Democracy under Siege

As a lethal pandemic, economic and physical insecurity, and violent conflict ravaged the world, democracy’s defenders sustained heavy new losses in their struggle against authoritarian foes, shifting the international balance in favor of tyranny.

As a lethal pandemic, economic and physical insecurity, and violent conflict ravaged the world in 2020, democracy’s defenders sustained heavy new losses in their struggle against authoritarian foes, shifting the international balance in favor of tyranny. Incumbent leaders increasingly used force to crush opponents and settle scores, sometimes in the name of public health, while beleaguered activists—lacking effective international support—faced heavy jail sentences, torture, or murder in many settings.

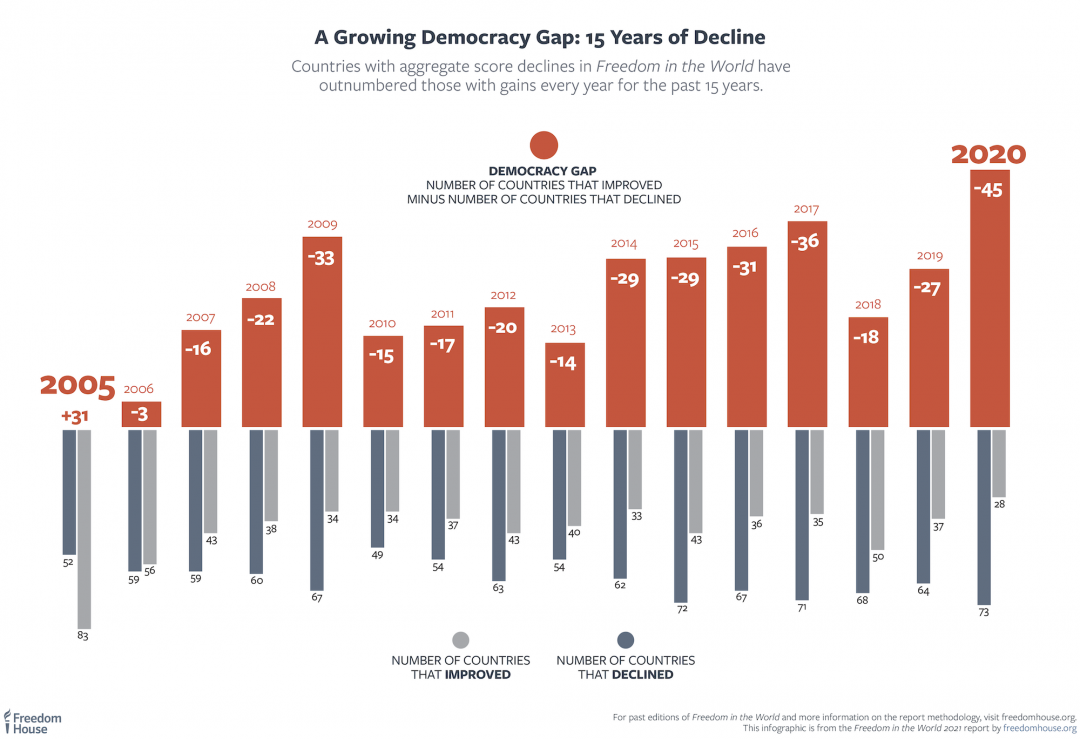

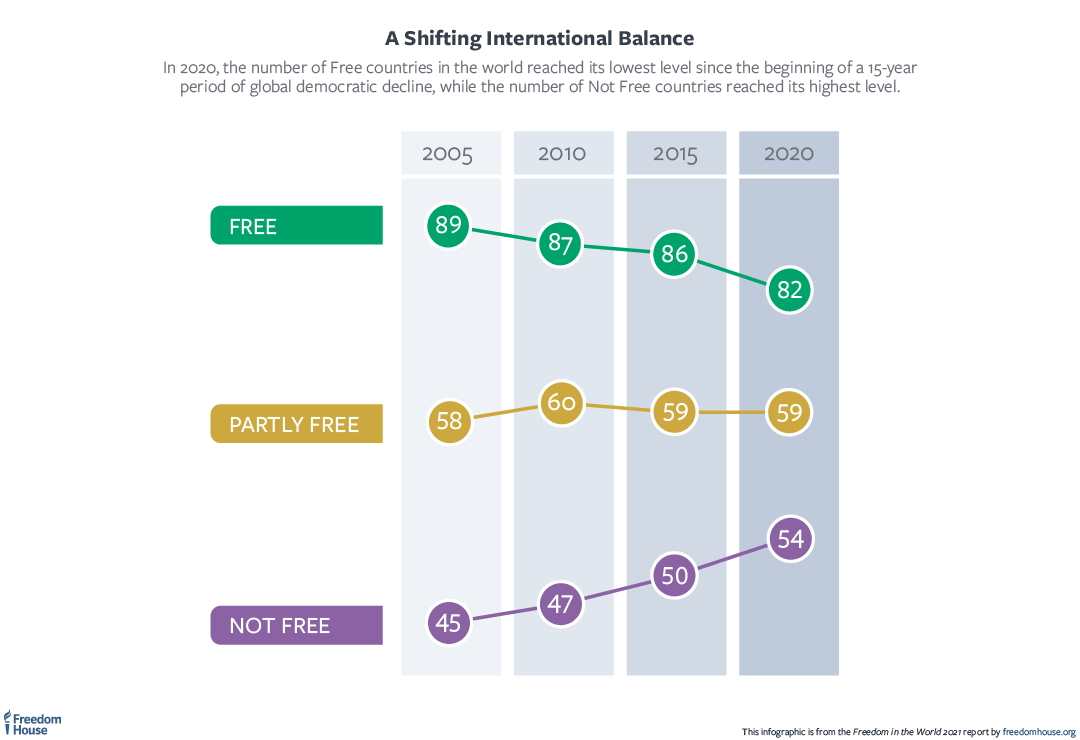

These withering blows marked the 15th consecutive year of decline in global freedom. The countries experiencing deterioration outnumbered those with improvements by the largest margin recorded since the negative trend began in 2006. The long democratic recession is deepening.

The impact of the long-term democratic decline has become increasingly global in nature, broad enough to be felt by those living under the cruelest dictatorships, as well as by citizens of long-standing democracies. Nearly 75 percent of the world’s population lived in a country that faced deterioration last year. The ongoing decline has given rise to claims of democracy’s inherent inferiority. Proponents of this idea include official Chinese and Russian commentators seeking to strengthen their international influence while escaping accountability for abuses, as well as antidemocratic actors within democratic states who see an opportunity to consolidate power. They are both cheering the breakdown of democracy and exacerbating it, pitting themselves against the brave groups and individuals who have set out to reverse the damage.

The malign influence of the regime in China, the world’s most populous dictatorship, was especially profound in 2020. Beijing ramped up its global disinformation and censorship campaign to counter the fallout from its cover-up of the initial coronavirus outbreak, which severely hampered a rapid global response in the pandemic’s early days. Its efforts also featured increased meddling in the domestic political discourse of foreign democracies, transnational extensions of rights abuses common in mainland China, and the demolition of Hong Kong’s liberties and legal autonomy. Meanwhile, the Chinese regime has gained clout in multilateral institutions such as the UN Human Rights Council, which the United States abandoned in 2018, as Beijing pushed a vision of so-called noninterference that allows abuses of democratic principles and human rights standards to go unpunished while the formation of autocratic alliances is promoted.

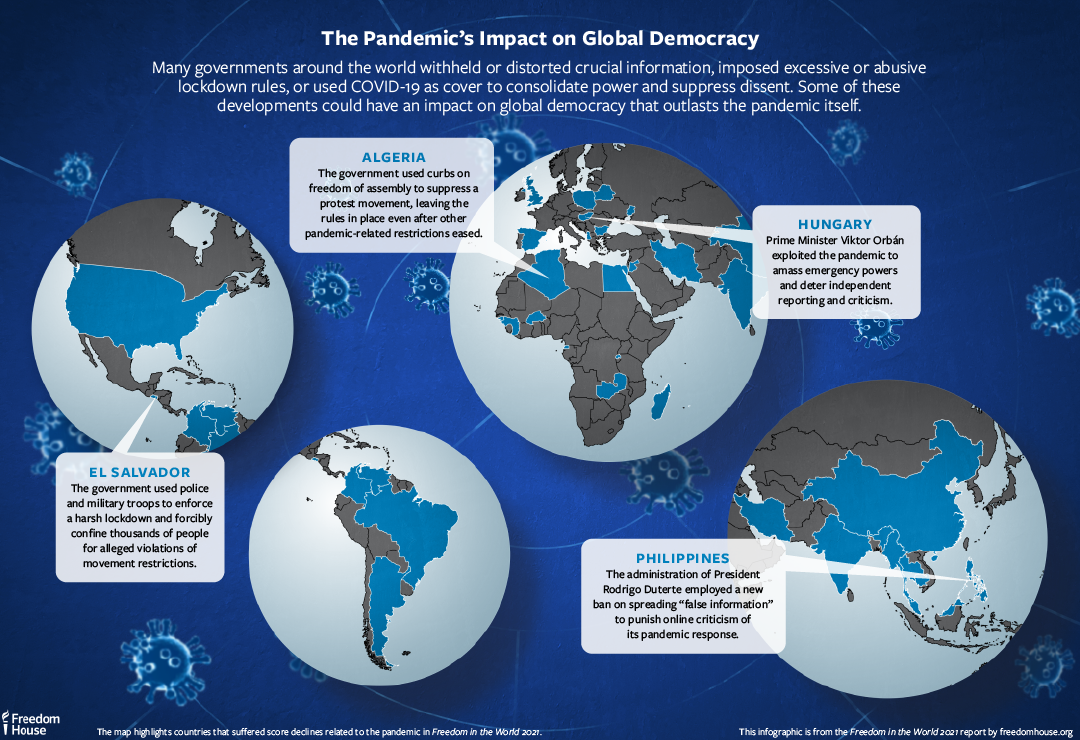

As COVID-19 spread during the year, governments across the democratic spectrum repeatedly resorted to excessive surveillance, discriminatory restrictions on freedoms like movement and assembly, and arbitrary or violent enforcement of such restrictions by police and nonstate actors. Waves of false and misleading information, generated deliberately by political leaders in some cases, flooded many countries’ communication systems, obscuring reliable data and jeopardizing lives. While most countries with stronger democratic institutions ensured that any restrictions on liberty were necessary and proportionate to the threat posed by the virus, a number of their peers pursued clumsy or ill-informed strategies, and dictators from Venezuela to Cambodia exploited the crisis to quash opposition and fortify their power

