Judicial Immunity from Civil and Criminal Liability

Jeffrey M. Shaman. * Professor of Law, DePaul University College of Law; Senior Fellow, American Judicature Society. The author appreciates the support of the DePaul University College of Law for this article and wishes to thank Professors Steven Lubet and James Alfini for their valuable comments about the article.

[VOL. 27: 1, 1990] Judicial Immunity SAN DIEGO LAW REVIEW

INTRODUCTION

It is generally thought that some of those who serve in government should possess some degree of immunity from civil liability for acts performed as part of their official duties.’ This is considered necessary so that government officials who are called upon to exercise discretion in their duties will not be deterred from vigorously performing their jobs in the public interest’ Thus, in the United States, members of the executive branch, such as governors,3 teachers, 4 police officers, 5 and prison officials,6 have been granted, under the common law, a qualified immunity from civil liability for their official actions. Under this qualified immunity, executive officers are exempt from civil liability for their wrongful behavior unless it can be shown that they knew or should have known that their behavior was improper.’

On the other hand, under the common law, legislators enjoy absotlute immunity in their official functions,8 and judges likewise enjoy absolute immunity from civil liability for their official functions so long as they are not utterly lacking in jurisdiction.” Absolute immunity for judges means that they may not be sued for their wrongful judicial behavior, even when they act for purely corrupt or malicious reasons. 10 The doctrine of judicial immunity is deeply entrenched in our legal system. It has been used to guard judges from common law causes of action, including false imprisonment,” malicious prosecution,12 and libel, 13 as well as from statutory causes of action for the deprivation of civil liberties and constitutional rights. 14 This immunity, however, does not apply to disciplinary actions against judges for violations of the professional and ethical standards that pertain to their conduct. This Article examines the doctrine of judicial immunity in the civil and criminal spheres. It analyzes the application of judicial immunity, as well as its limits, and appraises the notion that judicial immunity must be absolute to be effective.

I. HISTORY OF JUDICIAL IMMUNITY

It is often said that the doctrine of judicial immunity has ancient common law origins. While this may be true, some of the historical claims made for judicial immunity have been exaggerated. Some historians believe that under early English law, judges were generally liable for their wrongful acts, and judicial immunity was the exception and not the rule.15 Exaggeration has also occurred in respect to the history of judicial immunity in the United States. Indeed, even the Supreme Court has made some questionable assertions about the historical status of judicial immunity in this country. In a 1967 opinion, the High Court contended that the doctrine of judicial immunity had been settled and accepted throughout the states by the year 1871.18 More thorough research, however, has shown that in 1871 there was substantial variation about judicial immunity from state to state.17 In that year, thirteen states followed the rule of absolute immunity; nine states had considered the issue of immunity but had not ruled definitively on it; nine other states had not considered the issue; and six states had ruled that judges are not immune if they act maliciously.18

As a historical matter, the doctrine of judicial immunity arose in response to the creation of the right of appeal. In the tenth and eleventh centuries in England, when no right of appeal existed, losing litigants could challenge unfavorable judgments on the ground that they were false.’ 9 The litigant was entitled to both the nullification of a false judgment and a fine (known as an amercement) against the judge who had rendered it.20 As the right to appeal became available, it replaced amercements against judges, and gradually the doctrine of judicial immunity developed.” In modern times, however, it has become questionable whether the availability of appeal is in all instances an adequate substitute for imposing liability on judges for their wrongful acts. Although a judge’s act may eventually be reversed on appeal, the victim of the judge’s behavior may have suffered damage in the interim for which appeal may not compensate. Indeed, irreversible and serious damage may have occurred, which is not correctable by appeal.

Nevertheless, once appeal became available, judicial immunity was gradually accepted under the common law. In the seminal case of Floyd v. Barker,22 decided by Lord Coke in 1607, judicial immunity was established for judges who served on English courts of record. In that decision, Lord Coke discussed for the first time what are now considered some of the modern policies that underlie the doctrine of judicial immunity. Judicial immunity serves the following purposes according to Lord Coke: (1) It insures the finality of judgments; (2) it protects judicial independence; (3) it avoids continual attacks upon judges who may be sincere in their conduct; and (4) it protects the system of justice from falling into disrepute.2 Some of the purposes that have been advanced in support of judicial immunity are less convincing than others. It is debatable whether any of them justify absolute, rather than limited, immunity for judges. In a nation such as ours, which is founded on freedom of speech and which encourages criticism of government officials, using judicial immunity to protect the reputation of the judiciary is barely, if at all, legitimate. Ensuring the finality of judgments may be a valid goal, but it is not strong enough to justify absolute immunity for malicious judicial behavior that causes serious harm to others. While innocent judges should be sheltered from continual harassment, what about judges who are not innocent? Protecting judicial independence is an extremely important goal, but still, one wonders if absolute immunity is necessary to safeguard the independence of the judiciary.

