. Then, in Spinelli v. United States,7 the Court applied Aguilar in a situation in which the affidavit contained both an informant’s tip and police information of a corroborating nature.

The Court rejected the totality test derived from Jones and held that the informant’s tip and the corroborating evidence must be separately considered. The tip was rejected because the affidavit contained neither any information which showed the basis of the tip nor any information which showed the informant’s credibility. The corroborating evidence was rejected as insufficient because it did not establish any element of criminality but merely related to details which were innocent in themselves. No additional corroborating weight was due as a result of the bald police assertion that defendant was a known gambler, although the tip related to gambling. Returning to the totality test, however, the Court in United States v. Harris8 approved a warrant issued largely on an informer’s tip that over a two-year period he had purchased illegal whiskey from the defendant at the defendant’s residence, most recently within two weeks of the tip. The affidavit contained rather detailed information about the concealment of the whiskey, and asserted that the informer was a prudent person, that defendant had a reputation as a bootlegger, that other persons had supplied similar information about him, and that he had been found in control of illegal whiskey within the previous four years. The Court determined that the detailed nature of the tip, the personal observation thus revealed, and the fact that the informer had admitted to criminal behavior by his purchase of whiskey were sufficient to enable the magistrate to find him reliable, and that the supporting evidence, including defendant’s reputation, could supplement this determination.

The Court expressly abandoned the two-part Aguilar–Spinelli test and returned to the totality of the circumstances approach to evaluate probable cause based on an informant’s tip in Illinois v. Gates.9 The main defect of the two-part test, Justice Rehnquist concluded for the Court, was in treating an informant’s reliability and his basis for knowledge as independent requirements. Instead, a deficiency in one may be compensated for, in determining the overall reliability of a tip, by a strong showing as to the other, or by some other indicia of reliability.10 In evaluating probable cause, the task of the issuing magistrate is simply to make a practical, commonsense decision whether, given all the circumstances set forth in the affidavit before him, including the ‘veracity’ and ‘basis of knowledge’ of persons supplying hearsay information, there is a fair probability that contraband or evidence of a crime will be found in a particular place.11

Probable Cause vs. First Amendment Rights

Where the warrant process is used to authorize the seizure of books and other items that may be protected by the First Amendment, the Court has required the government to observe more exacting standards than in other cases.12 Seizure of materials arguably protected by the First Amendment is a form of prior restraint that requires strict observance of the Fourth Amendment. At a minimum, a warrant is required, and additional safeguards may be required for large-scale seizures. Thus, in Marcus v. Search Warrant,13 the seizure of 11,000 copies of 280 publications pursuant to warrant issued ex parte by a magistrate who had not examined any of the publications but who had relied on the conclusory affidavit of a policeman was voided. Failure to scrutinize the materials and to particularize the items to be seized was deemed inadequate, and it was further noted that police were provided with no guide to the exercise of informed discretion, because there was no step in the procedure before seizure designed to focus searchingly on the question of obscenity.14 A state procedure that was designed to comply with Marcus by the presentation of copies of books to be seized to the magistrate for his scrutiny prior to issuance of a warrant was nonetheless found inadequate by a plurality of the Court, which concluded that since the warrant here authorized the sheriff to seize all copies of the specified titles, and since [appellant] was not afforded a hearing on the question of the obscenity even of the seven novels [seven of 59 listed titles were reviewed by the magistrate] before the warrant issued, the procedure was constitutionally deficient.15

Confusion remains, however, about the necessity for and the character of prior adversary hearings on the issue of obscenity. In a later decision the Court held that, with adequate safeguards, no pre-seizure adversary hearing on the issue of obscenity is required if the film is seized not for the purpose of destruction as contraband (the purpose in Marcus and A Quantity of Books), but instead to preserve a copy for evidence.16 It is constitutionally permissible to seize a copy of a film pursuant to a warrant as long as there is a prompt post-seizure adversary hearing on the obscenity issue. Until there is a judicial determination of obscenity, the Court advised, the film may continue to be exhibited; if no other copy is available either a copy of it must be made from the seized film or the film itself must be returned.17