The expansion of authoritarian rule, combined with the fading and inconsistent presence of major democracies on the international stage, has had tangible effects on human life and security, including the frequent resort to military force to resolve political disputes. As long-standing conflicts churned on in places like Libya and Yemen, the leaders of Ethiopia and Azerbaijan launched wars last year in the regions of Tigray and Nagorno-Karabakh, respectively, drawing on support from authoritarian neighbors Eritrea and Turkey and destabilizing surrounding areas. Repercussions from the fighting shattered hopes for tentative reform movements in both Armenia, which clashed with the Azerbaijani regime over Nagorno-Karabakh, and Ethiopia.

India, the world’s most populous democracy, dropped from Free to Partly Free status in Freedom in the World 2021. The government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and its state-level allies continued to crack down on critics during the year, and their response to COVID-19 included a ham-fisted lockdown that resulted in the dangerous and unplanned displacement of millions of internal migrant workers. The ruling Hindu nationalist movement also encouraged the scapegoating of Muslims, who were disproportionately blamed for the spread of the virus and faced attacks by vigilante mobs. Rather than serving as a champion of democratic practice and a counterweight to authoritarian influence from countries such as China, Modi and his party are tragically driving India itself toward authoritarianism.

The parlous state of US democracy was conspicuous in the early days of 2021 as an insurrectionist mob, egged on by the words of outgoing president Donald Trump and his refusal to admit defeat in the November election, stormed the Capitol building and temporarily disrupted Congress’s final certification of the vote. This capped a year in which the administration attempted to undermine accountability for malfeasance, including by dismissing inspectors general responsible for rooting out financial and other misconduct in government; amplified false allegations of electoral fraud that fed mistrust among much of the US population; and condoned disproportionate violence by police in response to massive protests calling for an end to systemic racial injustice. But the outburst of political violence at the symbolic heart of US democracy, incited by the president himself, threw the country into even greater crisis. Notwithstanding the inauguration of a new president in keeping with the law and the constitution, the United States will need to work vigorously to strengthen its institutional safeguards, restore its civic norms, and uphold the promise of its core principles for all segments of society if it is to protect its venerable democracy and regain global credibility.

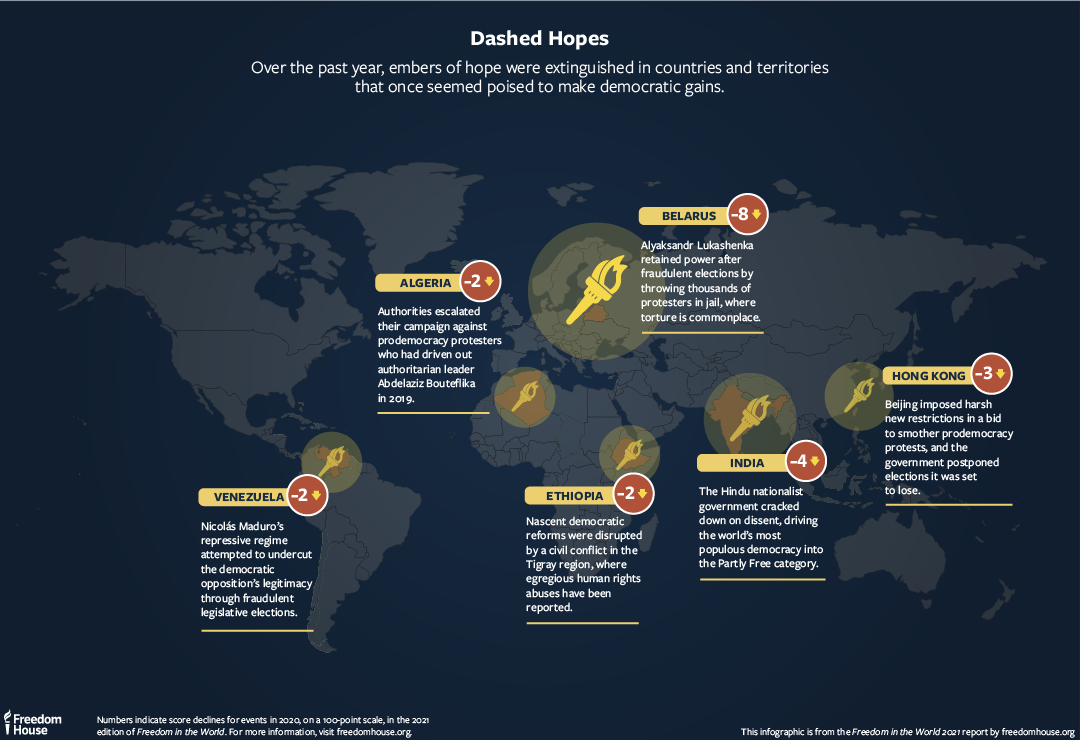

The widespread protest movements of 2019, which had signaled the popular desire for good governance the world over, often collided with increased repression in 2020. While successful protests in countries such as Chile and Sudan led to democratic improvements, there were many more examples in which demonstrators succumbed to crackdowns, with oppressive regimes benefiting from a distracted and divided international community. Nearly two dozen countries and territories that experienced major protests in 2019 suffered a net decline in freedom the following year.

Although Freedom in the World’s better-performing countries had been in retreat for several years, in 2020 it was struggling democracies and authoritarian states that accounted for more of the global decline. The proportion of Not Free countries is now the highest it has been in the past 15 years. On average, the scores of these countries have declined by about 15 percent during the same period. At the same time, the number of countries worldwide earning a net score improvement for 2020 was the lowest since 2005, suggesting that the prospects for a change in the global downward trend are more challenging than ever. With India’s decline to Partly Free, less than 20 percent of the world’s population now lives in a Free country, the smallest proportion since 1995. As repression intensifies in already unfree environments, greater damage is done to their institutions and societies, making it increasingly difficult to fulfill public demands for freedom and prosperity under any future government.

The enemies of freedom have pushed the false narrative that democracy is in decline because it is incapable of addressing people’s needs. In fact, democracy is in decline because its most prominent exemplars are not doing enough to protect it. Global leadership and solidarity from democratic states are urgently needed. Governments that understand the value of democracy, including the new administration in Washington, have a responsibility to band together to deliver on its benefits, counter its adversaries, and support its defenders. They must also put their own houses in order to shore up their credibility and fortify their institutions against politicians and other actors who are willing to trample democratic principles in the pursuit of power. If free societies fail to take these basic steps, the world will become ever more hostile to the values they hold dear, and no country will be safe from the destructive effects of dictatorship.

The shifting international balance

Over the past year, oppressive and often violent authoritarian forces tipped the international order in their favor time and again, exploiting both the advantages of nondemocratic systems and the weaknesses in ailing democracies. In a variety of environments, flickers of hope were extinguished, contributing to a new global status quo in which acts of repression went unpunished and democracy’s advocates were increasingly isolated.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), faced with the danger that its authoritarian system would be blamed for covering up and thus exacerbating the COVID-19 pandemic, worked hard to convert the risk into an opportunity to exert influence. It provided medical supplies to countries that were hit hard by the virus, but it often portrayed sales as donations and orchestrated propaganda events with economically dependent recipient governments. Beijing sometimes sought to shift blame to the very countries it claimed to be helping, as when Chinese state media suggested that the coronavirus had actually originated in Italy. Throughout the year, the CCP touted its own authoritarian methods for controlling the contagion, comparing them favorably with democracies like the United States while studiously ignoring the countries that succeeded without resorting to major abuses, most notably Taiwan. This type of spin has the potential to convince many people that China’s censorship and repression are a recipe for effective governance rather than blunt tools for entrenching political power.

Beyond the pandemic, Beijing’s export of antidemocratic tactics, financial coercion, and physical intimidation have led to an erosion of democratic institutions and human rights protections in numerous countries. The campaign has been supplemented by the regime’s moves to promote its agenda at the United Nations, in diplomatic channels, and through worldwide propaganda that aims to systematically alter global norms. Other authoritarian states have joined China in these efforts, even as key democracies abandoned allies and their own values in foreign policy matters. As a result, the mechanisms that democracies have long used to hold governments accountable for violations of human rights standards and international law are being weakened and subverted, and even the world’s most egregious violations, such as the large-scale forced sterilization of Uighur women, are not met with a well-coordinated response or punishment.