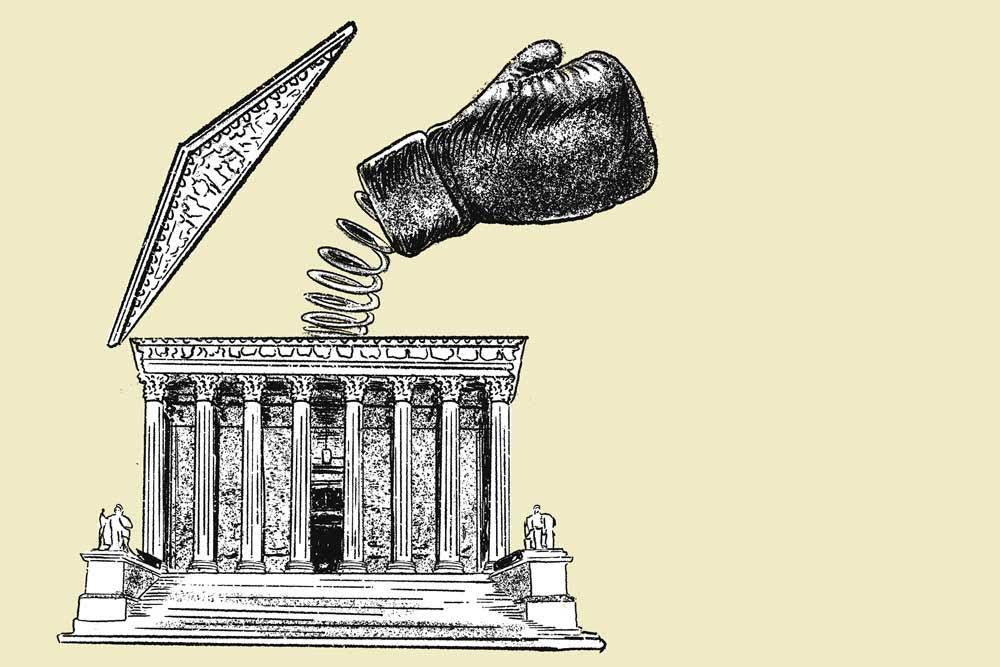

Today it is generally recognized that the most important purpose of judicial immunity is to protect judicial independence. 24 As the Supreme Court has said, judicial immunity is needed because judges, who often are called upon to decide controversial, difficult, and emotion-laden cases, should not have to fear that disgruntled litigants will hound them with litigation charging improper judicial behavior.25 To impose this burden on judges would constitute a real threat to judicial independence. The question that remains, however, is whether absolute, as distinguished from qualified, immunity is necessary to protect judicial independence. Absolute immunity is strong medicine, justified only by a grave threat to the effective administration of justice.26 As Justice Douglas suggested in his dissenting opinion in Pierson v. Ray, 7 perhaps immunity should not extend to all judges, under all circumstances, no matter how outrageous their

conduct.28

The grant of absolute immunity to judges has often been criticized, especially because it is judges who have granted absolute immunity to themselves. 29 Referring to the rule of absolute immunity for judges, an esteemed commentator once remarked that a “cynic might be forgiven for pointing out just who made this rule.”30 Moreover, the rule has been applied in some infamous cases in which judges have engaged in egregious behavior. Stump v. Sparkman,3′ a 1978 Supreme Court decision, was such a case. This case involved a state court order authorizing the sterilization of a fifteen-year-old girl on the petition of her mother. The mother’s petition stated that the girl was somewhat retarded and had begun dating men, making sterilization necessary to prevent pregnancy. However, the girl’s high school record indicated that in all probability she was not retarded.3 2 The state court judge who granted the petition ordering sterilization of the girl did not hold a hearing, appoint counsel or a guardian ad litem for the girl, or notify her of the petition or subsequent order.33 Despite these flagrant violations of due process of law, the Supreme Court ruled that the state court judge possessed absolute immunity for his acts and could not be held liable for any harm they caused. Tremendous criticism has since been directed at the Supreme Court’s decision in Stump,3 4 but absolute immunity for judges remains the rule.

II. To WHOM IMMUNITY APPLIES

As a general matter, judicial immunity protects all judges, from the lowest to the highest court, so long as they are performing a judicial act that is not clearly beyond their jurisdiction.3 5 Judicial immunity is enjoyed by both state and federal judges, 6 and by judges of general jurisdiction as well as limited jurisdiction. 37 Although, at one time, judges of inferior courts or courts of limited jurisdiction were afforded a restricted degree of immunity or no immunity at all,38 that is no longer the case. Today these judges possess the same degree of immunity as any other judges.39 Justices of the peace, magistrates, and other lay judges are included within the grant of immunity enjoyed by the judicial branch.40 However, many of the cases in which immunity has been denied because the judge acted in clear excess of jurisdiction involve justices of the peace or other lay judges.41 This suggests that in practice there may be less tolerance of judicial immunity for judges who are not formally trained in the law.42 Judicial immunity has been given to administrative law judges and hearing examiners in administrative agencies.43 It has been held that court commissioners are judicial officers and, therefore, entitled to immunity for their official acts.44 Judicial immunity also has been granted to persons who perform quasi-judicial functions, and to individuals whose authority is the functional equivalent of that exercised by a judge.4 ” But judicial immunity will not be extended to persons who are not at least quasi-judicial officers,46 nor will it be extended beyond their judicial functions.47 When judges delegate their authority or appoint persons to perform services for the court, their judicial immunity may follow the delegation or appointment. Court-appointed mediators have been given judicial immunity for performing judicial tasks.48 It also has been ruled that a doctor, appointed by a court to act as an examiner in an insanity hearing, is a quasi-judicial officer who possesses immunity from liability for any action taken in conjunction with the hearing.49 And court clerks and bailiffs have been granted immunity for their activities that are judicial in nature.50 The law clerks of judges also are entitled to share in judicial immunity.5 It has been said that while some of the tasks performed by court clerks are judicial in character, the work of judges’ law clerks is entirely So. 51 Law clerks are sounding boards for the judges who employ them and are privy to judges’ thoughts and ideas about the law and the cases over which they preside. One court has said-perhaps with some exaggeration-that law clerks are simply extensions of the judges whom they serve, and for purposes of absolute judicial immunity, judges and law clerks are as one.5 4

III. THE LIMITS OF IMMUNITY

A. Jurisdictional Limitations

Judicial immunity does not extend to the actions taken by a judge in the clear absence of jurisdiction. In determining if a judge acted in clear absence of jurisdiction, the focus is on subject matter jurisdiction rather than personal jurisdiction. At least one opinion, however, takes the position that if a court does not have personal jurisdiction, it lacks all jurisdiction and thereby forfeits judicial immunity. 6 It is frequently said that the scope of a court’s jurisdiction should be broadly construed in order to enhance the policies that underlie judicial immunity.57 The United States Supreme Court has stated that judges will not be deprived of immunity merely for acting in excess of jurisdiction; rather, they will be subject to liability only when acting in the clear absence of all jurisdiction.5 8 In a number of cases, judges have been sued for summarily holding individuals in contempt of court and ordering them incarcerated. 59 Several decisions have held that, while this may be an act in excess of jurisdiction, so long as the judge had subject matter jurisdiction over the case, it is not an act taken clearly in the absence of jurisdiction and therefore is not beyond the ambit of judicial immunity.60 In one case, it was ruled that a judge who issued a summary contempt order did not act in the clear absence of jurisdiction despite that the order was contrary to a longstanding precedent and was unconstitutional as well.6 On the other hand, judicial immunity has been denied where a judge issued an arrest warrant without a sworn complaint as required by law. Such an act has been held to be in clear excess of jurisdiction, and courts have refused to grant immunity from civil actions for malicious prosecution or abuse of process.6 2 In a similar vein, a justice of the peace was held liable for malicious prosecution for framing an affidavit to indicate that an offense had been committed within the territorial jurisdiction of his court when he knew full well that was not the case.6 3 Another justice of the peace was found to be acting completely beyond his jurisdiction when he tried a motorist under a statute that did not exist for an offense that occurred outside the jurisdiction of his court.64

