They’re watching us: How to detect Pegasus and other spyware on your iOS device?

The infamous Pegasus spyware created by Israeli firm NSO can turn any infected smartphone into a remote microphone or camera. Here’s how to stay safe and know if you’ve been hacked

How does Pegasus and other spyware work discreetly to access everything on your iOS device?

Introduction

In today’s digital age, mobile phones and devices have evolved from being exclusive to a few to becoming an absolute need for everyone, aiding us in both personal and professional pursuits. However, these devices, often considered personal, can compromise our privacy when accessed by nefarious cybercriminals.

Malicious mobile software has time and again been wielded as a sneaky weapon to compromise the sensitive information of targeted individuals. Cybercriminals build complex applications capable of operating on victims’ devices unbeknownst to them, concealing the threat and the intentions behind it. Despite the common belief among iOS users that their devices offer complete security, shielding them from such attacks, recent developments, such as the emergence of Pegasus spyware, have shattered this pretense.

The first iOS exploitation by Pegasus spyware was recorded in August 2016, facilitated through spear-phishing attempts—text messages or emails that trick a target into clicking on a malicious link.

What is Pegasus spyware?

Developed by the Israeli company NSO Group, Pegasus spyware is malicious software designed to gather sensitive information from devices and users illicitly. Initially licensed by governments for targeted cyber espionage purposes, it is a sophisticated tool for remotely placing spyware on targeted devices to pry into and reveal information. Its ‘zero-click’ capability makes it particularly dangerous as it can infiltrate devices without any action required from the user.

Pegasus can gather a wide range of sensitive information from infected devices, including messages, audio logs, GPS location, device information, and more. It can also remotely activate the device’s camera and microphone, essentially turning the device into a powerful tool for illegal surveillance.

Over time, NSO Group has become more creative in its methods of unwarranted intrusions into devices. The company, which was founded in 2010, claims itself to be a “leader” in mobile and cellular cyber warfare.

Pegasus is also capable of accessing data from both iOS and Android-powered devices. The fact that it can be deployed through convenient gateways such as SMS, WhatsApp, or iMessage makes it an effortless tool to trick users into installing the spyware without their knowledge. This poses a significant threat to the privacy and security of individuals and organizations targeted by such attacks.

How does Pegasus spyware work?

Pegasus is extremely efficient due to its strategic development to use zero-day vulnerabilities, code obfuscation, and encryption. NSO Group provides two methods for remotely installing spyware on a target’s device: a zero-click method and a one-click method. The one-click method includes sending the target a regular SMS text message containing a link to a malicious website. This website then exploits vulnerabilities in the target’s web browser, along with any additional exploits needed to implant the spyware.

Zero-click attacks do not require any action from device users to establish an unauthorized connection, as they exploit ‘zero-day’ vulnerabilities to gain entry into the system. Once the spyware is installed, Pegasus actively captures the intended data about the device. After installation, Pegasus needs to be constantly upgraded and managed to adapt to device settings and configurations. Additionally, it may be programmed to uninstall itself or self-destruct if exposed or if it no longer provides valuable information to the threat actor.

Now that we’ve studied what Pegasus is and the privacy concerns it raises for users, this blog will further focus on discussing precautionary and investigation measures. The suggested methodology can be leveraged to detect not just Pegasus spyware but also Operation Triangulation, Predator spyware, and more.

Let’s explore how to check iOS or iPadOS devices for signs of compromise when only an iTunes backup is available and obtaining a full file system dump isn’t a viable option.

In recent years, targeted attacks against iOS devices have made headlines regularly. Although the infections are not widespread and they hardly affect more than 100 devices per wave, such attacks still pose serious risks to Apple users. The risks have appeared as a result of iOS becoming an increasingly complex and open system, over the years, to enhance user experience. A good example of this is the flawed design of the iMessage application, which wasn’t protected through the operating system’s sandbox mechanisms.

Apple failed to patch this flaw with a security feature called BlastDoorin iOS 14, instead implementing a Lockdown Mode mechanism that, for now, cybercriminals have not been able to bypass. Learn more about Lockdown Mode here.

While BlastDoor provides a flexible solution through sandbox analysis, Lockdown Mode imposes limitations on iMessage functionality. Nonetheless, the vulnerabilities associated with ImageIO may prompt users to consider disabling iMessage permanently. Another major problem is that there are no mechanisms to examine an infected iOS device directly. Researchers have three options:

- Put the device in a safe and wait until an exploit is developed that can extract the full file system dump

- Analyze the device’s network traffic (with certain limitations as not all viruses can transmit data via Wi-Fi)

- Explore a backup copy of an iOS device, despite data extraction limitations

The backup copy must be taken only with encryption (password protection) as data sets in encrypted and unencrypted copies differ. Here, our analysts focus on the third approach, as it is a pragmatic way to safely examine potential infections without directly interacting with the compromised device. This approach allows researchers to analyze the device’s data in a controlled environment, avoiding any risk of further compromising the device and losing valuable evidence that forms the ground for crucial investigation and analysis.

To conduct research effectively, the users will need either a Mac or Linux device. Linux virtual machines can also be used, but it is recommended that users avoid using Windows Subsystem for Linux as it has issues with forwarding USB ports.

In the analysis performed by Group-IB experts, we use an open-source tool called Mobile Verification Toolkit (MVT), which is supported by a methodology report.

Let’s start with installing dependencies:

Next, install a set of tools for creating and working with iTunes backups:

Lastly, install MVT:

cd mvt

pip3 install

Now, let’s begin with the analysis. To create a backup, perform the following:

- Connect the iOS device and verify the pairing process by entering your passcode.

- Enter the following command:

Users will receive a substantial output with information about the connected device, such as the iOS version and model type:

ProductType: iPhone12.5

ProductVersion: 17.2.1

After that, users can set a password for the device backup:

Enter the password for the backup copy and confirm it by entering your phone’s passcode.

As mentioned, the above step is crucial to ensure the integrity of the data extracted from the device.

Create the encrypted copy:

This process may take a while depending on the amount of space available on your device. Users will also need to enter the passcode again.

Once the backup is complete (as indicated by the Backup Successful message), the users will need to decrypt it.

To do so, use MVT:

After being through with the process, users may have successfully decrypted the backup.

Now, let’s check for known indicators. Download the most recent IoCs (Indicators of Compromise):

We can also track IoCs relating to other spyware attacks from several sources, such as:

“Predator Spyware Indicators of Compromise”

“RCS Lab Spyware Indicators of Compromise”

“Stalkerware Indicators of Compromise”

“Surveillance Campaign linked to mercenary spyware company”

“Quadream KingSpawn Indicators of Compromise”

“Operation Triangulation Indicators of Compromise”

“WyrmSpy and DragonEgg Indicators of Compromise”

- Indicators from Amnesty International’s investigations

- Index and collection of MVT compatibile indicators of compromise

The next step is to launch the scanning:

The users will obtain the following set of JSON files for analysis.

If any infections are detected, the users will receive a *_detected.json file with detections.