The seizure of a film without the authority of a constitutionally sufficient warrant is invalid; seizure cannot be justified as incidental to arrest, as the determination of obscenity may not be made by the officer himself.18 Nor may a warrant issue based solely on the conclusory assertions of the police officer without any inquiry by the magistrate into the factual basis for the officer’s conclusions.19 Instead, a warrant must be supported by affidavits setting forth specific facts in order that the issuing magistrate may ‘focus searchingly on the question of obscenity.’20 This does not mean, however, that a higher standard of probable cause is required in order to obtain a warrant to seize materials protected by the First Amendment. Our reference in Roaden to a ‘higher hurdle of reasonableness’ was not intended to establish a ‘higher’ standard of probable cause for the issuance of a warrant to seize books or films, but instead related to the more basic requirement, imposed by that decision, that the police not rely on the ‘exigency’ exception to the Fourth Amendment warrant requirement, but instead obtain a warrant from a magistrate.’21

In Stanford v. Texas,22 the Court voided a seizure of more than 2,000 books, pamphlets, and other documents pursuant to a warrant that merely authorized the seizure of books, pamphlets, and other written instruments concerning the Communist Party of Texas. The constitutional requirement that warrants must particularly describe the ‘things to be seized’ is to be accorded the most scrupulous exactitude when the ‘things’ are books, and the basis for their seizure is the ideas which they contain. . . . No less a standard could be faithful to First Amendment freedoms.23

However, the First Amendment does not bar the issuance or execution of a warrant to search a newsroom to obtain photographs of demonstrators who had injured several policemen, although the Court appeared to suggest that a magistrate asked to issue such a warrant should guard against interference with press freedoms through limits on the type, scope, and intrusiveness of the search.24

More on the Fourth Amendment

- Unreasonable Seizures of Property

- Students’ Rights Against Search and Seizure: New Jersey v. TLO

- The Exclusionary Rule: Mapp v. Ohio

Footnotes

1. Byars v. United States, 273 U.S. 28 (1927) (affiant stated he has good reason to believe and does believe that defendant has contraband materials in his possession); Giordenello v. United States, 357 U.S. 480 (1958) (complainant merely stated his conclusion that defendant had committed a crime). See also Nathanson v. United States, 290 U.S. 41 (1933).

2. 380 U.S. 102 (1965).

3. 380 U.S. at 109.

4. 8 U.S. 307 (1959). For another case applying essentially the same probable cause standard to warrantless arrests as govern arrests by warrant, see McCray v. Illinois, 386 U.S. 300 (1967) (informant’s statement to arresting officers met Aguilar probable cause standard). See also Whiteley v. Warden, 401 U.S. 560, 566 (1971) (standards must be at least as stringent for warrantless arrest as for obtaining warrant).

5. 362 U.S. 257 (1960).

6. 378 U.S. 108 (1964).

7. 393 U.S. 410 (1969). Both concurring and dissenting Justices recognized the tension between Draper and Aguilar. See id. at 423 (Justice White concurring), id. at 429 (Justice Black dissenting and advocating the overruling of Aguilar).

8. 403 U.S. 573 (1971). See also Adams v. Williams, 407 U.S. 143, 147 (1972) (approving warrantless stop of motorist based on informant’s tip that may have been insufficient under Aguilar and Spinelli as basis for warrant).

9. 462 U.S. 213 (1983). Justice Rehnquist’s opinion of the Court was joined by Chief Justice Burger and by Justices Blackmun, Powell, and O’Connor. Justices Brennan, Marshall, and Stevens dissented.

10. 462 U.S. at 213.

11. 462 U.S. at 238. For an application of the Gates totality of the circumstances test to the warrantless search of a vehicle by a police officer, see, e.g. Florida v. Harris, 568 U.S. 237 (2013).

12. Marcus v. Search Warrant, 367 U.S. 717, 730–31 (1961); Stanford v. Texas, 379 U.S. 476, 485 (1965). For First Amendment implications of seizures under the Federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), see First Amendment: Obscenity and Prior Restraint.

13. 367 U.S. 717 (1961). See Kingsley Books v. Brown, 354 U.S. 436 (1957).

14. Marcus v. Search Warrant, 367 U.S. 717, 732 (1961).

15. A Quantity of Books v. Kansas, 378 U.S. 205, 210 (1964).

16. Heller v. New York, 413 U.S. 483 (1973).

17. Id. at 492–93. But cf. New York v. P.J. Video, Inc., 475 U.S. 868, 875 n.6 (1986), rejecting the defendant’s assertion, based on Heller, that only a single copy rather than all copies of allegedly obscene movies should have been seized pursuant to warrant.