B. Nonjudicial Acts

The immunity that judges possess from civil liability extends only to acts that are judicial in nature. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to define exactly what constitutes a judicial act. It is clear, though, that judicial immunity is defined as well as justified by the functions it serves, not by the office of the person to whom it attaches.65 In Stump v. Sparkman,6 the Supreme Court explained that the relevant factors to determine whether an act is judicial are the character of the act itself-that is, whether it is a function normally performed by a judge-and the expectations of the parties-that is, whether the parties believe they are dealing with a judge in his or her judicial capacity. 7 Applying these factors in Stump, the Court ruled that it was a judicial act when a judge approved a petition from a mother ordering the sterilization of her minor child even though the petition was not given a docket number, was not filed with the clerk’s office, “and was approved in an ex parte proceeding without notice to the minor, without a hearing, and without the appointment of a guardian ad litem.’ ‘ 8 Because it is not uncommon for state judges to be requested to approve petitions relating to the affairs of minors, and because the petition was presented to the judge in his official capacity, the Supreme Court concluded that the act in question was judicial in nature.” This conclusion was reached despite a stinging dissent asserting that what the judge did was in no way an act normally performed by a member of the judiciary. Judges, the dissent pointed out, “are not normally asked to approve a mother’s decision to have her child given surgical treatment generally” or, more specifically, to have her daughter sterilized. 1 Indeed, the dissent maintained that there was no reason to believe that the acts taken by the judge in Stump had ever been performed by any other judge in that state, either before or since. 2 Expanding on the factors articulated in Stump to decide if an act is judicial in nature, lower courts have focused on:

- Whether the precise act is a normal judicial function;

- Whether the events occurred in court or an adjunct area such as the judge’s chambers;

- Whether the controversy centered around a case then pending before the judge; and

- Whether the events at issue arose directly and immediately out of a confrontation with the judge in his or her official capacity.

These considerations are to be construed generously in support of judicial immunity, keeping in mind the policies that underlie it,74 and immunity may be granted even though one of the factors is not met.7 Moreover, a judge’s motivation to act against someone because of personal malice does not turn a judicial act into

a nonjudicial one.76 Findings of nonjudicial action are usually limited to either administrative acts, which are discussed below, or behavior that is highly aberrational.” In one case, a justice of the peace made an “arrest” and conducted a “trial” at a city dump. 8 Other cases involve judges who make “arrests” and conduct summary “trials. ‘7 9 Yet another case involved a judge who, in retaliation against an individual who had filed a complaint against him, misled a police officer into believing that the individual should be arrested and disallowed bond.80 For the most part, though, action taken by a judge in connection with a judicial proceeding will be considered judicial in nature and thus within the scope of judicial immunity. This includes acts taken in connection with child custody proceedings, 8’ commitment proceedings,82 probation matters,8 extradition,84 and disciplinary proceedings against attorneys.85 Administrative acts performed by a judge are not regarded as judicial in nature and, therefore, are not within the scope of judicial immunity.86 Even when essential to the functioning of a court, administrative acts performed by judges are not entitled to the cloak of immunity, because holding judges liable for such acts does not threaten judicial independence in the adjudicative process. 87 That an administrative act is performed by a judge is irrelevant for purposes of immunity; it is the nature of the act in question, not the office of the person performing it, that makes it judicial or nonjudicial.88 It should be noted, though, that the administrative chores of a judge might be within the ambit of another form of immunity, either qualified or absolute.89 In 1880, the Supreme Court held that judicial immunity did not apply to a judge charged with racial discrimination in the selection of jurors for county c6urts.90 In concluding that immunity was not available, the Court explained that whether an act done by a judge is judicial or not is determined by its character and not by the character of the agent performing it.91 The duty of selecting jurors, the Court pointed out, might just as well have been performed by a private person as by a judge.9 2 Actually, jury selection is often performed by nonjudicial personnel such as county commissioners, supervisors, or assessors, and at one time was performed by sheriffs. When done by these officials, jury selection can hardly be considered a judicial function, and the happenstance that it is performed by a judge does not change its essential nonjudicial character.9 3 At one time there was a split among the federal circuit courts of appeals whether, for purposes of determining immunity, actions taken by judges toward court employees were judicial or administrative in nature. Some circuits had ruled that judges are not immune from civil liability for demoting or firing employees for improper reasons such as racial or gender discrimination. 4 Focusing upon the nature of the judge’s action and the capacity in which a judge deals with an employee, these courts concluded that demoting or discharging an employee is an administrative act to which judicial immunity does not attach.9 5 On the other hand, in Forrester v. White,96 the Seventh Circuit

held that a judge does possess judicial immunity from liability for a claim that the judge improperly demoted and discharged a probation officer. The court took the approach that immunity attaches if a judge’s relationship with a court employee affects the judge’s capacity to perform judicial functions. In the court’s view, a judge’s relationship with a probation officer affects the judge’s ability to make decisions regarding sentencing, probation, and parole, and therefore should be protected by judicial immunity. 1 Just a few days later, though, the same court ruled that a judge did not possess immunity from liability for firing a court reporter because the relationship between a judge and court reporter does not implicate the judicial function.98

The split among the federal circuits was resolved when the United States Supreme Court reversed the Seventh Circuit’s decision in Forrester.99 The High Court explained that there is no meaningful distinction between a judge who fires a probation officer and any official of the executive branch who is responsible for employment decisions. 100 These employment actions are not part of the judicial function, regardless of who performs them. And while it is true that some personnel decisions made by judges may be crucial to the proper operation of the courts, the same is true when it comes to the operation of the other branches of government. 101 Judges, like other government officials, may enjoy a qualified immunity in their treatment of employees, but because employee relations involve administrative matters rather than judicial ones, judges are not entitled to absolute judicial immunity for their actions toward court employees. 102 According to the general rule, a prior, private agreement by a judge to rule in favor of one of the parties to a lawsuit is a judicial act within the scope of judicial immunity.103 It has even been held that where a judge conspires to rule against an individual and thereby denies the individual’s constitutional rights, such action, while clearly, improper, is nonetheless judicial in nature and therefore immune from civil liability.10 4 Thus, if a judge agrees or conspires with a prosecutor, other attorney, or a litigant, to decide a case a certain way, judicial immunity will not be forfeited. Moreover, bad faith, personal interest, or malevolence on the part of the

judge in entering a prior agreement or conspiracy will not dissipate judicial immunity. 0 5 Advance agreements or conspiracies by a judge to rule in favor of a party are within the scope of judicial immunity so long as the judge is not acting in the clear absence of jurisdiction.10 6 The courts have said that were it otherwise, judges could be hauled into court and made to defend their judicial acts on mere allegations of conspiracy or prior agreement. This is the precise harm that judicial immunity was designed to avoid.107 Nevertheless, this may be an area where judicial immunity is carried too far. After all, a prior, private agreement by a judge to rule in a particular way is totally incompatible with the judicial role of deciding cases impartially on the basis of evidence and arguments presented in court with all parties present. At one time, the Ninth Circuit recognized that prior agreements to rule a certain way were not functions normally performed by a judge, and therefore should not be considered judicial acts within the ambit of judicial immunity.108 However, the Ninth Circuit later reversed itself by focusing on the judge’s act of ruling in a case, which is judicial in nature, rather than focusing on the prior agreement to rule, which is not.109