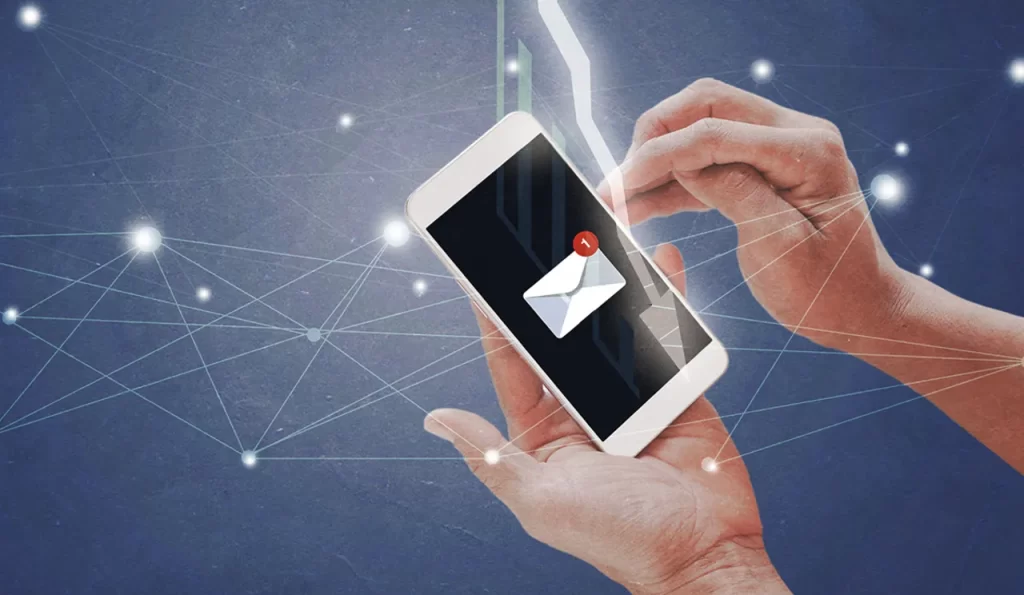

Image 1: Result of MVT IOCs scan with four detections

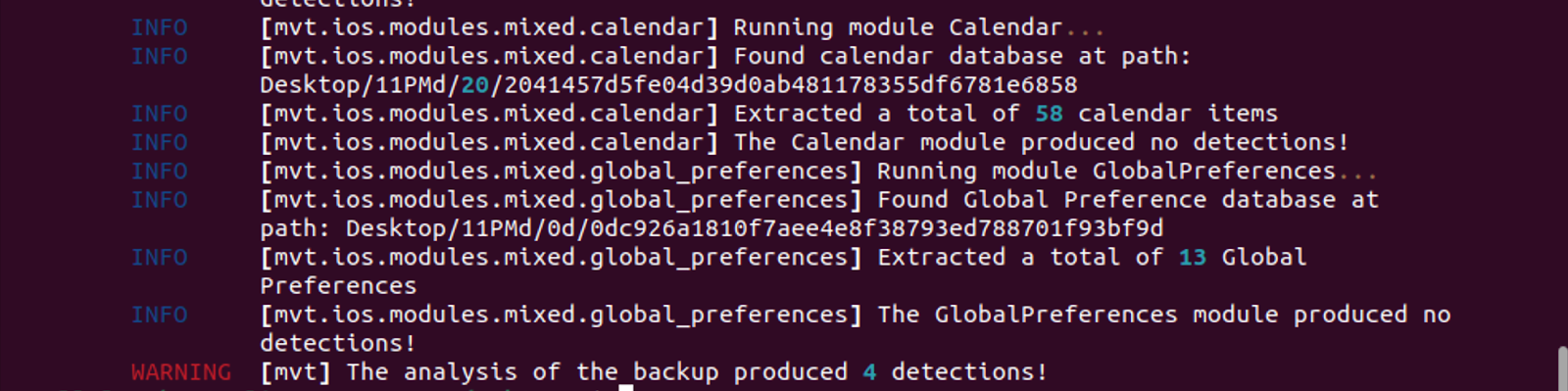

Image 2: The detected results are saved in separate files with “_detected” ending

If there are suspicions of spyware or malware without IOCs, but there are no detections, and a full file system dump isn’t feasible, users will need to work with the resources at hand. The most valuable files in the backup include:

Safari_history.json – check for any suspicious redirects and websites.

“url”: “http://yahoo.fr/”,

“visit_id”: 7,

“timestamp”: 726652004.790012,

“isodate”: “2024-01-11 07:46:44.790012”,

“redirect_source”: null,

“redirect_destination”: 8,

“safari_history_db”: “1a/1a0e7afc19d307da602ccdcece51af33afe92c53”

Datausage.json – check for suspicious processes.

“isodate”: “2023-12-14 03:05:02.321592”,

“proc_name”: “mDNSResponder/com.apple.datausage.maps”,

“bundle_id”: “com.apple.datausage.maps”,

“proc_id”: 69,

“wifi_in”: 0.0,

“wifi_out”: 0.0,

“wwan_in”: 3381.0,

“wwan_out”: 8224.0,

“live_id”: 130,

“live_proc_id”: 69,

“live_isodate”: “2023-12-14 02:45:10.343919”

Os_analytics_ad_daily.json – check for suspicious processes.

“ts”: “2023-07-11 05:24:31.981691”,

“wifi_in”: 400771.0,

“wifi_out”: 52607.0,

“wwan_in”: 0.0,

“wwan_out”: 0.0

Keeping a backup copy of a control device is required to maintain a record of the current names of legitimate processes within a specific iOS version. This control device can be completely reset and reconfigured with the same iOS version. Although annual releases often introduce significant changes, new legitimate processes may still be added, even within a year, through major system updates.

Sms.json – check for links, the content of these links, and domain information.

"ROWID": 97,

"guid": "9CCE3479-D446-65BF-6D00-00FC30F105F1",

"text": "",

"replace": 0,

"service_center": null,

"handle_id": 1,

"subject": null,

"country": null,

"attributedBody": "",

"version": 10,

"type": 0,

"service": "SMS",

"account": "P:+66********",

"account_guid": "54EB51F8-A905-42D5-832E-D98E86E4F919",

"error": 0,

"date": 718245997147878016,

"date_read": 720004865472528896,

"date_delivered": 0,

"is_delivered": 1,

"is_finished": 1,

"is_emote": 0,

"is_from_me": 0,

"is_empty": 0,

"is_delayed": 0,

"is_auto_reply": 0,

"is_prepared": 0,

"is_read": 1,

"is_system_message": 0,

"is_sent": 0,

"has_dd_results": 1,

"is_service_message": 0,

"is_forward": 0,

"was_downgraded": 0,

"is_archive": 0,

"cache_has_attachments": 0,

"cache_roomnames": null,

"was_data_detected": 1,

"was_deduplicated": 0,

"is_audio_message": 0,

"is_played": 0,

"date_played": 0,

"item_type": 0,

"other_handle": 0,

"group_title": null,

"group_action_type": 0,

"share_status": 0,

"share_direction": 0,

"is_expirable": 0,

"expire_state": 0,

"message_action_type": 0,

"message_source": 0,

"associated_message_guid": null,

"associated_message_type": 0,

"balloon_bundle_id": null,

"payload_data": null,

"expressive_send_style_id": null,

"associated_message_range_location": 0,

"associated_message_range_length": 0,

"time_expressive_send_played": 0,

"message_summary_info": null,

"ck_sync_state": 0,

"ck_record_id": null,

"ck_record_change_tag": null,

"destination_caller_id": "+66926477437",

"is_corrupt": 0,

"reply_to_guid": "814A603F-4FEC-7442-0CBF-970C14217E1B",

"sort_id": 0,

"is_spam": 0,

"has_unseen_mention": 0,

"thread_originator_guid": null,

"thread_originator_part": null,

"syndication_ranges": null,

"synced_syndication_ranges": null,

"was_delivered_quietly": 0,

"did_notify_recipient": 0,

"date_retracted": 0,

"date_edited": 0,

"was_detonated": 0,

"part_count": 1,

"is_stewie": 0,

"is_kt_verified": 0,

"is_sos": 0,

"is_critical": 0,

"bia_reference_id": null,

"fallback_hash": "s:mailto:ais|(null)(4)<7AD4E8732BAF100ABBAF4FAE21CBC3AE05487253AC4F373B7D1470FDED6CFE91>",

"phone_number": "AIS",

"isodate": "2023-10-06 00:46:37.000000",

"isodate_read": "2023-10-26 09:21:05.000000",

"direction": "received",

"links": [

"https://m.ais.co.th/J1Hpm91ix"

]

},

Sms_attachments.json – check for suspicious attachments.

"attachment_id": 4,

"ROWID": 4,

"guid": "97883E8C-99FA-40ED-8E78-36DAC89B2939",

"created_date": 726724286,

"start_date": "",

"filename": "~/Library/SMS/Attachments/b8/08/97883E8C-99FA-40ED-8E78-36DAC89B2939/IMG_0005.HEIC",

"uti": "public.heic",

"mime_type": "image/heic",

"transfer_state": 5,

"is_outgoing": 1,

"user_info": ",

"transfer_name": "IMG_0005.HEIC",

"total_bytes": 1614577,

"is_sticker": 0,

"sticker_user_info": null,

"attribution_info": null,

"hide_attachment": 0,

"ck_sync_state": 0,

"ck_server_change_token_blob": null,

"ck_record_id": null,

"original_guid": "97883E8C-99FA-40ED-8E78-36DAC89B2939",

"is_commsafety_sensitive": 0,

"service": "iMessage",

"phone_number": "*",

"isodate": "2024-01-12 03:51:26.000000",

"direction": "sent",

"has_user_info": true

}

Webkit_session_resource_log.json and webkit_resource_load_statistics.json – check for suspicious domains.

{

"domain_id": 22,

"registrable_domain": "sitecdn.com",

"last_seen": 1704959295.0,

"had_user_interaction": false,

"last_seen_isodate": "2024-01-11 07:48:15.000000",

"domain": "AppDomain-com.apple.mobilesafari",

"path": "Library/WebKit/WebsiteData/ResourceLoadStatistics/observations.db"

}

Tcc.json – check which applications have been granted which permissions.

"service": "kTCCServiceMotion",

"client": "com.apple.Health",

"client_type": "bundle_id",

"auth_value": "allowed",

"auth_reason_desc": "system_set",

"last_modified": "2023-07-11 06:25:15.000000"

To collect data about processes, users can use XCode Instruments.

Note: Developer mode must be enabled on the iOS device.

