Frank C Brito – An American Hero, A Family Hero and one of the Teddy Roosevelt’s RoughRiders

An American Hero, an American Indian, an American Patriot and local Hero from Las Cruces New Mexico

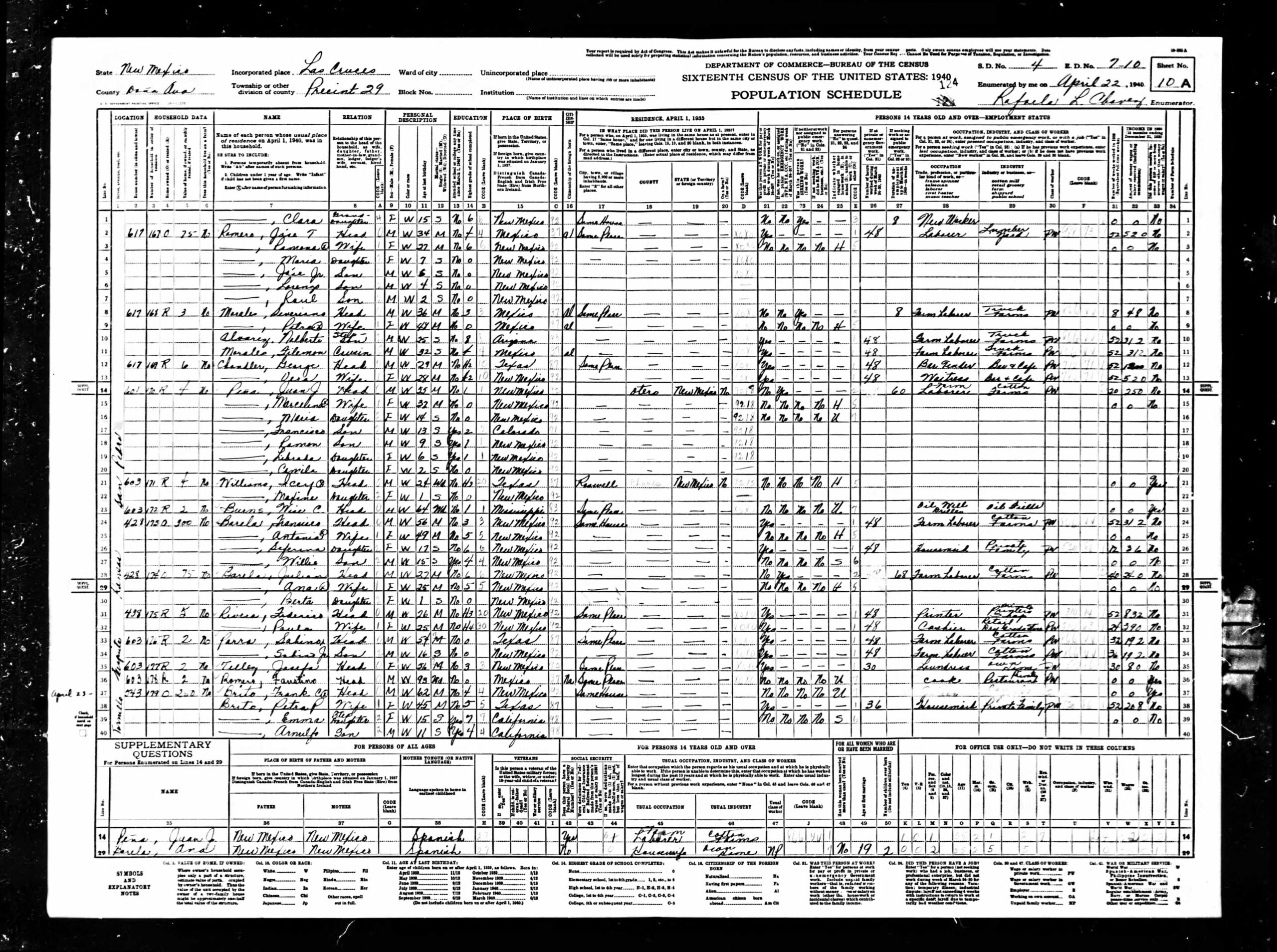

Frank C Brito in the 1940 Census

| Age | 62, born abt 1878 | |

| Birthplace | New Mexico | |

| Gender | Male | |

| Race | White | |

| Home in 1940 |

543 Tornillo

Las Cruces, Dona Ana, New Mexico |

|

| Household Members | Age | |

| Head | Frank C Brito | 62 |

| Wife | Petra P Brito | 45 |

| Stepdaughter | Emma Brito | 15 |

| Son | Armulfo Brito | 11 |

Rough Rider Frank Brito one ‘Tough Hombre’

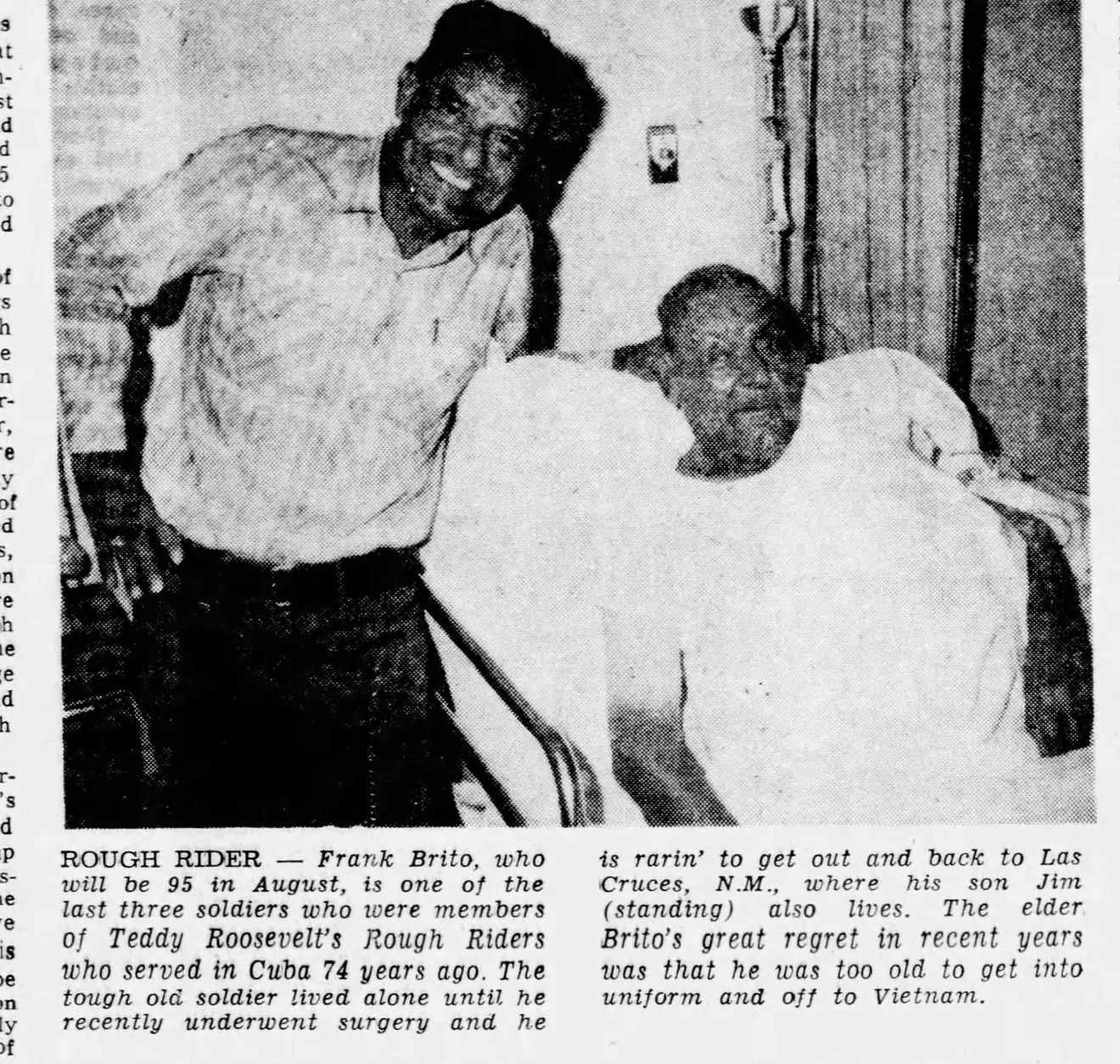

On July 16, 1972, Art Leibson told the story of Frank Brito who, at the time, was one of three surviving members of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders:

Frank Brito who admits what his record proves — that he is one tough hombre — underwent major surgery last week in a local hospital and expects to be fully recovered by Aug. 24 when he will be 95 years old. And he expects to go right on living alone and liking it.

Brito’s spirit indomitable

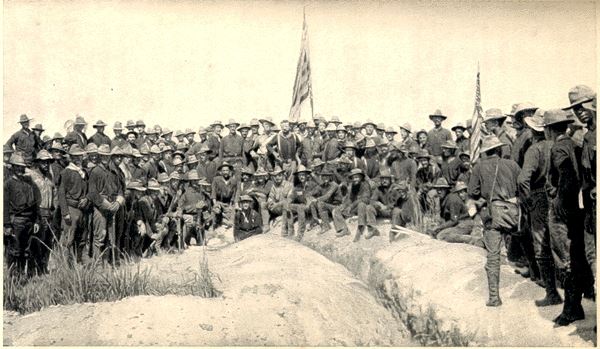

Brito has the distinction of being one of three survivors of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders who stormed Kettle Hill in the battle for San Juan Hill in the Spanish-American War. When Dale walker, who combines folklore research with his publicity duties at the University of Texas at El Paso, discovered Brito living in Las Cruces, N.M., he wrote an article on the old soldier saying there was only one other Rough Rider still living. Since then he learned that a Dr. George Hammer, living in Florida and 99 last May, also rode with Roosevelt.

His eyes are dim, his hearing almost gone, but Brito’s spirit is indomitable. He lived alone in Las Cruces, right up to the time he entered the hospital for surgery, ignoring the please of his children to live with them. He did most of his own cooking, in a small adobe home, his only recreation being his radio. He largely ignored a TV set because of his eyesight.