This reversal aligned the Ninth Circuit with the other federal circuits that consistently take the position that prior agreements are judicial in nature and therefore immunized from liability.”10 This position extends judicial immunity to its breaking point. It is no less logical to focus on the prior agreement to rule than it is to focus on the act of ruling, and it is difficult to accept the assertion made by the courts that the purposes of judicial immunity require a scope so broad as to include prior agreements and conspiracies.”‘ Certainly, a cynic would wonder whether anyone but a judge would extend judicial immunity so far.

C. Injunctive Relief and Attorney’s Fees

Under the common law, injunctive relief against judges was unknown.” 112 Injunctive relief was an equitable remedy available only from the chancellor against parties to cases being heard in other courts.”113 As the Supreme Court has observed, this restriction upon the use of injunctions indicates nothing about the proper scope of judicial immunity because the restriction derived from the substantive limits of the chancellor’s authority and not from the dictates of judicial immunity.114 Moreover, even under the common law, collateral relief against judges was available in the form of various writs, such as mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto, and habeas corpus.115 Thus the common law provided for relief, analogous to injunctive relief, against judges even when alternative avenues of review existed.’1 0 This has led the Supreme Court to conclude that in the common law, there was no inconsistency between the principle of judicial immunity and the availability of collateral injunctive relief against judges in exceptional circumstances. 117 There has been general agreement that the doctrine of judicial immunity does not bar injunctive relief against judges.”118 There are several reasons for this. The first is that injunctions, being a form of equitable relief, may only be granted upon a showing that the plaintiff is suffering irreparable injury for which there is no adequate legal remedy.” 119 This requirement substantially diminishes the charge that judicial independence will be threatened by disgruntled litigants seeking injunctive relief against judges.’ 20 Second, an injunction directing a judge to do or to refrain from doing something within the judge’s official capacity does not subject the judge to personal liability and, hence, does not threaten a judge in the same way as an action for damages which the judge may have to pay out of personal funds. Injunctive relief, then, does not pose the same kind of risk to the judiciary as other forms of liability, and therefore, it is not necessary to use judicial immunity to interdict it. Judicial immunity is a creation of the common law and, like any other common law construct, can be superseded by statute. This principle was recognized by the Supreme Court in Pulliam v. Allen,12 1 in which the Court held that Congress may authorize the awarding of attorney’s fees against judges, even when money damages would be precluded by the doctrine of judicial immunity. Pulliam arose from a civil rights action filed against a state magistrate who repeatedly incarcerated criminal defendants for nonjailable offenses when they were unable to post bond. The federal district court in which the case was filed found this practice to violate due process and equal protection of law, and issued an injunction to prohibit it.

The district court also found that the plaintiffs were entitled to attorney’s fees in the amount of $7038. The attorney’s fees were awarded by the court under the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976,122 a federal statute that authorizes courts to award attorney’s fees to plaintiffs whose constitutional rights have been violated.

On appeal to the Supreme Court, the defendant-magistrate argued that the award of attorney’s fees should be barred by judicial immunity because attorney’s fees are the functional equivalent of monetary damages, the award of which are precluded by immunity. 23 While agreeing that there was some logic to the defendant’s argument, the Court nevertheless upheld the award of attorney’s fees on the ground that it was for Congress, not the Supreme Court, to determine whether and to what degree to abrogate the common law doctrine of judicial immunity. 2 4 The Court stated that the legislative history of the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Award Act of 1976 made it perfectly clear that Congress intended that judicial immunity should not be a bar to an award of attorney’s fees, even when damages would be precluded by judicial immunity.12 5

IV. IMMUNITY FROM CIVIL LIABILITY FOR DEFAMATION

On occasion, judges are sued for making remarks or written statements that are allegedly defamatory. The rule of absolute judicial immunity shields judges from civil liability for any defamatory remarks or statements that they may make. 26 Judicial immunity from making a defamatory utterance or statement is, of course, an incident of the civil immunity that judges possess in general. It therefore serves all of the (previously discussed) purposes of judicial immunity, the most important of which is to protect the independence of the judiciary. 127 A few courts have taken the position that a judge is immune from liability for defamation only for statements that bear relevance to proceedings before the judge.12 8 This position, however, apparently confuses the doctrine of judicial immunity with another doctrine by which statements made by any participant in a judicial proceeding are privileged. 129 Under the latter doctrine, which functions to foster

openness in the judicial process, defamatory statements made by a witness, party, or attorney to a lawsuit are privileged (and hence, cannot form a basis for liability) so long as they are made in the course of a judicial proceeding and are relevant to it. 130 On the other hand, judicial immunity, even for defamation, is not conditioned upon a requirement of relevancy, and the majority of courts have so held.” Otherwise, the goals served by judicial immunity, especially the protection of judicial independence, would be hampered. As with other instances of judicial immunity, a judge accused of defamation will not be granted immunity when the judge was acting in the clear absence of jurisdiction13 2 or when the judge was acting in a nonjudicial capacity. 133 In accordance with the latter rule, judicial immunity only extends to defamatory statements made in the course of performance of a judicial function.”3 Even if made in the courtroom, defamatory statements made beyond the scope of the judicial role are not covered by immunity. 13 On the other hand, statements made by a judge outside the courtroom (as well as those made in it) are immune if made as part of the judicial function. 36 It is not always a simple matter to determine the perimeters of a judge’s duties and whether a defamatory statement has occurred within or beyond them. That a lawsuit has been finally concluded does not necessarily signal the end of the judicial role in it. Thus, in one case, it was held that immunity still existed in regard to a letter written by a judge to a prison warden, providing information for future parole hearings concerning a criminal defendant already sentenced by the judge. 37