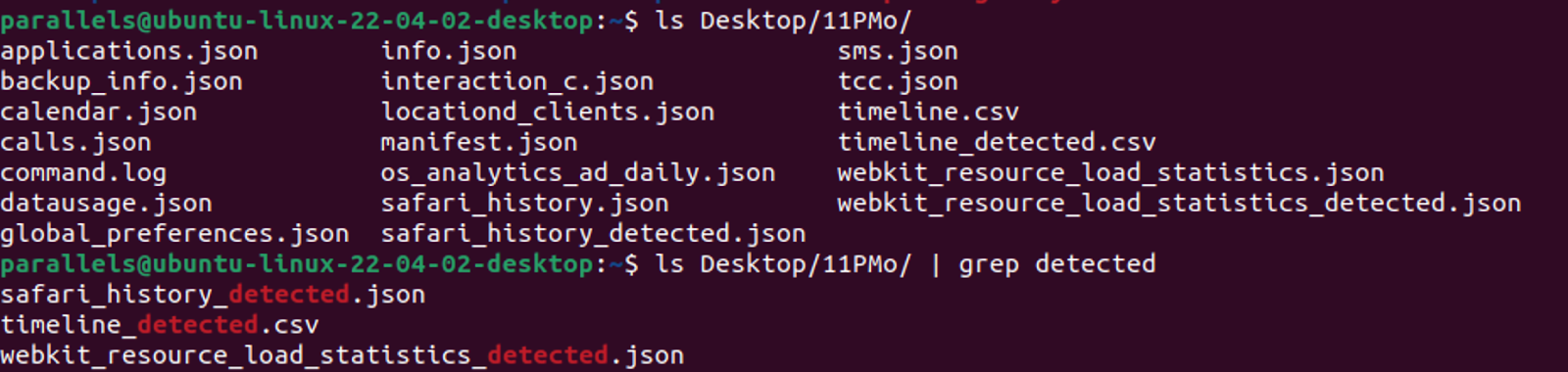

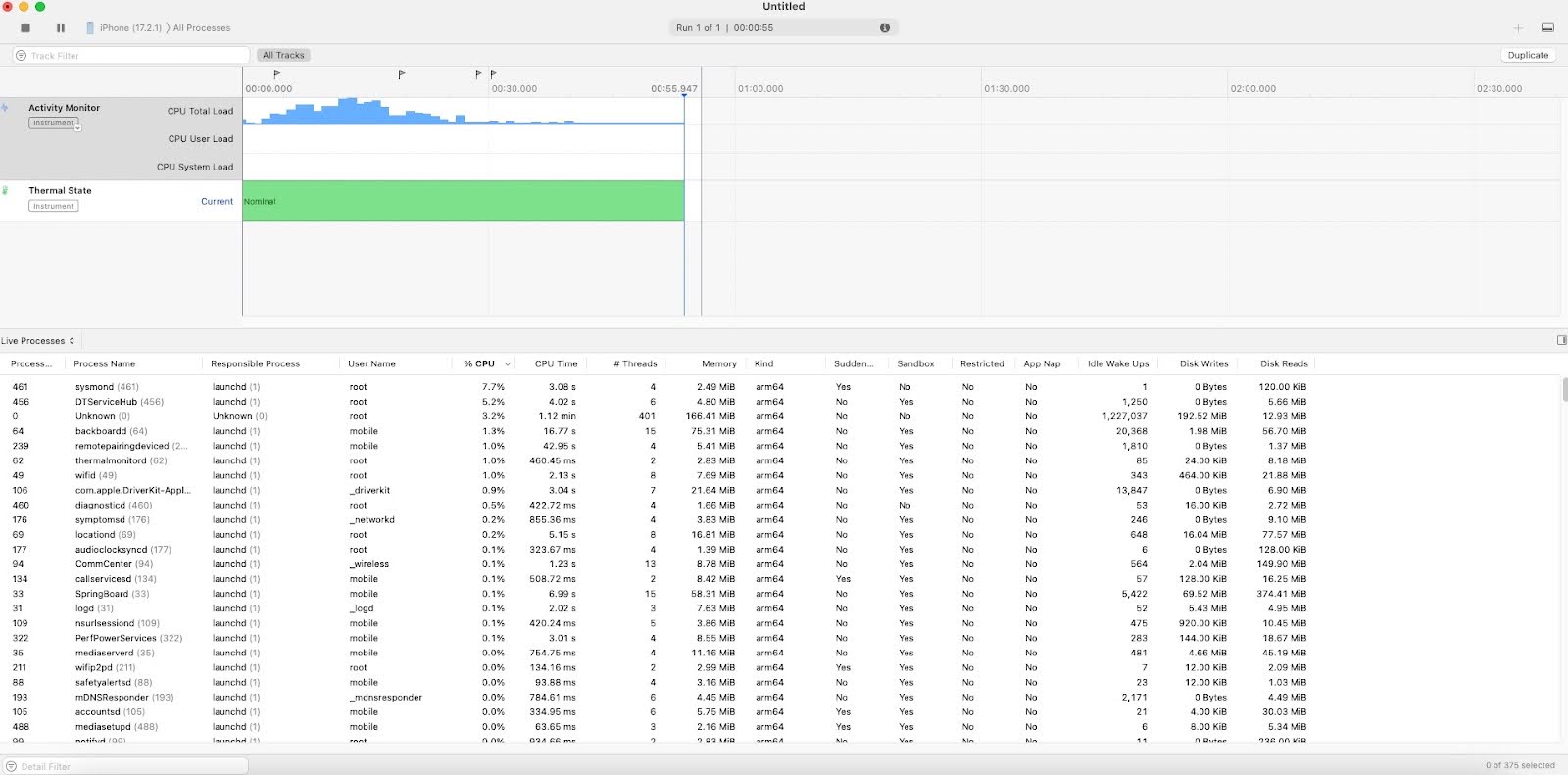

Image 3: Showcasing XCode instruments profile selection

Process data collection:

Image 4: Process list from iPhone

Overcoming the iOS interception challenge

For the common public

iOS security architecture typically prevents normal apps from performing unauthorized surveillance. However, a jailbroken device can bypass these security measures. Pegasus and other mobile malware may exploit remote jailbreak exploits to steer clear of detection by security mechanisms. This enables operators to install new software, extract data, and monitor and collect information from targeted devices.

Warning signs of an infection on the device include:

- Slower device performance

- Spontaneous reboots or shutdowns

- Rapid battery drain

- Appearance of previously uninstalled applications

- Unexpected redirects to unfamiliar websites

This reinstates the critical importance of maintaining up-to-date devices and prioritizing mobile security. Recommendations for end-users include:

- Avoid clicking on suspicious links

- Review app permissions regularly

- Enable Lockdown mode for protection against spyware attacks

- Consider disabling iMessage and FaceTime for added security

- Always install the updated version of the iOS

For businesses: Protect against Pegasus and other APT mobile malware

Securing mobile devices, applications, and APIs is crucial, particularly when they handle financial transactions and store sensitive data. Organizations operating in critical sectors, government, and other industries are prime targets for cyberattacks such as espionage and more, especially high-level employees.

Researching iOS devices presents challenges due to the closed nature of the system. Group-IB Threat Intelligence, however, helps organizations worldwide identify cyber threats in different environments, including iOS, with our recent discovery being GoldPickaxe.iOS – the first iOS Trojan harvesting facial scans and using them to potentially gain unauthorized access to bank accounts. Group-IB Threat Intelligence provides a constant feed on new and previously conducted cyber attacks, the tactics, techniques, and behaviors of threat actors, and susceptibility of attacks based on your organization’s risk profile— giving a clear picture of how your devices can be exploited by vectors, to initiate timely and effective defense mechanisms.

If you suspect your iOS or Android device has been compromised by Pegasus or similar spyware, turn to our experts for immediate support. To perform device analysis or set up additional security measures, organizations can also get in touch with Group-IB’s Digital Forensics team for assistance. source

HOW TO DEFEND YOURSELF AGAINST THE POWERFUL NEW NSO SPYWARE ATTACKS DISCOVERED AROUND THE WORLD

Even iPhones were vulnerable to the surveillance software, which appears to have been used against activists, journalists, and others.

AN INTERNATIONAL GROUP of journalists this month detailed extensive new evidence that spyware made by Israeli company NSO Group was used against activists, business executives, journalists, and lawyers around the world. Even Apple’s iPhone, frequently lauded for its tight security, was found to be “no match” for the surveillance software, leading Johns Hopkins cryptographer Matthew Green to fret that the NSO revelations had led some hacking experts to descend into a posture of “security nihilism.”

Security nihilism is the idea that digital attacks have grown so sophisticated that there’s nothing to be done to prevent them from happening or to blunt their impact. That sort of conclusion would be a mistake. For one thing, it plays into the hands of malicious hackers, who would love nothing more than for targets to stop trying to defend themselves. It’s also mistaken factually: You can defend yourself against NSO’s spyware — for example, by following operational security techniques like not clicking unknown links, practicing device compartmentalization (such as using separate devices for separate apps), and having a virtual private network, or VPN, on mobile devices. Such techniques are effective against any number of digital attacks and thus useful even if NSO Group turns out to be correct in its claim that the purported evidence against the company is not valid.

There may be no such thing as perfect security, as one classic adage in the field states, but that’s no excuse for passivity. Here, then, are practical steps you can take to reduce your “attack surface” and protect yourself against spyware like NSO’s.

Pegasus Offers “Unlimited Access to Target’s Mobile Devices”

The recent revelations concern a specific NSO spyware product known as Pegasus. They follow extensive prior studies of the company’s software from entities like the Citizen Lab, Amnesty International, Article 19, R3D, and SocialTIC. Here’s what we know about Pegasus specifically.

The software’s capabilities were outlined in what appears to be a promotional brochure from NSO Group dating to 2014 or earlier and made available when WikiLeaks published a trove of emails related to a different spyware firm, Italy’s Hacking Team. The brochure’s authenticity cannot be confirmed, and NSO has said it is not commenting further on Pegasus. But the document markets Pegasus aggressively, saying it provides “unlimited access to target’s mobile devices” and allows clients to “remotely and covertly collect information about your target’s relationships, location, phone calls, plans and activities — whenever and wherever they are.” The brochure also states the Pegasus can:

- Monitor voice and VoIP calls in real-time.

