Humans Were Actually Apex Predators For 2 Million Years, Evidence Shows

By Mike Mcrae source

Paleolithic cuisine was anything but lean and green, according to a 2021 study on the diets of our Pleistocene ancestors. For a good 2 million years, Homo sapiens and their ancestors ditched the salad and dined heavily on meat, putting them at the top of the food chain.

It’s not quite the balanced diet of berries, grains, and steak we might picture when we think of ‘paleo’ food. But according to anthropologists from Israel’s Tel Aviv University and the University of Minho in Portugal, modern hunter-gatherers have given us the wrong impression of what we once ate.

“This comparison is futile, however, because 2 million years ago hunter-gatherer societies could hunt and consume elephants and other large animals – while today’s hunter gatherers do not have access to such bounty,” said Miki Ben‐Dor from Israel’s Tel Aviv University in April last year.

A look through hundreds of previous studies on everything from modern human anatomy and physiology to measures of the isotopes inside ancient human bones and teeth suggests we were primarily apex predators until roughly 12,000 years ago.

Reconstructing the grocery list of hominids who lived as far back as 2.5 million years ago is made all that much more difficult by the fact plant remains don’t preserve as easily as animal bones, teeth, and shells.

We can find ample evidence of game-hunting in the fossil record, but to determine what we gathered, anthropologists have traditionally turned to modern-day ethnography based on the assumption that little has changed.

According to Ben-Dor and his colleagues, this is a huge mistake.

“The entire ecosystem has changed, and conditions cannot be compared,” said Ben‐Dor.

The Pleistocene epoch was a defining time in Earth’s history for us humans. By the end of it, we were marching our way into the far corners of the globe, outliving every other hominid on our branch of the family tree.

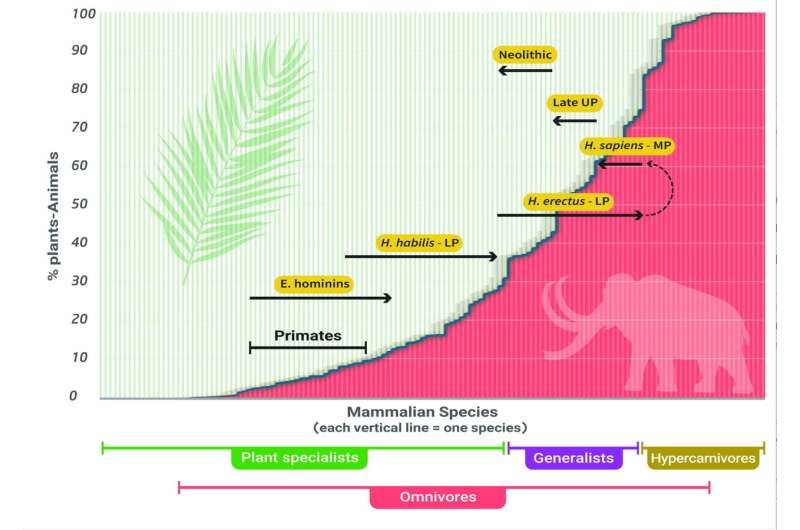

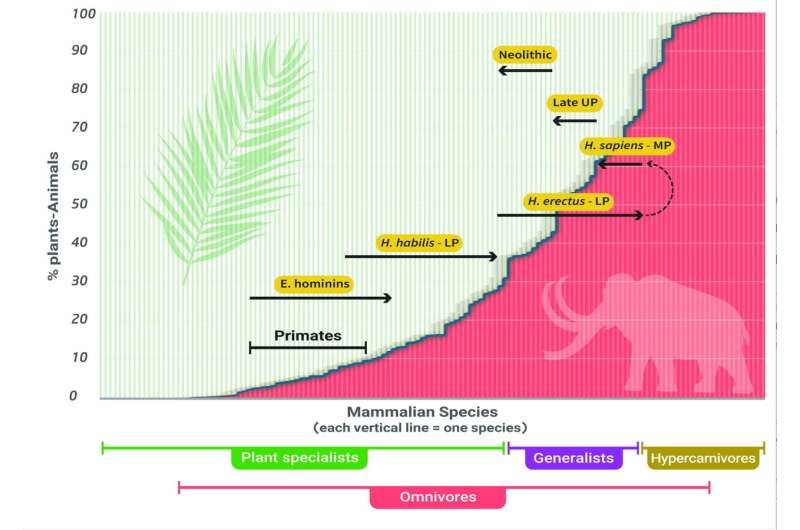

Above: Graph showing where Homo sapiens sat on the spectrum of carnivore to herbivore during the Pleistocene and Upper Pleistocene (UP).