When judges are required by law to convey their opinions to a court reporter for publication, this is clearly part of the judicial function, and therefore, any defamatory remarks contained in their published opinions are absolutely immune. 38 However, a New York court held that it was not part of a judge’s function to send opinion to an unofficial reporter, and therefore, defamatory statements in the opinion were not cloaked with immunity. 3 9 Distinguishing between official and unofficial reporters seems highly questionable, and in a subsequent New York case, a circuit court reached a contrary result.140 Even in New York, it is clear that when a judge is directed by law to submit an opinion to.a reporter, statements in the opinion are covered by judicial immunity. If a judge did not play a part in sending the opinion to the reporter, the judge cannot be held liable for any defamatory remarks it may contain.1 41

V. MISAPPROPRIATION OR MISUSE OF FUNDS AND ESTATES

There are cases in which judges have been found civilly liable for misappropriating funds entrusted to their care.14 However, in these cases the doctrine of judicial immunity apparently was overlooked, because there is no mention of it. Nevertheless, misappropriation of funds entrusted to the care of a judge may be beyond the scope of immunity on the ground that it is not a judicial act. Or, liability for misappropriating funds may be imposed on judges by statutory provisions that overrule, in some aspects, the common law doctrine of immunity. 43 Whatever the rationale might be, it seems quite reasonable to hold judges liable for misappropriating funds for their own use. Such behavior, after all, amounts to theft, and judges should be made to return any funds they have stolen from others.

On the other hand, immunity should shield judges from liability for honest errors of judgment they may commit in administering funds or estates assigned to their care. According to the case law, judges do possess immunity for honest mistakes in the administration of funds or estates.144 There are a few decisions, though, which state that immunity does not cover ministerial acts by judges that result in negligent loss to an estate.’ 45 Ministerial acts are usually regarded as nonjudicial in character and, hence, not within the ambit of immunity.146 In some instances, judges are made liable by statute for the negligent administration of an estate resulting in loss to the estate.147

VI. JUDICIAL IMMUNITY FROM CRIMINAL LIABILITY

A. General Rule of No Immunity

But for one narrow exception, 45 judicial immunity does not exempt judges from criminal liability.’49 Courts have stated unequivocally that the judicial title does not render its holder immune from responsibility even when the criminal act is committed behind the shield of judicial office. 150 As is the case regarding immunity from civil liability,’ immunity from criminal liability does not extend to nonjudicial acts or acts taken in the clear absence of all jurisdiction. 5 2 Even beyond such acts, however, judicial immunity generally is not available for criminal behavior. For instance, judicial immunity does not shield judges from criminal liability for fraud or corruption, or for soliciting or accepting bribes.’5 3 This is as it should be; although important, the purposes of the doctrine of judicial immunity are not so important that they transcend the function of the criminal law to protect the public from crime, especially crime as egregious as fraud, corruption, or bribery. As a consequence, judicial immunity normally stops short of protecting criminal behavior.

The one area where judges can be said to enjoy immunity from criminal liability is for malfeasance or misfeasance in the performance of judicial tasks undertaken in good faith.’ In some states malfeasance or misfeasance in office is made criminal either by statute or common law rule. 15 5 However, this criminal liability will be

precluded by judicial immunity unless the malfeasance or misfeasance is accompanied by bad faith. 56 Furthermore, even in this area, judicial immunity will not be granted for malfeasance or misfeasance by a judicial officer in the performance of an act that is administrative in character rather than judicial. In Ex parte Virginia,157 the Supreme Court ruled that judi- cial immunity would not be given to a judge indicted for excluding qualified black persons from jury lists because the selection of jurors was an administrative task, not a judicial one.’58 As previously noted, the nonjudicial nature of jury selection is indicated in that it is a task often performed by nonjudicial personnel and, indeed, is one that could be performed by private persons.’59 Given the ministerial character of jury selection, the court ruled, the judge was not protected by judicial immunity from criminal liability. 60 The Supreme Court’s decision in Ex parte Virginia apparently was overlooked in Commonwealth v. Tartar,’6 ‘ in which the Kentucky Court of Appeals ruled that a judge was entitled to immunity from criminal misfeasance for improperly certifying a list of grand jurors whose names had not been drawn from a jury wheel or drum as required by law. Although the judge’s action in this case would seem to be no less a ministerial task than the judge’s action in Ex parte Virginia, the Tartar court made no mention of the thought that certification of jurors might be a nonjudicial task not covered by immunity. While the situation in Tartar, unlike that in Ex parte Virginia, did not involve the pernicious behavior of racial discrimination, the supposedly controlling factor in granting immunity is whether the act in question is judicial or administrative; in that respect, the cases appear to be indistinguishable.

Except for cases involving malfeasance or misfeasance in office, claims of judicial immunity for criminal behavior are unavailing. Hence, in Braatelien v. United States,1 2 it was held that a judge could not claim immunity from a criminal charge of conspiring to defraud the government. The court pointed out that the judge in question had not been indicted for an erroneous or even wrongful judicial act, but for criminal behavior that was distinct from his official functions. 163 The court noted that the crime could have been completed without the performance of a single judicial act by the judge and, therefore, amounted to nonjudicial behavior beyond the bounds of immunity. 64 Moreover, the court stated that judges may be held criminally responsible for fraud or corruption because judicial immunity provides no cloak for criminal behavior.,,

Immunity from criminal liability was also found not to exist in McFarland v. State, 66 in which a judge not only collaborated with a criminal defendant to wrongfully secure the defendant’s release by issuing a void writ of habeas corpus, but also improperly cited another judge for disregarding the void writ. For engaging in these actions, the judge was charged with the crime of constructive contempt, and on appeal to the Supreme Court of Nebraska it was ruled that the judge could not claim immunity for this sort of behavior because it was nonjudicial in nature. Indeed, the Nebraska high court made the statement that “[t]o say that such conduct was outside the realm of judicial action is to put it mildly.””6 7 This statement, though, is questionable. Although the court undoubtedly was correct in saying that the judge acted fraudulently and corruptly, and that he unlawfully attempted to interfere with a criminal proceeding, the fact remains that the judge did so, at least in part, by issuing a writ and a contempt citation-both of which are actions that judges normally perform, and that would usually be considered judicial functions. However, the court was on more solid ground in noting that the judge acted in the absence of jurisdiction, and that judicial immunity does not extend to this sort of criminal behavior.” 8

Judges need not be impeached before being indicted and tried on criminal charges.’69 Even federal judges, who “hold their Offices during good Behavior”‘ 170 under article III of the Constitution, may be criminally prosecuted while still in office. The Constitution does not bar the trial of a judge for alleged crimes committed before or after taking office. The tenure granted to federal judges by article III is not meant to give shelter to criminal behavior, and therefore, impeachment of a judge is not a prerequisite to criminal prosecution.’17