- Siphon contacts, passwords, files, and encrypted content from the phone.

- Operate as an “environmental wiretap,” listening through the microphone.

- Monitor communications through apps like WhatsApp, Facebook, Skype, Blackberry Messenger, and Viber.

- Track the phone’s location via GPS.

For all the hype, Pegasus is, however, just a glorified version of an old type of malware known as a Remote Access Trojan, or RAT: a program that allows an unauthorized party full access over a target device. In other words, while Pegasus may be potent, the security community knows well how to defend against this type of threat.

Let’s look at the different ways Pegasus can potentially infect phones — its various “agent installation vectors,” in the brochure’s own vernacular — and how to defend against each one.

Dodging Social Engineering Clickbait

There are numerous examples in reports of Pegasus attacks of journalists and human rights defenders receiving SMS and WhatsApp bait messages enjoining them to click malicious links. The links download spyware that lodges into devices through security holes in browsers and operating systems. This attack vector is called an Enhanced Social Engineer Message, or ESEM, in the leaked brochure. It states that “the chances that the target will click the link are totally dependent on the level of content credibility. The Pegasus solution provides a wide range of tools to compose a tailored and innocent message to lure the target to open the message.”

“The chances that the target will click the link are totally dependent on the level of content credibility.”

As the Committee to Protect Journalists has detailed, ESEM bait messages linked to Pegasus fall into various categories. Some claim to be from established organizations like banks, embassies, news agencies, or parcel delivery services. Others relate to personal matters, like work or alleged evidence of infidelity, or claim that the targeted person is facing some immediate security risk.

Future ESEM attacks may use different types of bait messages, which is why it’s important to treat any correspondence that tries to convince you to perform a digital action with caution. Here are some examples of what that means in practice:

- If you receive a message with a link, particularly if it includes a sense of urgency (stating a package is about to arrive or that your credit card is going to be charged), avoid the impulse to immediately click on it.

- If you trust the linked site, type out the link’s web address manually.

- If going to a website you frequently visit, save that website in a bookmark folder and only access the site from the link in your folder.

- If you decide you’re going to click a link rather than typing it out or visiting the site via bookmark, at least scrutinize the link to confirm that it is pointing to a website you are familiar with. And remember that it’s possible you will still be fooled: Some phishing links use similar-looking letters from a non-English character set, in what is known as a homograph attack. For example, a Cyrillic “О” might be used to mimic the usual Latin “O” we see in English.

- If the link appears to be a shortened URL, use a URL expander service such as URL Expander or ExpandURL to reveal the actual, long link it points to before clicking.

- Before you click a link apparently sent by someone you know, confirm that the person really did send it; their account may have been hacked or their phone number spoofed. Confirm with them using a different communication channel from the one on which you received the message. For instance, if the link came via a text or email message, give the sender a call. This is known as out-of-band verification or authentication.

- Practice device compartmentalization, using a secondary device without any sensitive information on it to open untrusted links. Keep in mind that if the secondary device is infected, it may still be used to monitor you via the microphone or camera, so keep it in a Faraday bag when not in use — or at least away from where you have sensitive conversations (a good idea even if it’s in a Faraday bag).

- Use nondefault browsers. According to a section titled “Installation Failure” in the leaked Pegasus brochure, installation may fail if the target is running an unsupported browser and in particular a browser other than “the default browser of the device.” But the document is now several years old, and it is possible that Pegasus today supports all kinds of browsers.

- If there is ever any doubt about a given link, the safest operational security measure is to avoid opening the link.

Thwarting Network Injection Attacks

Another way Pegasus infected devices in multiple cases was by intercepting a phone’s network traffic using what’s known as a man-in-the-middle, or MITM, attack, in which Pegasus intercepted unencrypted network traffic, like HTTP web requests, and redirected it toward malicious payloads. Pulling this off entailed either tricking the phone into connecting to a rogue portable device which pretends to be a cell tower nearby or gaining access to the target’s cellular carrier (plausible if the target is in a repressive regime where the government provides telecommunication services). This attack worked even if the phone was in mobile data-only mode, and not connected to Wi-Fi.

When Maati Monjib, the co-founder of the Freedom Now NGO and the Moroccan Association for Investigative Journalism, opened the iPhone Safari browser and typed yahoo.fr, Safari first tried going to http://yahoo.fr. Normally this would have redirected to https://fr.yahoo.com, an encrypted connection. But since Monjib’s connection was being intercepted, it instead redirected to a malicious third-party site which ultimately hacked his phone.

Typing just the website domain into a browser opens you to attacks, because your browser will attempt an unencrypted connection to the site.

Typing just the website domain (such as yahoo.fr) into a browser address bar without specifying a protocol (such as https://) opens the possibility for MITM attacks, because your browser by default will attempt an unencrypted HTTP connection to the site. Usually, you reach the genuine site, which immediately redirects you to a safe HTTPS connection. But if someone is tracking to hack your device, that first HTTP connection is enough of an opening to hijack your connection.

Some websites protect against this using a complicated security feature known as HTTP Strict Transport Security, which prevents your browser from ever making an unencrypted request to them, but you can’t always count on this, even for some websites that implement it correctly.

Here are some things you can do to prevent these kinds of attacks:

- Always type out https:// when going to websites.

- Bookmark secure (HTTPS) URLs for your favorite sites, and use those instead of typing the domain name directly.

- Alternately, use a VPN on both your desktop and mobile devices. A VPN tunnels all connections securely to the VPN server, which then accesses websites on your behalf and relays them back to you. This means that an attacker monitoring your network will likely not be able to perform a successful MITM attack as your connection is encrypted to the VPN — even if you type a domain directly into your browser without the “https://” part.

If you use a VPN, keep in mind that your VPN provider has the ability to spy on your internet traffic, so it’s important to pick a trustworthy one. Wirecutter publishes a regularly updated, thorough comparison of VPN providers based on their history of third-party security audits, their privacy and terms of use policies, the security of the VPN technology used, and other factors.

Zero-Click Exploits

Unlike infection attempts which require that the target perform some action like clicking a link or opening an attachment, zero-click exploits are so called because they require no interaction from the target. All that is required is for the targeted person to have a particular vulnerable app or operating system installed. Amnesty International’s forensic report on the recently revealed Pegasus evidence states that some infections were transmitted through zero-click attacks leveraging the Apple Music and iMessage apps.

Your device should have the bare minimum of apps that you need.

This is not the first time NSO Group’s tools have been linked to zero-click attacks. A 2017 complaint against Panama’s former President Ricardo Martinelli states that journalists, political figures, union activists, and civic association leaders were targeted with Pegasus and rogue push notifications delivered to their devices, while in 2019 WhatsApp and Facebook filed a complaint claiming NSO Group developed malware capable of exploiting a zero-click vulnerability in WhatsApp.

As zero-click vulnerabilities by definition do not require any user interaction, they are the hardest to defend against. But users can reduce their chances of succumbing to these exploits by reducing what is known as their “attack surface” and by practicing device compartmentalization. Reducing your attack surface simply means minimizing the possible ways that your device may be infected. Device compartmentalization means spreading your data and apps across multiple devices.

Specifically, users can:

- Reduce the number of apps on your phone. The fewer unlocked doors your home has, the fewer opportunities a burglar has to enter; similarly, fewer apps means fewer virtual doors on your phone for an adversary to exploit. Your device should have the bare minimum apps that you need to perform day-to-day function. There are some apps you cannot remove, such as iMessage; in those cases you can often disable them, though doing so will also make text messages no longer work on your iPhone.

- Regularly audit your installed apps (and their permissions), and remove any that you no longer need. It is safer to remove a seldom-used app and download it again when you actually need it than to let it remain on your phone.

- Regularly update both your phone’s operating system and individual apps, since updates close vulnerabilities, sometimes even unintentionally.

- Compartmentalize your remaining apps. If a phone only has WhatsApp installed and is compromised, the hacker will get WhatsApp data, but not other sensitive information like email, calendar, photos, or Signal messages.

- Even a compartmentalized phone can still be used as a wiretap and a tracking device, so keep devices physically compartmentalized — that is, leave them in another room, ideally in a tamper bag.

Physical Access

A final way an attacker can infect your phone is by physically interacting with it. According to the brochure, “when physical access to the device is an option, the Pegasus agent can be manually injected and installed in less than five minutes” — though it is unclear if the phone needs to be unlocked or if attackers are able to infect even a PIN-protected phone.

There seem to be no known cases of physically launched Pegasus attacks, though such exploits may be difficult to spot and distinguish from online attacks. Here’s how you can mitigate them:

- Always maintain a line of sight to your devices. Losing sight of your devices opens the possibility of physical compromise. Obviously there is a difference between a customs agent taking your phone at the airport versus you leaving your laptop behind in a room in your residence when you go to the bathroom, but all involve some risk, and you will have to calibrate your own risk tolerance.

- Put your device in a tamper bag when it needs to be left unattended, particularly in riskier locations like hotel rooms. This will not prevent the device from being manipulated but will at the least provide a ready alert that the device has been taken out of the bag and might have been tampered with, at which point the device should no longer be used.