A daughter, Mrs. Ramon Mendoza, of El Paso, is hopeful that her father will finally admit he can use help and move in with her when he eves the hospital.

Brito is the son of a Yaqui Indian prospector an as born in 1877 at Pinos Altos, N.M., then a mining boomtown. As Walker pointed out in his account of his career, he was born the year following Custer’s Last stand at Little Big Horn. Rutherford B. Hayes was President. source

Spanish American War Regiments

New Mexico in the Spanish American War, 1898

New Mexico’s part in the Civil war, when the Territory was very young and its citizens and its interests less thoroughly American than now, is only dimmed by the lustre shed on her military annals by the performance of her sons in the war with Spain. The deeds of the famous regiment of “Rough Riders.” to which New Mexico furnished a large share of volunteers, will be a cherished heritage to the Southwest as long as men are stirred to enthusiasm by the exploits of war.

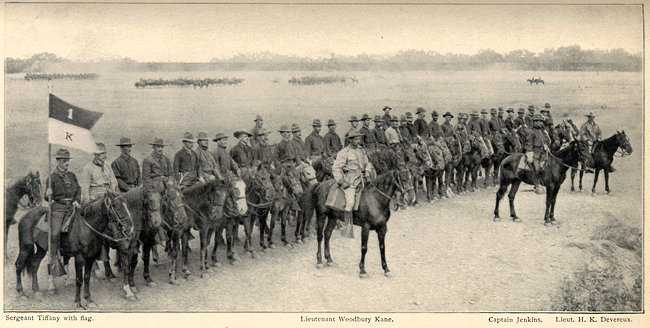

At the opening of the Spanish-American war, in 1898, Congress authorized the raising of three cavalry regiments from among the rough riders and riflemen of the Rockies and the Great Plains. The command popularly known as the “Rough Riders” the First United States Volunteer Cavalry, was recruited principally from these western states, and the mustering places for the regiment were appointed in New Mexico, Arizona. Oklahoma and Indian Territory. Before the detailed work of organization was begun. Dr. Leonard Wood was commissioned colonel, and Theodore Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of war, lieutenant-colonel of the regiment.

Within a day or two after it was announced that such a unique command was to be organized, the commanding officers were deluged with applications from every part of the country. While the only organized Bodies they were at liberty to accept were those from the four territories, the raising of the original allotment of seven hundred and eighty to one thousand men allowed them to enroll the names of individual applicants from various other sources, from universities, aristocratic social clubs and from men in whose veins flowed some of the most ancient blood in America.

The regiment gathered and was organized at San Antonio, Texas. The bulk of the regiment was made up of men who came from New Mexico, Arizona. Oklahoma and Indian Territory. “They were a splendid set of men, these southwesterners,” wrote Colonel Roosevelt, “tall and sinewy, with resolute, weather-beaten faces, and eyes that looked a man straight in the face without flinching. They included in their ranks men of every occupation: but the three types were those of the cowboy, the hunter and the mining prospector, the man who wandered hither and thither, killing game for a living, and spending his life in the quest for metal wealth. In all the world there could be no better material for soldiers than that afforded by these grim hunters of the mountains, these wild rough riders of the plains. They were accustomed to handling wild and savage horses; they were accustomed to following the chase with the rifle, both for sport and as a means of livelihood. Varied though their occupations had been, almost all had, at one time or another, herded cattle and hunted big game. They were hardened to life in the open, and to shifting for themselves under adverse circumstances. They were used, for all their lawless freedom, to the rough discipline of the round-up and the mining company. Some of them came from the small frontier towns; but most were from the wilderness, having left their lonely hunters’ cabins and shifting cow-camps to seek new and more stirring adventures beyond the sea.

“They had their natural leaders, the men who had shown they could master other men, and could more than hold their own in the eager, driving life of the new settlements.

“The captains and lieutenants were sometimes men who had campaigned in the regular army against Apache, Ute and Cheyenne, and who, on completing their service, had shown their energy by settling in the new communities and growing up to be men of mark. In other cases they were sheriffs, marshals, deputy sheriffs and deputy marshals, men who had fought Indians, and still more often had fought relentless war upon the lands of white desperadoes.” There was Captain Llewellyn, of New Mexico, a good citizen, a political leader, and one of the most noted peace officers of the country; he had been shot four times in pitched fights with red marauders and white outlaws. There was Lieutenant Ballard, who had broken up the Black-jack gang of ill-omened notoriety, and his captain, Curry, another New Mexican sheriff of fame. All easterners and westerners, northerners and southerners, officers and men, cowboys and college graduates, wherever they came from, and whatever their social position, possessed in common the traits of hardihood and a thirst for adventure. They were to a man born adventurers, in the old sense of the word.”

On Sunday, May 29, the regiment broke camp and proceeded by rail to Tampa, Fla., the trip consuming four days. On the morning of June 14 the troops proceeded, on board the transport Yucatan, for Cuba. For six days the thirty or more transports which had left Tampa steamed steadily southwestward, under the escort of battleships, cruisers and torpedo boats. On the morning of June 22 the troops began disembarking at Daiquiri, a small port near Santiago de Cuba, after this and other nearby points had been shelled to dislodge any Spaniards who might be lurking in the vicinity.

Before leaving Tampa the Rough Riders had been brigaded with the First (white) and Tenth (colored) Regular Cavalry under Brigadier-General S. B. M. Young, as the Second Brigade, which, with the First Brigade, formed a cavalry division placed in command of Major-General Joseph Wheeler. The afternoon following their landing they were ordered forward through the narrow, hilly jungle trail, arriving after nightfall at Siboney.

Before the tired soldiers (men who had been accustomed to traveling on horseback all their lives, for the most part, but now compelled to proceed on foot) could recuperate, the order to proceed against the Spanish position was given, and the first actual fighting was on. This was on Tune 24. During the advance against the Spanish outposts Henry J. Haefner, of Troop G., fell, mortally wounded. This was the first casualty in action. Haefner enlisted from Gallup, New Mexico. He fell without uttering a sound, and two of his companions dragged him behind a tree. Here he propped himself up and asked for his canteen and his rifle, which Colonel Roosevelt handed to him. He then began loading and firing, which he continued until the line moved forward. After the fight he was found dead.

After driving the enemy from their position at the American right a temporary hill followed. Fighting between the Spanish outposts and the American line was soon resumed, however. A perfect hail of bullets swept over the advancing line, but most of them went high. After a quick charge the enemy abandoned their main position in the skirmish line. The loss to the Rough Riders was eight men killed and thirty-four wounded; the First Cavalry lost seven men killed and eight wounded; the Tenth Cavalry lost one man killed and ten wounded. The Spaniards were under General Rubin. This fight, the first on Cuban soil, is officially known as the Battle of Las Guasimas.

On the afternoon of June 25 the regiment moved forward about two miles and camped for several days. In the meantime General Young was stricken with the fever. Colonel Wood then took command of the brigade, leaving Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt in command of the regiment. On June 30 orders were received to be prepared to march against Santiago. It was not until the middle of the afternoon that the regiment took its position in the marching army, and eight o’clock that night when they halted on El Paso hill. Word ^vent forth that the main fighting was to be done by Lawton’s infantry, which was to take El Caney, several miles to the right, while the Rough Riders were simply to make a diversion with the artillery.

About six o’clock the next morning, July 1, the fighting began at El Caney. As throughout the entire campaign, the enemy used smokeless powder, which rendered the detection of their location well-nigh impossible. Soon after the beginning of the artillery engagement. Colonel Roosevelt was ordered to march his command to the right and connect with Lawton, an order impossible to obey. A captive balloon was in the air at the time. As the men started to cross a ford, the balloon, to the horror of everybody, began to settle at the exact front of fording. It was a special target for the enemy’s fire, but the regiment crossed before it reached the ground. There it partly collapsed and remained, causing severe loss of life, as it indicated the exact point at which other troops were crossing.

The heat was intense, and many of the men began to show signs of exhaustion early in the day. The Mauser bullets drove in sheets through the trees and jungle grass. The bulk of the Spanish fire appeared to be practically un-aimed, but the enemy swept the entire field of battle. Though the troopers were scattered out far apart, taking advantage of every scrap of cover, man after man fell dead or wounded. Soon the order came to move forward and support the regulars in the assault on the hills in front. Waving his hat aloft. Colonel Roosevelt shouted the command to charge the hill on the right front. At about the same moment the other officers gave similar orders, and the exciting rush up ‘Kettle hill” began. The first guidons planted on the summit of the hill, according to Roosevelt’s account, were those of Troops G, E and F of his regiment, under their captains, Llewellyn, Luna and Muller.

No sooner were the Americans on the crest of the hill than the Spaniards, from their strong entrenchments on the hills in front, opened a heavy fire, with rifles and artillery. Our troops then began volley firing against the San Juan block-house and the surrounding trenches. As the regulars advanced in their final assault and the enemy began running from the rifle pits, the Rough Riders were ordered to cease firing and charge the next line of trenches, on the hills in front, from which they had been undergoing severe punishment. Thinking that his men naturally would follow. Colonel Roosevelt jumped over the wire fence in front and started rapidly up the hill. But the troopers were so excited that they did not hear or heed him. After leading on about a hundred yards with but five men, he returned and chided his men for having failed to follow him.

“We did not hear you. Colonel,” cried some of the men. “We didn’t see you go. Lead on, now; we’ll sure follow you.”

The other regiments joined the Rough Riders in the historic charge which followed. But long before they could reach the Spaniards the latter ran, excepting a few who either surrendered or were shot down. When the attacking force reached the trenches they found them filled with dead bodies. There were few wounded. Most of the fallen had bullet holes in their heads which told of the accurate aim of the American sharpshooters. “There was great confusion at this time,” writes Colonel Roosevelt, “the different regiments being completely intermingled, white regulars, colored regulars, and Rough Riders. We were still under a heavy fire and I got together a mixed lot of men and pushed on from the trenches and ranch houses which we had just taken, driving the Spaniards through a line of palm trees, and over the crest of a chain of hills. When we reached these crests we found ourselves overlooking Santiago.”