B. Criminal Activity as Grounds for Removal from Judicial

Office or Other Disciplinary Sanctions

In some states it is provided by constitutional enactment, statute, or supreme court rule that conviction of a judge of certain crimes operates to automatically remove the judge from office. The content of these provisions differ slightly: most mandate removal from office upon conviction of a felony, 172 others upon conviction of a crime involving moral turpitude,172 and yet others upon conviction of an “infamous” crime.1 4 Essentially, they all provide for removal from office of judges who have been convicted of committing a serious crime. Under these provisions, judges have been removed from office for engaging in mail fraud,175 racketeering,’ 76 bribery,177 extortion, 7 8 obstructing justice, 17 9 assault, 80 and other felonies or serious crimes.’ 8′ These provisions ordinarily do not allow judges to challenge their convictions as being erroneous; once a conviction becomes final, that in itself will operate to require a forfeiture of the judicial office’8 2 and may also disqualify the convicted judge from holding office in the future.’ 83 Some provisions further direct that if a judge is indicted on a serious criminal charge, the judge will be suspended from office, pending final adjudication of the charge.184 It has been held that such suspensions, even though they occur prior to a determination of guilt, do

not violate the due process clause because of the overriding public interest in ensuring an upstanding judiciary.8 5 During the period of suspension, a judge may continue to be entitled to receive his or her salary.’8 6 But once a criminal conviction becomes final, permanent forfeiture of office will occur and the payment of salary will be terminated.18 7 Criminal behavior on the part of a judge also may run afoul of the Code of Judicial Conduct. Criminal conduct is an affront to canon 1 of the Code, which requires judges to uphold the integrity of the judiciary and to observe high standards of behavior. 188 Criminal conduct further offends canon 2, which requires judges to avoid impropriety and the appearance of impropriety in all of their activities. 18 9 Indeed, criminal activity obviously contravenes both of these canons by undermining public confidence in the judiciary and impairing the administration of justice. 90

A wide variety of crimes have been held to violate the Code of Judicial Conduct when committed by a judge. They include tax evasion, 191 receiving stolen goods, 92 contributing to the delinquency of a minor, 193 driving under the influence of alcohol,9 use of illegal drugs, 95 jury tampering, 98 racketeering, 0 7 battery,’9 8 resisting police officers,’ 99 and welfare fraud.200 These are but some of the criminal actions that have been found to violate the Code of Judicial Conduct.

Some courts have held that even in the absence of a criminal conviction, a judge may violate the Code of Judicial Conduct if it merely appears that the judge has committed a crime. This occurred in In re Killam,2 ° ‘ in which a judge was charged with driving under the influence of alcohol. At his criminal trial, the judge admitted facts sufficient to establish a finding of guilt on the charge, but the trial court continued the case for one year on the condition that the judge enter and successfully complete a driver alcohol education program. The judge did so, and the criminal charges against him eventually were dismissed. Nonetheless, in a separate disciplinary proceeding, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that the judge had violated the Code of Judicial Conduct by driving under the influence of alcohol. The dismissal of the criminal charges, in the court’s opinion, had no effect upon the disciplinary proceedings because the criminal law serves different purposes than the disciplinary process.202 Regardless of what the criminal court ruled, the state supreme court, when later considering the disciplinary action, thought the evidence disclosed in the criminal proceeding showed that the judge did actually drive while under the influence of alcohol and

thus violated the Code by bringing undeserved discredit to the judiciary.20 A plea of nolo contendere to a criminal charge, in itself, may constitute a violation of the Code. In In re Inquiry Concerning A Judge No. 491,204 the Supreme Court of Georgia upheld the Judicial Qualification Commission’s finding that a judge’s plea of nolo contendere to a crime involving moral turpitude had brought the judicial office into disrepute, in violation of the Code of Judicial Conduct, even though the question of guilt was not formally adjudicated by such a plea.20 5 Notwithstanding that there existed a statute prohibiting the use of the plea as an admission of guilt, the Georgia Supreme Court held that because the Commission was not inquiring into the guilt of the judge as charged, but merely whether the judge’s plea of no contest had brought the judicial office into disrepute, the Commission could not be restricted by legislative act from considering “any conduct of a judicial officer which reflects on the question they are called upon to decide. 206

C. The Relationship Between the Criminal Process and the Disciplinary Process: The Doctrine of Double Jeopardy

As a general rule, the doctrine of double jeopardy does not operate as a bar to judicial disciplinary proceedings regarding conduct that has previously been the subject of adjudication in a criminal trial.207

Double jeopardy ordinarily applies only when one criminal action is followed by another, and because judicial disciplinary proceedings are considered noncriminal in nature, double jeopardy does not attach between them and a prior criminal adjudication. 208 While sharing some similarities with the criminal process, judicial disciplinary proceedings are usually considered a distinct entity, sui generis, and therefore double jeopardy does not arise between the criminal and disciplinary processes.209 For purposes of the doctrine of double jeopardy, many courts consider judicial disciplinary proceedings to be noncriminal in nature because they function differently than the criminal law. 210 While some courts have arrived at this conclusion because judicial proceedings do not result in the imposition of imprisonment or fines,211 other courts have determined that such proceedings are noncriminal because their purpose is not to punish, but to maintain the honor and

integrity of the judiciary and to restore and reaffirm the public confidence in the administration of justice.2 12 In short, it has been said that the essence of the sanction imposed in disciplinary cases is not “punishment.” Instead, sanctions are based on grounds bearing a rational relationship to the interests of the state in the fitness of its judicial personnel. 213 The judicial disciplinary process further differs from the criminal process in that it does not entail severe penalties, such as imprisonment, which require special procedural protection before they may be imposed. As a result, in those instances for which the particular conduct transgresses both the criminal law and the canons of ethics, prosecution may be pursued under either or both systems without invoking constitutional double jeopardy concerns.214

Judicial disciplinary proceedings have also been described by some courts as regulatory in nature.215 In states that have adopted the two-tier model of judicial conduct organizations, 16 proceedings in the first tier, where no adjudication occurs, have been said to be merely investigatory or quasi-administrative. As such, they serve a function similar to that of a grand jury to which double jeopardy does not attach.217 (This, however, does not explain why double jeopardy concerns would not come into play at the second tier of the proceedings.)

In accordance with these general principles, the Alabama Court of the Judiciary in In re Burns,21a ruled that it was not precluded from censuring a judge for proposing an act of prostitution to a woman, in violation of’ canon 2, even though this conduct had already been the basis of the judge’s criminal conviction of disorderly conduct. Prior adjudication of the conduct in a criminal proceeding did not bar further inquiry of the same conduct in a disciplinary proceeding by the Court of the Judiciary.