In this climate of impunity, the CCP has run roughshod over Hong Kong’s democratic institutions and international legal agreements. The territory has suffered a massive decline in freedom since 2013, with an especially steep drop since mass prodemocracy demonstrations were suppressed in 2019 and Beijing tightened its grip in 2020. The central government’s imposition of the National Security Law in June erased almost overnight many of Hong Kong’s remaining liberties, bringing it into closer alignment with the system on the mainland. The Hong Kong government itself escalated its use of the law early in 2021 when more than 50 prodemocracy activists and politicians were arrested, essentially for holding a primary and attempting to win legislative elections that were ultimately postponed by a year; they face penalties of up to life in prison. In November the Beijing and Hong Kong governments had colluded to expel four prodemocracy members from the existing Legislative Council, prompting the remaining 15 to resign in protest. These developments reflect a dramatic increase in the cost of opposing the CCP in Hong Kong, and the narrowing of possibilities for turning back the authoritarian tide.

The use of military force by authoritarian states, another symptom of the global decay of democratic norms, was on display in Nagorno-Karabakh last year. New fighting erupted in September when the Azerbaijani regime, with decisive support from Turkey, launched an offensive to settle a territorial dispute that years of diplomacy with Armenia had failed to resolve. At least 6,500 combatants and hundreds of civilians were killed, and tens of thousands of people were newly displaced. Meaningful international engagement was absent, and the war only stopped when Moscow imposed a peacekeeping plan on the two sides, fixing in place the Azerbaijani military’s territorial gains but leaving many other questions unanswered.

The fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh has had spillover effects for democracy. In addition to strengthening the rule of Azerbaijan’s authoritarian president, Ilham Aliyev, the conflict threatens to destabilize the government in Armenia. A rare bright spot in a region replete with deeply entrenched authoritarian leaders, Armenia has experienced tentative gains in freedom since mass antigovernment protests erupted in 2018 and citizens voted in a more reform-minded government. But Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s capitulation in the war sparked a violent reaction among some opponents, who stormed the parliament in November and physically attacked the speaker. Such disorder threatens the country’s hard-won progress, and could set off a chain of events that draws Armenia closer to the autocratic tendencies of its neighbors.

Ethiopia had also made democratic progress in recent years, as new prime minister Abiy Ahmed lifted restrictions on opposition media and political groups and released imprisoned journalists and political figures. However, persistent ethnic and political tensions remained. In July 2020, a popular ethnic Oromo singer was killed, leading to large protests in the Oromia Region that were marred by attacks on non-Oromo populations, a violent response by security forces, and the arrest of thousands of people, including many opposition figures. The country’s fragile gains were further imperiled after the ruling party in the Tigray Region held elections in September against the will of the federal authorities and labeled Abiy’s government illegitimate. Tigrayan forces later attacked a military base, leading to an overwhelming response from federal forces and allied ethnic militias that displaced tens of thousands of people and led to untold civilian casualties. In a dark sign for the country’s democratic prospects, the government enlisted military support from the autocratic regime of neighboring Eritrea, and national elections that were postponed due to the pandemic will now either take place in the shadow of civil conflict or be pushed back even further.

In Venezuela, which has experienced a dizzying 40-point score decline over the last 15 years, some hope arose in 2019 when opposition National Assembly leader Juan Guaidó appeared to present a serious challenge to the rule of dictator Nicolás Maduro. The opposition named Guaidó as interim president under the constitution, citing the illegitimacy of the presidential election that kept Maduro in power, and many democratic governments recognized his status. In 2020, however, as opponents of the regime continued to face extrajudicial execution, enforced disappearances, and arbitrary detention, Maduro regained the upper hand. Tightly controlled National Assembly elections went forward despite an opposition boycott, creating a new body with a ruling party majority. The old opposition-led legislature hung on in a weakened state, extending its own term as its electoral legitimacy ebbed away.

Belarus emerged as another fleeting bright spot in August, when citizens unexpectedly rose up to dispute the fraudulent results of a deeply flawed election. Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s repressive rule had previously been taken for granted, but for a few weeks the protests appeared to put him on the defensive as citizens awakened to their democratic potential despite brutal crackdowns, mass arrests, and torture. By the start of 2021, however, despite ongoing resistance, Lukashenka remained in power, and protests, more limited in scale, continued to be met with detentions. Political rights and civil liberties have become even more restricted than before, and democracy remains a distant aspiration.

In fact, Belarus was far from the only place where the promise of increased freedom raised by mass protests eventually curdled into heightened repression. Of the 39 countries and territories where Freedom House noted major protests in 2019, 23 experienced a score decline for 2020—a significantly higher share than countries with declines represented in the world at large. In settings as varied as Algeria, Guinea, and India, regimes that protests had taken by surprise in 2019 regained their footing, arresting and prosecuting demonstrators, passing newly restrictive laws, and in some cases resorting to brutal crackdowns, for which they faced few international repercussions.

The fall of India from the upper ranks of free nations could have a particularly damaging impact on global democratic standards. Political rights and civil liberties in the country have deteriorated since Narendra Modi became prime minister in 2014, with increased pressure on human rights organizations, rising intimidation of academics and journalists, and a spate of bigoted attacks, including lynchings, aimed at Muslims. The decline only accelerated after Modi’s reelection in 2019. Last year, the government intensified its crackdown on protesters opposed to a discriminatory citizenship law and arrested dozens of journalists who aired criticism of the official pandemic response. Judicial independence has also come under strain; in one case, a judge was transferred immediately after reprimanding the police for taking no action during riots in New Delhi that left over 50 people, mostly Muslims, dead. In December, Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, approved a law that prohibits forced religious conversion through interfaith marriage, which critics fear will effectively restrict interfaith marriage in general; authorities have already arrested a number of Muslim men for allegedly forcing Hindu women to convert to Islam. Amid the pandemic the government imposed an abrupt COVID-19 lockdown in the spring, which left millions of migrant workers in cities without work or basic resources. Many were forced to walk across the country to their home villages, facing various forms of mistreatment along the way. Under Modi, India appears to have abandoned its potential to serve as a global democratic leader, elevating narrow Hindu nationalist interests at the expense of its founding values of inclusion and equal rights for all.

To reverse the global shift toward authoritarian norms, democracy advocates working for freedom in their home countries will need robust solidarity from like-minded allies abroad.

The eclipse of US leadership

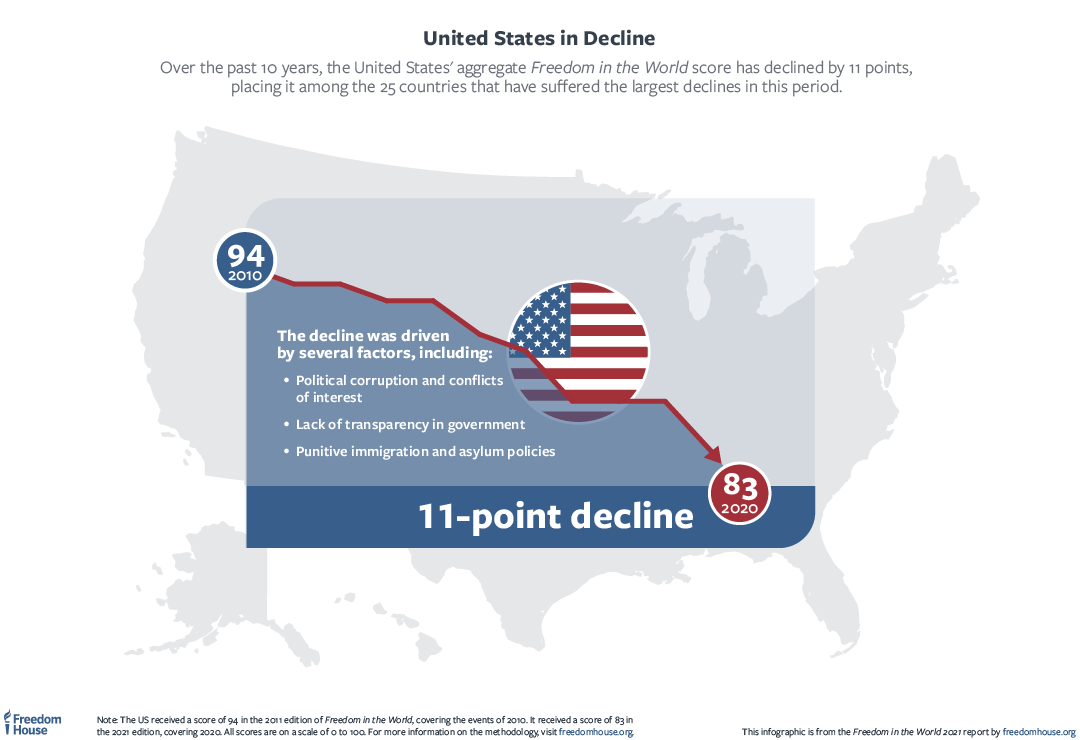

The final weeks of the Trump presidency featured unprecedented attacks on one of the world’s most visible and influential democracies. After four years of condoning and indeed pardoning official malfeasance, ducking accountability for his own transgressions, and encouraging racist and right-wing extremists, the outgoing president openly strove to illegally overturn his loss at the polls, culminating in his incitement of an armed mob to disrupt Congress’s certification of the results. Trump’s actions went unchecked by most lawmakers from his own party, with a stunning silence that undermined basic democratic tenets. Only a serious and sustained reform effort can repair the damage done during the Trump era to the perception and reality of basic rights and freedoms in the United States.