Here Colonel Roosevelt was ordered to advance no further, but to hold the hill at all hazards. With his own command were all the fragments of the other five cavalry regiments at the extreme right. The Spaniards had fallen back upon their supports, and our troops were still under a very heavy fire from rifles and artillery. Our artillery made one or two efforts to come into action on the infantry firing line, but their black powder rendered each attempt fruitless. In the course of the afternoon the Spaniards made an unsuccessful attempt to retake the hill. A few seconds’ firing stopped their advance and drove them into cover of the trenches.

The troops slept that night on the hill-top, being attacked but once before daybreak, about 3 A. M. and then for a short time only. At dawn the attack was renewed in earnest. The Spaniards fought more stubbornly than at Las Guasimas, but their ranks broke when the Americans charged home.

In the attack on the San Juan hills our forces numbered about sixty-six hundred. The Spanish force numbered about forty-five hundred. Our total loss in killed and wounded was one thousand and seventy-one.

The fighting continued July 2, but most of the Spanish firing proved harmless. During the day our force in the trenches was increased to about eleven thousand, and the Spaniards in Santiago to upwards of nine thousand. As the day wore on the fight, though raging fitfully at intervals, gradually died away. The Spanish guerrillas caused our troops much trouble, however. They were located, usually, in the tops of trees, and as they used smokeless powder it was almost impossible to locate and dislodge them. These guerrillas showed not only courage, but great cruelty and barbarity. They seemed to prefer for their victims the unarmed attendants, the surgeons, the chaplains and hospital stewards. They fired at the men who were bearing off the wounded in litters, at the doctors who came to the front and at the chaplains who held burial service.

The firing was energetically resumed on the morning of the 3rd, but during the day the only loss to the Rough Riders was one man wounded. At noon the order to stop tiring was given, and a flag of truce was sent in to demand the surrender of the city. For a week following peace negotiations dragged along. Failing of success, fighting was resumed shortly after noon of the loth, but it soon became evident that the Spaniards did not have much heart in their work. About the only Rough Riders who had a chance for active work were the men with the Colt automatic guns and twenty picked sharpshooters who were on the watch for guerrillas. At noon, on the nth, the Rough Riders, with one of the Gatlings, were sent over to the right to guard the Caney road. But no fighting was necessary, for the last straggling shot had been fired by the time they arrived.

On the 17th the city formally surrendered. Two days later the entire division was marched back to the foothills west of El Caney, where it went into camp with the artillery. Here many of the officers and men became ill, and as a rule less than fifty present were fit for any kind of work. All clothing was in rags; even the officers had neither socks nor underwear. The authorities at Washington, misled by reports received from some of their military and medical advisers at the front, became panic-stricken and hesitated to bring the army home, lest it might import yellow fever into the United States. The real foe, however, was not yellow fever, but malarial fever. The awful conditions surrounding the army finally led to the writing of the historic “round robin,” in which the leading officers in Cuba showed that to keep the army in Santiago meant its complete and objectless ruin. The result was immediate. Within three days orders came to put the army in readiness to sail for home. August 6 the order came to embark, and the next morning the Rough Riders sailed on the transport Miami which reached Montauk point, the east end of Long Island, New York, on the afternoon of the 14th. The following day the troops disembarked and went into camp at Camp Wyckoff. The regiment remained here until September 15, when its members received their discharges and returned to civil life.

Teddy Roosevelt & The Rough Riders of 1898

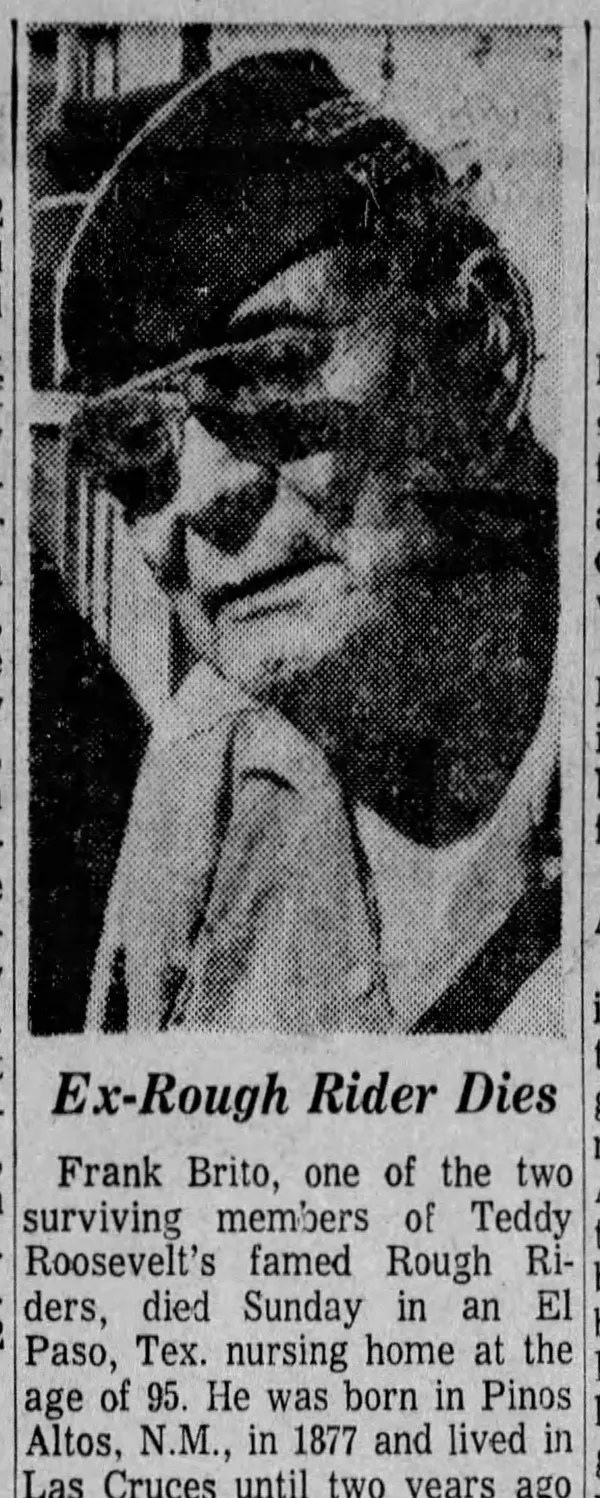

The last two surviving veterans of the regiment were Frank C. Brito and Jesse Langdon. Brito, from Las Cruces, New Mexico, whose father was a Yaqui Indian