18. Roaden v. Kentucky, 413 U.S. 496 (1973). See also Lo-Ji Sales v. New York, 442 U.S. 319 (1979); Walter v. United States, 447 U.S. 649 (1980). These special constraints are inapplicable when obscene materials are purchased, and there is consequently no Fourth Amendment search or seizure. Maryland v. Macon, 472 U.S. 463 (1985).

19. Lee Art Theatre, Inc. v. Virginia, 392 U.S. 636, 637 (1968) (per curiam).

20. New York v. P.J. Video, Inc., 475 U.S. 868, 873–74 (1986) (quoting Marcus v. Search Warrant, 367 U.S. 717, 732 (1961)).

21. New York v. P.J. Video, Inc., 475 U.S. 868, 875 n.6 (1986).

22. 379 U.S. 476 (1965).

23. 379 U.S. at 485–86. See also Marcus v. Search Warrant, 367 U.S. 717, 723 (1961).

24. Zurcher v. Stanford Daily, 436 U.S. 547 (1978). See id. at 566 (containing suggestion mentioned in text), and id. at 566 (Justice Powell concurring) (more expressly adopting that position). In the Privacy Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 96-440, 94 Stat. 1879 (1980), 42 U.S.C. § 2000aa, Congress provided extensive protection against searches and seizures not only of the news media and news people but also of others engaged in disseminating communications to the public, unless there is probable cause to believe the person protecting the materials has committed or is committing the crime to which the materials relate.

What Is Reasonable Doubt?

Reasonable doubt is legal terminology referring to insufficient evidence that prevents a judge or jury from convicting a defendant of a crime. It is the traditional standard of proof that must be exceeded to secure a guilty verdict in a criminal case in a court of law.

In a criminal case, it is the job of the prosecution to convince the jury that the defendant is guilty of the crime with which he has been charged and, therefore, should be convicted. The phrase “beyond a reasonable doubt” means that the evidence presented and the arguments put forward by the prosecution establish the defendant’s guilt so clearly that they must be accepted as fact by any rational person.

If the jury cannot say with certainty based on the evidence presented that the defendant is guilty, then there is reasonable doubt and they are obligated to return a non-guilty verdict.

The Reasonable Doubt Standard

Penal Code Title 7, Chapter 2, Section 1096 of the California Penal Code states that a defendant in a criminal trial must be proven guilty to a moral certainty and beyond a reasonable doubt.

Section 1096 also states that a defendant is presumed innocent until the contrary is proven. If there is a reasonable doubt about the defendant’s guilt, they are entitled to an acquittal.

1096. A defendant in a criminal action is presumed to be innocent until the contrary is proved, and in case of a reasonable doubt whether his or her guilt is satisfactorily shown, he or she is entitled to an acquittal, but the effect of this presumption is only to place upon the state the burden of proving him or her guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Reasonable doubt is defined as follows: “It is not a mere possible doubt; because everything relating to human affairs is open to some possible or imaginary doubt. It is that state of the case, which, after the entire comparison and consideration of all the evidence, leaves the minds of jurors in that condition that they cannot say they feel an abiding conviction of the truth of the charge.” source

“Beyond a reasonable doubt” means that the prosecution must convince the jury that there is no other reasonable explanation that can come from the evidence presented at trial. In other words, the jury must be virtually certain of the defendant’s guilt in order to render a guilty verdict.

California law establishes standards which must be met when making an arrest. Section 836 of Title 3, Chapter 5 (“Making of Arrest”) of the California Penal Code (PC) states that a peace officer may make an arrest in obedience to a warrant, or may, without a warrant, arrest a person:

• Whenever he/she has reasonable cause to believe that the person to be arrested has committed a public offense in his or her presence; or

• When a person arrested has committed a felony, although not in his or her presence; or

• Whenever he/she has reasonable cause to believe that the person to be arrested has committed a felony, whether or not a felony has in fact been committed.

As defined by Black”s Law Dictionary, reasonable or probable cause is the state of facts which would lead a reasonable person to believe and suspect that the person sought is guilty of a crime. In other words, there must be more evidence for than against the prospect that the suspect has committed a crime, yet reserving some possibility for doubt. Case law pursuant to PC Section 836 further states that probable cause does not require evidence to convict but only to show that the person should stand trial.