- Use burner phones and other compartmented devices when entering potentially hostile environments such as government buildings, including embassies and consulates, or when going through border checkpoints.

Generally:

- Use Amnesty International’s Mobile Verification Toolkit if you suspect your phone is infected with Pegasus.

- Regularly back up important files.

- And finally, there’s no harm in regularly resetting your phone.

Although Pegasus is a sophisticated piece of spyware, there are tangible steps you can take to minimize the chance that your devices will be infected. There’s no foolproof method to eliminate your risk entirely, but there are definitely things you can do to lower that risk, and there’s certainly no need to resort to the defeatist view that we’re “no match” for Pegasus. source

How to Check if Your Cellphone Is Infected With Pegasus Spyware

NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware can turn any infected smartphone into a remote microphone and camera, spying on its own owner while also offering the hacker – usually in the form of a state intelligence or law enforcement agency – full access to files, messages and, of course, the user’s location.

Pegasus is one of a number of proprietary tools sold as part of the hacker-for-hire industry – and one found at the very high-end of that dark market. Other companies offer less expensive services – for example, only providing geolocation services for its clients. So how can you protect yourself? And how can you check to see if your phone has been targeted in the past or is infected now?

Haaretz offers a simple, nontechnical explanation on how to check and stay safe…

The weakest link

Most cellphone spyware operates in a similar fashion: a message is sent to a phone with a nefarious message. The message usually contains a link that will either download the malware onto your device directly, or refer it to a website that will prompt a download – all unbeknown to the phone’s owner.

There are other ways to get your phone to download something that don’t involve a message. However, from the moment of infection, most spyware tools follow a similar protocol: once installed, the spyware contacts what is called a “command-and-control” server, which provides it with instructions remotely.

“Let’s say the Israel Police are the ones who installed Pegasus on your smartphone and they want to know where you – or, more precisely, your phone – has been in the previous 24 hours. To get that information, instructions to obtain that data are sent to a C&C server connected to the phone,” explains Dr. Gil David, a researcher and cybersecurity consultant.

Many times, the links sent to you will appear innocent. It may look like a message from the Post Office or Amazon. But don’t be fooled: Through some simple social engineering and a process called “DNS spoofing,” even an official-looking URL may be a trap.

Sadly, staying safe is not always possible.

What makes Pegasus so expensive is its ability to not just potentially infect any smartphone selected for targeting remotely, but to do so with a “zero click” infection. This means your phone can be infected without you even having to click on a link – for example, with the code instructing your phone to reach out to the server secretly encoded into a WhatsApp message or even in a file like a photo texted to you via iMessage.

These “zero click” attacks make use of what is called “zero-day” exploits: unknown loopholes in your phone’s defenses that allow these hidden bits of code to kick into action without the victim doing anything.

So, another good practice is to make sure your phone’s operating system is as updated as possible: As new exploits are discovered, they are quickly “patched” by the likes of Apple and Google.

According to digital forensics experts Amnesty International and Citizen Lab, Pegasus’ zero click infections have only been found on iPhones. “Most recently, a successful ‘zero-click’ attack has been observed exploiting multiple zero-days to attack a fully patched iPhone 12 running iOS 14.6 in July 2021,” Amnesty notes in its instructive report “How to Catch NSO Group’s Pegasus.”

It seems Pegasus’ ability to infect iPhones was based on a previously unknown loophole in the iMessage service, and this too has subsequently been patched. However, other Israel firms, for instance QuadDream, reportedly have such abilities as well.

“From 2019, an increasing amount of vulnerabilities in iOS, especially iMessage and FaceTime, started getting patched thanks to their discoveries by vulnerability researchers, or to cybersecurity vendors reporting exploits discovered in-the-wild,” Amnesty writes – so make sure your phone is updated.

Indicators of compromise

Groups like Amnesty and Citizen Lab find NSO’s spyware on phones using two different methods. Both involve searching for what is termed “indicators of compromise,” or IOCs.

Amnesty maintains a database of nefarious domains used by NSO’s clients. The list is constantly updating as more bogus URLs are found. Citizen Lab, meanwhile, also maintains a database of so-called vectors: messages sent to victims containing nefarious code or URLS. The two groups each maintain updated lists of Pegasus’ related processes that together permit attribution.

The only thing that has changed with Pegasus over the years is the way your phone is referred to the server, and the way the so-called payload is delivered.

“While SMS messages carrying malicious links were the tactic of choice for NSO Group’s customers between 2016 and 2018, in more recent years they appear to have become increasingly rare,” Amnesty wrote in its July 2021 report.

The newer trend, discovered in the case of Moroccan journalist Omar Radi, who was infected with Pegasus in 2020, is what is known as “packet injection.” This means that the download order is delivered not through a message but instead through your network, in the form of a hidden command “injected” into the phone through what Amnesty describes as “tactical devices, such as rogue cell towers, or through dedicated equipment placed at the mobile operator.

“The discovery of network injection attacks in Morocco signaled that the attackers’ tactics were indeed changing. Network injection is an effective and cost-efficient attack vector for domestic use especially in countries with leverage over mobile operators,” it explained.

As NSO’s clients are state agencies, they can easily make use of the mobile infrastructure to infect phones.

Therefore, and though such injection infections can also be forced upon you, other good practices include never using free Wi-Fi; never connecting to wireless networks you do not absolutely know are secure – as these networks can easily be hacked so they infect your phone and refer it to the snooping server. Not using so-called VPNs is also advisable for the same reason.

Chances are you have not been infected with Pegasus. However, if you have cause for concern and are scared you are or were infected, there are a few options: Amnesty offers a useful, free and open source tool called the Mobile Verification Toolkit that can check a backup of your device or its logs for any IOC. The MVT will scan your iPhone’s logs for Pegasus-related processes or search your Android’s messages for nefarious links. The tool can be downloaded here. The bad news is that it requires some technical know-how and is currently devoid of a simple-to-use interface. To get it to work, you first need to make a specific type of backup of your phone, and then you need to download the program and run the code on your computer so it can scan the file you created. Running the program requires you to download Python. Luckily, the tool comes with very clear instructions, and even those unskilled in code can make use of it with a bit of effort. Furthermore, it also allows you to conduct the test yourself. A similar product is iMazing, a phone-backup platform that runs on your desktop and provides a MVT-like analysis of your device. It does not prevent infections but can check your phone for IOCs. If the best offense is defense, there’s also a growing cellphone security market. Cyberdefense firms like ZecOps offer organizations like the BBC and Fortune 2000 companies a platform that inspects phones for current infections or traces of historic attacks. ZecOps also provides this service pro bono for journalists involved in the Pegasus Project. Private users can also buy such services. For example, the Israeli-Indian security firm SafeHouse Technologies offers an app called “BodyGuard” that provides defenses for your phone, for a small price. It already has more than a million users, mostly in India. If you can’t get the Mobile Verification Toolkit to work and are reluctant to use an app, and you genuinely fear you have been targeted, you can also drop us a tip here and we at Haaretz will get you checked. source

HOW TO DETECT PEGASUS SPYWARE

As one of the leading commercial spyware programs, Pegasus has been used by a host of companies, governments, and other entities to collect sensitive data from individuals’ smartphones. If Pegasus is deployed on your smartphone, your sensitive data could be at risk.

Read on to learn how to detect Pegasus spyware on your smartphone.

How to Detect Pegasus Spyware on Your Smartphone

The data privacy demands of today’s IT landscape call for robust mobile security, as more individuals rely on smartphone applications for essential day-to-day tasks.

Safeguarding your smartphone data from threats like Pegasus starts with knowing how to:

- Scan for and detect Pegasus spyware on your smartphone

- Identify Pegasus spyware installed on your smartphone

- Remove Pegasus spyware from your Android or iPhone

- Prevent Pegasus spyware from compromising your smartphone data

Dealing with advanced mobile security risks like Pegasus spyware is much easier with the help of a managed security services provider (MSSP), who can advise on how to detect pegasus spyware on iPhone or Android.

What is Pegasus Spyware?

Developed by the NSO group in Israel, Pegasus is signature spyware that has been implicated in the secret surveillance of individuals worldwide. Pegasus spyware is considered dangerous because it allows an attacker to control a victim’s smartphone.

Using Pegasus spyware, a perpetrator can:

- Wiretap and listen to conversations

- Access photos and videos

- Control applications on a smartphone

It is difficult and often impossible for antivirus solutions to detect Pegasus spyware because it exploits zero-day vulnerabilities, which are unknown to the developers of these solutions.

How to Detect Pegasus Spyware

Over years of extensive research, Amnesty International has developed a methodology to detect Pegasus spyware on smartphones, providing it to the public as a resource on Github.

Using Amnesty International’s methodology, you can find a list of:

- Domain names of Pegasus infrastructure

- Email addresses identified in previous attacks

- Process names associated with Pegasus

Beyond the indicators of Pegasus compromise methodology, Amnesty International also released a Mobile Verification Toolkit (MVT) to help support users interested in detecting Pegasus spyware on their smartphones. With the help of Amnesty International’s spyware detection tools, you can learn how to detect pegasus spyware on Android or iPhone.

How to Detect Pegasus Spyware on iOS

Here’s how to check for pegasus spyware on iOS devices such as iPhones:

- Create a backup of encrypted data on a device other than your smartphone

- Once your smartphone is securely backed up, download the MVT tool onto your iPhone and follow Amnesty International’s instructions for detecting Pegasus.