|

The Rough Riders is the name bestowed on the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, one of three such regiments raised in 1898 for the Spanish-American War and the only one of the three to see action. The United States Army was weakened and left with little manpower after the American Civil War roughly thirty years prior. As a result, President William McKinley called upon 1,250 volunteers to assist in the war efforts. It was also called “Wood’s Weary Walkers” after its first commander, Colonel Leonard Wood, as an acknowledgment of the fact that despite being a cavalry unit they ended up fighting on foot as infantry. Wood’s second in command was former assistant secretary of the United States Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, a man who had pushed for American involvement in Cuban independence. When Colonel Wood became commander of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, the Rough Riders then became “Roosevelt’s Rough Riders.” That term was familiar in 1898, from Buffalo Bill who called his famous western show “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World.” The Rough Riders were mostly made of college athletes, cowboys, and ranchers. The volunteers were gathered in four areas: Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas. They were gathered mainly from the southwest because the hot climate region that the men were used to was similar to that of Cuba where they would be fighting. “The difficulty in organizing was not in selecting, but in rejecting men.” The allowed limit set for the volunteer cavalry men was promptly met. They gathered a diverse bunch of men consisting of cowboys, gold or mining prospectors, hunters, gamblers, Native Americans and college boys; all of whom were able-bodied and capable on horseback and in shooting. Among these men were also police officers and military veterans who wished to see action again. Men who had served in the regular army during campaigns against Indians or served in the Civil War had been gathered to serve as higher ranking officers in the cavalry. In this regard they possessed the knowledge and experience to lead and train the men well. As a whole, the unit would not be entirely inexperienced. Leonard Wood, a doctor who served as the medical adviser for both the President and secretary of war, was appointed the position of Colonel of The Rough Riders with Roosevelt serving as Lieutenant Colonel. One particularly famous spot where volunteers were gathered was in San Antonio, Texas, at the Menger Hotel Bar. The bar is still open and serves as a tribute to the Rough Riders, containing much of their, and Theodore Roosevelt’s, uniforms and memorabilia. Before training began, Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt used his political influence gained as Assistant Secretary of the Navy to ensure that his volunteer cavalry regiment would be properly equipped to serve as any regular unit of the U.S. Army. For private soldiers and non commissioned officers, this meant the M1892/98 Springfield (Krag) bolt action rifle in .30 Army (.30-40) caliber: “They succeeded in getting their cartridges, revolvers (Colt .45), clothing, shelter-tents, and horse gear … and in getting the regiment armed with the Krag-Jorgensen carbine used by the regular cavalry.” Officers of the regiment each received a new lever-action M1895 Winchester rifle, also in .30 Army. The Rough Riders also used Bowie Hunter knives. A last minute gift from a wealthy donor were a pair of modern tripod mounted, gas-operated M1895 Colt-Browning machine guns in 7mm Mauser caliber. In contrast, the uniforms of the regiment were designed to set the unit apart: “The Rough Rider uniform was a slouch hat, blue flannel shirt, brown trousers, leggings, and boots, with handkerchiefs knotted loosely around their necks. They looked exactly as a body of cowboy cavalry should look.” It was the ‘rough and tumble’ appearance and charisma that contributed to earning them the title of The Rough Riders. Training was very standard, even for a cavalry unit. They worked on basic military drills, protocol, and habits involving conduct, obedience and etiquette. The men proved to be eager to learn what was necessary and the training went smoothly. It was decided that the men would not be trained to use the saber as other cavalries often used, because they had no prior experience with that combat skill. Instead, they chose to have the men stick to the use of their carbines and revolvers as primary and secondary weapons. Although the men, for the most part, were already experienced horsemen, the officers refined their techniques in riding, shooting from horseback, and practicing in formations and in skirmishes. Along with this the high-ranking men heavily studied books filled with tactics and drills to better themselves in leading the others. During times which physical drills could not be run, either because of confinement on board the train, ship, or during times where space was inadequate, there were some books that were read further as to leave no time wasted in preparation for war. The competent training that the volunteer men received prepared them best as possible for their duty. They were not simply handed weapons and given vague directions to engage in a disorderly brawl. On May 29, 1,060 Rough Riders and 1,258 of their horses and mules made their way to the Southern Pacific railroad to travel to Tampa, Florida where they would set off for Cuba. The lot awaited orders for departure from Major General William Rufus Shafter. Under heavy prompting from Washington D.C., General Shafter gave the order to dispatch the troops early before sufficient traveling storage was available. Due to this problem, only eight of the twelve companies of The Rough Riders were permitted to leave Tampa to engage in the war, and many of the horses and mules were left behind. Aside from Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt’s first hand mention of deep, heartfelt sorrow from the men left behind, this situation resulted in a premature weakening of the men. Approximately one fourth of them who received training had already been lost, most dying of malaria and yellow fever. This sent the remaining troops into Cuba with a significant loss in men and morale. Upon arrival on Cuban shores on June 23 the men promptly unloaded themselves and the small amount of equipment they carried with them. Camp was set up nearby and the men were to remain there until further orders had been given to advance. Further supplies were unloaded from the ships over the next day including the very few horses that were allowed on the journey. “The great shortcoming throughout the campaign was the utterly inadequate transportation. If they had been allowed to take our mule-train, they could have kept the whole cavalry division supplied.” Each man was only able to carry a few days worth of food which had to last them longer and fuel their bodies for rigorous tasks. Even after only seventy-five percent of the total number of cavalry men was allowed to embark into Cuba they were still without most all of the horses that they had so heavily been trained and accustomed to using. They were not trained as infantry and were not conditioned to doing heavy marching, especially long distance in hot, humid, and dense jungle conditions. This ultimately served as a severe disadvantage to the men who had yet to see combat. Within another day of camp being established, men were sent forward into the jungle for reconnaissance purposes, and before too long they returned with news of a Spanish outpost, Las Guasimas. By afternoon, The Rough Riders were given the command to begin marching towards Las Guasimas, to eliminate opposition and secure the area which stood in the path of further military advance. Upon arrival at their relative destination, the men slept through the night in a crude encampment nearby the Spanish outpost they would attack early the next morning. The enemy held an advantage over the Americans by knowing their way through the complicated trails in the area of combat. They predicted where the Americans would be traveling on foot and exactly what positions to fire on. They also were able to use the land and cover in such a way that they were difficult to spot. Along with this, their guns used smokeless powder which did not give away their immediate position upon firing as other gunpowders would have. This increased the difficulty of finding the opposition for the U.S. soldiers. In some locations the jungle was too thick to see very far. General Young, who was in command of the regulars and cavalry, began the attack in the early morning. Using long-range, large-caliber Hotchkiss guns he fired at the opposition, who were reportedly concealed along trenches, roads, ridges, and jungle cover. Colonel Wood’s men, accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt, were not yet in the same vicinity as the other men at the start of the battle. They had a more difficult path to travel around the time the battle began, and at first they had to make their way up a very steep hill. “Many of the men, footsore and weary from their march of the preceding day, found the pace up this hill too hard, and either dropped their bundles or fell out of line, with the result that we went into action with less than five hundred men.” Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt became aware that there were countless opportunities for any man to fall out of formation and resign from battle without notice as the jungle was often too thick in places to see through. This was yet another event that left the group with fewer men than they had at the start. Regardless, The Rough Riders pushed forward towards the outpost along with the regulars. Using careful observation, the officers were able to locate where the opposition was hidden in the brush and entrenchments and they were able to target their men properly to overcome them. Towards the end of the battle, Edward Marshall, a newspaper writer, was inspired by the men around him in the heat of battle to pick up a rifle and begin fighting alongside them. When he suffered a gunshot wound in the spine from one of the Spaniards another soldier mistook him as Colonel Wood from afar and ran back from the front line to report his death. Due to this misconception, Roosevelt temporarily took command as Colonel and gathered the troops together with his leadership charisma. The battle lasted an hour and a half from beginning to end with The Rough Riders suffering 8 dead and 31 wounded, including Captain Allyn K. Capron, Jr. Roosevelt came across Colonel Wood in full health after the battle finished and stepped down from his position to Lieutenant Colonel. The United States had full control of this Spanish outpost on the road to Santiago by the end of the battle. General Shafter had the men hold position for six days while additional supplies were brought ashore. During this time The Rough Riders ate, slept, cared for the wounded, and buried the dead from both sides. During the six day encampment, some men died from fever. Among those stricken by illness was General Joseph Wheeler. Brigadier General Samuel Sumner assumed command of the cavalry and Wood took the second brigade as Brigadier General. This left Roosevelt as Colonel of The Rough Riders. The order was given for the men to march the eight miles along the road to Santiago from the outpost they had been holding. Originally, Colonel Roosevelt had no specific orders for himself and his men. They were simply to march to San Juan Heights where over one-thousand Spanish soldiers held the area and hold position. It was decided that Brigadier General Henry Lawton’s division would be the main fighters in the battle while taking El Caney, a Spanish stronghold, a few miles away. The cavalry was to simply serve as a distraction while artillery and battery struck the Spanish from afar. Lawton’s infantry would begin the battle and The Rough Riders were to march and meet with them mid-battle. In this way, The Rough Riders were not seen as a critical tool to the United States Army in this battle. San Juan Hill and another hill were separated by a small valley and pond; the river ran near the foot of both. Together, this geography formed San Juan Heights. Colonel Roosevelt and The Rough Riders made their way to the foot of what was dubbed Kettle Hill because of the old sugar refinement cauldrons that lay along it. The battle of San Juan Heights began with the firing of the artillery and battery at the enemy location. Soon after battery-fire was returned and The Rough Riders, standing at the position of the friendly artillery, had to promptly move to avoid shells. The men moved down from their position and began making their way through and along the San Juan River towards the base of Kettle Hill. There they took cover along the riverbank and in the tall grass to avoid sniper and artillery fire that was being directed towards their position, however they were left vulnerable and pinned down. The Spanish rifles were able to discharge eight rounds in the twenty seconds it took for the United States rifles to fire one round. In this way they had a strong advantage over the Americans. The rounds they fired were 7mm Mauser bullets which moved at a high velocity and inflicted small, clean wounds. Some of the men were hit, but few were mortally wounded or killed. Colonel Roosevelt, deeply dissatisfied with General Shafter’s inaction with sending men out for reconnaissance and failure to issue more direct orders, became uneasy with the idea of leaving himself and his men sitting in the line of fire. He sent messengers to seek out one of the generals to try to coax orders from them to advance from their position. Finally, the Rough Riders received orders to assist the regulars in their assault on the hill’s front. Roosevelt, riding on horseback, got his men onto their feet and into position to begin making their way up the hill. He claimed that he wished to fight on foot as he did at Las Guasimas; however he would have found it difficult to move up and down the hill to supervise his men in a quick and efficient manner on foot. He also recognized that he could see his men better from the elevated horseback, and they could see him better as well. Roosevelt chided his own men to not leave him alone in a charge up the hill, and drawing his sidearm promised nearby black soldiers separated from their own units that he would fire at them if they turned back, warning them he kept his promises. His Rough Riders chanted (likely in jest) “Oh he always does, he always does!” The soldiers, laughing, fell in with the volunteers to prepare for the assault. As the troops of the various units began slowly creeping up the hill, firing their rifles at the opposition as they climbed, Roosevelt went to the captain of the platoons in back and had a word with him. He stated that it was his opinion that they could not effectively take the hill due to an insufficient ability to effectively return fire, and that the solution was to charge it full-on. The captain reiterated his colonel’s orders to hold position. Roosevelt, recognizing the absence of the other Colonel, declared himself the ranking officer and ordered a charge up Kettle Hill. The captain stood hesitant, and Colonel Roosevelt rode off on his horse, Texas, leading his own men uphill while waving his hat in the air and cheering. The Rough Riders followed him with enthusiasm and obedience without hesitation. By then, the other men from the different units on the hill became stirred by this event and began bolting up the hill alongside their countrymen. The ‘charge’ was actually a series of short rushes by mixed groups of regulars and Rough Riders. Within twenty minutes Kettle Hill was taken, though casualties were heavy. The rest of San Juan Heights was taken within the hour following. The Rough Riders’ charge on Kettle Hill was facilitated by a hail of covering fire from three Gatling Guns commanded by Lt. John H. Parker, which fired some 18,000 .30 Army rounds into the Spanish trenches atop the crest of both hills. Col. Roosevelt noted that the hammering sound of the Gatling guns visibly raised the spirits of his men: “There suddenly smote on our ears a peculiar drumming sound. One or two of the men cried out, “The Spanish machine guns!” but, after listening a moment, I leaped to my feet and called, “It’s the Gatlings, men! Our Gatlings” Immediately the troopers began to cheer lustily, for the sound was most inspiring.” Trooper Jesse D. Langdon of the 1st Volunteer Infantry, who accompanied Col. Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders in their assault on Kettle Hill, reported: “We were exposed to the Spanish fire, but there was very little because just before we started, why, the Gatling guns opened up at the bottom of the hill, and everybody yelled, “The Gatlings! The Gatlings!” and away we went. The Gatlings just enfiladed the top of those trenches. We’d never have been able to take Kettle Hill if it hadn’t been for Parker’s Gatling guns.” A Spanish counterattack on Kettle Hill by some 600 infantry was quickly decimated by one of Lt. Parker’s Gatling guns recently emplaced on the summit of San Juan Hill, which killed all but forty of the attackers before they had closed to within 250 yards of the Americans on Kettle Hill. Col. Roosevelt was so impressed by the actions of Lt. Parker and his men that he placed his regiment’s two 7mm Colt-Browning machine guns and the volunteers manning them under Parker, who immediately emplaced them – along with 10,000 rounds of captured 7mm Mauser ammunition – at tactical firing points in the American line. Colonel Roosevelt’s example of valor and fearlessness in the face of danger served as motivation to his men to promptly follow his command and spring into the fray. Had it been another leader with less charisma and spunk, the order to charge may not have been given and the cavalry may not have had the same enthusiasm in their charge uphill. As for Roosevelt himself, he gave most of the credit to Lt. Parker and his Gatling Gun Detachment: “I think Parker deserved rather more credit than any other one man in the entire campaign… he had the rare good judgment and foresight to see the possibilities of the machine-guns. He then, by his own exertions, got it to the front and proved that it could do invaluable work on the field of battle, as much in attack as in defense.” Colonel Roosevelt and the Rough Riders played a key role in the outcome of the Spanish-American war by serving as the catalyst with other American units on constricting the ring around the city of Santiago. The ultimate goal of capturing the San Juan Heights (also known as Kettle Hill and San Juan Hill) was from that strategic position to move downhill and take Santiago de Cuba, a strong point for the Spanish army. The Spanish had a fleet of their cruisers in port. By taking areas around Santiago and consequently moving in on the city from many sides, the United States hoped to scare the Spanish cruisers into leaving port out to sea where they would encounter the United States Navy. This, in fact, was the exact result. Only a couple of days after the battle on San Juan Heights, the Spanish cruiser fleet was quickly sunk. This took a tremendous toll on the Spanish army due to the fact that a large portion of a nation’s military power lies upon their naval capabilities. However, the sinking of the Spanish cruisers did not mean the end of the war. Battles continued in and around Santiago. By July 17 the Spanish forces in Santiago surrendered to General Shafter and the United States military. Various battles in the region continued on and the United States was continuously victorious. On August 12 the Spanish Government surrendered to the United States and agreed to an armistice that relinquished their control of Cuba. The armistice also gained the United States the territories of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. This was an enormous turning point for America which had been wounded by civil war for over thirty years. Gaining such a large mass of land all at once brought the United States up on the ladder of world powers. The Spanish-American War also began a trend of United States intervention in foreign affairs which has lasted to present day. On August 14 the Rough Riders landed at Montauk Point in Long Island, New York. There, they met up with the other four companies that had been unfortunately left behind in Tampa. Colonel Roosevelt made note of how very many of the men who were left behind felt guilty for not serving in Cuba with the others. However, he also stated that “those who stayed had done their duty precisely as did those who went, for the question of glory was not to be considered in comparison to the faithful performance of whatever was ordered.” During the first portion of the month that the men stayed in Montauk they received hospital care. Many of the men were stricken with Malarial fever (described at the time as “Cuban fever”) and died in Cuba, while some were brought back to the United States on board the ship in makeshift quarantine. “One of the distressing features of the Malaria which had been ravaging the troops was that it was recurrent and persistent. Some of the men died after reaching home, and many were very sick.” Aside from malaria, there were cases of yellow fever, dysentery and other illnesses. Many of the men suffered from general exhaustion and were in poor condition upon returning home, some twenty pounds lighter. Everyone received fresh food and most were nourished back to their normal health. The rest of the month in Montauk, New York was spent in celebration of victory among the troops. The regiment was presented with three different mascots that represented the Rough Riders: a mountain lion by the name of Josephine that was brought to Tampa by some troops from Arizona, a war eagle named in Colonel Roosevelt’s honor brought in by some New Mexican troops, and lastly a small dog by the name of Cuba who had been brought along on the journey overseas. Accompanying the presented mascots was a young boy who had stowed away on the ship before it embarked to Cuba. He was discovered with a rifle and boxes of ammunition and was, of course, sent ashore before departure from the United States. He was taken in by the regiment that was left behind, given a small Rough Riders uniform, and made an honorary member. The men also made sure to honor their colonel in return for his stellar leadership and service. They presented him with a small bronze statue of Remington’s “The Bronco-buster” which portrayed a cowboy riding a violently bucking horse. “There could have been no more appropriate gift from such a regiment … most of them looked upon the bronze with the critical eyes of professionals. I doubt if there was any regiment in the world which contained so large a number of men able to ride the wildest and most dangerous horses.” After the turning over of their gift, each and every man in the regiment walked by and shook Colonel Roosevelt’s hand and bid him a good-bye. On the morning of September 15 the regimental property including all equipment, firearms and horses were turned back over to the United States government. The soldiers said one last good-bye to each other and the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, was disbanded at last. Before they all returned to their respective homes across the country, Colonel Roosevelt gave them a short speech that commended their efforts in the war, expressed his profound pride and reminded them that, although heroes, they would have to integrate back into normal society and work as hard as everyone else. Many of the men were unable to gain their jobs back from when they lost them before leaving for war. Some, due to illness or injury, were unable to work for a long time. Money was donated by a number of wealthier supporters of the regiment and used to supplement the wellbeing of the needy veterans, many of whom were too proud to accept the help. A first reunion of the Rough Riders was held in the Plaza Hotel in Las Vegas, New Mexico in 1899. Roosevelt, then Governor of New York, attended this event. In 1948, fifty years after the Rough Riders disbandment, the U.S. Post office issued a commemorative stamp in their honor and memory. The stamp depicts Captain William Owen “Bucky” O’Neill, who was killed in action while leading A Troop at the Battle of San Juan Hill, July 1, 1898. The Rough Riders continued to have annual reunions in Las Vegas until 1967, when the sole veteran to attend was Jess Langdon. He died in 1975.