The year leading up to the assault on the Capitol was fraught with other episodes that threw the country into the global spotlight in a new way. The politically distorted health recommendations, partisan infighting, shockingly high and racially disparate coronavirus death rates, and police violence against protesters advocating for racial justice over the summer all underscored the United States’ systemic dysfunctions and made American democracy appear fundamentally unstable. Even before 2020, Trump had presided over an accelerating decline in US freedom scores, driven in part by corruption and conflicts of interest in the administration, resistance to transparency efforts, and harsh and haphazard policies on immigration and asylum that made the country an outlier among its Group of Seven peers.

But President Trump’s attempt to overturn the will of the American voters was arguably the most destructive act of his time in office. His drumbeat of claims—without evidence—that the electoral system was ridden by fraud sowed doubt among a significant portion of the population, despite what election security officials eventually praised as the most secure vote in US history. Nationally elected officials from his party backed these claims, striking at the foundations of democracy and threatening the orderly transfer of power.

Though battered, many US institutions held strong during and after the election process. Lawsuits challenging the result in pivotal states were each thrown out in turn by independent courts. Judges appointed by presidents from both parties ruled impartially, including the three Supreme Court justices Trump himself had nominated, upholding the rule of law and confirming that there were no serious irregularities in the voting or counting processes. A diverse set of media outlets broadly confirmed the outcome of the election, and civil society groups investigated the fraud claims and provided evidence of a credible vote. Some Republicans spoke eloquently and forcefully in support of democratic principles, before and after the storming of the Capitol. Yet it may take years to appreciate and address the effects of the experience on Americans’ ability to come together and collectively uphold a common set of civic values.

The exposure of US democracy’s vulnerabilities has grave implications for the cause of global freedom. Rulers and propagandists in authoritarian states have always pointed to America’s domestic flaws to deflect attention from their own abuses, but the events of the past year will give them ample new fodder for this tactic, and the evidence they cite will remain in the world’s collective memory for a long time to come. After the Capitol riot, a spokesperson from the Russian foreign ministry stated, “The events in Washington show that the US electoral process is archaic, does not meet modern standards, and is prone to violations.” Zimbabwe’s president said the incident “showed that the US has no moral right to punish another nation under the guise of upholding democracy.”

For most of the past 75 years, despite many mistakes, the United States has aspired to a foreign policy based on democratic principles and support for human rights. When adhered to, these guiding lights have enabled the United States to act as a leader on the global stage, pressuring offenders to reform, encouraging activists to continue their fight, and rallying partners to act in concert. After four years of neglect, contradiction, or outright abandonment under Trump, President Biden has indicated that his administration will return to that tradition. But to rebuild credibility in such an endeavor and garner the domestic support necessary to sustain it, the United States needs to improve its own democracy. It must strengthen institutions enough to survive another assault, protect the electoral system from foreign and domestic interference, address the structural roots of extremism and polarization, and uphold the rights and freedoms of all people, not just a privileged few.

Everyone benefits when the United States serves as a positive model, and the country itself reaps ample returns from a more democratic world. Such a world generates more trade and fairer markets for US goods and services, as well as more reliable allies for collective defense. A global environment where freedom flourishes is more friendly, stable, and secure, with fewer military conflicts and less displacement of refugees and asylum seekers. It also serves as an effective check against authoritarian actors who are only too happy to fill the void.

The long arm of COVID-19

Since it spread around the world in early 2020, COVID-19 has exacerbated the global decline in freedom. The outbreak exposed weaknesses across all the pillars of democracy, from elections and the rule of law to egregiously disproportionate restrictions on freedoms of assembly and movement. Both democracies and dictatorships experienced successes and failures in their battle with the virus itself, though citizens in authoritarian states had fewer tools to resist and correct harmful policies. Ultimately, the changes precipitated by the pandemic left many societies—with varied regime types, income levels, and demographics—in worse political condition; with more pronounced racial, ethnic, and gender inequalities; and vulnerable to long-term effects.

Transparency was one of the hardest-hit aspects of democratic governance. National and local officials in China assiduously obstructed information about the outbreak, including by carrying out mass arrests of internet users who shared related information. In December, citizen journalist Zhang Zhan was sentenced to four years in prison for her reporting from Wuhan, the initial epicenter. The Belarusian government actively downplayed the seriousness of the pandemic to the public, refusing to take action, while the Iranian regime concealed the true toll of the virus on its people. Some highly repressive governments, including those of Turkmenistan and Nicaragua, simply ignored reality and denied the presence of the pathogen in their territory. More open political systems also experienced significant transparency problems. At the presidential level and in a number of states and localities, officials in the United States obscured data and actively sowed misinformation about the transmission and treatment of the coronavirus, leading to widespread confusion and the politicization of what should have been a public health matter. Similarly, Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro repeatedly downplayed the harms of COVID-19, promoted unproven treatments, criticized subnational governments’ health measures, and sowed doubt about the utility of masks and vaccines.

Freedom of personal expression, which has experienced the largest declines of any democracy indicator since 2012, was further restrained during the health crisis. In the midst of a heavy-handed lockdown in the Philippines under President Rodrigo Duterte, the authorities stepped up harassment and arrests of social media users, including those who criticized the government’s pandemic response. Cambodia’s authoritarian prime minister, Hun Sen, presided over the arrests of numerous people for allegedly spreading false information linked to the virus and criticizing the state’s performance. Governments around the world also deployed intrusive surveillance tools that were often of dubious value to public health and featured few safeguards against abuse.

But beyond their impact in 2020, official responses to COVID-19 have laid the groundwork for government excesses that could affect democracy for years to come. As with the response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, when the United States and many other countries dramatically expanded their surveillance activities and restricted due process rights in the name of national security, the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a shift in norms and the adoption of problematic legislation that will be challenging to reverse after the virus has been contained.

In Hungary, for example, a series of emergency measures allowed the government to rule by decree despite the fact that coronavirus cases were negligible in the country until the fall. Among other misuses of these new powers, the government withdrew financial assistance from municipalities led by opposition parties. The push for greater executive authority was in keeping with the gradual concentration of power that Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has been orchestrating over the past decade. An indicative move came in December, when the pliant parliament approved constitutional amendments that transferred public assets into the hands of institutions headed by ruling-party loyalists, reduced independent oversight of government spending, and pandered to the ruling party’s base by effectively barring same-sex couples from adopting children.

In Algeria, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune, who had recently taken office through a tightly controlled election after longtime authoritarian leader Abdelaziz Bouteflika resigned under public pressure, banned all forms of mass gatherings in March. Even as other restrictions were eased in June, the prohibition on assembly remained in place, and authorities stepped up arrests of activists associated with the prodemocracy protest movement. Many of the arrests were based on April amendments to the penal code, which had been adopted under the cover of the COVID-19 response. The amended code increased prison sentences for defamation and criminalized the spread of false information, with higher penalties during a health or other type of emergency—provisions that could continue to suppress critical speech in the future.

Indonesia turned to the military and other security forces as key players in its pandemic response. Multiple military figures were appointed to leading positions on the country’s COVID-19 task force, and the armed services provided essential support in developing emergency hospitals and securing medical supplies. In recent years, observers have raised concerns about the military’s growing influence over civilian governance, and its heavy involvement in the health crisis threatened to accelerate this trend. Meanwhile, restrictions on freedoms of expression and association have worsened over time, pushing the country’s scores deeper into the Partly Free range.

In Sri Lanka, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa dissolved the parliament in early March, intending to hold elections the following month. The pandemic delayed the vote, however, giving Rajapaksa the opportunity to rule virtually unchecked and consolidate power through various ministerial appointments. After his party swept the August elections, the new parliament approved constitutional amendments that expanded presidential authority, including by allowing Rajapaksa to appoint electoral, police, human rights, and anticorruption commissions. The changes also permitted the chief executive to hold ministerial positions and dissolve the legislature after it has served just half of its term.

The public health crisis is causing a major economic crisis, as countries around the world fall into recession and millions of people are left unemployed. Marginalized populations are bearing the brunt of both the virus and its economic impact, which has exacerbated income inequality, among other disparities. In general, countries with wider income gaps have weaker protections for basic rights, suggesting that the economic fallout from the pandemic could have harmful implications for democracy. The global financial crisis of 2008–09 was notably followed by political instability and a deepening of the democratic decline.

The COVID-19 pandemic is not the only current global emergency that has the potential to hasten the erosion of democracy. The effects of climate change could have a similar long-term impact, with mass displacement fueling conflict and more nationalist, xenophobic, and racist policies. Numerous other, less predictable crises could also surface, including new health emergencies. Democracy’s advocates need to learn from the experience of 2020 and prepare for emergency responses that respect the political rights and civil liberties of all people, including the most marginalized.

