In Vermont, someone who breaks the disorderly conduct law must have done something that is significantly physical, such as fighting or obstructing traffic.

The lower court ruled that because Schenk placed fliers in the door and in the mailbox of the women’s homes, he was intruding upon their privacy, which was considered to be a significant enough physical action and in part led to his earlier conviction. Griffin defended the lower court’s interpretation of disorderly conduct.

If any of the decisions the Vermont court decides is appealed, the case would go straight to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court can decide which cases it wants to hear, meaning if it decides not to take a Vermont case, the Vermont Supreme Court ruling would be final.

Decisions will be handed down by the justices as early as next month. source

Burlington KKK flier case conviction overturned by Vermont Supreme Court Vermont’s highest court has overturned the 2016 conviction of William Schenk, who prosecutors charged with hate crime-enhanced disorderly conduct for leaving Ku Klux Klan fliers at the houses of women of color in Burlington.

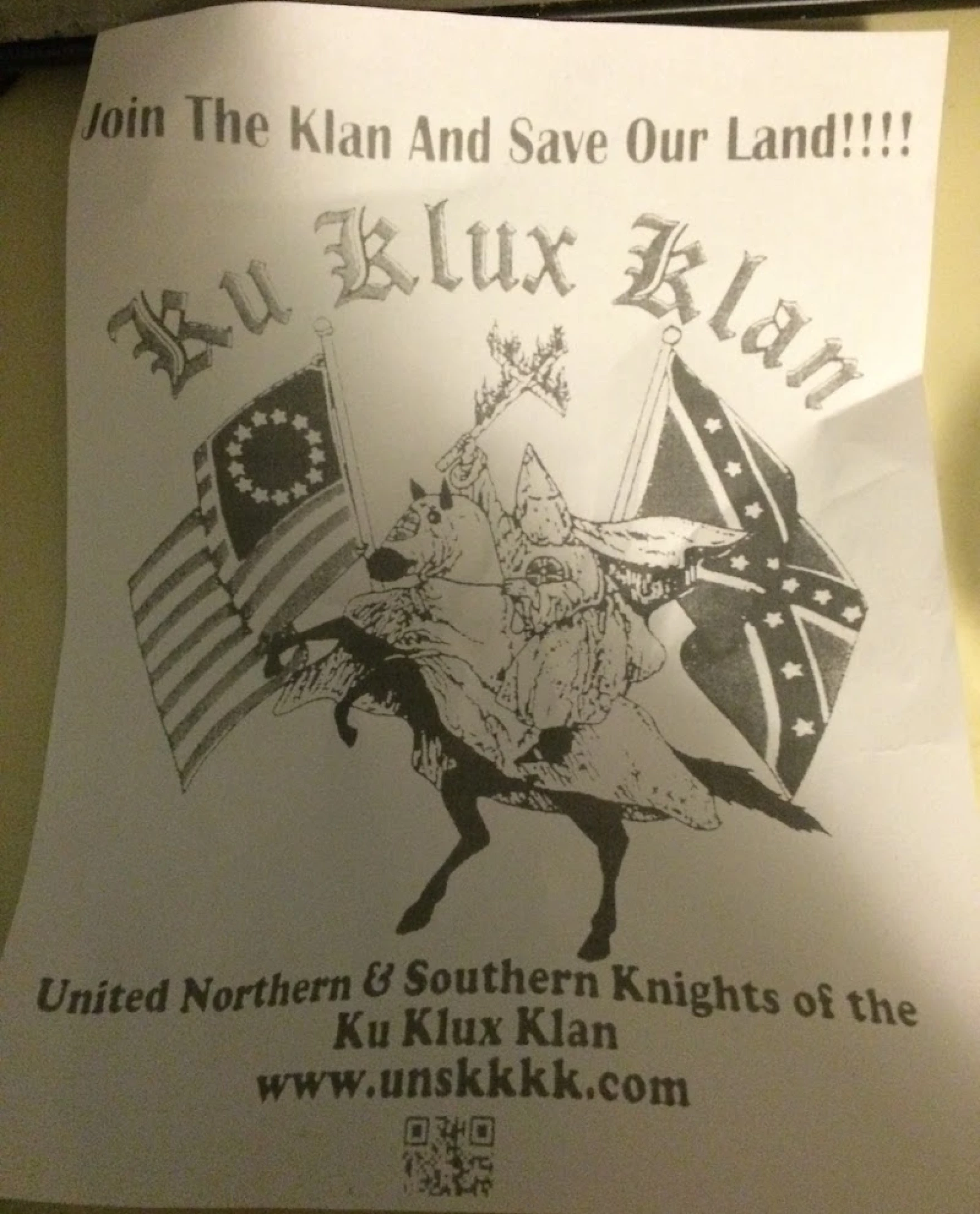

Schenk was sentenced to 120 days in jail for leaving recruitment fliers featuring a picture of a Klan member in robes holding a burning cross at the homes of two women of color in October 2015.

Schenk challenged the ruling, arguing the fliers are protected speech under the Constitution. Prosecutors had argued that he had deliberately targeted the women in an attempt to instill fear, and that his actions fell under the disorderly statute’s “threatening behavior” clause.

On Friday the state supreme court said Vermont’s disorderly conduct statute applies to conduct, not speech, and that leaving the fliers at the homes of the women constituted speech.

The court disagreed that leaving the fliers fell under “threatening behavior,” and added that the fliers also carried no imminent threat of harm.

The decision caused a split on the court.

Justice Beth Robinson offered a dissent, calling the majority’s interpretation of the term threatening behavior “excessively narrow.”