The last two surviving veterans of the regiment were Frank C. Brito and Jesse Langdon. Brito, from Las Cruces, New Mexico, whose father was a Yaqui Indian stagecoach operator, was 21 when he enlisted with his brother in May 1898. He never made it to Cuba, having been a member of H Troop, one of the four left behind in Tampa. He later became a mining engineer and lawman. He died April 22, 1973, at the age of 96. Langdon, born 1881 in what is now North Dakota, “hoboed” his way to Washington, D.C., and called on Roosevelt at the Navy Department, reminding him that his father, a veterinarian, had treated Roosevelt’s cattle at his Dakota ranch during his ranching days. Roosevelt arranged a railroad ticket for him to San Antonio, where Langdon enlisted in the Rough Riders at age 16. He was the last surviving member of the regiment and the only one to attend the final two reunions, in 1967 and 1968. He died June 29, 1975 at the age of 94, twenty-six months after Brito. |

The names of the Rough Riders from New Mexico, as obtained from the muster-out roll, are as follows:

| Field and Staff |

| Major, Henry B. Hersey, Santa Fe First Lieutenant and Quartermaster, Sherrard Coleman. Santa Fe First Lieutenant and Adjutant, Thomas W. Hall, Lake Valley, on account of disability tendered his resignation, which took effect August 1, 1898. |

| Hospital Corps |

| First Lieutenant. James A. Massie, Santa Fe Steward, James B. Brady, Santa Fe Steward, Herbert J. Rankin, Las Vegas |

Troop A

| Corporal, George L. Bugbee, Lordsburg | |

| Troopers | |

| Fred W. Bugbee, Lordsburg* William Bulzing, Santa Fe |

Lawrence E. Huffman. Las Cruces Harry B. Pierce, Central City |

| *Wounded in head in battle of San Juan, July 1, 1898 | |

Troop B

| Troopers | |

| James A. Butler, Albuquerque Robert Day, Santa Fe John C. Peck, Santa Fe |

George C. Whittaker, Silver City Wallace W. Wilkerson, Santa Fe |

Troop D

| Troopers | |

| Charles H. Green, Albuquerque Emmett Laird, Albuquerque |

Eugene Schupp, Santa Fe Theodore Folk*, Oklahoma City, N. M. |

| *Transferred to Troop K. U. S. V. C, May 11, 1858. | |

Troop C

| Field and Staff | |

| Captain, William H. H. Llewellyn, Las Cruces First-lieutenant, John Wesley Green, Gallup Second-lieutenant, David J. Leahy, Raton* First-sergeant, Columbus H. McCaa, Gallup Q.-M. Sergeant, Jacob S. Mohler, Gallup Sergeant, Rolla A. Fullenweiden, Raton Sergeant, Matthew T. McGehee. Raton Sergeant, James Brown, Gallup Corporal, Henry Kirah, Gallup Corporal, James D. Ritchie, Gallup Corporal, Luther L. Stewart, Raton** |

Corporal, John McSparron, Gallup+, 1 Corporal, Frank Briggs, Raton Corporal, Edward C. Armstrong, Albuquerque Corporal, William S. Reid, Raton Corporal, Hiram E. Williams, Raton Farrier, George V. Haefner, Gallup Saddler, Frank A. Hill, Raton Wagoner, Thomas O’Neal, Springer Trumpeter, Willis E. Somers, Raton Trumpeter, Edward G. Piper, Silver City |

| *On sick list from July I to Sept. 3, from wound received in San Juan battle **Wounded in battle June 24 +Wounded July |

|

Troopers

| Alvin C. Ash*, Raton, Arthur T. Anderson, Albuquerque Robert Brown, Gallup John J. Beissel, Gallup Cloid Camp, Raton Marion Camp, Raton Thomas F. Cavenaugh,**Raton Michael H. Coyle,** Raton Frederick Fornoff, Albuquerque Wm. C. Gibson, Gallup John Goodwin, Gallup John Henderson, Gallup* Albert John Johnson, Raton John S. Kline, San Marcial Bert T. Keeley, Lamy Elias M. Littleton, Springer Fred, P. Meyers+ Gallup Daniel Moran, Gallup John Noish, Raton T. W. Phipps, Bland |