Pursuant to California Penal Code Section 836, peace officers are authorized to make an arrest based on probable cause. As such, the Police must believe that there is more evidence for than against the prospect that the person sought is guilty of a crime, yet reserving some possibility for doubt. source

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Reasonable doubt is insufficient evidence that prevents a judge or jury from convicting a defendant of a crime.

- If it cannot be proved without a doubt that a defendant in a criminal case is guilty, then that person should not be convicted.

- Each juror must walk into the courtroom presuming the accused is innocent and it is the job of the prosecutor to convince them otherwise.

- Reasonable doubt is used exclusively in criminal cases because the consequences of a conviction are severe.

- Other commonly used standards of proof in criminal cases are probable cause, reasonable belief and reasonable suspicion, and credible evidence.

Understanding Reasonable Doubt

Under U.S. law, a defendant is considered innocent until proven guilty. Reasonable doubt stems from insufficient evidence. If it cannot be proved without a doubt that the defendant is guilty, that person should not be convicted. Verdicts do not necessarily reflect the truth, they reflect the evidence presented. A defendant’s actual innocence or guilt may be an abstraction.

Beyond a reasonable doubt is the highest standard of proof used in any court of law and is widely accepted around the world. It is used exclusively in criminal cases because the consequences of a conviction are severe—a criminal conviction could deprive the defendant of liberty or even life.

Difference Between Belief And Certainty

It isn’t unusual for a juror to believe that the defendant is a criminal but not be convinced with certainty that they committed the particular crime they are charged with. That isn’t good enough to find the defendant guilty.

Reasonable doubt comes from certainty rather than belief. Belief and instinct are important in many instances in life but cannot be used to convict a defendant if not based on fact.2

Unreasonable Doubt

The reasonable doubt standard forces jurors to ignore doubts considered unreasonable when determining if a defendant is guilty. Unreasonable doubt, which often stems from the possibility that nonexistent or unpresented evidence might explain a defendant’s actions and lead to exoneration, is not enough to acquit the defendant.3

Exculpatory Evidence

Evidence favorable to the defendant in a criminal trial can also create reasonable doubt as to whether the accused committed the crime. The defendant’s team should not be viewed with more skepticism than the prosecutor’s team. Each shred of evidence should be given the same consideration. This is important as any reasonable doubt, however small, that the defendant did not do it is grounds for an acquittal.4

Other Standards of Proof

Other commonly used standards of proof in criminal cases are:

- Probable Cause: A requirement found in the Fourth Amendment that the police have more than just suspicion that a suspect committed a crime before making an arrest, conducting a search, or serving a warrant.5

- Reasonable Belief and reasonable suspicion: A reasonable presumption by a police officer that a crime was, is, or will be committed. This is more than a hunch and less than probable cause and is used to determine the legality of a police officer’s decision to take action.

- Credible Evidence: Evidence that is deemed worthy of being presented in a court and to the jury.

Meanwhile, evidentiary standards in civil cases include:

- Clear and convincing evidence: The judge or jurors have concluded that there is a high probability that the facts of the case as presented by one party represent the truth. The standard of clear and convincing evidence is used in some civil cases, and it may appear in some aspects of a criminal case, such as a decision on whether a defendant is fit to stand trial.6 The language appears in several U.S. state laws.

- Preponderance of the evidence: Both sides have presented their cases, and one side seems more likely to be true. Most civil cases require a “preponderance of the evidence,” as this is a lower standard of proof.

Presumption of Innocence

The criminal justice system seeks to unearth the truth, convict the guilty, and let the innocent walk free. In order for this to work, each juror must walk into the courtroom presuming the accused is innocent.7

“It is better that 100 guilty persons should escape than one innocent person should suffer.”—Benjamin Franklin 8

This presumption requires that jurors have a skeptical mindset that must be overcome before they can reach a guilty verdict. The jurors must not just want to believe something or be swayed by prejudices. They must view each shred of evidence presented by the prosecution with skepticism.

Why Is Reasonable Doubt Important?

The reasonable doubt standard aims to reduce the chances of an innocent person being convicted. Criminal cases can result in hefty convictions, including death or life sentences, so a person should only be charged if the jurors are 100% confident, based on the evidence presented, of their guilt.

How Do You Prove Reasonable Doubt?

