Actual Malice

Actual malice is the legal standard established by the Supreme Court for libel cases to determine when public officials or public figures may

recover damages in lawsuits against the news media.

Public officials cannot win libel cases without proof of actual malice

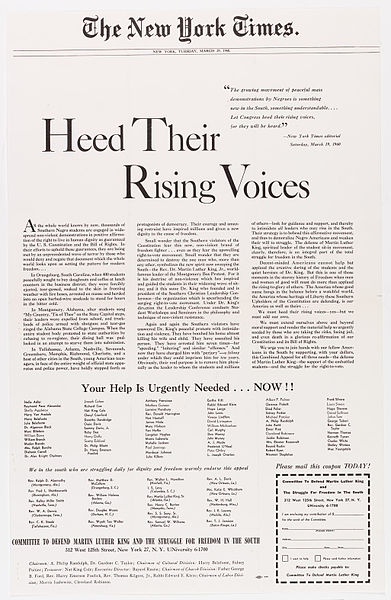

Beginning with the unanimous decision in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Supreme Court has held that public officials cannot recover damages for libel without proving that a statement was made with actual malice — defined as “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

The decision in Sullivan threw out a damage award against the New York Times, but only six of the nine justices fully agreed with Justice William J. Brennan Jr.’s use of the actual malice standard, which he derived from a Kansas Supreme Court ruling, Coleman v. MacLennan (Kan. 1908). Justices Hugo L. Black and Arthur J. Goldberg, joined by Justice William O. Douglas, thought the Court should go farther to protect criticism of public officials and debate about public affairs.

Public figures, officials bear burden of proving actual malice

In subsequent cases, the Supreme Court elaborated on the actual malice test in the libel context. In St. Amant v. Thompson (1968), the Court recognized the standard as a subjective one, requiring proof that the defendant actually had doubts about the truth or falsity of a story. It extended the application of the actual malice test to public figures, not just public officials, in Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts (1967).

Under the actual malice standard, if the individual who sues is a public official or public figure, that individual bears the burden of proving that the media defendant acted with actual malice. The amount of proof must be “clear and convincing evidence,” and the standard applies to compensatory as well as to punitive damages.

Actual malice not required for private figures

Concerning private figures, however, the Court ruled in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974) that actual malice is not required for recovery of compensatory damages, but is the standard for punitive damages.

Court has used actual malice test to give news First Amendment protection

The Supreme Court has expanded the reach of the First Amendment to afford the news media protection against other types of lawsuits designed to protect individual privacy, including those alleging intentional infliction of emotional distress, as in Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988); disclosure of private facts, as per Florida Star v. B.J.F. (1989); and depicting someone in a false light, as in Time Inc. v. Hill (1967). In all of these cases, the Court applied the same actual malice test to further recognize the principle of free and open comment in a democratic society.

The actual malice standard has at times drawn criticism from people in the public eye who think the test makes it too hard for them to restore their reputations and from the news media, which has complained that the standard does not afford enough protection for freedom of speech.

In July 2021, justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch wrote separate dissenting opinions to a denial of certiorari in the defamation case Berisha v. Lawson, saying that the actual malice standard needed review. Gorsuch argued that the media landscape had changed dramatically since the New York Times decision.

This article was originally published in 2009 and has been updated by encyclopedia staff as recently as July 2021. Stephen Wermiel is a professor of practice at American University Washington College of Law, where he teaches constitutional law, First Amendment and a seminar on the workings of the Supreme Court. He writes a periodic column on SCOTUSblog aimed at explaining the Supreme Court to law students. He is co-author of Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) and The Progeny: Justice William J. Brennan’s Fight to Preserve the Legacy of New York Times v. Sullivan (ABA Publishing, 2014).

Court had said private figures had to show actual malice in matters of public interest

In addition to the standard set for public officials in Sullivan, the Court stated in Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts (1967) that this burden of proof would also have to be met by public figures if they too wished to prevail in these types of suits. These cases left unresolved, however, what the First Amendment required concerning criticism of private individuals.

In Rosenbloom v. Metromedia, Inc. (1971), a plurality of the Supreme Court appeared to extend the Sullivan standard to private individuals if the matter involved discussion of public interest. This was the issue again addressed in Gertz.

cited https://mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/889/actual-malice

Read MORE Below – click the links

We also have the First Amendment Encyclopedia very comprehensive and encompassing

CURRENT TEST = We also have the The ‘Brandenburg test’ for incitement to violence

We also have the The Incitement to Imminent Lawless Action Test

We also have the True Threats Test – Virginia v. Black is most comprehensive Supreme Court definition

We also have the Miller v. California – 3 Prong Obscenity Test (Miller Test) – 1st Amendment 1st

We also have the Obscenity and Pornography ; 1st Amendment

We also have the Watts v. United States – True Threat Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Clear and Present Danger Test

We also have the Gravity of the Evil Test

We also have the Miller v. California – 3 Prong Obscenity Test (Miller Test) – 1st Amendment 1st

We also have the Freedom of the Press – Flyers, Newspaper, Leaflets, Peaceful Assembly – 1st Amendment lots of SCOTUS Rulings

We also have the Insulting letters to politician’s home are constitutionally protected, unless they are ‘true threats’ lots of SCOTUS Rulings

We also have the Introducing TEXT & EMAIL Digital Evidence in California Courts lots of SCOTUS Rulings

California Civil Code Section 52.1 Interference by threat, intimidation or coercion with exercise or enjoyment of individual rights

Recoverable Damages Under 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 LEARN MORE

New Supreme Court Ruling makes it easier to sue police

42 U.S. Code § 1983 – Civil action for deprivation of rights

18 U.S. Code § 242 – Deprivation of rights under color of law

18 U.S. Code § 241 – Conspiracy against rights

Suing for Misconduct – Know More of Your Rights

Police Misconduct in California – How to Bring a Lawsuit

Recoverable Damages Under 42 U.S.C. Section 1983

Section 1983 Lawsuit – How to Bring a Civil Rights Claim