Archibald Petty, Gallup George H. Quigg, Gallup Walter D. Quinn, San Marcial Wm. Radcliff. Gallup Richard Richards, Albuquerque Robert W. Reid**, George Roland, Deming** Charles M. Simmons, Raton Charles W. Shannon, Raton Neal Thomas, Aztec Grant Travis, Aztec Richard Whittington, Gallup Lyman E. Whited, Raton William D. Wood, Bland Clarence Wright, Springer George D. Swan++, Gallup Frank M. Thompson++, Aztec Samuel T. McCulloch#, Springer Eugene A. Lutz, Raton## Henry J. Haefner*** Gallup |

| *Absent from July I to Sept. 7 on account of wound received in battle; **Raton, wounded June 24 *** Killed in battle June 24. +reduced from 1st Sergeant, to trooper on account of absence caused by wound received in battle July 1 ++Discharged on account of disability #Deserted from camp at Tampa, Florida, August 4, 1898. ##Died in yellow fever hospital. August 15, 1898. |

|

| Transferred to Troop I May 12, 1898 | |

| Sergeant Henry J. Arendt, Gallup | |

| Henry C. Bailie, Gallup Wm. J. Love, Raton Evan Evans. Gallup Oscar W. Groves, Raton Wm. H. Jones, Raton |

John H. Tait. Raton Harry Peabody, Raton Alexander McGowan, Gallup John Brown, Gallup Joseph B. Crockett, Raton |

Troop E

| Field and Staff | |

| Captain, Frederick Muller, Santa Fe First-lieutenant, Wm. E. Griffin, Santa Fe First-sergeant, John S. Langston, Cerrillos Quartermaster-sergeant, Royal A. Prentice, Las Vegas Sergeant, Hugh B. Wright, Las Vegas Sergeant, Albert M. Jones, Santa Fe Sergeant, Timothy Breen, Santa Fe* Sergeant, Berry F. Taylor, Las Vegas Sergeant, Thomas P. Ledgwidge, Santa Fe Corporal, Harmon H. Winkoop, Santa Fe,** |

Corporal, James M. Dean, Santa Fe,*** Corporal, Richard C. Conner, Santa Fe Corporal, Ralph E. McFie, Las Cruces Trumpeter, Arthur J. Griffin, Santa Fe Trumpeter, Edward S. Lewis, Las Vegas Blacksmith, Robert J. Parrish, Clayton Farrier, Grant Hill, Santa Fe Saddler, Joe T. Sandoval. Santa Fe Wagoner, Guilford B. Chapin, Santa Fe |

| *wounded in arm and sent to hospital July 1, 1898; **wounded in line of duty and sent to hospital July 2, 1898; returned to duty Sept. 4, 1898 ***wounded in left thigh, in line of duty, and sent to hospital June 24, 1898; returned to duty August 31, 1898 |

|

Troopers

| Roll Almack, Santa Fe John M. Brennan, Santa Fe Jose M. Baca, Las Vegas George W. Dettamore, Clayton* Freeman M. Donavan, Santa Fe Wm. T. Easley, Clayton Frank D. Fries, Santa Fe Joseph Gisler, Santa Fe James P. Gibbs, Santa Fe Wm. R. Gibbie, Las Vegas John D. Harding, Socorro Daniel D. Harkness, Las Vegas Wm. M. Hutchison, Santa Fe Wm. H. Hogle, Santa Fe Arthur J. Hudson, Santa Fe John Hulskotter, Santa Fe Wm. S. E. Howell, Cerrillos Thomas L. Hixon, Las Vegas Thomas B. Jones, Santa Fe Charles W. Jacobus, Santa Fe Charles E. Kingsley, Las Vegas Frank Lowe, Santa Fe Dan Ludy, Las Vegas Hyman S. Lowitzki, Santa Fe |

James E. Merchant, Cerrillos Wm. J. Moran, Cerrillos Samuel McKinnon, Madrid Charles E. McKinley, Cerrillos** Charles F. McKay, Santa Fe Frederick A. McCabe, Santa Fe John C. McDowell. Santa Fe Amaziah B. Morrison, Las Vegas Lloyd L. Mahan, Cerrillos Henry D. Martin. Cerrillos Otto F. Menger, Clayton*** Wm. C. Mungor, Santa Fe Adolph F. Nettleblade, Cerrillos Thomas Roberts, Golden John E. Ryan, Santa Fe,**** Ben F. Seaders, Las Vegas Arthur V. Skinner, Santa Fe Wm. C. Schnepple, Santa Fe Edward Scanlon, Cerrillos Wm. W. Wagner, Bland George Wright, Madrid Charles W. Wynkoop, Santa Fe George W. Warren, Santa Fe |

| *Wounded in line of duty and sent to hospital July 1, 1898 **Wounded in head in line of duty July I, 1898 ***Wounded in left side July I, 1898 ****Wounded July I, 1898 |

|

First Sergeant William E. Dame, Cerrillos, discharged per O. reg. commands, August 10, 1898

Sergeant, Frederick C. Wesley, Santa Fe, wounded July 1, 2 or 3, 1898, and discharged on account of disability August 26, 1898.

Troop F

| Field and Staff | |

| Captain, Maximilian Luna First-lieutenant, Horace W. Weakley Second-lieutenant, William E. Dame* First Sergeant, Horace E. Sherman Sergeant, Garfield Hughes Sergeant, Thomas D. Tennessy Sergeant, Wm. L. Mattocks Sergeant, James Doyle Sergeant, George W. Armijo** Sergeant, Eugene Bohlinger Sergeant, Herbert A. King |

Corporal, Edward Donnelly Corporal, John Cullen Corporal, Edward Hale Corporal, Arthur P. Spencer Corporal, John Boehnke Corporal, Albert Powers+ Corporal, Wentworth S. Conduit Farrier, Ray V. Clark++ Farrier, Charles R. Gee Wagoner, Jefferson Hill Bugler, Arthur L. Perry# |

| *Transferred from Troop E to F **Wounded in action June 24, 1898 +Wounded in action July 1, 1898 ++Wounded July 1, 2 or 3, 1898 #Wounded July 1, 2 or 3; all from Santa Fe |

|

Troopers***

| H. L. Albers* Ed. J. Albertson* James Alexander Chas. G. Abbott James F. Alexander Tames S. Black Robert Z. Bailey* Jeremiah Brennan Walter C. Burris John H. Bell Wm. O. Cochran Calvin G. Clelland Edward C. Conley Willard M. Cochran Charles C. Cherry Louis Dougherty |

John C. De Bohun Wm. Farley Will Freeman** Henry M. Gibbs** Wm. D. Gallagher Samuel Goldberg** Otis Glessner John D. Green Albert C. Hartle* Charles O. Hopping George Hammer Stephan A. Kennedy Charles E. Leffert Guy M. Lisk John M. Leach Thomas Martin |

John B. Mills Herbert P. McGregor** William E. Nickell Otto W. Nesbit George W. Newitt John M. Neal Charles A. Parmele Frank T. Quier Millard L. Raymond Harry B. Reed Clifford L. Reed* Charles L. Renner Edwin L. Reynolds Arthur L. Russell Adolph T. Reyer Albert Rogers |

Lee C. Rice Louis E. Staub Wm. G. Shields Arthur H. Stockbridge George H. Sharland John G. Skipwith James B. Sinnett Edward Tangen Norman O. Trump George E. Vinnedge Louis C. Wardwell Paul Warren Charles E. Watrous Beauregard Weber John Walsh Thomas J. Wells |

||

| *Wounded in action June 24, 1898 **Wounded July 1, 1898 ***All from Santa Fe |

|||||

| Private James Douglass. Santa Fe, discharged on account of disability. Second-lieutenant Maxwell Keyes, Santa Fe, promoted to Adjutant August 1, 1898 |

|||||

| Privates transferred from Troop F to I, May 12, 1808 | |||||

|

|||||

Troop H

| Captain, George Curry, Tularosa First-lieutenant, William H. Kelly, Las Vegas Second-lieutenant. Charles L. Ballard, Roswell Sergeant, Nevin P. Gutilius, Tularosa Sergeant, Oscar de Montell, Roswell Sergeant, Michael C. Rose, Silver City Sergeant, Nova A. Johnson, Roswell Corporal, Marton M. Morgan, Silver City |

Corporal, Arthur E. Williams, Las Cruces Corporal, Frank Murray, Roswell Corporal, Morgan O. B. Llewellyn, Las Cruces Corporal, James C. Hamilton, Roswell Corporal, Charles P. Cochran, Eddy Trumpeter, Gaston R. Dehumy, Santa Fe Farrier, Robert L. Martin, Santa Fe Wagoner, Taylor B. Lewis, Las Cruces |

Troopers

| Albert B. Amonette, Roswell Columbus L. Black, Las Cruces John B. Bryan, Las Cruces Frank Bogardus, Las Cruces Thomas F. Corbett, Roswell John S. Cone, Tularosa Abell B. Duran, Silver City Jose L. Duran, Santa Fe Lewis Dorsey, Silver City George B. Doty, Santa Fe Frederick W. Dunkle, Las Vegas Arthur L. Douglas, Eddy Frank A. Eaton, Silver City Augustus C’ Fletcher, Silver City James B. Grisby, Deming James M. Hamilton, Deming |

Leary O. Herring, Silver City Robert C. Houston, Hillsboro Amandus Kehn, Silver City Frank H. Lawson, Las Cruces John Lannon, Hillsboro Thomas A. Mooney, Silver City George F. Murray, Deming Charles H. Ott, Silver City Lory H. Powell, Roswell Norman W. Pronger, Silver City John F. Pollock, Tularosa Alexander M. Thompson, Deming Daniel G. Waggoner, Roswell Curtis C. Waggoner, Roswell Patrick A. Wickham, Socorro |

| Transfers Sergeant John V. Morrison, Santa Fe |

|

| Robert E. Lee. Donahue C. Darwin Casad, Las Cruces Numa C. Fringer. Las Cruces |

George Schafer. Pinos Altos Morris J. Storms. Roswell |

| Edwin Eugene Casey. Las Cruces, died in hospital at Camp Wyckoff. New York. September 1, 1898. Samuel Miller, Roswell, deserted from Tampa. Florida, June 28. 1898. |

|

Troop I

| Field and Staff | |

| First-lieutenant. Frederick W. Wintge, Santa Fe First-sergeant. John B. Wylie, Fort Bayard Sergeant, William H. Waffensmith, Raton Corporal, Numa C. Frenger, Las Cruces |

Corporal, William J. Sullivan, Silver City Corporal, William J. Nehmer, Silver City Corporal, Hiram T. Brown, Albuquerque Trumpeter, Robert E. Lea, Dona Ana |