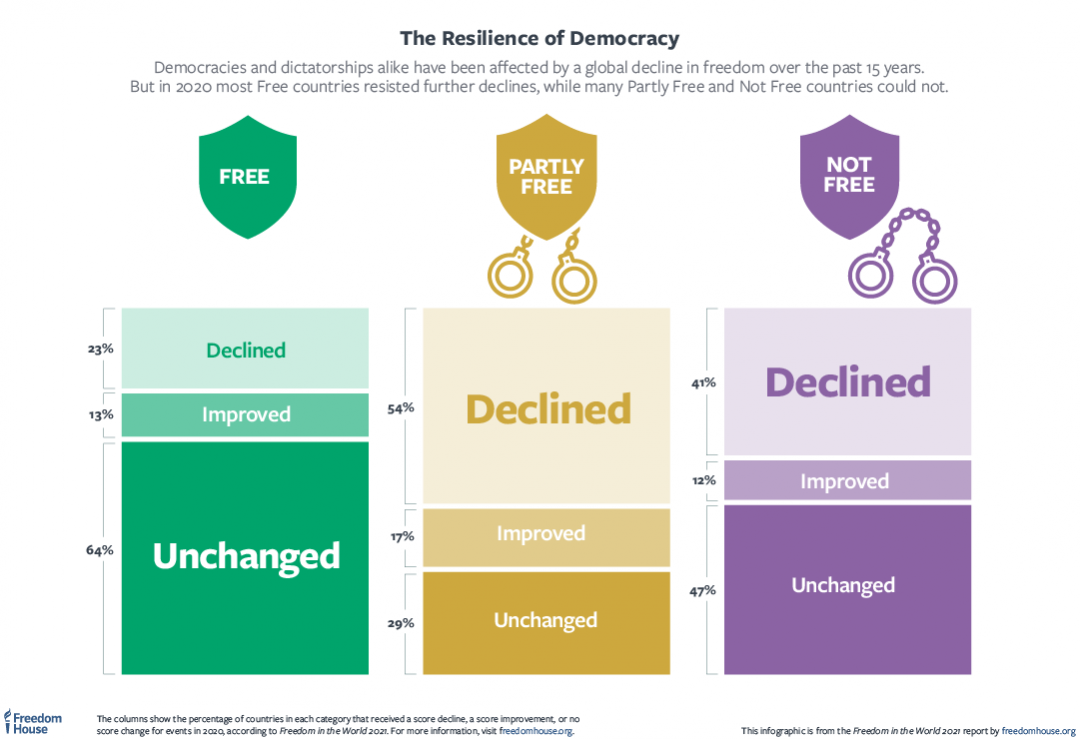

The resilience of democracy

A litany of setbacks and catastrophes for freedom dominated the news in 2020. But democracy is remarkably resilient, and has proven its ability to rebound from repeated blows.

A prime example can be found in Malawi, which made important gains during the year. The Malawian people have endured a low-performing democratic system that struggled to contain a succession of corrupt and heavy-handed leaders. Although mid-2019 national elections that handed victory to the incumbent president were initially deemed credible by local and international observers, the count was marred by evidence that Tipp-Ex correction fluid was used to alter vote tabulation sheets. The election commission declined to call for a new vote, but opposition candidates took the case to the constitutional court. The court resisted bribery attempts and issued a landmark ruling in February 2020, ordering fresh elections. Opposition presidential candidate Lazarus Chakwera won the June rerun vote by a comfortable margin, proving that independent institutions can hold abuse of power in check. While Malawi is a country of 19 million people, the story of its election rerun has wider implications, as courts in other African states have asserted their independence in recent years, and the nullification of a flawed election—for only the second time in the continent’s history—will not go unnoticed.

Taiwan overcame another set of challenges in 2020, suppressing the coronavirus with remarkable effectiveness and without resorting to abusive methods, even as it continued to shrug off threats from an increasingly aggressive regime in China. Taiwan, like its neighbors, benefited from prior experience with SARS, but its handling of COVID-19 largely respected civil liberties. Early implementation of expert recommendations, the deployment of masks and other protective equipment, and efficient contact-tracing and testing efforts that prioritized transparency—combined with the country’s island geography—all helped to control the disease. Meanwhile, Beijing escalated its campaign to sway global opinion against Taiwan’s government and deny the success of its democracy, in part by successfully pressuring the World Health Organization to ignore early warnings of human-to-human transmission from Taiwan and to exclude Taiwan from its World Health Assembly. Even before the virus struck, Taiwanese voters defied a multipronged, politicized disinformation campaign from China and overwhelmingly reelected incumbent president Tsai Ing-wen, who opposes moves toward unification with the mainland.

More broadly, democracy has demonstrated its adaptability under the unique constraints of a world afflicted by COVID-19. A number of successful elections were held across all regions and in countries at all income levels, including in Montenegro, and in Bolivia, yielding improvements. Judicial bodies in many settings, such as The Gambia, have held leaders to account for abuses of power, providing meaningful checks on the executive branch and contributing to slight global gains for judicial independence over the past four years. At the same time, journalists in even the most repressive environments like China sought to shed light on government transgressions, and ordinary people from Bulgaria to India to Brazil continued to express discontent on topics ranging from corruption and systemic inequality to the mishandling of the health crisis, letting their leaders know that the desire for democratic governance will not be easily quelled.

The Biden administration has pledged to make support for democracy a key part of US foreign policy, raising hopes for a more proactive American role in reversing the global democratic decline. To fulfill this promise, the president will need to provide clear leadership, articulating his goals to the American public and to allies overseas. He must also make the United States credible in its efforts by implementing the reforms necessary to address considerable democratic deficits at home. Given many competing priorities, including the pandemic and its socioeconomic aftermath, President Biden will have to remain steadfast, keeping in mind that democracy is a continuous project of renewal that ultimately ensures security and prosperity while upholding the fundamental rights of all people.

Democracy today is beleaguered but not defeated. Its enduring popularity in a more hostile world and its perseverance after a devastating year are signals of resilience that bode well for the future of freedom. source

Most people in advanced economies think their own government respects personal freedoms

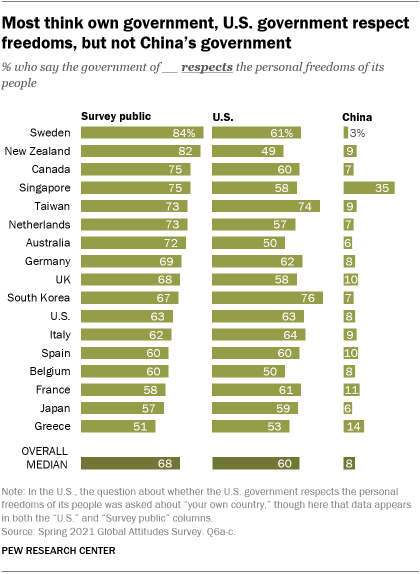

Governments in 17 advanced economies generally get good marks from their citizens when it comes to how much they respect their own people’s personal freedoms. And people in most of the publics surveyed view their own government’s record on personal freedoms more favorably than that of the United States and especially China.

Here are five key findings on this topic based on a spring 2021 Pew Research Center survey in 17 advanced economies, conducted from Feb. 1 to May 26, 2021, among 18,850 adults.

Most people think their own government does respect the personal freedoms of its people. A median of 68% across the 17 publics surveyed say this, including more than half in every place surveyed. Swedes and New Zealanders are most likely to praise their governments – 84% and 82%, respectively – but around three-quarters say the same in Canada, Singapore, Taiwan, the Netherlands and Australia. Only in Greece, Japan and France do fewer than six-in-ten say their government respects the personal freedoms of its people.

In most places surveyed, more say their own government respects the personal freedoms of its people than say the same of the U.S. The difference is largest in New Zealand, where 82% say their own government respects the personal freedoms of its people, but only 49% say the same of the U.S. In Australia and Sweden, too, the difference is more than 20 percentage points. Only in Spain, Taiwan, Japan, Italy, Greece and France are evaluations of the U.S. comparable to those of their own government – and in many cases these publics are the ones that are most critical of their own governments.

Evaluations of people’s own governments are substantially more positive than their assessments of the Chinese government. A median of only 8% think the Chinese government respects the personal freedoms of its people. Roughly one-in-ten or fewer hold this view in all places surveyed except Singapore and Greece, where 34% and 14%, respectively, think China respects the personal freedoms of its people.

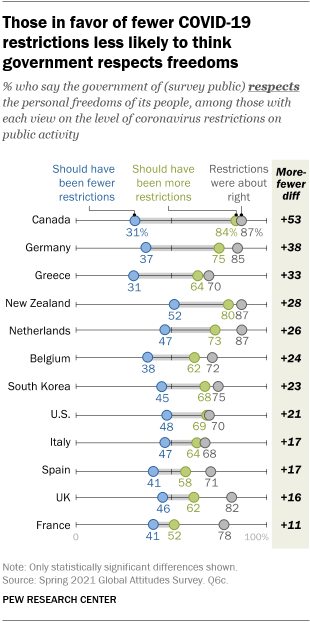

Whether people think their own government respects personal freedoms is often related to how people view COVID-19 restrictions. In most places surveyed, those who think restrictions put in place for the coronavirus were about right or who favored more restrictions are much more likely to say their government respects their people’s personal freedoms than those who wanted fewer restrictions. In the U.S., around seven-in-ten of those who think restrictions were appropriate, or desired even more, say the U.S. respects personal freedoms, compared with 48% of those who wanted fewer restrictions.

Notably, in many publics, those who say racial and ethnic discrimination is a problem in their own society are not consistently more likely to criticize their government’s handling of personal freedoms, suggesting that views of personal freedoms are informed by more than racial conflicts within a society.

Ideology and partisanship both play a role in coloring evaluations of how governments are performing on personal freedoms. In six of the places surveyed, those on the ideological right are more likely to say the U.S. respects the personal freedoms of its people. Those on the ideological right also tend to have more favorable views of the U.S. When it comes to evaluations of one’s own government, though, the impact of ideology varies somewhat. In the U.S., Canada, Germany, Italy, Sweden, New Zealand and South Korea, those on the left are more likely to say the government respects personal freedoms than those on the right. In contrast, in France, Greece and Australia, the opposite is true: Those on the right are more likely to describe their government in these favorable terms.

