Forgotten audio formats: Wire recording

From espionage to home recording, the colorful life of the longest-used audio medium.

It’s bizarre but true: wire recording is the longest-lasting capture format in audio history, one that paved the way for reel-to-reel tapes and a host of others—even though most people today, and some techies included, have barely heard of it.

Invented way back in 1898 and patented two years later, wire recording was somehow still getting some limited use as late as the early 1970s, while rockets took man to the moon on an annual basis. In its wake, vinyl, with its 67 years, and CD with a mere 33, look like footling youngsters. In its none-too-brief life, “the wire” also found use in Hollywood, provided a broadcast aid to spying, helped launch digital data capture, and pioneered the new art of bootlegging—sorry, “home recording.”

Wire was longer-lasting in other ways, too—whereas shellac and vinyl records would only last a few minutes per side, and the first commercial tape decks weren’t that much better, the wire recorder could get down over 60 minutes of audio.

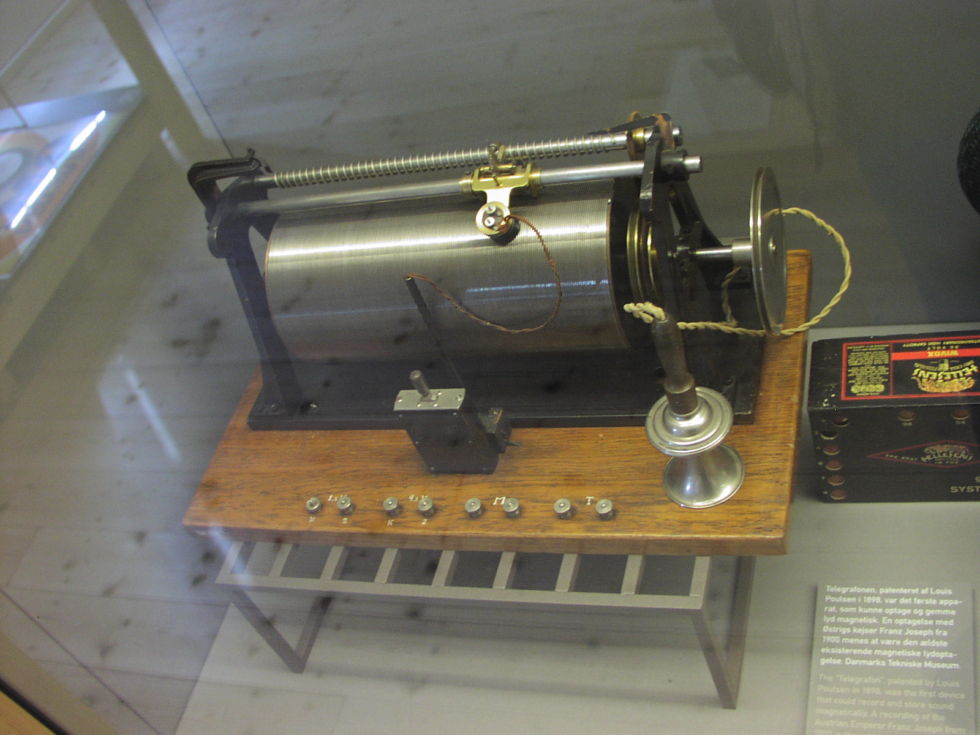

Hanging on the telegraphone

Of course, it didn’t start that way. The earliest wire device was cooked up at the end of the 19th century by one Valdemar Poulsen, a Danish-American inventor who, five years later, developed the first continuous-wave radio transmitter. This first “telegraphone,” as Poulsen dubbed it, was somewhat crude, but it did have the key conceptual elements: a metal wire was pulled between spools across a recording head, which magnetised the wire in accordance with the sound signal it was receiving at that moment. In other words it recorded recognisable sound.

- Dates

- 1898 – early 1960s

- Common Size(s)

- Wire: up to 7200ft

- Reels: 2 3/4″ to 3 3/4″ (diameter); 3/4″ to 1 1/4″ (thickness)

- Description

- Wire recording is a recorded sound format made of magnetized recording-grade steel or stainless steel wire. The wire is wound around a plastic or metal spool and can be virtually any length.

