WHAT ARE THE “MIRANDA RIGHTS?”

The Miranda Rights derive their name from the Supreme Court Case Miranda v. Arizona. This established the requirement of police to “read you your rights” after an arrest and before questioning you. In this landmark case, the court decided that the constitutional rights of Ernesto Miranda were violated during his arrest and trial for armed robbery, kidnapping, and rape. Put simply, the law requires law enforcement officers to explain your Miranda rights after your arrest, but before questioning you, or pursuing a formal statement while in police custody. However, the rights themselves are simply a restating of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the Constitution—namely, the right not to incriminate yourself and the right to have an attorney.

The Miranda Rights derive their name from the Supreme Court Case Miranda v. Arizona. This established the requirement of police to “read you your rights” after an arrest and before questioning you. In this landmark case, the court decided that the constitutional rights of Ernesto Miranda were violated during his arrest and trial for armed robbery, kidnapping, and rape. Put simply, the law requires law enforcement officers to explain your Miranda rights after your arrest, but before questioning you, or pursuing a formal statement while in police custody. However, the rights themselves are simply a restating of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the Constitution—namely, the right not to incriminate yourself and the right to have an attorney.

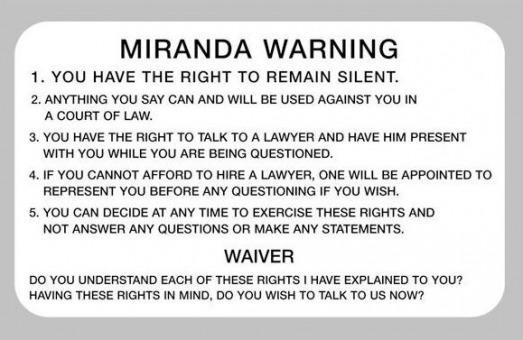

By law, after you’ve been arrested, the police officer must make some version of the below statement, known as the Miranda Warning, before asking you any questions:

“You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford a lawyer, one will be provided for you. Do you understand the rights I have just read to you? With these rights in mind, do you wish to speak to me?”

As noted above, the police must read you the Miranda Warning after you have been arrested and before interrogating you.

If they fail to read you this warning before asking you questions, any evidence they obtain in their conversations with you may be inadmissible in court.

basically this law is when they DO NOT READ YOU YOUR RIGHTS AND THEN INTERROGATE YOU, IF THEY ASK YOU SOMETHING MOUTH CLOSED, IF YOU SNITCH ON YOURSELF ON THE WAY TO THE STATION YOU FUCKED YOURSELF!

DO THE POLICE HAVE TO READ THE MIRANDA WARNING AT THE TIME OF YOUR ARREST?

Not necessarily—and this is where some people get confused. Your Miranda Rights have nothing to do with the arrest itself—only with police questioning you after your arrest.

They only have to make sure your rights have been explained to you before they interrogate you.

If they opt not to ask you any questions, they’re not legally required to read you your rights at all. Conversely, if you’re not under arrest, they can still ask you anything they like without reading the warning, but you don’t have to answer.

MIRANDA WARNINGS IN DUI CASES

Police officers are normally not required to read Miranda rights during a DUI investigation after a traffic stop unless you were placed under arrest and they start asking incriminating questions.

Put simply, a Miranda warning is not always required after a driving under the influence arrest. It only be read if you were already arrested and then you are being interrogated.

If law enforcement is conducting a DUI investigation on the side of the road, before any arrest are made, it’s a myth you must be read Miranda rights.

During a DUI investigation, police officers will normally follow certain procedures, such as:

- Ask the driver for a driver’s license and proof of insurance;

- Ask the driver to perform field sobriety tests and also a preliminary alcohol screening (PAS) breath test;

- Ask the driver to take a cheek swab to test for marijuana DUI;

- Ask the driver to submit to a horizontal nystagmus test (HGN), which is an involuntary jerking of the eyes;

- During these initial questions, they are looking for signs such as breath smelling of alcohol, slurred speech, watery eyes, incoherent speech, slow and confused responses, poor motor skills, difficulty in removing driver’s license from wallet, etc.

They will also ask common questions such as if you were drinking or have you taken any drugs today?

As you can see, during this DUI investigation, you have not yet been arrested and there is no legal requirement to read your rights during this process.

If you are subsequently arrested for DUI after the investigation, then the Miranda warning is required before asking any further incriminating questions.

Readers should note that during a DUI traffic stop, you always have the right to remain silent and not speak at all to police officers.

Put simply, you don’t have to answer any of their questions after the traffic stop and during the DUI investigation. This does not mean it’s wise to be a jerk and completely uncooperative.

However, you are required to show them your driver’s license and proof of insurance.

CAN MIRANDA BE WAIVED?

Yes. after you are read the Miranda warning, police will normally ask if you understand each right.

Next, they will ask you if you still want to speak to them? This is commonly called a “Miranda waiver.”

Police officers are not legally required to use certain words when asking if you wish to waive your Miranda rights. Most will ask some form of these questions below:

- Do you clearly understand all of these rights I just explained?

- Knowing you have the right to remain silent and not answer any questions, will you talk to us?

If you verbally agree to speak with them at this point, then you have just waived your Miranda rights and invoked the right to remain silent.

You might be asked to sign a written waiver acknowledging that you have waived your rights.