Troopers

| Horton A. Bennett, Tularosa Frank C. Brito, Pinos Altos Jose Brito*, Santa Fe Charles D. Casad, Mesilla George M. Coe. Albuquerque Henry C. Davis, Santa Fe Thomas P. Dolan, Pinos Altos Robert W. Denny, Raton Evan Evans, Gallup Joseph F. Flynn, Albuquerque John R. Gooch, Santa Fe Oscar W. Groves, Raton Hedrick Ben Goodrich, Santa Fe Ernest H. Hermeyer, Roswell William H. Jones, Raton |

Cal Jopling, La Luz Harry B. King, Raton Alexander McGowan, Gallup Ben F. T. Morris, Raton Roscoe E. Moore, Raton Harry Peabody, Raton John P. Roberts, Clayton Louis Larsen. Santa Fe Carl J. Scheamhorst, Jr., Santa Fe George Schafer, Pinos Altos John H. Tait, Santa Fe John L. Twyman, Raton Harry B. Wiley, Santa Fe Roy O. Wisenberg, Raton |

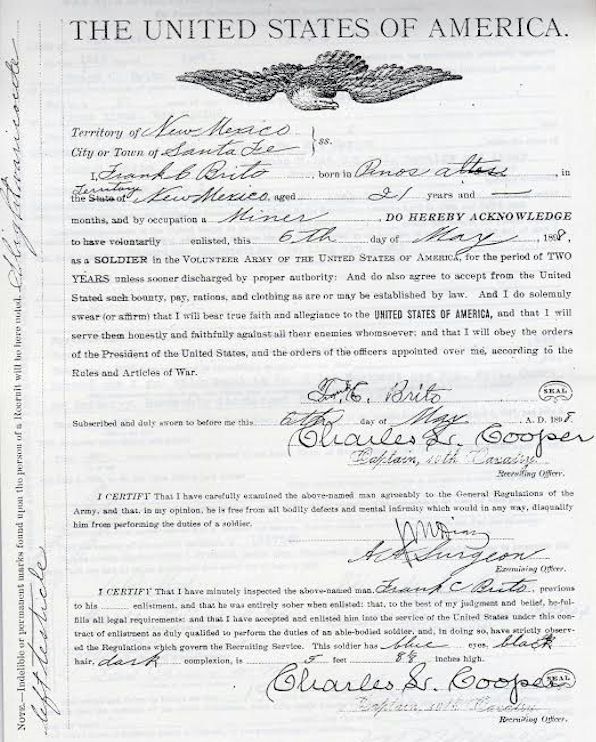

| * Added with Enlistment Papers as proof. | |

Troop K

First-sergeant, Frederick K. Lee, Organ

Troopers

| William C. Bernard, Las Vegas | Stephen Easton*, Santa Fe | Joseph L. Duran, Santa Fe |

| *Transferred to Troop H, July 15, 1898 | ||

source: History of New Mexico

Frank Brito of the Rough Riders

1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, Troop I

(1877 – 1973) By Frank Brito (Grandson)

One April 1898 morning found Frank C. Brito out tending cattle with his older brother Jose for the Circle Bar Ranch near Silver City, New Mexico. He was making $1 a day working as a 20-year-old cowboy. He and Jose received a message from their father to return home immediately to Pinos Altos, a small mining town at the edge of the Gila Wilderness in southwestern New Mexico. Their father was Santiago Brito, a Yaqui Indian mine owner and stage coach operator originally from Janos, Mexico.

Frank was born on August 24, 1877 in Pinos Altos, still a killing ground between citizens and the bands of Apaches under Geronimo, Victorio, Juh and Nana. He studied at the local grammar school and became a printer’s apprentice, then a miner. The average employee made no more than $30 a month and worked long hours, usually at hard labor in the mines, ore mills or outdoors.

After a long ride home and listening to their father, Frank and Jose did as they were told and were enlisted as volunteer privates at Santa Fé, New Mexico on May 6, 1898. Frank was three months short of age 21 and his occupation listed as “miner.” Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt and Col. Leonard Wood, as commander, formed the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, also known as the “Rough Riders,” to fight in the Spanish-American War. They chose cowboys, miners and college athletes as their soldiers of choice. The Brito brothers were assigned to Troop H captained by George Curry, a future New Mexico territorial governor. Curry and Frank Brito were to remain lifelong friends. Shortly thereafter they were transferred to Troop I captained by Schuyler McGinnis. Here, Frank had as his bunkmate, Numa Frenger, later a District Judge in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

They were shipped to San Antonio, Texas where the men were drilled in cavalry basics until the end of May. On the 29th, they were shipped to Tampa, Florida. Because he was bilingual in speaking, reading, and writing in Spanish, Frank was placed in charge of the stockade established to deal with the potential Spanish prisoners of war. To his pleasure, he met Theodore Roosevelt and was nicknamed “Monte” by him, short for “Montezuma.”

The men had some time for enjoyment during the seemingly endless preparations for war. Frank Brito, described an event that occurred in a shooting gallery in Ybor City, Florida while the men were seeking some sort of entertainment to break up the monotony of camp life. The shooting gallery was quite popular among the many troops stationed nearby. Frank Brito stated:

“I went in one time with Tom Darnell [a Sergeant in H Troop from Denver, Colorado who was later killed, according to Mr. Brito, while trying to shoot up the town of Central City, near Santa Rita, New Mexico] and some other troopers and we paid 25 cents to get in. There were bales of cotton behind the moving targets to catch the .22 caliber bullets and the whole place was surrounded with a fence of chicken wire. We told the man we would use our own six-shooters instead of the .22’s and when we all started shooting, it scared hell out of everybody and people started jumping over that chicken wire fence. Somebody called the 10th Georgia Cavalry to quiet us down but we took the pins off our hats and nobody knew for a while that we were Rough Riders. The Colonel found out but by then it had all blown over. “

The revolvers used by the Rough Riders were Colt single action artillery models with a 5 ½” barrel and shot the powerful .45 Colt cartridge. The noise would have been deafening!

Unfortunately, Frank never made it to Cuba, remaining in Tampa with the stockade, most of the horses, the men of his troop and three other troops. The reason that Frank did not go to Cuba was that, because of a shortage of space aboard the transport ships, only eight of the regiment’s twelve troops were permitted to board for Cuba. Also, because of the space shortage, those that did go to Cuba went without their horses, which were left behind for Frank’s I Troop, joined by C, H, and M Troops, to care for.

The orders splitting the regiment met with protest. Roosevelt noted that “the four [Troops] left behind feel fearfully.” Later he added “To the great bulk of them I think it will be a life-long sorrow. I saw more than one, both among the officers and privates, burst into tears…”

Partially to assuage them, those remaining behind were told by Colonel Wood that they would shortly be taken to Cuba also. Brito commented “We were too angry to hear him, and if we had, I doubt we would have believed him. We had come a long way together and being left out at the last minute was not something any of us had counted on.”

At the war’s end, all the Rough Riders were reunited at Camp Wikoff, Montauk Point on Long Island, New York to recover from their wounds and tropical diseases. Frank spent time in a New Jersey hospital recovering from malaria and dysentery prevalent in the Tampa area.

Frank was discharged from the Rough Riders on September 15, 1898. His brother remained in the service, joining another military unit after the Rough Riders were disbanded and was listed as “missing” in the Philippines during the latter phase of the Philippine-American War. Jose never returned and was presumed dead.

Frank returned to mining in Pinos Altos and was involved in a tragedy in September 1900. He returned home during the day and mistakenly killed his wife’s sister. He was sentenced to the territorial prison for ten years but served only five. Territorial Governor Miguel Otero granted him a full pardon. In prison, he learned the emerging technology of electricity in operating dynamos and motors. During this time, he was divorced from his first wife.

He worked as a hoisting engineer at various mines, which required a high degree of skill, lowering equipment and men into deep shafts. Leaving Silver City, he moved to Las Cruces and was married a second time. He was also an electrician for the city of Las Cruces after his mining days were over. He later became a deputy sheriff, town constable, city jailor and game warden. Frank C. Brito was praised for a long and useful law enforcement career.

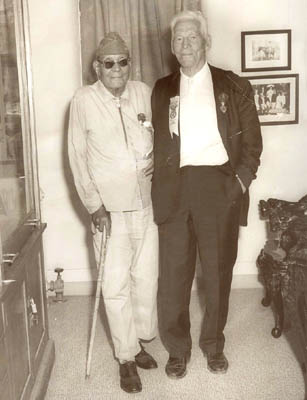

Las Cruces Town Constable Frank Brito, right, with his deputy, Santa Rosa Rico, left. The photo is from about 1917.

In his first days in Las Cruces, Frank held a part-time job as bartender at various saloons. He worked for John Barncastle’s saloon and Dan Read’s Cowboy Saloon. At the Cowboy Saloon, he met and became friends with Pat Garrett, the law officer who tracked and killed Billy-the Kid. Frank’s seven children went to school with several of Garrett’s children.

There were numerous reunions of the Rough Riders, the first taking place at Prescott, Arizona. There is a statue of Bucky O’Neill in the city park with a plaque listing all the Rough Riders. Frank’s name is not on this plaque, however, his brother’s name is on the plaque. It was probably thought Frank and Jose Brito were the same person. Both brothers’ names are listed on all the original regiment records so there is an opportunity for the City of Prescott to correct this oversight. The later reunions were held at Las Vegas, New Mexico. The Rough Rider Museum was established in Las Vegas to commemorate this patriotic group. Las Vegas is not far from Santa Fé and this museum is worth visiting as it houses many artifacts dealing with this period.

Frank retired and spent his later life enjoying his family, friends, televised baseball, and stray cats. He enjoyed talking about his Spanish American War year and was interviewed many times by magazines, newspapers and historians. He was appointed as a Colonel and Aide-de-Camp to New Mexico Governor David F. Cargo on July 8, 1968 for his longevity as the sole remaining New Mexico Rough Rider and for many years of public service.

Frank C. Brito died on April 22, 1973, the penultimate Rough Rider to endure. He was 96 years old.

Bibliography: Brito Family – Information from Santiago and Frank Brito.

Jones, Virgil Carrington, Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. (New York: Doubleday, 1971) 57-58, 287.