The jurors must walk into the courtroom presuming the accused is innocent. Reasonable doubt exists unless the prosecution can prove that the accused is guilty. This can be achieved by supplying evidence and inviting people to testify on the stand.

What Are the Three Burdens of Proof?

The three burdens of proof for criminal cases are “beyond a reasonable doubt,” “probable cause,” and “reasonable suspicion.”

What Is the Difference Between Doubt and Reasonable Doubt?

A doubt can be considered reasonable when it’s connected to evidence or an absence of evidence. Sympathies or prejudices are not reasonable grounds for doubt.

The Bottom Line

Reasonable doubt is an important legal standard that strives to prevent innocent people from getting convicted for a crime they didn’t commit. If it cannot be proved without a reasonable doubt that the defendant is guilty, then they should not be convicted of the crime as charged. source

Reasonable suspicion

Overview

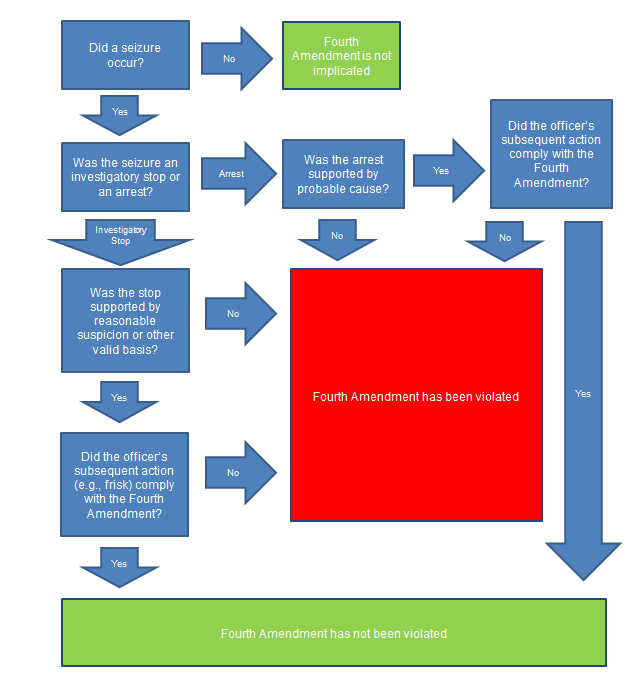

Reasonable suspicion is a standard used in criminal procedure. Reasonable suspicion is used in determining the legality of a police officer’s decision to perform a search.

When an officer stops someone to search the person, courts require that the officer has either a search warrant, probable cause to search, or a reasonable suspicion to search. In descending order of what gives an officer the broadest authority to perform a search, courts have found that the order is search warrant, probable cause, and then reasonable suspicion.

Reasonable Suspicion As Applied to a Stop & Frisk

Probable Cause vs Reasonable suspicion

Definition of Probable Cause – Probable cause means that a reasonable person would believe that a crime was in the process of being committed, had been committed, or was going to be committed.

Legal Repercussions of Probable Cause – Probable cause is enough for a search or arrest warrant. It is also enough for a police officer to make an arrest if he sees a crime being committed.

Definition of Reasonable Suspicion – Reasonable suspicion has been defined by the United States Supreme Court as “the sort of common-sense conclusion about human behavior upon which practical people . . . are entitled to rely.” Further, it has defined reasonable suspicion as requiring only something more than an “unarticulated hunch.” It requires facts or circumstances that give rise to more than a bare, imaginary, or purely conjectural suspicion.

Reasonable suspicion means that any reasonable person would suspect that a crime was in the process of being committed, had been committed or was going to be committed very soon.

Legal Repercussions of Reasonable Suspicion – If an officer has reasonable suspicion in a situation, he may frisk or detain the suspect briefly. Reasonable suspicion does not allow for the searching of a person or a vehicle unless the person happens to be on school property. Reasonable suspicion is not enough for an arrest or a search warrant.

Stop and Frisk – In Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968), the court recognized that a limited stop and frisk of an individual could be conducted without a warrant based on less than probable cause. The stop must be based on a reasonable, individualized suspicion based on articulable facts, and the frisk is limited to a pat-down for weapons. An anonymous tip that a person is carrying a gun is not, by itself, sufficient to justify a stop and frisk. Florida v. J.L., 529 U.S. 266 (2000).

Florida v. Bostick 501 U.S. 429, 437 (1991) – A person’s refusal to cooperate is not sufficient for reasonable suspicion.