Dominated by the last great ice age, most of what is today Europe and North America was regularly buried under thick glaciers.

With so much water locked up as ice, ecosystems around the world were vastly different to what we see today. Large beasts roamed the landscape, including mammoths, mastodons, and giant sloths – in far greater numbers than we see today.

Of course it’s no secret that Homo sapiens used their ingenuity and uncanny endurance to hunt down these massive meal-tickets. But the frequency with which they preyed on these herbivores hasn’t been so easy to figure out.

Rather than rely solely on the fossil record, or make tenuous comparisons with pre-agricultural cultures, the researchers turned to the evidence embedded in our own bodies and compared it with our closest cousins.

“We decided to use other methods to reconstruct the diet of stone-age humans: to examine the memory preserved in our own bodies, our metabolism, genetics and physical build,” said Ben‐Dor.

“Human behavior changes rapidly, but evolution is slow. The body remembers.”

For example, compared with other primates, our bodies need more energy per unit of body mass. Especially when it comes to our energy-hungry brains. Our social time, such as when it comes to raising children, also limits the amount of time we can spend looking for food.

We have higher fat reserves, and can make use of them by rapidly turning fats into ketones when the need arises. Unlike other omnivores, where fat cells are few but large, ours are small and numerous, echoing those of a predator.

Our digestive systems are also suspiciously like that of animals higher up the food chain. Having unusually strong stomach acid is just the thing we might need for breaking down proteins and killing harmful bacteria you’d expect to find on a week-old mammoth chop.

Even our genomes point to a heavier reliance on a meat-rich diet than a sugar-rich one.

“For example, geneticists have concluded that areas of the human genome were closed off to enable a fat-rich diet, while in chimpanzees, areas of the genome were opened to enable a sugar-rich diet,” said Ben‐Dor.

The team’s argument is extensive, touching upon evidence in tool use, signs of trace elements and nitrogen isotopes in Paleolithic remains, and dental wear.

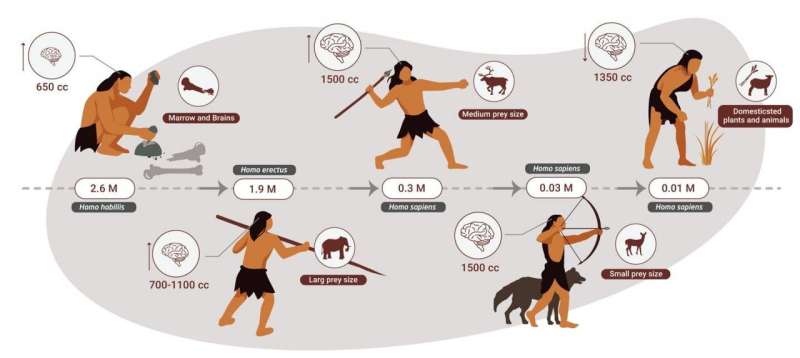

It all tells a story where our genus’ trophic level – Homo’s position in the food web – became highly carnivorous for us and our cousins, Homo erectus, roughly 2.5 million years ago, and remained that way until the upper Paleolithic around 11,700 years ago.

From there, studies on modern hunter-gatherer communities become a little more useful, as a decline in populations of large animals and fragmentation of cultures around the world saw to more plant consumption, culminating in the Neolithic revolution of farming and agriculture.

None of this is to say we ought to eat more meat. Our evolutionary past isn’t an instruction guide on human health, and as the researchers emphasize, our world isn’t what it used to be.

But knowing where our ancestors sat in the food web has a big impact on understanding everything from our own health and physiology, to our influence over the environment in times gone by.