Whereas other apps can detect Pegasus on iOS, it’s best to follow Amnesty International’s instructions or work with a qualified MSSP to avoid running into any issues while detecting the spyware.

How to Detect Pegasus Spyware on Android

Although the MVT mostly caters to iOS devices, it can still detect Pegasus on Android.

If you are wondering how to detect Pegasus spyware on Android with the MVT, the first places to start looking are potentially malicious text messages and APKs on your smartphone.

How Pegasus Works

For most Pegasus infections, the spyware is installed remotely on victims’ smartphones. However, Pegasus can be installed physically, and, in some cases, it can use the victim’s smartphone for data storage prior to transmitting data to a remote server.

Pegasus Remote Installation

Pegasus spyware can be remotely installed on a smartphone via:

- Zero-click attacks – Zero-click exploits typically leverage applications such as Apple Music or iMessage to send requests to the victim’s smartphone. Here, the victim does not interact with the spyware and is clueless about the download of Pegasus spyware.

- Malicious text messages – A victim receives a text message containing an exploit link for a Pegasus spyware download. Clicking the link deploys spyware on the victim’s smartphone.

- Network injection attack – While browsing the Internet, a victim is redirected from a clear-text HTTP website to a decoy of a legitimate business. Unknowingly, a victim may then provide access credentials or other sensitive information.

In most cases, remote installation of Pegasus spyware on victims’ phones via zero-click attacks leverages zero-day vulnerabilities, of which the smartphone manufacturer may not be aware.

This makes Pegasus spyware very dangerous to its victims, who may not realize their sensitive data is being surveilled until it is too late.

Pegasus Physical Installation

While it is uncommon, Pegasus can be installed by connecting a victim’s smartphone to another device such as a computer to deploy the spyware. However, this would involve the difficult task of accessing a victim’s smartphone without their knowledge.

Pegasus Data Management

According to NSO, the spyware will transmit data from a victim’s smartphone to a server where the attacker can access the data. However, if Pegasus is unable to send data to a server, it will transmit the data to a “hidden and encrypted buffer” within the phone’s storage.

What Data Can Pegasus Access?

Once deployed on a smartphone, Pegasus spyware can access a range of data, including:

- Text messages

- Emails

- Photos and videos

- Personal contacts

- Location

- Audio messages and recordings

Detecting Pegasus spyware on your smartphone is critical to minimizing the risks of your sensitive data being exposed by perpetrators.

Can Pegasus be Removed?

You can remove Pegasus from your smartphone by attempting the following actions:

- Restarting your smartphone, to put a temporary stop to Pegasus

- Resetting your smartphone to its factory settings, which may remove Pegasus

- Updating your smartphone’s system software and apps to current versions

- Removing any unknown device connections to social media platforms

When removing Pegasus from your smartphone, it is always best to work with the MVT resource provided by Amnesty International. If Pegasus spyware removal becomes difficult, consider consulting an MSSP for help.

What to Do if You Have Pegasus

According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), here’s what to do if you have Pegasus:

- Buy a new smartphone and stop using the one infected with Pegasus, ensuring the compromised smartphone is not close to you or your work environment.

- Change passwords for all accounts on the new smartphone and remember to sign out of the accounts on the compromised one.

If you have Pegasus, it is best to contact an experienced MSSP, who will point you to Pegasus spyware removal tools that will help remove Pegasus and keep your data safe.

Other Spyware like Pegasus

Besides Pegasus, other types of spyware include:

- Trojans, which can steal a victim’s funds or credentials to make fraudulent purchases.

- Stealware, which can intercept traffic from online shopping sites like those offering credits or rewards for purchases.

With everyone using smartphones or tablets to store sensitive information like account passwords, securing these devices from spyware and other forms of malware is paramount.

In an organizational setting, it is critical for leadership to emphasize the importance of mobile security in defending sensitive data stored on smartphones from various types of spyware.

How to Protect From Pegasus and Other Spyware

Protecting your organization from Pegasus and other spyware revolves around implementing mobile device security best practices such as:

- Encrypting any communication of sensitive data with industry-standard algorithms

- Keeping up-to-date with the latest phishing and malware attempts

- Updating your smartphone or mobile device with the latest security patches

- Using strong passwords and multi-factor authentication on all mobile devices

- Conducting routine penetration testing on mobile devices that contain sensitive data

If you are wondering how to block Pegasus spyware, some of the mobile security best practices above can help. However, it’s best to implement them with the guidance of a leading MSSP. source

Journalists, lawyers and activists hacked with Pegasus spyware in Jordan, forensic probe finds

de Pegasus spyware was used in Jordan to hack the cellphones of at least 30 people, including journalists, lawyers, human rights and political activists, the digital rights group Access Now said Thursday.

The hacking with spyware made by Israel’s NSO Group occurred from 2019 until last September, Access Now said in its report. It did not accuse Jordan’s government of the hacking.

One of the targets was Human Rights Watch’s deputy director for the region, Adam Coogle, who said in an interview that it was difficult to imagine who other than Jordan’s government would be interested in hacking those who were targeted.

The Jordanian government had no immediate comment on Thursday’s report.

In a 2022 report detailing a much smaller group of Pegasus victims in Jordan, digital sleuths at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab identified two operators of the spyware it said may have been agents of the Jordanian government. A year earlier, Axios reported on negotiations between Jordan’s government and NSO Group.

“We believe this is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the use of Pegasus spyware in Jordan, and that the true number of victims is likely much higher,” Access Now said. Its Middle East and North Africa director, Marwa Fatafta, said at least 30 of 35 known targeted individuals were successfully hacked.

Citizen Lab confirmed all but five of the infections, with 21 victims asking to remain anonymous, citing the risk of reprisal. The rest were identified by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International’s Security Lab, and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

NSO Group says it only sells to vetted intelligence and law enforcement agencies — and only for use against terrorists and serious criminals. But cybersecurity researchers who have tracked the spyware’s use in 45 countries have documented dozens of cases of politically motivated abuse of the spyware — from Mexico and Thailand to Poland and Saudi Arabia.

An NSO Group spokesperson said the company would not confirm or deny its clients’ identities. NSO Group says it vets customers and investigates any report its spyware has been abused.

The U.S. government was unpersuaded and blacklisted the NSO Group in November 2021, when iPhone maker Apple Inc. sued it, calling its employees “amoral 21st century mercenaries who have created highly sophisticated cyber-surveillance machinery that invites routine and flagrant abuse.”

Those targeted in Jordan include Human Rights Watch’s senior researcher for Jordan and Syria, Hiba Zayadin. Both she and Coogle had received threat notifications from Apple on Aug. 29 that state-sponsored attackers had attempted to compromise their iPhones.

Coogle’s local, personal iPhone was successfully hacked in October 2022, he said, just two weeks after the human rights group published a report documenting the persecution and harassment of citizens organizing peaceful political dissent.

After that, Coogle activated “Lockdown Mode,” on the iPhone, which Apple recommends for users at high risk.

Human Rights Watch said in a statement Thursday that it had contacted NSO Group about the attacks and specifically asked it to investigate the hack of Coogle’s device “but has received no substantive response to these inquiries.”

Jordanian human rights lawyer Hala Ahed — known for defending women’s and workers rights and prisoners of conscience — was also targeted at least twice by Pegasus, successfully in March 2021 then unsuccessfully in February 2023, Access Now said.

About half of those found to have been targeted by Pegasus in Jordan — 16 in all — were journalists or media workers, the report said.

One veteran Palestinian-American journalist and columnist, Dauod Kuttab, was hacked with Pegasus three times between February 2022 and September 2023.

Along the way, he said, he’s learned important lessons about not clicking on links in messages purporting to be from legitimate contacts, which is how one of the Pegasus hacks snared him.

Kuttab refused to speculate about who might have targeted him.

“I always assume that somebody is listening to my conversations,” he said, as getting surveilled “comes with the territory” when you are journalist in the Middle East.

But Kuttab does worry about his sources being compromised by hacks — and the violation of his privacy.

“Regardless of who did it, it’s not right to intervene into my personal, family privacy and my professional privacy.” source

The NSO File: A Complete (Updating) List of Individuals Targeted With Pegasus Spyware

The Israeli-made Pegasus spyware is suspected of infecting over 450 phones targeted by clients of NSO, who range from Saudi Arabia to Mexican drug lords. Here’s a list of the confirmed Pegasus victims.

The Israeli-made Pegasus spyware, sold by the cyberoffense firm NSO to state intelligence agencies around the world, has become infamous in recent years. Exploiting unknown loopholes in WhatsApp, iMessage and Android has allowed the group’s clients to potentially infect any smartphone and gain full access to it – in some cases without the owner even clicking or opening a file.

Digital forensics groups such as Amnesty International and the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab have revealed numerous potential targets with traces of the spyware on their phones. Last summer, Project Pegasus – led by Paris-based NGO Forbidden Stories with the help of Amnesty’s Security Lab – organized an international consortium of journalists, including Haaretz and its sister publication TheMarker, to investigate thousands of additional potential targets selected for possible surveillance by NSO Group clients worldwide.

So far, targets have been found across the world: from India and Uganda to Mexico and the West Bank, with high-profile victims including U.S. officials and a New York Times journalist.