“But even though we do not today see the breadth and severity of the violence associated with the Klan of a prior era, the legacy of the Klan and the violence it represents is not a dead letter in today’s America,” she wrote, arguing that a drawing of a Klan member could reasonably be understood as a veiled threat. “The potency of the burning cross symbol, and the organization with which it is so closely associated, shapes the context of the communications in this case.”

The majority of the court declined to examine whether Schenk’s conduct included a “true threat,” and did not directly address the First Amendment issues raised.

“We do recognize that any communication from the Ku Klux Klan complete with symbols of the Klan, particularly the burning cross, would raise concern and fear in a reasonable person who is a member of an ethnic or racial minority,” the opinion states. “We are not ruling today whether the Legislature can make criminal such action or has done so in a different statute.”

Attorney General TJ Donovan, who prosecuted the case as state’s attorney, said he was disappointed in the court’s decision and believed in the case’s importance, but respected the court’s authority.

“In my opinion and view of this case, the delivery of the fliers was an act and implicit in that act was a threat directed at women of color,” Donovan said.

James Duff Lyall, the executive director of the American Civil Liberties of Vermont, said the court had ruled “rightly,” while condemning Schenk’s beliefs and acknowledging that the leaflets caused real fear.

“That speech, however, cannot be prosecuted as disorderly conduct,” Lyall said.

Schenk has already served the 120-day sentence. source

Challenging state’s criminalization of First Amendment protected leafletting activity as a “true threat” under an unconstitutional intent standard.

We filed an amicus brief in the Vermont Supreme Court in William Schenk’s appeal of his conviction for disorderly conduct arising from his placement of KKK recruitment leaflets in Burlington. While the ACLU does not represent Mr. Schenk and the amicus brief specifically describes the KKK as a “despicable hate group which advocates an abhorrent ideology of white supremacy,” our brief nonetheless advocates in favor of longstanding constitutional principles that extend First Amendment protections to inflammatory, vicious, and even hateful speech, as well as targeted leafletting.