The unavailability of the defense of double jeopardy to a judicial disciplinary commission proceeding is further illustrated by In re Bates.219 In Bates, the Judicial Qualification Commission of Texas was allowed to proceed with its hearing prior to the completion of criminal prosecution on the same subject matter because the Commission’s hearing was deemed a “separate and distinct matter and completely independent of any other proceedings which were pending.”‘ 220 A similar result was reached by the California Supreme Court in McComb v. Commission on Judicial Qualifications.2’ There, the court likened a judicial proceeding to that of a state bar disciplinary proceeding for which criminal procedural safeguards do not apply due to the noncriminal nature of the proceeding.222

Employing similar reasoning, courts have also held that legislative action to remove or impeach a judge on grounds of- misconduct in office does not invoke double jeopardy protection against subsequent disciplinary proceedings based on the same misconduct. In Ransford v. Graham,223 the Supreme Court of Michigan held that the refusal of the state House of Representatives to vote for the removal of a judge did not bar, on double jeopardy grounds, subsequent proceedings by the state supreme court regarding the judge’s fitness to serve.

The court held that neither the impeachment nor the disciplinary actions were criminal in nature, and therefore, the doctrine of double jeopardy did not apply.224 Likewise, the New Jersey Supreme Court has taken the position, in In re Mattera,225 that impeachment only determines a judge’s right to hold office and is not intended to bar or delay other actions for a public wrong. The court held that a single act of misconduct may offend the public interest in a number of areas, and justice requires an appropriate remedy for each harm created.226

The New Jersey Supreme Court could find no reason why a prescription in the Constitution of a remedy for one purpose should be found to imply an intention to deny government the power to protect the public in its other interests or to immunize the offender from further consequences of his or her acts.227 This view was reiterated by the Texas Supreme Court in In re Carrillo,228 where it was held that a judge’s removal from office by a state senate impeachment proceeding did not preclude judicial action based on the same conduct leading to the removal. The court ruled that both proceedings could be pursued concurrently.229

As a result of courts’ refusal to apply the doctrine of double jeopardy to judicial disciplinary proceedings, a judge’s prior criminal conviction may be admitted as evidence of judicial misconduct in a subsequent disciplinary inquiry. 3° In Louisiana State Bar Ass’n. v.Funderburk,231 a judge’s guilty plea to criminal charges was entered as competent evidence of misconduct at a subsequent commission investigation, and it created a rebuttable presumption of guilt which the respondent judge had the burden to overcome. Similarly, in In re Biggins,2 the Arizona Supreme Court held that a judge’s conviction of driving under the influence of alcohol afforded an “entirely independent and self-sufficient basis for sustaining the commission’s censure recommendation. 233 In the opinion of the Arizona court, the judge’s conviction was of sufficient consequence to be, in and of itself, conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice, bringing the judicial office into disrepute.” 4 This view was also expressed in In re Callanan,3 5 in which the Michigan Supreme Court held that a judge’s felony conviction for violations of the RICO act was sufficient evidence of conduct which brought the judicial office into disrepute. 36 The general refusal by the courts to apply double jeopardy protection to judicial disciplinary proceedings has not gone entirely without criticism. In In re Friess,237 a New York trial court said that the contention of the State Commission on Judicial Conduct that its proceedings were merely disciplinary and, therefore, not subject to criminal trial standards, was “either niave [sic] or hyprocritical [sic] “238

Whatever label might be assigned to the proceedings, the court said, was merely an exercise in semantics. The court, instead, held that common law safeguards attach “to any significant hearing where the State attempts to deprive an individual of property without due process.” 239 Viewing the current livelihood and good reputation of its judges as valuable property rights, the New York court held that a judge is entitled to all the constitutional rights of a fair trial, including, but not limited to, protection from double jeopardy or star chamber proceedings.24 Despite the concerns of the trial court in Friess, its grant of the petitioner’s request for a severance of charges in accordance with constitutional safeguards was modified by the New York appellate division in In re Application of Friess,241 to the extent of denying the request for severance and removing constitutional double jeopardy protection from disciplinary proceedings. In doing so, the appellate court distinguished disciplinary proceedings from criminal ones by their differing purposes and nature, as well as the disparity of penalties involved, noting particularly that in disciplinary proceedings the fundamental right of liberty is not at stake.242 The appellate court in Friess also pointed out that the hearer of fact in a disciplinary proceeding is routinely a seasoned former jurist as opposed to a panel of lay jurors. In the opinion of the court, these former jurists are fully capable of distinguishing between proof submitted on one charge and proof submitted on another or previous charge.243

CONCLUSION

Under the law, judicial liability for criminal activity is treated quite differently than judicial liability for tortious or other noncriminal wrongful conduct. With one minor exception for malfeasance or misfeasance in office, judges possess no immunity for their criminal behavior. Whatever threat criminal liability might pose to judicial independence, it is not strong enough to override the importance of enforcing the criminal law, even against judges. No one ought to be exempt from the criminal law, and it has been consistently recognized that judges should not be able to hide behind their office as shelter for criminal behavior that harms society.

On the other hand, judges enjoy a substantial degree of immunity from civil liability. Indeed, judges possess not only a qualified immunity from civil liability, like their fellow public servants in the executive branch, but also an absolute immunity that protects them even when they commit wrongs intentionally or maliciously. It is true that judicial immunity stops short of shielding nonjudicial actions or actions taken in the clear absence 6f all jurisdiction, but these limits on the doctrine of judicial immunity are applied sparingly, if not reluctantly. Within these limits, the intentional and malicious civil wrongs of judges, no matter how egregious, are cloaked with absolute immunity.

It is said that this grant of absolute immunity for judges is necessary to maintain judicial independence and to protect judges from harassment by disgruntled litigants. Surely these are admirable goals, but whether absolute immunity, as distinct from qualified immunity, is truly necessary to effectuate them is an open question. A grant of immunity for intentional and malicious civil wrongs has not been found necessary in the executive branch of government. Judicial independence should be scrupulously guarded and some degree of immunity from civil liability must be maintained for judges. But absolute judicial immunity from civil liability remains a debatable practice.

1. See Jaffe, Suits Against Government and Officers: Damage Actions, 77 HARV. L. REv. 209 (1963); McCormack & Kirkpatrick, Immunities of State Officials Under Section 1983, 8 RUT.-CAM. L.J. 65 (1976).