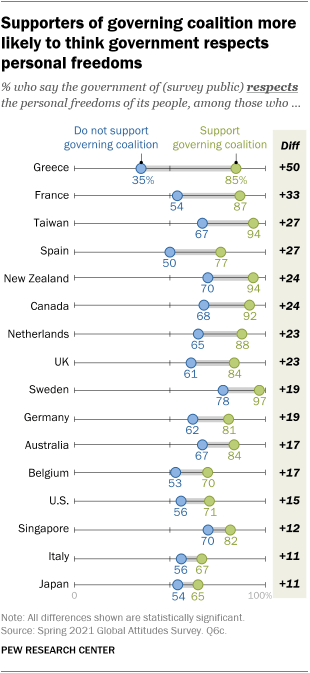

Views of personal freedoms in one’s own society are largely related to support for the governing party. Supporters of the governing party in each of the advanced economies surveyed are more likely to say that their government respects personal freedoms than those who do not support the governing party (South Korea is excluded here because party ID is not asked). For example, in Taiwan, 94% of those who support the currently governing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) say that their government respects personal freedoms, compared with 67% of those who support opposition parties, including the Kuomintang (KMT). source

The Decline of Freedom of Expression and Social Vulnerability in Western democracy

Freedom of expression is a fundamental part of living in a free and open society and, above all, a basic need of every human being and a requirement to attain happiness. Its absence has relevant consequences, not only for individuals but also for the whole social community. This might explain why freedom of expression was, along with other freedoms (conscience and religion; thought, belief, opinion, including that of the press and other media of communication; peaceful assembly; and association), at the core of liberal constitutionalism, and constitutes, since the Second World War, an essential element of constitutional democracies. In a democracy, people should be allowed to express themselves to others freely. The paper, which is divided into five sections, points out that states are obliged to protect the exercise of that freedom not only because its very purpose is the common good and welfare of society but also because it is a requirement of any constitutional democracy. Otherwise, when people cannot express themselves, perhaps out of fear (not from ‘war’ but from different kinds of social pressure or ‘violence’ exerted by some lobbies, mass media, or governmental policies that are at odds with respect for the plurality of opinions), vulnerability arises. This weakens not only those individuals that are not allowed to express their thoughts but also those who do not dare to do it – or even not to think for themselves – under certain environmental pressures (exerted by states, international organizations, social media, or financial groups, lobbies, etc.). In the end, the decline of freedom of expression makes most people more vulnerable and jeopardizes the whole democratic system.

Introduction

Freedom of expression is a fundamental part of living in a free and open society and, above all, a basic need of every human being. From a legal perspective, freedom of expression was, along with other freedoms (conscience and religion; thought, belief, opinion, including that of the press and other media of communication; peaceful assembly; and association), at the core of liberal constitutionalism. It also constitutes, since the Second World War, an essential element of constitutional democracies [1]. In the 1941 State of the Union address, on Monday, 6th January 1941, in proposing four fundamental freedoms that people ought to enjoy, Franklin D. Roosevelt stated that “[t]he first is the freedom of speech and expression everywhere in the world”, followed by other three freedoms (of worship, from want and fear). As America entered the war, these “four freedoms” symbolized America’s war aims and gave hope in the following years to a war-wearied people because they knew they were fighting for freedom. Roosevelt equated “Freedom from fear” mainly with overcoming war and violence. [2, 266–283].

This paper is divided into two parts. Part 1 will describe the relationship between public morality, freedom of expression and right to dissent in a democracy. This will be done with four sections: Sect. 2.1 will contain a brief presentation of the freedom of speech in the origins of modern constitutionalism; Sect. 2.2 will show the inextricable link between democracy and public morality and the two main models of the latter (libertarianism and perfectionism); Sect. 2.3. Argues that, since public morality is a constituent part of any democratic society and a deliberative democracy requires that decisions be the product of fair and reasonable discussion and debate among citizens, public morality should be also shaped by citizens through the exercise of freedom of expression. In doing so, I will describe how to combine, in an open and plural society, the private morality of individuals in the social realm and the public morality reflected in the legal realm, and how democratic systems should allow – and even foster – through the exercise of freedom of expression, a constant flux between private moralities and public morality; and Sect. 2.4. Argues that the freedom of expression necessarily requires the right to dissent because that is an essential part of its exercise, particularly in a deliberative democracy, and a human need according to the Aristotelian characterization of man as a political animal.

Part 2 will describe how the current freedom of expression crisis weakens society, making individuals less engaged in the community, more isolated, as if they were living among strangers, and, consequently, much more vulnerable. This part will be developed in four sections: Sect. 3.1. Will show how the freedom of expression constitutes a condition for political liberalism (enhancing human development and social happiness); Sect. 3.2. Will focus on the freedom of expression as a condition for democracy; Sect. 3.3. Will show the threads of freedom of expression today, analyzing the vulnerable effects of the cancel culture; and Sect. 3.4. Will show, as a particular case of criminalization of dissent, recent examples from Spanish law. Finally, some concluding remarks will be made.

Public Morality, Freedom of Expression and Right to Dissent in a Democracy

The Making of Freedom of Expression in Modern Constitutionalism

Freedom of expression is one of the most complex fundamental rights in modern Constitutions. This complexity is not new. It always has been [3]. Freedom of expression was already very present in the European enlightened cultural environment. Kant affirmed that “everyone has his inalienable rights, which he cannot give up even if he wishes to, and about which he is entitled to make his own judgments.” Furthermore, he added that among them was:

the right to publicly make his opinion known as what he considers unjust to the community in the sovereign’s provisions. To admit that the sovereign cannot even be mistaken or ignorant of anything would be to imagine him as a superhuman being endowed with heavenly inspiration. Consequently, the freedom of writing is the only defender of the rights of the people, as long as it remains within the limits of respect and love for the Constitution in which it lives, thanks to the liberal way of thinking of the subjects, which are also instilled by that Constitution, for which the writings further limit themselves mutually in order not to lose their freedom [4–6].

This cultural environment had consequences in the legal sphere [7]. First of all, in France, where on 26th August 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was drafted, Article 11 of which reads as follows:

The unrestrained communication of thoughts and opinions being one of the most precious rights of man, every citizen may speak, write, and publish freely, provided he is responsible for the abuse of this liberty, in cases determined by law.

This principle was taken up two years later in the first French Constitution, 3rd September 1791, by establishing as natural and civil rights “the liberty to every man to speak, write, print, and publish his opinions.” This freedom did not only germinate in Europe but also in America. A few months after the aforementioned French constitutional text, the United States adopted the First Amendment to its 1791 Constitution:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

It is possible that the following statement by Alexis de Tocqueville emerged from the North-American experience:

Sovereignty of the people and freedom of the press are two entirely correlative things. Censorship and universal suffrage are, on the contrary, two things that contradict each other and that cannot exist together for long in the political institutions of the same people [21:3].

In Spain, freedom of expression emerged in the context of the War of Independence (1808–1814). Specifically, the Cortes of Cadiz approved two Decrees in this regard, one of 10th November 1810 and the other of 10th June 1813. Article 371 of the Constitution of Cadiz (1812), taking up Article I of the 1810 Decree, provided:

All Spaniards are free to write, print and publish their political ideas without the need for any license, revision or approval prior to publication, subject to the restrictions and liability established by law.

The 1869 Constitution was particularly relevant because it referred, for the first time, to the oral expression of thought, in its Article 17:

Nor may any Spaniard be deprived: Of the right to freely express their ideas and opinions, either orally or in writing, by means of the printing press or any other similar process.

Until then, freedom of (oral) expression was understood to be included within the freedom of written expression, that is, freedom of the press and printing press.

The other Spanish Constitutions took up freedom of expression in general from that time onwards, sometimes explicitly mentioning orality. Thus, for example, the Preliminary Title of the Draft Federal Constitution of the First Spanish Republic (1874) after stating that “Every person is assured in the Republic, without any power having the power to inhibit them, nor any law authority to diminish them, all natural rights”, included “the right to the free exercise of thought and the free expression of conscience.” Shortly afterward, the Constitution of 1876 established, in Article 13, that:

Every Spaniard has the right: To freely express their ideas and opinions, either by word or in writing, by means of the printing press or any other similar process, without being subject to prior censorship.

In similar terms, this right was enshrined in Article 34 of the Constitution of the Second Republic (1931):

Everyone has the right to freely express their ideas and opinions, using any means of dissemination, without being subject to prior censorship.

However, one might ask how the exercise of this right worked in practice throughout Spanish constitutionalism.1 The answer can be found in the literature showing the complexity of exercising this freedom [8]. During the Liberal Triennium (1820–1823), for example, it seems that the freedom of expression encountered two groups that threatened its exercise within the strict constitutional framework. First, there were some clergymen, whose sermons could become highly critical of the constitutional regime, thus leading to the approval of a statute (‘Orden’) of 30th April 1821. Second to object were some in the exalted sector of liberalism, which used freedom of the press to incite disobedience, slander, disorder, and anarchy. As a result of the concern for the correct exercise of freedom of expression, several Decrees were passed during the Liberal Triennium: 22nd October 1820, and the complementary Decrees of 17th April 1821 and 12th February 1822. The first Spanish Criminal Code also included several criminal offenses, which came to limit the framework for exercising this freedom. And so have all the criminal codes up to the present day (1848/50, 1870, 1928, 1932, 1944, and 1995).