Ancient Humans: The Real Apex Predators for a Good 2 Million Years

(Photo : Photo by CRIS BOURONCLE/AFP via Getty Images)

Prehistoric cuisine was far from lean and green. They are now at the apex of the food chain.

2 Million-Year Cuisine

According to a study of our Pleistocene ancestors’ diets, Prehistoric cuisine wasn’t exactly lean and green.

For nearly 2 million years, Homo sapiens as well as their predecessors eschewed salad in favor of a diet heavy on meat, propelling them to the top of the food chain. It’s not the good diet of fruits, grains, and steak that we might imagine once we imagine of ‘vegan’ food.

According to a study published last year by archaeologists from Israel’s Tel Aviv University and Portugal’s University of Minho, present hunter-gatherers had already granted us the false impression of what we decided to eat.

“This contrast is futile, however, seeing as hunter-gatherer communities could hunt and ingest animals and other large mammals 2 million years ago – while today’s cavemen do not have direct exposure to such bounty,” Tel Aviv University researcher Miki BenDor explained in 2021.

A review of hundreds of previous research ranging from contemporary anatomy and physiology of humans to isotope measurements in primitive human bones and teeth suggests that we were mainly apex predators until about 12,000 years ago.

Plant remains do not preserve as well as bone fragments, teeth, and shells, making reassembling the shopping list of early humans who lived 2.5 million years ago more difficult.

In Science Alert research findings have used chemical tests of bone fragments and tooth enamel to identify localized examples of plant-rich diets. But trying to extrapolate this to civilization is indeed more difficult.

There is plenty of proof of game hunting in the geological record, but anthropologists have traditionally relied on modern-day ethnography to determine what we gathered, assuming that little has changed.

Ancient Humans were Apex Predators

For humans, the Pleistocene era was a watershed moment in Earth’s history. We were progressing our way through the far reaches of the globe by the end, outlasting every other life form on our family tree’s branch tree. The last great ice age dominated most of what is now Europe and North America, burying it under thick glaciers on a regular basis. Given the amount of water stuck as ice, ecological systems all around world looked very different than they do now. Large beasts, such as woolly mammoth, mastodons, and giant sloths, roamed the landscape in the far increasing quantities than we see today.

It goes without saying that Homo sapiens were using their innovation and inexplicable endurance to track down such massive meal-tickets. However, determining the occurrence in which they relied on these plant eaters has proven difficult.

Rather than relying solely on the fossil evidence or making speculative comparability with which was before cultures, the researchers looked to the proof integrated in our own cells and compared it to that of our closest relatives.

We made the decision to use other methodologies to reconstruct stone-age human diets: to investigate the recollection retained in our own cells, our metabolism, genetics, and physical build, as stated by BenDor.

Humans were apex predators for two million years

Researchers at Tel Aviv University were able to reconstruct the nutrition of stone age humans. In a paper published in the Yearbook of the American Physical Anthropology Association, Dr. Miki Ben-Dor and Prof. Ran Barkai of the Jacob M. Alkov Department of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University, together with Raphael Sirtoli of Portugal, show that humans were an apex predator for about two million years. Only the extinction of larger animals (megafauna) in various parts of the world, and the decline of animal food sources toward the end of the stone age, led humans to gradually increase the vegetable element in their nutrition, until finally they had no choice but to domesticate both plants and animals—and became farmers.

“So far, attempts to reconstruct the diet of stone-age humans were mostly based on comparisons to 20th century hunter-gatherer societies,” explains Dr. Ben-Dor. “This comparison is futile, however, because two million years ago hunter-gatherer societies could hunt and consume elephants and other large animals—while today’s hunter gatherers do not have access to such bounty. The entire ecosystem has changed, and conditions cannot be compared. We decided to use other methods to reconstruct the diet of stone-age humans: to examine the memory preserved in our own bodies, our metabolism, genetics and physical build. Human behavior changes rapidly, but evolution is slow. The body remembers.”

In a process unprecedented in its extent, Dr. Ben-Dor and his colleagues collected about 25 lines of evidence from about 400 scientific papers from different scientific disciplines, dealing with the focal question: Were stone-age humans specialized carnivores or were they generalist omnivores? Most evidence was found in research on current biology, namely genetics, metabolism, physiology and morphology.