Illinois v. Wardlow, 528 U.S. 119, 124-25 (2000). – A person’s flight in a high crime area after seeing police was sufficient for reasonable suspicion to stop and frisk.

The same requirement of founded suspicion for a “person” stop applies to stops of individual vehicles. United States v. Arvizu, 534 U.S. 266 (2002). The scope of the “frisk” for weapons during a vehicle stop may include areas of the vehicle in which a weapon may be placed or hidden. Michigan v. Long, 463 U.S. 1032 (1983). The police may order passengers and the driver out of or into the vehicle pending completion of the stop. Maryland v. Wilson, 519 U.S. 408 (1997). The passengers may not be detained longer than it takes the driver to receive his citation. Once the driver is ready to leave, the passengers must be permitted to go as well. During a stop for traffic violations, the officers need not independently have reasonable suspicion that criminal activity is afoot to justify frisking passengers, but they must have reason to believe the passengers are armed and dangerous. Arizona v. Johnson, 129 S Court. 781, 784 (2009).

The Difference Between the Two – The terms probable cause and reasonable suspicion are often confused and misused. While both have to do with a police officer’s overall impression of a situation, the two terms have different repercussions on a person’s rights, the proper protocol and the outcome of the situation.

Reasonable suspicion is a step before probable cause. At the point of reasonable suspicion, it appears that a crime may have been committed. The situation escalates to probable cause when it becomes obvious that a crime has most likely been committed.

Probable Cause to Search

In order to obtain a search warrant, the court must consider whether based on the totality of the information there is a fair probability that contraband, evidence or a person will be found in a particular place. Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213 (1983).

Probable Cause to Arrest

In order to arrest a suspect the officer must have a good faith belief that a crime has been committed and the individual he is arresting committed the crime. In Maryland v. Pringle, 540 U.S. 366 (2003). In Pringle, an officer was permitted to arrest three individuals in a vehicle where marijuana was discovered. The court reasoned that, even though the officers did not have evidence that any one of the three occupants was responsible for the drugs, probable cause existed as to all of them because co-occupants of a vehicle are often engaged in a common enterprise and all three denied knowing anything about the drugs.

Texas – Goldberg v. State, 95 SW.3d 345 (Tex. App. 2002).

An arrest is proper when it is based upon article 14.03 (a)(1) of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, which permits a peace officer to arrest a person without a warrant if the person is found in a suspicious place and under circumstances that reasonably show that such person has been guilty of some felony or breach of the peace.

Facts: Mr. Goldberg was accused of entering a wig store, punching one attendant in the throat, and cutting the other attendant’s wrist and stabbing her when she attempted to call for help. The assailant quickly left the store. A witness in the parking lot followed the assailant to his vehicle. The witness provided police with a license plate number for the vehicle. The police traced the vehicle and located the defendant, the son of the owner of the vehicle. The police handcuffed Mr. Goldberg, performed a pat down and informed him of his rights. Mr. Goldberg stated he was willing to talk to the officers. He was later uncuffed.

The officer felt the hood of the vehicle and it was still warm. Mr. Goldberg denied driving the vehicle or knowledge of the crime. The officers also noticed a blood stain on Mr. Goldberg’s shirt and a red mark on his chest. Goldberg consented to a search of the house, his apartment and the vehicle. The officers found fibers matching the wigs at the wig shop. Mr. Goldberg claimed that the vehicle had been stolen several times but the person always returned the vehicle to the residence. Mr. Goldberg was taken to the police station and consented to a police interrogation. He later was released to his mother. Mr. Goldberg challenged the arrest as unlawful.

The court found that even if the detention rose to the level of an arrest when the defendant was transported to the police station it was proper. Probable cause exists where the police have reasonably trustworthy information sufficient to warrant a reasonable person to believe a particular person has committed or is committing an offense. Guzman v. State, 955 SW.2d at 87; Amores v. State, 816 SW.2d 407, 413 (Tex. Crim. App.1991). Probable cause deals with probabilities; it requires more than mere suspicion but far less evidence than that needed to support a conviction or even that needed to support a finding by a preponderance of the evidence. Guzman, 955 SW.2d at 87. source

Principles of Probable Cause and Reasonable Suspicion

Although there is certainly more to probable cause and reasonable suspicion than just principles, it’s a good place to start, so that is where we will begin this four-part series. In part two, which begins on page 9, we will explain how officers can prove that the information they are relying upon to establish probable cause or reasonable suspicion was sufficiently reliable that is has significance. Then, in the Fall 2014 edition we will cover probable cause to arrest, including the various circumstances that officers and judges frequently consider in determining whether it exists. The series will conclude in the Winter 2015 edition with an discussion of how officers can determine whether they have probable cause to search.