- Composition

- Magnetized steel or stainless steel wire wound around a plastic or metal spool

- Deterioration

- One of the most common issues with wire recordings is tangled wire. The wire is extremely thin (approximately .004 inches thick); it can easily wrap around itself, become tangled, and possibly break. This problem is an annoyance but can be relatively simple to resolve—the wire just needs to be untangled and rewound onto the reel. Breaks in the wire can be repaired by knotting the two ends of the wire together. Since wire travels at a high transport speed, the knot will be a minor sonic disturbance during playback.

Although the wire is generally composed of recording-grade stainless steel, some recordings prior to World War II were made on steel wire, which is prone to rust. While occurrences of rust are typically rare, they can impede signal retrieval or weaken the already thin wire and cause the wire to break during handling or playback.

Signal print-through can also be an issue. Print-through occurs when the magnetized signal from one section of the wire migrates to lower sections and leaves a sonic imprint. Print-through is often identifiable when a faint pre- or post-echo is heard during playback. Storing the wire in a tails-out manner (i.e. with the end of the wire on the outermost layer of the spool) can aid in minimizing some of the sonic disturbance. Storing the wire tails-out minimizes pre-echo, which is often more annoying than post-echo. Storing the wire tails-out, however, does not prevent print-through from occurring.

- Risk Level

- Wire recording media and equipment are long obsolete. Based on the content, it should be considered a high priority for reformatting.

- Playback

- Wire can tangle and break, especially during playback. It is thin and, depending upon the material, can be susceptible to rust. Any surface abrasion or contaminant can wear down the playback heads on a wire recording. Additionally, playback equipment is difficult to find. Preservation playback and reformatting may be handled best by a vendor who has experience with handling this format.

- Background

- Wire recording was the first magnetic media recording technology. It was developed by Vlademar Poulsen in 1898 and was in popular use until the late 1940s, when magnetic tape emerged as the choice home and dictation recording medium. However, wire continued to be used as a home recording and dictation format in military, commercial, and office environments as late as the early 1960s.

- Storage Environment

- Allowable Fluctuation: ±2°F; ±5% RH

Ideal Acceptable Temp. 40–54°F (4.5–12°C) 33–44°F (0–6.5°C) RH 30–50% RH - Storage Enclosure(s)

- Remove the wire recordings from their original cardboard containers, which are subject to mold infestation and do not protect the recordings from moisture. Storing the recordings in a protective plastic container or archival quality paperboard enclosure is recommended.

- Storage Orientation

- Secure the wire around the reel so that it does not become loose and tangle. Either unrecorded stainless steel wire or plastic can be used as leader. Although storing wires in the “tails out” position lessens the effects of print-through, this may not be practical due to the scarcity of wire recording equipment and the risk involved in mounting the wire on the playback equipment. Wood cabinets should be avoided. Enameled steel, stainless steel, or anodized aluminum are preferred.

- Handling and Care

- Keep magnetic media away from stray electromagnetic fields and avoid devices with a motor or transformer, both of which generate an alternating magnetic field. Never leave media in a playback machine; always return to storage enclosure when not in use. source

Wire Recording Speaks Again

If you think of old recording technology, you probably think of magnetic tape, either in some kind of cassette or, maybe, on reels. But there’s an even older technology that recorded voice on hair-thin stainless steel wire and [Mr. Carlson] happened upon a recorded reel of wire. Can he extract the audio from it? Of course! You can see and hear the results in the video below.

It didn’t hurt that he had several junk wire recorders handy, although he thought none were working. It was still a good place to start since the heads and the feed are unusual to wire recorders. Since the recorder needed a little work, we also got a nice teardown of that old device. The machine was missing belts, but some rubber bands filled in for a short-term fix.

The tape head has to move to keep the wire spooled properly, and even with no audio, it is fun to watch the mechanism spin both reels and move up and down. But after probing the internal pieces, it turns out there actually was some audio, it just wasn’t making it to the speakers.

The audio was noisy and not the best reproduction, but not bad for a broken recorder that is probably at least 80 years old. We hope he takes the time to fully fix the old beast later, but for now, he did manage to hear what was “on the wire,” even though that has a totally different meaning than it usually does.

It is difficult to recover wire recordings, just as it will be difficult to read modern media one day. If you want to dive deep into the technology, we can help with that, too.