This brief historical introduction to the freedom of expression is enough to show that the exercise of this right, present since the origins of modern constitutionalism, has always had – and will continue to have – enemies. In the nineteenth century, it was some ecclesiastics and some exalted liberals: some preventing expression on matters of faith and morals, others inciting disobedience, slander and disorder. At present, some essential requirements for the exercise of freedom of expression in the framework of plural and mature democratic societies are notably neglected: to reflect critically on the problems, to think for oneself, respectfully express one’s ideas, and adopt a positive attitude of listening to others, in order to learn from everyone and in particular from those who do not share one’s way of thinking. These are the inescapable conditions of freedom of expression that the law must safeguard and foster. Otherwise, the free development of each individual’s personality is precluded (art. 10 CE), other freedoms are curtailed (such as those of thought and conscience), and democracy becomes a formal or aesthetic reality, void of content and subject to various forces of totalitarian domination. In this vein – as will be seen –, to prohibit the expression of dissent on controversial issues (such as the beginning and end of life, family, sexual morality, etc.) would be to return – at the very least – to the regime of freedom of expression of the early nineteenth century, in which questions of Christian faith and morals were excluded from the exercise of freedom of expression, and anyone who expressed dissent was punished.

I can understand – although one might disagree with it – that this would happen in the framework of a confessional or denominational state (as in the nineteenth century). However, it would make no sense in today’s framework of constitutional democracy. In this sense, the use of double standards when judging – or even legislating – the scope and limits of the exercise of freedom of expression and freedom of information, depending on for what and for whom, preventing some from even speaking and allowing others to insult and slander, not only constitutes an unequivocal sign of a broken and sick democracy – perhaps deathly – but it leaves all its individuals, both those who choose to conform to the majority opinion and those who are willing to express their disagreement, in a vulnerable situation. This vulnerability of individuals is a reflection of the fragility of democracy. The strengthening of democracy also implies strengthening individuals and vice versa. For this, the safeguarding and fostering of freedom of expression constitute a sine qua non requirement.

Public Morality and its Models: Libertarianism vs. Perfectionism

In a true, rather than in a merely formal democracy, the exercise of freedom of expression by citizens should be the fundamental element in shaping the public morality of society. A citizen might feel more or less identified with a particular public ethic, but he/she should never ignore it. Furthermore, the law should promote the contribution of each individual in the never-ending process of shaping public morality. However, what exactly is public morality?

Public morality is a reality, whether we like it or not [4, 9–12]. Ultimately, it is that set of beliefs and values generally assumed by society, by each society, which has its differential elements depending on the geographical context and that tend to change and evolve over time [13, 268–277]. The values that underpin a country’s society at a given moment in history – like the transition, for instance – can have little to do with the values that the same society is underpinned by sometime later.2

A society cannot fail to be based on principles and values that its citizens widely accept. The common acceptance of these principles and values (public ethics) builds stable societies, even though some people may claim otherwise or proclaim themselves liberal and present themselves as supposedly neutral towards any value or ethical principle. Being liberal does not imply being unethical, but it entails assuming a specific type of ethics. There is a liberal who tends to present himself as tolerant and boasts of respecting all positions but accuses those who do not share his stance of being intolerant and of attempting to impose their ethics on the rest of society. This is a well-known demagogic device that nevertheless leaves many without knowing what to say or how to respond. This is the stance adopted by the so-called ‘Libertarianism’ movement in the United States, whose supporters take the liberty of criticizing – and even disqualifying – those who maintain that society needs somewhat more demanding ethical rules that guarantee a minimum of standards of justice that are indispensable for stable and peaceful coexistence [14].3

For libertarians, freedom is the fundamental ethical principle. Invoking an ethical demand to reduce a person’s capacity to make choices and decisions in any area is interpreted as an illegitimate interference or an unacceptable encroachment. Libertarians understand that no one can be constrained or limited in their decisions by any ethical imperative that seeks to impose on one’s own will [3, 6, 13, 15–24].4 For this conception, it would be just as unacceptable to force someone to end their life as it would be to prevent someone from being able to make that decision if that is what they desire. It would be just as unacceptable to force a woman to have an abortion as it would be to forbid her from having one if that is what she wishes. It would be just as unacceptable to force someone into prostitution as it would be to stop them from doing so if that is what they want. It would be just as unacceptable to force someone to try drugs as it would be to prohibit them from doing so if this was their will, and so on. The same applies to many other areas like economics (capitalism, communism, liberalism, neoliberalism, protectionism, etc.) or sexuality (prostitution, pornography, bigamy, pedophilia, polygamy/polyandry, polyamory, incest, etc.), among others.

At the other extreme is the so-called ‘Perfectionism’ trend, which upholds more rigorous standards of public ethics. Its supporters believe that it is the virtue that should guarantee justice and social peace and that the climate of the political community should favor the virtuous conduct of its individuals. In short, they argue that society should contribute to shaping citizens of exemplary conduct, thus positively impacting society as a whole. According to this perspective, the fundamental ethical principle is not so much the freedom of choice advocated by ‘libertarianism’ but the idea of the good, the promotion of virtuous conduct, and the idea of the good shared by society. From this point of view, in order to tackle complex issues (euthanasia, abortion, drugs, prostitution, incest, polygamy, etc.) [12, 521–538, 21, 320–358], the important thing would not be to “let everyone do what they want” – because the political community should neither oblige nor prohibit (libertarians) [25]5 – but to establish “what is good for the individual and society as a whole,” a doctrine which has its roots in authors such as Plato [26], Aristotle [27], and Thomas Aquinas [28, 29], among others [2, 7, 17, 22–27, 30–58].6

Both currents, present in some form in all Western societies, are irreconcilable and struggle to impose themselves on the public ethics of each political community. To attain this, they need to introduce their presuppositions into education, culture, the media, social networks, cinema, literature, etc. Moreover, the quickest way to achieve this is to introduce them into government programs and to use the law as a tool for change. With the law, it is somehow swift and easy to reform education, making it possible to mold the minds of an entire generation in little more than a decade through the curricula of compulsory education. By changing the laws [2, 7, 9, 25–27, 30–50, 57], history and language can be changed, even at the cost of trampling its scientific status with ideological or partisan manipulations. Power can favor a particular type of culture (cinema, art, etc.) by subsidizing television channels and media groups that disseminate it and ignoring others; it can also bail out certain companies while leaving others to go under, etc.

This is well known to everyone, but it is occasionally forgotten that the libertarian currents are not as innocent as they preach and use the law to impose their principles, as much or more than the perfectionist currents, despite presenting their measures or legal reforms as ethically aseptic. In this sense, promoting a law that prohibits euthanasia, opting instead to promote palliative medicine and care for the terminally ill, so that they prefer to live rather than die, should be considered as moral – or immoral, depending on one’s position – as promoting another law which financially supports those who decide to end their lives [59, 60]. One can disagree about what is ethically correct, but it cannot be stated that the first of these proposals imposes an ethical option and the other does not. There is a clear and undeniable ethical background in both [57], even if the second neither prohibits nor compels and subsidizes an individual’s wish to die, while the other prohibits killing and funds better care for the sick by facilitating their access to palliative care in the hope that they will prefer to continue living.

In my case, I must admit that, precisely because I believe in and love freedom, I do not identify myself with libertarians or perfectionists. I do not identify with the former because it does not seem reasonable to me to maintain that freedom, understood as a mere capacity to choose, is a guarantee of a truly human life and society; in fact, it is evident that there are decisions that make one better as a person (for example, trying to work well and in a spirit of service to others) and others that make one worse (working shoddily, trying to look good or cheating others). Nor do I identify with the latter when perfectionism is interpreted as the imposition of an idea of the good that is totalitarian and disrespectful to the individual because I understand that it should be each person who freely decides for the good and should never adhere to it “forced” by a paternalistic government or laws that do not allow one to choose the opposite.

I understand that the law must safeguard and foster minimum requirements of justice, reflected in the three basic rules of the jurist Ulpian: live honestly, do not harm others, and give each one what is theirs. However, the State and the Law should not go beyond these requirements (because their task is not to make citizens good but to create the minimum conditions of justice that allow a stable and peaceful coexistence). In reality, only everyone can become good (and not just fair) when they freely choose to do what is good (not merely fair) and do it for a good or right reason (and not because it is so legally prescribed). Neither the State nor the Law can make me good: I can only become good when I freely choose to do what is good and do it for a good (or right) reason. In case the State or the Law forced someone to do good (in the event that this was legally prescribed), that by itself would not make him/her a good person because there would be a lack of freedom (to do it for being good and not for being legally mandated). Only from freedom – not from imposition or coercion – can one become good by doing good (although it is also possible to adjust one’s conduct under the law, not because it is legally prescribed but because it understands and identifies with the good that the legal norm pursues).

Public Morality, Deliberative Democracy and Freedom of Expression

The fundamental question concerning public morality is not whether it is possible or desirable for a society to have it or not to have it. In reality, society always has it and can never cease to have it. What is relevant, especially in a democratic society, is how and who should shape the values and principles that govern that society. In my view, the principal shapers of public ethics should be the citizens themselves. I think that in a free and plural democracy, the State should not be the primary agent shaping the fundamental values that underpin social coexistence, nor should the big business, media and financial groups. That is a fundamental requirement of deliberative democracy [29, 39, 40, 61–68].7 Otherwise, democracy becomes corrupted and turns into demagogy, quickly leading to an authoritarian or totalitarian regime. This process of democratic corruption is precluded when the political freedom of a community is based on the sum of individual freedoms, not in the abstract, but in their concrete and free exercise.