“One prominent example is the acidity of the human stomach,” says Dr. Ben-Dor. “The acidity in our stomach is high when compared to omnivores and even to other predators. Producing and maintaining strong acidity require large amounts of energy, and its existence is evidence for consuming animal products. Strong acidity provides protection from harmful bacteria found in meat, and prehistoric humans, hunting large animals whose meat sufficed for days or even weeks, often consumed old meat containing large quantities of bacteria, and thus needed to maintain a high level of acidity. Another indication of being predators is the structure of the fat cells in our bodies. In the bodies of omnivores, fat is stored in a relatively small number of large fat cells, while in predators, including humans, it’s the other way around: we have a much larger number of smaller fat cells. Significant evidence for the evolution of humans as predators has also been found in our genome. For example, geneticists have concluded that “areas of the human genome were closed off to enable a fat-rich diet, while in chimpanzees, areas of the genome were opened to enable a sugar-rich diet.”

Evidence from human biology was supplemented by archaeological evidence. For instance, research on stable isotopes in the bones of prehistoric humans, as well as hunting practices unique to humans, show that humans specialized in hunting large and medium-sized animals with high fat content. Comparing humans to large social predators of today, all of whom hunt large animals and obtain more than 70% of their energy from animal sources, reinforced the conclusion that humans specialized in hunting large animals and were in fact hypercarnivores.

“Hunting large animals is not an afternoon hobby,” says Dr. Ben-Dor. “It requires a great deal of knowledge, and lions and hyenas attain these abilities after long years of learning. Clearly, the remains of large animals found in countless archaeological sites are the result of humans’ high expertise as hunters of large animals. Many researchers who study the extinction of the large animals agree that hunting by humans played a major role in this extinction—and there is no better proof of humans’ specialization in hunting large animals. Most probably, like in current-day predators, hunting itself was a focal human activity throughout most of human evolution. Other archaeological evidence—like the fact that specialized tools for obtaining and processing vegetable foods only appeared in the later stages of human evolution—also supports the centrality of large animals in the human diet, throughout most of human history.”

The multidisciplinary reconstruction conducted by TAU researchers for almost a decade proposes a complete change of paradigm in the understanding of human evolution. Contrary to the widespread hypothesis that humans owe their evolution and survival to their dietary flexibility, which allowed them to combine the hunting of animals with vegetable foods, the picture emerging here is of humans evolving mostly as predators of large animals.

“Archaeological evidence does not overlook the fact that stone-age humans also consumed plants,” adds Dr. Ben-Dor. “But according to the findings of this study plants only became a major component of the human diet toward the end of the era.”

Evidence of genetic changes and the appearance of unique stone tools for processing plants led the researchers to conclude that, starting about 85,000 years ago in Africa, and about 40,000 years ago in Europe and Asia, a gradual rise occurred in the consumption of plant foods as well as dietary diversity—in accordance with varying ecological conditions. This rise was accompanied by an increase in the local uniqueness of the stone tool culture, which is similar to the diversity of material cultures in 20th-century hunter-gatherer societies. In contrast, during the two million years when, according to the researchers, humans were apex predators, long periods of similarity and continuity were observed in stone tools, regardless of local ecological conditions.

“Our study addresses a very great current controversy—both scientific and non-scientific,” says Prof. Barkai. “For many people today, the Paleolithic diet is a critical issue, not only with regard to the past, but also concerning the present and future. It is hard to convince a devout vegetarian that his/her ancestors were not vegetarians, and people tend to confuse personal beliefs with scientific reality. Our study is both multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary. We propose a picture that is unprecedented in its inclusiveness and breadth, which clearly shows that humans were initially apex predators, who specialized in hunting large animals. As Darwin discovered, the adaptation of species to obtaining and digesting their food is the main source of evolutionary changes, and thus the claim that humans were apex predators throughout most of their development may provide a broad basis for fundamental insights on the biological and cultural evolution of humans.”

More information: Miki Ben‐Dor et al, The evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene, American Journal of Physical Anthropology (2021). DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.24247

Journal information: American Journal of Physical Anthropology

Provided by Tel-Aviv University