Walker, Dale L., “The Last Rough Riders,” Rough Writings: Perspectives on Buckey O’Neill, Pauline O’Neill and Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. (Prescott, AZ: Sharlot Hall Museum Press, 1998) 13

Walker, Dale L., “The Next to the Last Man: Rough Rider Frank Brito,” Nova (a publication of the University of Texas at El Paso). February – April 1971 edition, vol.6, no.2.

http://www.donaanacountyhistsoc.org/HistoricalReview/2019/Review%202019%20WEB%20VER.pdf

The Rough Riders was a nickname given to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, one of three such regiments raised in 1898 for the Spanish–American War and the only one of the three to see action. The United States Army was small and understaffed in comparison to its status during the American Civil War roughly thirty years prior. As a measure towards rectifying this situation President William McKinley called upon 1,250 volunteers to assist in the war efforts. The regiment was also called “Wood’s Weary Walkers” in honor of its first commander, Colonel Leonard Wood. This nickname served to acknowledge that despite being a cavalry unit they ended up fighting on foot as infantry.

Wood’s second in command was former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, a man who had pushed for American involvement in the Cuban War of Independence. When Colonel Wood became commander of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, the Rough Riders then became “Roosevelt’s Rough Riders.” That term was familiar in 1898, from Buffalo Bill who called his famous western show “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World.” The Rough Riders were mostly made of college athletes, cowboys, ranchers, miners, and other outdoorsmen. A common trait shared by many members of the regiment was a shared origin. With these men being from southwestern ranch country, they were quite skilled in horsemanship.

The rough riders by Theodore Roosevelt full audiobook

Formation and early history

The volunteers were gathered in four areas: Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas. They were gathered mainly from the southwest because the hot climate region that the men were used to was similar to that of Cuba where they would be fighting. “The difficulty in organizing was not in selecting, but in rejecting men.” The allowed limit set for the volunteer cavalry men was promptly met. They gathered a diverse bunch of men consisting of cowboys, gold or mining prospectors, hunters, gamblers, Native Americans and college boys — all of whom were able-bodied and capable on horseback and in shooting. Among these men were also police officers and military veterans who wished to see action again, most of which had previously retired. Men who had served in the regular army during campaigns against Native Americans or served in the Civil War had been gathered to serve as higher ranking officers in the cavalry. In this regard they possessed the knowledge and experience to lead and train the men well. As a whole, the unit would not be entirely inexperienced. Leonard Wood, a doctor who served as the medical adviser for both the President and Secretary of War, was appointed the position of Colonel of The Rough Riders with Roosevelt serving as Lieutenant-Colonel. One particularly famous spot where volunteers were gathered was in San Antonio, Texas, at the Menger Hotel Bar. The bar is still open and serves as a tribute to the Rough Riders, containing much of their, and Theodore Roosevelt‘s, uniforms and memorabilia.

Equipment

Before training began, Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt used his political influence gained as Assistant Secretary of the Navy to ensure that his volunteer cavalry regiment would be properly equipped to serve as any regular unit of the U.S. Army. For private soldiers and non-commissioned officers, this meant the M1892/98 Springfield (Krag) bolt-action rifle in .30 Army (.30-40) caliber: “They succeeded in getting their cartridges, revolvers (Colt .45), clothing, shelter-tents, and horse gear … and in getting the regiment armed with the Krag–Jørgensen carbine used by the regular cavalry.” Officers of the regiment each received a new lever-action M1895 Winchester rifle, also in .30 Army. The Rough Riders also used Bowie Hunter knives. A last-minute gift from a wealthy donor were a pair of modern tripod mounted, gas-operated M1895 Colt–Browning machine guns in 7mm Mauser caliber.

In contrast, the uniforms of the regiment were designed to set the unit apart: “The Rough Rider uniform was a slouch hat, blue flannel shirt, brown trousers, leggings, and boots, with handkerchiefs knotted loosely around their necks. They looked exactly as a body of cowboy cavalry should look.” This “rough and tumble” appearance contributed to earning them the title of “The Rough Riders.”

Training

Training was very standard, even for a cavalry unit. They worked on basic military drills, protocol, and habits involving conduct, obedience and etiquette. The men proved eager to learn what was necessary, and the training went smoothly. It was decided that the men would not be trained to use the saber as other cavalries often used, because they had no prior experience with that combat skill. Instead, they chose to have the men stick to the use of their carbines and revolvers as primary and secondary weapons. Although the men, for the most part, were already experienced horsemen, the officers refined their techniques in riding, shooting from horseback, and practicing in formations and in skirmishes. Along with these practices, the high-ranking men heavily studied books filled with tactics and drills to better themselves in leading the others. During times which physical drills could not be run, either because of confinement on board the train, ship, or during times where space was inadequate, there were some books that were read further as to leave no time wasted in preparation for war. The competent training that the volunteer men received prepared them best as possible for their duty. They were not simply handed weapons and given vague directions to engage in a disorderly brawl.

On May 29, 1898, 1060 Rough Riders and 1258 of their horses and mules made their way to the Southern Pacific railroad to travel to Tampa, Florida where they would set off for Cuba. The lot awaited orders for departure from Major General William Rufus Shafter. Under heavy prompting from Washington D.C., General Shafter gave the order to dispatch the troops early before sufficient traveling storage was available. Due to this problem, only eight of the twelve companies of The Rough Riders were permitted to leave Tampa to engage in the war, and many of the horses and mules were left behind. Aside from Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt’s first hand mention of deep, heartfelt sorrow from the men left behind, this situation resulted in a premature weakening of the men. Approximately one fourth of them who received training had already been lost, most dying of malaria and yellow fever. This sent the remaining troops into Cuba with a significant loss in men and morale.

Upon arrival on Cuban shores on June 23, 1898, the men promptly unloaded themselves and the small amount of equipment they carried with them. Camp was set up nearby and the men were to remain there until further orders had been given to advance. Further supplies were unloaded from the ships over the next day including the very few horses that were allowed on the journey. “The great shortcoming throughout the campaign was the utterly inadequate transportation. If they had been allowed to take our mule-train, they could have kept the whole cavalry division supplied.” Each man was only able to carry a few days worth of food which had to last them longer and fuel their bodies for rigorous tasks. Even after only seventy-five percent of the total number of cavalry men was allowed to embark into Cuba they were still without most of the horses they had so heavily been trained and accustomed to using. They were not trained as infantry and were not conditioned to doing heavy marching, especially long distance in hot, humid, and dense jungle conditions. This ultimately served as a severe disadvantage to the men who had yet to see combat.

Battle of Las Guasimas

Within another day of camp being established, men were sent forward into the jungle for reconnaissance purposes, and before too long they returned with news of a Spanish outpost, Las Guasimas. By afternoon, The Rough Riders were given the command to begin marching towards Las Guasimas, to eliminate opposition and secure the area which stood in the path of further military advance. Upon arrival at their relative destination, the men slept through the night in a crude encampment nearby the Spanish outpost they would attack early the next morning.

The Spanish held an advantage over the Americans by knowing their way through the complicated trails in the area of combat. They predicted where the Americans would be traveling on foot and exactly what positions to fire on. They also were able to utilize the land and cover in such a way that they were difficult to spot. Along with this, their guns used smokeless powder which did not give away their immediate position upon firing as other gunpowders would have. This increased the difficulty of finding the opposition for the U.S. soldiers. In some locations the jungle was too thick to see very far.

General Young, who was in command of the regulars and cavalry, began the attack in the early morning. Using long-range, large-caliber Hotchkiss guns he fired at the opposition, who were reportedly concealed along trenches, roads, ridges, and jungle cover. Colonel Wood’s men, accompanied by Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt, were not yet in the same vicinity as the other men at the start of the battle. They had a more difficult path to travel around the time the battle began, and at first they had to make their way up a very steep hill. “Many of the men, footsore and weary from their march of the preceding day, found the pace up this hill too hard, and either dropped their bundles or fell out of line, with the result that we went into action with less than five hundred men.” Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt became aware that there were countless opportunities for any man to fall out of formation and resign from battle without notice as the jungle was often too thick in places to see through. This was yet another event that left the group with fewer men than they had at the start.

Regardless, The Rough Riders pushed forward toward the outpost along with the regulars. Using careful observation, the officers were able to locate where the opposition was hidden in the brush and entrenchments and they were able to target their men properly to overcome them. Toward the end of the battle, Edward Marshall, a newspaper writer, was inspired by the men around him in the heat of battle to pick up a rifle and begin fighting alongside them. When he suffered a gunshot wound in the spine from one of the Spaniards another soldier mistook him as Colonel Wood from afar and ran back from the front line to report his death. Due to this misconception, Roosevelt temporarily took command as Colonel and gathered the troops together with his leadership charisma. The battle lasted an hour and a half from beginning to end with The Rough Riders suffering only 8 dead and 31 wounded, including Captain Allyn K. Capron, Jr. Roosevelt came across Colonel Wood in full health after the battle finished and stepped down from his position to Lieutenant-Colonel.

The United States had full control of this Spanish outpost on the road to Santiago by the end of the battle. General Shafter had the men hold position for six days while additional supplies were brought ashore. During this time The Rough Riders ate, slept, cared for the wounded, and buried the dead from both sides. During the six day encampment, some men died from fever. Among those stricken by illness was General Joseph Wheeler. Brigadier General Samuel Sumner assumed command of the cavalry and Wood took the second brigade as Brigadier General. This left Roosevelt as Colonel of The Rough Riders.

The order was given for the men to march the eight miles along the road to Santiago from the outpost they had been holding. Originally, Colonel Roosevelt had no specific orders for himself and his men. They were simply to march to San Juan Heights where over one thousand Spanish soldiers held the area and hold position. It was decided that Brigadier General Henry Lawton’s division would be the main fighters in the battle while taking El Caney, a Spanish stronghold, a few miles away. The cavalry was to simply serve as a distraction while artillery and battery struck the Spanish from afar. Lawton’s infantry would begin the battle and The Rough Riders were to march and meet with them mid-battle. In this way, The Rough Riders were not seen as a critical tool to the United States Army in this battle.