Now, for the first time, Haaretz has assembled a list of confirmed cases involving Pegasus spyware.

Though there have been over 450 suspected hacking cases, this list, which was put together with the help of Amnesty’s Security Lab, includes only the cases in which infections were confirmed either by Amnesty or another digital forensics group like Citizen Lab (which also helped construct this list). It also includes a few instances where official bodies such as French intelligence agencies or private firms like Apple or WhatsApp have publicly confirmed attacks.

The list does not include those suspected of being targeted – for example, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, who was reportedly sent the spyware via a WhatsApp message from no less than Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Rather, it is those who have actually been found with Pegasus on their phones.

The NSO Group, which refuses to confirm the identity of its clients and claims it has no knowledge of their targets, has denied most of these cases and says digital forensic analysis cannot fully identify its software.

- How to Check if Your Cellphone Is Infected With Pegasus Spyware

- Police Use NSO’s Pegasus to Spy on Israelis Without Warrant, Report Says

- Israeli NSO Spyware Found on Phones of Jordanian, Bahraini Women’s Rights Activists

The gap between the massive list of potential targets and those who were actually infected highlights how hard it is to confirm the presence of Pegasus spyware on phones. For instance, a private investigation commissioned by Bezos himself found that his phone had received a strange message from Crown Prince Mohammed, after which the tycoon’s device began sending out a lot of data. However, Bezos was reluctant to hand his phone over to anyone other than the handpicked investigators he had hired; they said it was very likely his phone had been infected.

Here is the list of most, if not all, known and confirmed Pegasus cases. They are sorted by the nationality of the victims or their country of residence when they were targeted.

The list of confirmed cases is followed by an additional list of names of those who have been confirmed to have been targeted but whose actual infection has not been verified.

AZERBAIJAN

Khadija Ismayilova

The Azerbaijani investigative journalist based in Baku was targeted repeatedly for over three years as part of government persecution as a result of her work, the Project Pegasus investigation revealed.

Sevinc Vaqifqizi

Freelance Azerbaijanii journalist Vaqifqizi was found by Amnesty and Forbidden Stories to have had their phone infected with Pegasus in 2019 and 2020.

BAHRAIN

Moosa Abd-Ali

Moosa Abd-Ali is a Bahraini activist living in exile in London who was found to have been targeted in the past, with the Bahraini government hacking his personal computer in 2011. According to Citizen Lab, Abd-Ali’s iPhone 8 appears to have been hacked with Pegasus at some point prior to September 2020.

Yusuf al-Jamri

A Bahraini blogger who says he was tortured by his government, Yusuf al-Jamri was granted asylum in the U.K. in 2018. According to Citizen Lab, Jamri’s iPhone 7 appears to have been hacked with Pegasus at some point prior to September 2019.

Seven rights activists

At least three members of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, another three from the nonprofit Waad and one from the group Al Wefaq were also infected, Citizen Lab found. At least another seven members of BCHR and the other groups were actually targeted, but their infection was not confirmed by Citizen Lab.

EL SALVADOR

Carlos Martínez

A reporter for El Faro, he was one of over 35 journalists and members of civil society groups infected by the Pegasus spyware between July 2020 and November 2021.

Daniel Lizárraga

A Mexican journalist and the editor of El Faro, who was expelled from El Salvador. Citizen Lab found that his phne had been infected.

Nine El Faro journalists

The following journalists with El Faro were all found by Citizen Lab to have been infected by the Pegasus spyware: Gabriela Cáceres, Carlos Dada, Carlos Ernesto Martínez D’aubuisson, Julia Gavarrete (who had two phones hacked), Valeria Guzmán, Ana Beatriz Lazo, Rebeca Monge, Víctor Peña, Nelson Rauda.

El Salvadorian journalists

Citizen Lab discovered that the following journalists were also infected with Pegasus: Efren Lemus, Gabriel Labrador, José Luis Sanz, María Luz Nóchez, Mauricio Ernesto Sandoval Soriano, Óscar Martínez, Roman Gressier, Roxana Lazo, Sergio Arauz, Beatriz Benitez, Ezequiel Barrera, Xenia Oliva, an unnamed journalist from Diario El Mundo, and Daniel Reyes.

Noah Bullock

The head of Cristosal, a human rights organization based in El Salvador, who was also found by Citizen Lab to have been infected.

Ricardo Avelar

A journalist with El Diario de Hoy, Citizen Lab confirmed that his device had been infected.

Jose Marinero

An official with the activism group Fundación DTJ in El Salvador whose phone was found by Citizen Lab to have been infected.

Xenia Hernandez

Another official with the activism group Fundación DTJ in El Salvador whose phone was found by Citizen Lab to have been infected.

Oscar Luna

An activist with the digital rights group Revista Digital Disruptiva. Citizen Lab found that their phone had been infected.

Mariana Belloso

An independent journalist whose phone was found by Citizen Lab to have been infected by the Pegasus spyware.

Carmen Tatiana Marroquín

An economist and columnist whose phone was found by Citizen Lab to have been infected by the Pegasus spyware.

FINLAND

Finnish diplomats

An unknown number of Finnish diplomats stationed abroad were found to have been infected, the Finnish Foreign Ministry confirmed. Their identity was not disclosed, nor was the suspected operator.

FRANCE

Bruno Delport

The phone of the director of Parisian radio station TSF Jazz was found by Citizen Lab to have been infected in 2019, just as he was applying for the presidency of Radio France.

Lénaïg Bredoux

The investigative journalist and general editor of Mediapart was confirmed to have been infected by Pegasus. The confirmation was made by France’s computer security agency following Project Pegasus. Bredoux was involved in a story about the head of Morocco’s intelligence agency, a known NSO client.

Edwy Plenel

The investigative journalist with Mediapart was confirmed to have been infected by Pegasus. The confirmation was made by France’s computer security agency following Project Pegasus.

Unnamed France 24 journalist

A senior journalist with France 24 was confirmed to have been infected by Pegasus in May 2019, September 2020 and January 2021. That was confirmed by France’s computer security agency after Project Pegasus.

Claude Mangin

French national whose husband, Naama Asfari, is jailed in Morocco for advocating for Western Saharan independence. As part of Project Pegasus, it was found that at least two of her phones were infected.

Arnaud Montebourg

A former minister in the government of Manuel Valls, Montebourg was targeted in 2019, most likely by Morocco, an analysis by Amnesty found. Montebourg has given testimony to ANSSI and its investigation into NSO in France.

Suspected operator: Morocco

HUNGARY

Dániel Németh

A Hungarian photojournalist involved in covering President Viktor Orbán and the country’s elites, two of his phones were infected in 2021. Direkt36, working with Citizen Lab and Amnesty’s Security Lab, confirmed the infections.

Zoltán Páva

The former Hungarian politician, now the publisher of an opposition news website, was also infected by Pegasus in March and May 2021.

Adrien Beauduin

A gender studies student at Central European University in Hungary, Beauduin was confirmed to have had his phone infected after being arrested in a protest against Orbán’s policies.

Szabolcs Panyi

The journalist with Direkt36, which was a partner in the Pegasus Project, was infected a number of times in 2019. The confirmation was made by Amnesty as part of the global investigation.

András Szabó

An investigative journalist with Direkt36, Szabó’s phone was infected a number of times in 2019. The confirmation was made by Amnesty as part of the global investigation.

Brigitta Csikász

A Hungarian journalist covering crime stories, Csikász’s phone was infected in 2019 – which was confirmed by Direkt36 and Amnesty.

INDIA

Jagdeep Singh Randhawa

Human rights lawyer and activist from Punjab had his phone hacked in July and August 2019.

Mangalam Kesavan Venu

Founding editor of The Wire – a nonprofit Indian investigative journalism outlet that was part of the Project Pegasus investigation – was found to have been infected with the spyware.

Paranjoy Guha Thakurta

Investigative journalist who was looking into how the Modi government used Facebook to spread disinformation; Amnesty confirmed his phone had been infected by NSO’s spyware as part of the Project Pegasus investigation.

Prashant Kishor

Political pollster working with a number of opposition parties in India, his phone was infected in 2018, Amnesty confirmed, months before an election – in what critics say was an attempt by Modi’s party to use the spyware to collect political information.

Rona Wilson

An activist focused on minorities and prisoners’ rights, digital forensics firm Arsenal Consulting found that his phone had been infected in July 2017 and April 2018. His phone number appeared in the Project Pegasus leaks.

Syed Abdul Rahman Geelani

Geelani (also known as SAR Geelani), a Delhi University professor serving time in India for ties to an outlawed Maoist group and prisoners’ rights activist, was found by Amnesty to have been infected between 2017 and 2019.

Sushant Singh

A journalist who covered defense issues for The Indian Express, and was investigating a massive deal between India and France, was found by Amnesty to have been infected as part of Project Pegasus.

S.N.M. Abdi

Journalist for India’s Outlook had his phone infected by Pegasus in April 2019, May 2019, July 2019, October 2019 and December 2019, Amnesty found as part of Project Pegasus.

Bela Bhatia

An Indian human rights lawyer whose phone was found to have been infected in 2019, and is one of five victims who are part of WhatsApp suit against NSO.