While acknowledging that not all speech is entitled to First Amendment protection, including so-called “true threats,” our brief argues that Schenk’s case does not fall within that narrow exception. The brief cites to Virginia v. Black , a 2003 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional to prosecute someone for cross-burning absent clear evidence of intent to threaten. We argue that the same principle articulated by the Supreme Court in Black applies to the Schenk case—the state has to prove its case, especially when speech is concerned, and cannot punish speech based on its content. source

The Vermont Supreme Court overturned the conviction of a man who left KKK recruitment flyers at the Burlington homes of two women of color. The court said the state failed to prove the action constituted an immediate threat. Free Speech Or A Threat? Vermont Supreme Court Decision Highlights Continuing Tension

Last week, the court overturned the conviction of a man who put Ku Klux Klan flyers on the Burlington homes of two women of color. The court said the state didn’t prove the action met the threshold of ‘threatening behavior.’

The decision highlights the on-going tension around protecting speech even when it’s potentially threatening or hateful. In 2015, two women found KKK flyers at their homes . None of their neighbors had gotten them.

The flyers show a robed Klansman, holding a burning cross and the phrase “join the Klan and save our land.”

Police arrested and charged William Schenk with two counts of disorderly conduct. He pleaded guilty, but the supreme court later overturned his conviction .

Their decision doesn’t sit right with Jabari Jones, a spokesperson for Black Lives Matter of Greater Burlington .

“Do they have to tie the note to a rock and throw it through their window and then throw a Molotov cocktail?” Jones said. “Like, how obvious does the threat have to be to be taken seriously? Particularly it seems if it’s threats against people of color.”

In its decision, the court said prosecutors didn’t prove that Schenk’s actions went far under Vermont’s disorderly conduct statue to be threat.

Jared Carter, an assistant professor at Vermont Law School, said the state had to prove that Schenk’s actions — leaving the flyers — constituted an immediate threat to the two women.

“And that since the activities here were primarily speech — the delivery of some fliers, heinous fliers but speech nonetheless — the state, as a matter of fact, and a matter of law could not meet its burden of proof,” Carter said.

” Like, how obvious does the threat have to be to be taken seriously — particularly it seems if it’s threats against people of color.” — Jabari Jones, Black Lives Matter of Greater Burlington

The state argued, given the KKK’s history of violence and because the individuals who got the fliers were people of color, Schenk’s conviction should stand.

VPR couldn’t reach the two women who received the fliers, but according to court records, both said the incident scared them.

One said based on the history of the KKK she feared for her safety.

Jones with Black Lives Matter of Greater Burlington said the court’s decision ignores the KKK’s extensive history of violence and intimidation.

“If we can’t look at white supremacist terrorist speech in that context then what we’re doing is actually reinforcing and upholding white supremacist violence,” Jones said.

But the American Civil Liberties Union of Vermont says it’s a matter of protecting all free speech.

Staff attorney Jay Diaz said in this case, the speech isn’t a threat.

“When you have a hate group doing things like this and people are afraid how do we reconcile that with our long standing traditions of free political speech,” Diaz said.

“We want to be careful not to allow the criminalization of speech that gets to political issues … We want to be very careful with that because the First Amendment, in the end, protects everybody.” — Jay Diaz, ACLU of Vermont

The group filed a brief supporting the dismissal of Schenk’s charges .

Diaz said the KKK is a hate organization and the ACLU condemns its actions.

“However, we want to be careful not to allow the criminalization of speech that gets to political issues,” Diaz said. “Our country has a long history of criminalizing political speech for organizations that we support such as the NAACP and many others. So we want to be very careful with that … because the First Amendment, in the end, protects everybody.”

Protecting free speech and protecting individuals is a difficult for courts, according to Carter, the law professor.

“The Vermont Supreme Court has decided to deal with this case on simply interpreting the statute rather than reaching these bigger questions of how far can we limit speech, is this particular activity by Mr. Schenk constitutionally protected or not,” Carter said.

Carter said the court left those bigger questions for another day.

Disclosure: Jared Carter is an occasional VPR commentator. source

State’s top court tosses convictions in KKK flier case [A] North Carolina man accused of targeting two women of color with Ku Klux Klan recruitment fliers has had his convictions for disorderly conduct tossed out by the Vermont Supreme Court.

In a 3-2 decision issued Friday, a majority of the state’s high court ruled in favor of William Schenk, who was 21 at the time of his arrest on the charges three years ago.