It is ordinarily a bad idea to begin an article by admitting that the subjects to be discussed cannot be usefully defined. But when the subjects are probable cause and reasonable suspicion1, and when the readership is composed of people who have had some experience with them, it would be pointless to deny it. Consider that the Seventh Circuit once tried to provide a good legal definition but concluded that, when all is said and done, it just means having “a good reason to act.”2 Even the Supreme Court— whose many powers include defining legal terms— decided to pass on probable cause because, said the Court, it is “not a finely-tuned standard”3 and is actually an “elusive” and “somewhat abstract” concept.4 As for reasonable suspicion, the uncertainty is even worse. For instance, in United States v. Jones the First Circuit would only say that it “requires more than a naked hunch.”5

But this imprecision is actually a good thing because probable cause and reasonable suspicion are ultimately judgments based on common sense, not technical analysis. Granted, they are important judgments because they have serious repercussions. But they are fundamentally just rational assessments of the convincing force of information, which is something the human brain does all the time without consulting a rule book. So instead of being governed by a “neat set of rules,”6 these concepts mainly require that officers understand certain principles— principles that usually enable them to make these determinations with a fair degree of consistency and accuracy.

First, however, it is necessary to explain the basic difference between probable cause and reasonable suspicion, as these terms will be used throughout this series. Both are essentially judgments as to the existence and importance of evidence. But they differ as to the level of proof that is required. In particular, probable cause requires evidence of higher quality and quantity than reasonable suspicion because it permits officers to take actions that are more intrusive, such as arresting people and searching things. In contrast, reasonable suspicion is the standard for lesser intrusions, such as detentions and pat searches. As the Supreme Court explained:

Reasonable suspicion is a less demanding standard than probable cause not only in the sense that reasonable suspicion can be established with information that is different in quality or content than that required to establish probable cause, but also in the sense that reasonable suspicion can arise from information that is less reliable than that required to show probable cause.7

What Probability is Required?

When people start to learn about probable cause or reasonable suspicion, they usually want a number: What probability percentage is required?8 Is it 80%? 60%? 50%? Lower than 50? No one really knows, which might seem strange because, even in a relatively trivial venture such as sports betting, people would not participate unless they had some idea of the odds.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court has refused to assign a probability percentage to these concepts because it views them as nontechnical standards based on common sense, not mathematical precision.9 “The probable cause standard,” said the Court, “is incapable of precise definition or quantification into percentages because it deals with probabilities and depends on the totality of circumstances.”10 Similarly, the Tenth Circuit observed, “Besides the difficulty of agreeing on a single number, such an enterprise would, among other things, risk diminishing the role of judgment based on situation-sense.”11 Still, based on inklings from the United States Supreme Court, it is possible to provide at least a ballpark probability percentage for probable cause.

Reasonable suspicion, on the other hand, remains an enigma.

Probable cause

Many people assume that probable cause requires at least a 51% probability because anything less would not be “probable.” While this is technically true, the Supreme Court has ruled that, in the context of probable cause, the word “probable” has a somewhat different meaning. Specifically, it has said that probable cause requires neither a preponderance of the evidence nor “any showing that such belief be correct or more likely true than false,”12 and that it requires only a “fair” probability, not a statistical probability.13 Thus, it is apparent that probable cause requires something less than a 50% chance.14 How much less? Although no court has tried to figure it out, we suspect it is not much lower than 50%.