I WAS NEVER READ MY RIGHTS. CAN THE POLICE STILL USE WHAT I SAY AGAINST ME?

Possibly. This part is, again, confusing for some. Remember, the police only have to read the Miranda Warning before they begin to question you.

However, the second statement of that warning, “anything you say can be used against you,” still applies.

If you say something voluntarily before they start questioning you—or if they never officially question you—the words you said in their presence may still be used against you in court.

That’s why it’s always best to remain silent until speaking with an attorney—whether or not your rights are read to you.

If, however, the police do start questioning you without reading the Miranda Warning first, that’s considered a violation of your rights, and what you say beyond that point may not be used as evidence against you.

WHAT HAPPENS IF YOUR RIGHTS ARE VIOLATED?

In review, the following may be considered a violation of your Miranda Rights:

- If the police interrogate you without reading you the Miranda Warning;

- If they do not permit you to have an attorney present while questioning you; or

- If they attempt to coerce you into making self-incriminating statements during the interrogation;

- Law enforcement officers failed to give any warning.

In these cases, the answers you give should be inadmissible in court.

At that point, your attorney will usually file a “motion to suppress evidence,” claiming that the statements you made to the police under those circumstances were obtained illegally. If the court agrees, those statements will be thrown out.

WILL YOUR CASE BE DISMISSED OVER MIRANDA VIOLATIONS?

Sometimes, but not always. A Miranda violation is not necessarily grounds for dismissing the charges against you.

It only means the information the police obtained during that violation, including any confession you may have made, was obtained involuntarily and may be used as evidence.

If the only evidence against you is evidence obtained illegally, then the case may be dismissed.

However, if the prosecution has additional evidence to prove their case against you, the case may still move forward.

We defend individuals charged with California crimes whenever their legal rights have been violated during or after an arrest.

When the government doesn’t inform you of your rights and then illegally obtains evidence or a confession, that evidence or confession could then be excluded in court, which is known as inadmissible evidence.

HERE IS THE COURT CASE THAT PROMPTED ALL THIS BELOW

U.S. Supreme Court

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966)

Miranda v. Arizona

No. 759

Argued February 28-March 1, 1966

Decided June 13, 1966*

384 U.S. 436

Syllabus

In each of these cases, the defendant, while in police custody, was questioned by police officers, detectives, or a prosecuting attorney in a room in which he was cut off from the outside world. None of the defendants was given a full and effective warning of his rights at the outset of the interrogation process. In all four cases, the questioning elicited oral admissions, and, in three of them, signed statements as well, which were admitted at their trials. All defendants were convicted, and all convictions, except in No. 584, were affirmed on appeal.

Held:

1. The prosecution may not use statements, whether exculpatory or inculpatory, stemming from questioning initiated by law enforcement officers after a person has been taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way, unless it demonstrates the use of procedural safeguards effective to secure the Fifth Amendment’s privilege against self-incrimination. Pp. 444-491.

(a) The atmosphere and environment of incommunicado interrogation as it exists today is inherently intimidating, and works to undermine the privilege against self-incrimination. Unless adequate preventive measures are taken to dispel the compulsion inherent in custodial surroundings, no statement obtained from the defendant can truly be the product of his free choice. Pp. 445-458.

(b) The privilege against self-incrimination, which has had a long and expansive historical development, is the essential mainstay of our adversary system, and guarantees to the individual the “right to remain silent unless he chooses to speak in the unfettered exercise of his own will,” during a period of custodial interrogation

as well as in the courts or during the course of other official investigations. Pp. 458-465.

(c) The decision in Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U. S. 478, stressed the need for protective devices to make the process of police interrogation conform to the dictates of the privilege. Pp. 465-466.

(d) In the absence of other effective measures, the following procedures to safeguard the Fifth Amendment privilege must be observed: the person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent, and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him. Pp. 467-473.

(e) If the individual indicates, prior to or during questioning, that he wishes to remain silent, the interrogation must cease; if he states that he wants an attorney, the questioning must cease until an attorney is present. Pp. 473-474.

(f) Where an interrogation is conducted without the presence of an attorney and a statement is taken, a heavy burden rests on the Government to demonstrate that the defendant knowingly and intelligently waived his right to counsel. P. 475.

(g) Where the individual answers some questions during in-custody interrogation, he has not waived his privilege, and may invoke his right to remain silent thereafter. Pp. 475-476.

(h) The warnings required and the waiver needed are, in the absence of a fully effective equivalent, prerequisites to the admissibility of any statement, inculpatory or exculpatory, made by a defendant. Pp. 476-477.

2. The limitations on the interrogation process required for the protection of the individual’s constitutional rights should not cause an undue interference with a proper system of law enforcement, as demonstrated by the procedures of the FBI and the safeguards afforded in other jurisdictions. Pp. 479-491.

3. In each of these cases, the statements were obtained under circumstances that did not meet constitutional standards for protection of the privilege against self-incrimination. Pp. 491-499.

98 Ariz. 18, 401 P.2d 721; 15 N.Y.2d 970, 207 N.E.2d 527; 16 N.Y.2d 614, 209 N.E.2d 110; 342 F.2d 684, reversed; 62 Cal. 2d 571, 400 P.2d 97, affirmed.

CITED FROM https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/384/436/