Police say he posted fliers depicting a hooded Klan member on horseback holding a burning cross, with the words “Join the Klan, Save our Land” — at two women’s apartments in Burlington’s South End neighborhood in October 2015.

“The flyer (sic) is a recruitment solicitation — its overt message is to join the Ku Klux Klan. It contains no explicit statement of threat,” the majority opinion from the high court read.

“To the extent it conveys a message of personal threat to the recipient, it is that the Klan will recruit members and inflict harm in the future,” the decision stated. “The flyer itself is not ‘immediately likely to produce’ force and harm.”

Schenk, who was living and working in Burlington, told police he delivered as many as 50 of the fliers in the Burlington neighborhood.

However, according to police, the two women of color, one identified in court records as African-American and the other as Mexican, are the only people known to have received them.

Schenk pleaded no contest in April 2016 to the two misdemeanor counts of disorderly conduct enhanced by a hate crime penalty. He was sentenced to four months in jail on each charge, to be served concurrently.

In pleading no contest, Schenk had to acknowledge, but not agree to, the facts prosecutors put forward in the case; he also acknowledged that they could be proven beyond a reasonable doubt. The facts included that he acted recklessly and threateningly toward the women and that he was maliciously motivated by their race.

His plea was conditioned on reserving his right to appeal to the Vermont Supreme Court.

The three justices ruling in Schenk’s favor were Harold Eaton, Marilyn Skoglund and John Dooley, who has since hearing arguments in the case in 2017 retired from the court.

Chief Justice Paul Reiber and Justice Beth Robinson joined in a dissenting opinion.

According to the dissenting opinion, taking the evidence “in the light most favorable” to the prosecution, a reasonable jury could conclude that Schenk’s communications amounted to “threatening behavior.”

“The singling out of these particular minority victims for receipt of the flyers,” the dissenting opinion read, “the history of the Ku Klux Klan and the imagery of hooded Klansmen and burning crosses, and the anonymous and intrusive placement of the flyers in the doors of the victims’ homes are three critical factors that, in combination, support this conclusion.”

Vermont Defender General Matthew Valerio, whose office represented Schenk, said Friday that while the “activity that went on at the time was distasteful,” it wasn’t a crime.

“The Supreme Court never even had to reach the idea of whether or not it was First Amendment activity,” Valerio said. “The fact that what he did didn’t add up to anything that was threatening is what gave rise to the Supreme Court saying that there wasn’t probable cause” for the charges.

Vermont Attorney General TJ Donovan, who was the Chittenden County state’s attorney at the time of Schenk’s prosecution, said Friday that he was disappointed by the high court’s ruling.

“My opinion was that the physical delivery of the fliers, the pamphlets, was the act and implicit in that act was the threat,” he said.

“If you asked anybody who is a person of color, they received a flier from the KKK directed at them, that is an implicit threat because the KKK is a hate group directed toward people of color,” Donovan said. “That’s why we filed the charge, that’s why I’m disappointed, but at end of the day I respect the Supreme Court’s authority and their decision.”

The Vermont chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union filed a “friend of the court brief” in the appeal of the case before the Supreme Court. The ACLU argued that prosecutors didn’t produce evidence that Schenk intended the leaflets as a “true threat,” and that without that evidence, political leafletting is protected speech.

James Lyall, the ACLU of Vermont’s executive director, issued a statement Friday saying that while Schenk’s conduct was “reprehensible and fully deserving of the public condemnation it received,” he supported the decision.

“The Court’s ruling does not directly address the difficult First Amendment issues in this case, but rather holds that the facts of the case did not support a charge of disorderly conduct. We agree,” Lyall added. “The Court rightly acknowledges that Mr. Schenk’s delivery of racist leaflets caused their recipients real fear. That speech, however, cannot be prosecuted as disorderly conduct.”The ruling, he said, leaves unresolved whether similar conduct could be prosecuted in the future, including under a criminal threatening statute that was enacted into law in 2016, after Schenk’s arrest. source