Siddharth Varadarajan

An Indian investigative journalist who is the former editor of The Hindu and founding editor of The Wire, a Pegasus Project partner. He had his phone targeted with NSO-made spyware in April 2018. Forbidden Stories and Amnesty International’s Security Lab’s forensic analysis revealed he was successfully infected.

Unnamed legal officer

The legal officer was also confirmed to have been hacked with spyware following the Project Pegasus investigation.

Ankit Grewal

The lawyer and so-called anti-caste activist was found to have been targeted in 2019 – one of a large group of victims named by WhatsApp in its suit against NSO.

Read our full story on Pegasus in India

ISRAEL

Shai Babad

A former director general of the Finance Ministry who was also a politician and also served in a senior position in Israel’s public broadcaster. Israeli business daily Calcalist said his phone had been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police. All of the Israeli cases listed below are based on Calcalist reporting that has yet to be confirmed or reviewed by Haaretz or international bodies.

Avi Berger

The former director general of the Communications Ministry and a witness in the ongoing Case 4000 trial against former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Calcalist reported that Berger’s phone had been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Aviram Elad

The former editor of Walla, which allegedly provided Netanyahu with better coverage in a quid pro quo involving its parent company, the telecom giant Bezeq, in Case 4000. Calcalist said his phone was infected by the Israel Police.

Iris Elovitch

The wife of Bezeq owner Shaul Elovitch; both are defendants in Case 4000. Her phone was infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police, Calcalist reported.

Keren Terner-Eyal

A former director general of the transportation and finance ministries, Terner-Eyal assumed the latter position after Babad left the role. Calcalist said her phone was infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Shlomo Filber

A former director general of the Communications Ministry, who was appointed by Netanyahu in 2015 and now serves as a key state’s witness in the Bezeq quid pro quo case. Filber was the first Israeli whose name was published by Calcalist as having been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Miriam Feirberg

The mayor of Netanya, who was suspected of corruption and investigated by the police until her case was closed in 2019. Calcalist said her phone had been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Stella Handler

The former CEO of Bezeq, was said by Calcalist to have been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police. Handler is part of Case 4000.

Yair Katz

The chairman of the workers union at Israel Aerospace Industries and son of former Likud lawmaker Haim Katz was said by Calcalist to have been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Rami Levy

A prominent Israeli businessman famous for his low-cost supermarket chain who also owns a small telecom firm. Calcalist reported that his phone was infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police. He was investigated by the police in the past.

Topaz Luk

A former adviser to Netanyahu who is considered close to his son, Yair Netanyahu, and served a number of roles in past campaigns. He is also credited with key aspects of the then-prime minister’s media strategy. Calcalist said Luk’s phone had been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Dudu Mizrahi

The CEO of Bezeq, who took over the telecom company after Handler. Calcalist said his device was infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Avner Netanyahu

The youngest son of former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Calcalist reported that Avner Netanyahu’s phone had been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Emi Palmor

A jurist and former director general of the Justice Ministry who currently serves on Facebook’s Advisory Board. Calcalist reported that his phone had been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Yaakov Peretz

The mayor of Kiryat Ata, who was suspected of corruption in 2019 and investigated by the police until the case was closed in 2020. Calcalist reported that his phone had been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Moti Sasson

The six-term mayor of the Tel Aviv suburb of Holon was another mayor whose phone was infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police, according to Calcalist.

Ilan Yeshua

The CEO of the news website Walla, which allegedly provided Netanyahu with better coverage in a quid pro quo involving its parent company Bezeq. Yeshua is also part of Case 4000 and was infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police. Calcalist reported.

Jonatan Urich

A former adviser to Benjamin Netanyahu and considered close to his son, Yair. He served a number of roles in various electoral campaigns and is credited with key aspects in Netanyahu’s media strategy. Urich, whose phone was hacked by Israeli police as part of an investigation, was also said by Calcalist to have been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Walla journalists

As part of Case 4000, a number of journalists with the news site were said by Calcalist to have been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police.

Protest leaders

The leaders of three protest movements were said by Calcalist to have been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police. The protest movements targeted were: Israelis with disabilities; Israelis of Ethiopian descent; and heads of the anti-Netanyahu protests. The first were fighting for better rights, the second demonstrated against police violence and the third sought to oust Netanyahu.

Extreme settlers

A number of extreme settlers were said by Calcalist to have been infected with Pegasus by the Israel Police ahead of the evacuations of illegal outposts.

Read our full story on Pegasus in Israel

JORDAN

Hala Ahed Deeb

Jordanian human rights lawyer, unionizer and feminist activist was found by Front Line Defenders to have been infected with Pegasus since March 2021.

Ahmed al-Neimat

A rights activist focused on workers rights and combating corruption. He works with a reform group called Hirak and has been targeted in the past, facing arrest for “insulting the king” and even a travel ban. Front Line Defenders and Citizen Lab found his phone was hacked at the end of January 2021, likely through the FORCEDENTRY exploit, making him the earliest victim of that particular method. His phone was likely hacked using the exploit’s zero-click capabilities.

Suhair Jaradat

A rights activist and journalist focused on women’s rights in Jordan and the Arab world who serves on the executive committee of the International Federation for Journalists. She was hacked six times between February and December 2021, through the FORCEDENTRY exploit in iPhones. The last hack took place after Apple had patched the breach, informed potential victims across the world and sued NSO. Jaradat did not update her phone and was thus still exposed.

Malik Abu Orabi

A rights lawyer who works with prominent Jordanian unions and was previously arrested by the state for his efforts. He was hacked at least 21 times between August 2019 and July 2021.

Anonymous journalist

A female journalist was also hacked, Front Line Defenders and Citizen Lab found. She requested to remain anonymous.

Read our full story on Pegasus in Jordan

KAZAKHSTAN

Aizat Abilseit, Dimash Alzhanov and Tamina Ospanova

Three members of the opposition group Wake Up, Kazakhstan whose phones were found by Amnesty’s Security Lab to have been infected by Pegasus in June 2021. Apple also warned them about the hack, which it attributed to a “state-sponsored attacker.”

Darkhan Sharipov

The Kazakh activist’s phone was also found by Amnesty to have been infected by Pegasus in June 2021.

Suspected operator: Kazakhstan

Read our full story on Pegasus in Kazakhstan

LEBANON

Lama Fakih

Human Rights Watch’s crisis and conflict director also heads the group’s Beirut office. She was targeted with Pegasus spyware at least five times between April and August 2021, HRW and Amnesty International’s Security Lab found.

Suspected operator: Unknown

MOROCCO

Hicham Mansouri

Freelance investigative journalist and co-founder of the Moroccan Association of Investigative Journalists had his iPhone infected with Pegasus more than 20 times between February and April 2021, the Project Pegasus investigation revealed. Mansouri fled Morocco in 2016 and is now based in Paris.

Mahjoub Mleiha

Human rights activist from Western Sahara who is active in the Collective of Sahrawi Human Rights Defenders, now lives in Belgium, where he is also a citizen. Amnesty found that his phone had been infected.

Joseph Breham

A French lawyer who is involved in a lawsuit against Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed over claims of torture and inhumane treatment in Yemen. Amnesty confirmed that his phone had been infected with Pegasus using the same type of messages other alleged victims in Morocco also received.

Oubi Buchraya Bachir

Sahrawi diplomat who has served as its representative in a number of African countries. Amnesty confirmed as part of Project Pegasus that his phone was infected.

Maati Monjib

Founder of the Moroccan Association for Investigative Journalism and the NGO Freedom Now (dedicated to protecting the rights of journalists and writers), Amnesty found that his phone had been infected in 2019.

Omar Radi

An independent, award-winning Moroccan journalist whose phone was found by Amnesty to have been infected in 2019.

Aboubakr Jamaï

Jamaï is a journalist who has long inspired the ire of Morocco’s royal family. Citizen Lab together with Access Now found his phone had been infected with Pegasus after materials on it were leaked online in an attempt to tarnish Jamaï and his associates.

Fouad Abdelmoumni

A Moroccan human rights and democracy activist who works with Human Rights Watch and Transparency International Morocco, Abdelmoumni’s phone was found to have been infected, most likely by the Moroccan intelligence services. Citizen Lab investigated the hacking after being commissioned by WhatsApp.

Suspected operator: Morocco

PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES (WEST BANK)

Ghassan Halaika

Human rights activist working for Al-Haq, a Palestinian NGO blacklisted by Israel, whose phone was infected in July 2020. The confirmation was made by human rights organization Front Line Defenders.

Ubai Aboudi

The phone of the director of the Bisan Center for Research and Development, a Palestinian NGO blacklisted by Israel, was infected in 2020 and confirmed by Front Line Defenders.

Salah Hammouri

Lawyer and researcher with the Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association, a Palestinian NGO blacklisted by Israel, whose phone was infected in 2020, according to Front Line Defenders.

Three unnamed activists

Phones of three activists working with Palestinian NGOs blacklisted by Israel were infected in 2020, and confirmed by Front Line Defenders.

Suspected operator in all six cases: Israel

Read our full story on Pegasus in the West Bank

POLAND

Krzysztof Brejza

Polish senator and member of the opposition party Civic Platform whose phone was confirmed to have been infected over 30 times in 2019. The confirmation was made by Citizen Lab and reported by AP.

Roman Giertych