For that reason, citizens need to think for themselves, express their thoughts publicly in a climate of freedom – regardless of what they think – and contribute, within their means, to shaping the public ethics of the society in which they live. Furthermore, in a democracy, public ethics should be a dynamic reality, in constant movement, even when some of its parts have crystallized or have been enshrined in a legal norm. Therefore, the law should not prevent citizens from being able to think and express doctrines that are contrary to the hegemonic public ethics at a particular time. Hence, the importance of freedom of expression is that, although it is not the most important fundamental right (the right to life, for example, is the first and makes the exercise of the others possible), it is the most fundamental and genuine right in any democracy.

One could ask oneself the following questions: how can the dilemma between the exercise of individual freedom (in accordance with the personal ethics of the citizen) and the general character of the law (reflecting public ethics) be resolved? How can different ethics coexist in the same society, namely public ethics (principles more or less common to the majority and endorsed by law) and different private ethics (of each citizen)? To what extent, in a democratic regime can the State prohibit dissent or prevent a citizen from expressing their private morality when it is contrary to or different from public morality? This is, undoubtedly, a key question in any democracy worthy of the name. On the one hand, it is logical and understandable that the State should enact laws that reflect the prevailing public ethics of society at a given time. To do otherwise would be suspicious or worrying. Once the law has sanctioned some principle of public ethics, it is reasonable to prohibit conduct that violates it. However – and here comes the critical nuance – it is one thing to prohibit conduct contrary to fundamental values and quite another to prohibit opinion. The law should never prohibit the expression of dissenting opinions, as long as they do not constitute a severe and real threat to coexistence (encouraging hatred, violence, etc.) or a direct attack on the rights of third parties.

It should prohibit, however – in my opinion – dissenting expressions which have the effect of excluding, mocking and humiliating those who do not share any of the principles of a specific public morality should not be admissible, even if the law allows it in some cases. Let me put an example. If public morality, reflected in legislation, did not allow people to go into the street naked, they could be sanctioned, but a constitutional democracy should never punish those who, judging it a good thing to be able to go naked in the street – even if they were not legally allowed to do so – could at least express their opinion and defend – without the threat of any punishment – their dissenting stance; that is to say, support – for the free development of one’s own personality – the desirability of the citizen being able to go naked in the street or propose the creation of zones or urbanizations in which people could go naked in the street. The State should not deprive that person of the freedom to express what they think. In this fashion, freedom of expression would play its proper role in bridging the gap between ‘public morality’ and ‘private morality,’ promoting a constant ebb and flow between one morality and the other. This dynamism, characteristic of a genuinely free and pluralistic democracy, would prevent the totalitarian attitude of those who demand maximum freedom of expression when they claim their ideas for a new ‘public morality’ (think of May 68) and prohibit dissent when they have already succeeded in shaping a public morality following their ideas (which is what is currently happening with legislation on sexual freedom and gender identity) [6, 13, 19, 19–24, 52–54, 57, 59, 67, 69, 70–74].

Continuing with the previous example, if the day arrives in which nudism – being able to wander around the street naked – becomes part of public morality, should the State be allowed to prohibit the expression of dissent? Absolutely not; it should not be prohibited at all, and even less so – as is done with certain groups – by resorting to the principle of non-discriminatory freedom, with a line of argument as simplistic as the following: “if everyone can walk down the street as they wish, why discriminate against the nudist group? If you are not forced to go out naked, why do you seek to impose your position on everyone, preventing anyone from being able to go out naked? Why don’t you let others make their own moral choices?”. If one admits that the fundamental source and criterion of the principle of non-discriminatory freedom is of a strictly subjective order and does not take into account the good of the community as a whole – because one believes that this good does not exist, that the good is always something private, subjective and immanent –, the egalitarian or non-discriminatory argument can become, in the hands of the State, a dangerous tool of totalitarian imposition, which is incompatible with an authentic constitutional democracy.

The tendency to excessively restrict or entirely prohibit freedom of expression when talking about specific groups is another sign of the current fragility of exercising this fundamental right. Some argue that the mere dissenting expression about the ways of life of particular groups would constitute an incitement to hatred that, as such, should be criminalized. Although it may seem exaggerated, for them, it is not at all because they understand this discrepancy concerning some forms of life as an affront or offense to the group of people who shape their lives according to that model. As it is not possible to generalize this principle in all cases (because, if done, one could not disagree on almost anything), it starts from the ‘victimization’ of a group (based on the commission of civil and criminal offenses by some against those who belong to the group) to extend the criminalization of any discrepancy with respect to that group because it is considered hate speech. They lose sight, however, that this type of criminalization usually has a boomerang effect, which goes from one extreme to another, and rarely settles in the reasonable point of moderation that would imply punishing only those who inflict insults, humiliations or injuries, and not criminally prosecute the rest of society for expressing their views on any model of life, as happens with the discrepancy towards other groups, some of them much reviled over many years or even centuries. Of course, it seems more reasonable to punish those who insult and commit aggressions against a person (regardless of the group to which they belong) and to allow citizens to express their ideas about any way of life (whether or not they refer to a group of any kind – religious, professional, cultural, sexual, etc.) [69, 299–321].

Another symptom that demonstrates the poor quality or maturity of a democracy is the frequent use of labels or clichéd expressions to disqualify those who disagree (fascist, communist, fanatic, nationalist, pro-independence, philo-ethnic, homophobic, male chauvinist, far-right, far-left, etc.) This recourse, which is so frequent, especially in politics and the media, and which usually implies contempt or gross simplification of reality, does not seem to be the best way to promote freedom of expression and the spirit of dialogue that should characterize a constitutional democracy. Nevertheless, the problem for some is that they consider themselves so clear-headed and so entrenched in their ideological positions that they are unwilling to accept that, through dialogue and plural debate, consensus can be reached that is far removed from or alien to ‘their’ truth. When the majority supports their principles (they become public ethics), they prevent and prohibit dissent with the coercive force of laws and media pressure. However, when the majority does not share ‘their’ truth (private ethics), they promote disagreement in the name of freedom of expression and the right of minorities against the supposedly illegitimate impositions of the majority.

In summary, I argue that public morality should not be the result of the will of the State, nor of powerful lobbies (politicians, business people, media, and financial egalitarians), but the result of the exercise of the freedom of each and every citizen, who is called upon, to the extent of their possibilities, to shape the public ethics of their political community. In correspondence with what I have just stated, esteemed reader, I do not intend to convince you of anything, much less to convince you to think as I do. My purpose has been to freely express my critical reflections on a vital issue in any democratic society, and in ours in particular, in the hope of helping you to think for yourself and to encourage you to also have the courage to contribute, through your free and active participation, to the flourishing of a freer, more open, plural and mature democracy.

Democracy, Freedom of Expression and Right to Dissent

There is no democracy without freedom of expression, and this is only real if there is room for different, minority, or dissenting thoughts. Since this is the essence of democracy, dissent is essential in a democracy [23, 848–852]. Rejecting dissent would lead to the end of deliberative democracy [20, 75]. “Rule of majority is an integral part of democracy, but majoritarianism is the antithesis of democracy” [76].

Nobody would deny that dialogue and tolerance are critical to a pluralistic and inclusive democracy. However, few see dissent in a positive light, and even fewer are willing to accept it and engage in dialogue with it. Today’s culture is based on the idea that “the enemy is the other, the stranger” (Meinecke), that “hell is the other” whose gaze and judgment limit me, expose my limitation, humiliate me, not being able to escape from that judgment of others in the knowledge of myself (Sartre) [77]. Hence, the other can – and perhaps, must – be endured if their ideas and opinions are identical or similar to mine. If they are different but at least able to remain silent, their presence in society is still bearable and tolerable. Nonetheless, if one dares to disagree, to give reasons that may contribute to public deliberation, they should be silenced immediately. The dissenters are those who cross this line and dare to express their opinion publicly (alien or contrary to the majority), and this makes them a persona non grata and an enemy, thereby acquiring a new social – and, in part, also legal – vulnerable status because their rights happen to be more those of a law of war than those of a state governed by the rule of law.

It is paradoxical that today’s culture, so diverse and inclusive in theory, is hardly so in reality with relation to dissenting opinion. A US journalist based in Poland, Anne Applebaum, has just testified to this in a recently published book that has become a best-seller [36]. Applebaum experienced the consequences of expressing one’s own ideas, both in politics and society, to the point of being abandoned by educated people she had considered good friends. She also recounts how Western democracies are being besieged by authoritarianism that penetrates society with simple, false – or half-false – and radical messages, but which are attractive and have an effect. But reality is not reducible to simple messages, and simplistic approaches often contain falsehoods or half-truths on which the authoritarian mentality feeds. Political psychologist Karen Stenner argues that those who want to impose their own way of seeing reality do not tolerate complexity, nor do they wish to understand that certain events are rooted in a variety of factors [36].

Dissent is seen as something annoying and unpleasant which is to be stoically endured, but not as an essential means of enriching one’s own thinking, let alone as a requirement for public deliberation of what is suitable for each society. Hence the title of Arthur C. Brooks’ book: Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America from our Culture of Contempt [42]. For Brooks, society will be saved by those who can love their enemies, not by those who indulge in a culture of contempt for their enemies, i.e., those who disagree, those who think differently.