Reasonable suspicion

As noted, the required probability percentage for reasonable suspicion is a mystery. Although the Supreme Court has said that it requires “considerably less [proof] than preponderance of the evidence”15 (which means “considerably less” than a 50.1% chance), this is unhelpful because a meager 1% chance is “considerably less” than 51.1% but no one seriously thinks that would be enough. Equally unhelpful is the Supreme Court’s observation that, while probable cause requires a “fair probability,” reasonable suspicion requires only a “moderate” probability.16 What is the difference between a “moderate” and “fair” probability? Again, nobody knows. What we do know is that the facts need not rise to the level that they “rule out the possibility of innocent conduct.”17 As the Court of Appeal explained, “The possibility of an innocent explanation does not deprive the officer of the capacity to entertain a reasonable suspicion of criminal conduct. Indeed, the principal function of his investigation is to resolve that very ambiguity.”18 We also know that reasonable suspicion may exist if the circumstances were merely indicative of criminal activity. In fact, the California Supreme Court has said that if the circumstances are consistent with criminal activity, they “demand“ an investigation.”19

Basic Principles

Having given up on a mathematical solution to the problem, we must rely on certain basic principles. And the most basic principle is this: Neither probable cause nor reasonable suspicion can exist unless officers can cite “specific and articulable facts” that support their judgment.20 This demand for specificity is so important that the Supreme Court called it the “central teaching of this Court’s Fourth Amendment jurisprudence.” 21 The question, then, is this: How can officers determine whether their “specific and articulable” facts are sufficient to establish probable cause or reasonable suspicion? That is the question we will address in the remainder of this article.

Totality of the circumstances

Almost as central as the need for facts is the requirement that, in determining whether officers have probable cause and reasonable suspicion, the courts will consider the totality of circumstances. This is significant because it is exactly the opposite of how some courts did things many years ago. That is, they would utilize a “divide-and-conquer”22 approach which meant subjecting each fact to a meticulous evaluation, then frequently ruling that the officers lacked probable cause or reasonable suspicion because none of the individual facts were compelling. This practice officially ended in 1983 when, in the landmark decision in Illinois v. Gates, the Supreme Court announced that probable cause and reasonable suspicion must be based on an assessment of the convincing force of the officers’ information as a whole. “We must be mindful,” said the Fifth Circuit, “that probable cause is the sum total of layers of information and the synthesis of what the police have heard, what they know, and what they observed as trained officers. We weigh not individual layers but the laminated total.23 Thus, in People v. McFadin the court responded to the defendant’s “divide-and-conquer” strategy by utilizing the following analogy:

Defendant would apply the axiom that a chain is no stronger than its weakest link. Here, however, there are strands which have been spun into a rope. Although each alone may have insufficient strength, and some strands may be slightly frayed, the test is whether when spun together they will serve to carry the load of upholding [the probable cause determination].24

Here is an example of how the “totality of the circumstances” test works and why it is so important. In Maryland v. Pringle 25 an officer made a traffic stop on a car occupied by three men and, in the course of the stop, saw some things that caused him to suspect that the men were drug dealers. One of those things was a wad of cash ($763) that the officer had seen in the glove box. He then conducted a search of the vehicle and found cocaine. But a Maryland appellate court ruled the search was unlawful because the presence of money is “innocuous.” The Supreme Court reversed, saying the Maryland court’s “consideration of the money in isolation, rather than as a factor in the totality of the circumstances, is mistaken.”

Common sense

Not only did the Court in Gates rule that probable cause must be based on a consideration of the totality of circumstances, it ruled that the significance of the circumstances must be evaluated by applying common sense, not hypertechnical analysis. In other words, the circumstances must be “viewed from the standpoint of an objectively reasonable police officer.”26 As the Court explained:

Perhaps the central teaching of our decisions bearing on the probable cause standard is that it is a practical, nontechnical conception. In dealing with probable cause, as the very name implies, we deal with probabilities. These are not technical; they are the factual and practical considerations of everyday life on which reasonable and prudent men, not legal technicians, act.27

Legal, but suspicious, activities

It follows from the principles discussed so far that it is significant that officers saw the suspect do something that, while not illegal, was suspicious in light of other circumstances.28 As the Supreme Court explained, the distinction between criminal and noncriminal conduct “cannot rigidly control” because probable cause and reasonable suspicion “are fluid concepts that take their substantive content from the particular contexts in which they are being assessed.”29 For example, in Massachusetts v. Upton the state court ruled that probable cause could not have existed because the evidence “related to innocent, nonsuspicious conduct or related to an event that took place in public.” Acknowledging that no single piece of evidence was conclusive, the Supreme Court reversed, saying the “pieces fit neatly together.”30 Similarly, the Court of Appeal noted that seeing a man running down a street “is indistinguishable from the action of a citizen engaged in a program of physical fitness.” But it becomes “highly suspicious” when it is “viewed in context of immediately preceding gunshots.”31