2. See Jaffe, supra note 1; McCormack & Kirkpatrick, supra note 1.

3. Butz v. Economou, 438 U.S. 478 (1978).

4. Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974).

5. Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S. 308 (1975).

6. O’Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563 (1975).

7. Butz v. Economou, 438 U.S. 478 (1978).

8. Tenney v. Brandhove, 341 U.S. 367 (1951).

9. See Stump v. Sparkman, 435 U.S. 349 (1978); Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967).

10. See Pierson, 386 U.S. at 554; Stump, 435 U.S. at 356.

11. Ravenscroft v. Casey, 139 F.2d 776 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 323 U.S. 745 (1944); Stahl v. Currey, 135 Ohio St. 253, 20 N.E.2d 529 (1939). 12. O’Bryan v. Chandler, 352 F.2d 987 (10th Cir. 1965), cert. denied, 384 U.S. 926 (1966).

13. Garfield v. Palmieri, 297 F.2d 526 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 369 U.S. 871 (1962).

14. Pierson, 386 U.S. at 555; Stump, 435 U.S. at 359.

15. Compare Feinman & Cohen, Suing Judges: History and Theory, 31 S.C.L. REv. 201 (1980) with Block, Stump v. Sparkman and the History of Judicial Immunity, 1980 DUKE L.J. 879.

16. See Pierson, 386 U.S. at 560.

17. See Note, Liability of Judicial Officers Under Section 1983, 79 YALE L.J. 322 (1969).

18. Id. at 326-27.

19. See M. COMISKY & P. PATTERSON, THE JUDICIARY-SELECTION, COMPENSATION, ETmICS, AND DISCIPLINE 233 (1987).

20. Id.

21. Id.

22. 77 Eng. Rep. 1305 (Star Chamber 1607).

23. Id. at 1307.

24. See C. WOLRAM, MODERN LEGAL ETHICs 970 (1986).

25. See Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547, 554 (1967); see also Forrester v. White, 484 U.S. 219, 226-28 (1988).

26. See Forrester v. White, 792 F.2d 647, 660 (7th Cir. 1986) (Posner, J., dissenting), rev’d, 484 U.S. 219 (1988).

27. 386 U.S. 547 (1967).

28. See id. at 558-59 (Douglas, J., dissenting).

29. Compare Note, supra note 17 with Kates, Immunity of State Judges Under the Federal Civil Rights Acts: Pierson v. Ray Reconsidered, 65 Nw. U.L. REv. 615 (1970). See also Laycock, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, 54 CHI.-KENT L. REv. 390 (1977); Nagel, Judicial Immunity and Sovereignty, 6 HASTINGS CoNsr. L.Q. (1978); Feinman & Cohen, supra note 15; Block, supra note 15.

30. W. PROSSER, TORTS 987 (4th Ed. 1971).

31. 435 U.S. 349 (1978).

32. See id. at 351.

33. Id. at 360.

34. See Nagel, supra note 29; Nahmod, Persons Who Are Not “Persons”: Absolute Individual Immunity Under Section 1983, 28 DEPAUL L. REv. 1 (1978); Rosenberg, Stump v. Sparkman: The Doctrine of Judicial Immunity, 64 VA. L. REV. 833 (1978); Feinman & Cohen, supra note 15; Block, supra note 15.

35. See Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547, 547 (1967); see also Pomeranz v. Class, 82 Colo. 173, 257 P. 1086 (1927); State ex rel. Clark v. Libbert, 96 Ind. App. 84, 177 N.E. 873 (1931); Allard v. Estes, 292 Mass. 187, 197 N.E. 884 (1935); Health v. Cornelius, 511 S.W.2d 683 (Tenn. 1974).

36. See Turner v. American Bar Ass’n, 407 F. Supp. 451 (N.D. Tex. 1975), aff’d sub nom. Taylor v. Montgomery, 539 F.2d 715 (7th Cir. 1976); Brown v. Dunne, 409 F.2d 341 (7th Cir. 1969).

37. Alzua v. Johnson, 231 U.S. 106 (1913); Sarchet v. Phillips, 102 Colo. 318, 78 P.2d 1096 (1938); Calhoun v. Little, 106 Ga. 336, 32 S.E. 86 (1898); Berry v. Smith, 148 Va. 424, 139 S.E. 252 (1927).

38. See Voll v. Steele, 141 Ohio St. 293, 47 N.E.2d 991 (1943); Williamson v. Lacy, 86 Me. 98, 29 A. 943 (1893); Robertson v. Parker, 99 Wis. 652, 75 N.W. 423(1898).

39. See Alzua, 231 U.S. at 111.

40. See Perez v. Borchers, 567 F.2d 285 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 439 U.S. 831 (1978).

41. C. WOLFRAM, supra note 24, at 971.

42. See id.

43. Butz v. Economou, 438 U.S. 478, 478 (1978).

44. Linder v. Foster, 209 Minn. 43, 295 N.W. 299 (1940).

45. Morales v. Vegas, 483 F. Supp. 1057 (D.P.R. 1979); Miller v. Reddin, 293 F. Supp. 216 (C.D. Cal. 1968).

46. See Brown v. Rosenbloom, 34 Colo. App. 109, 524 P.2d 626 (1974), afJd,188 Colo. 83, 532 P.2d 948 (1975).

47. McGhee v. Moyer, 60 F.R.D. 578 (W.D. Va. 1973).

48. Mills v. Killebrew, 765 F.2d 69 (6th Cir. 1985).

49. See Linder v. Foster, 209 Minn. 43, 43, 295 N.W. 299, 299 (1940).

50. Scott v. Dixon, 720 F.2d 1542 (11th Cir. 1983), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 832 (1984); Tarter v. Hury, 646 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1981); Slotnick v. Stavinskey, 560 F.2d 31 (1st Cir. 1977), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 1077 (1978); Adkins v. Clark County, 105 Wash. 2d 675, 717 P.2d 275 (1986).

51. Oliva v. Heller, 670 F. Supp. 523 (S.D.N.Y. 1987), a~fd, 839 F.2d 37 (2d Cir. 1988); see also Eades v. Sterlinski, 810 F.2d 723 (7th Cir.), cert. denied, 484 U.S. 847 (1987); Gray v. Bell, 712 F.2d 490 (9th Cir. 1983), cert. denied, 465 U.S. 1100 (1984).

52. Oliva, 670 F. Supp. at 526.

53. Id.

54. Id.

55. See Ashelman v. Pope, 793 F.2d 1072 (9th Cir. 1986) (en banc); Green v. Maraio, 722 F.2d 1013 (2nd Cir. 1983).

56. See Rankin v. Howard, 633 F.2d 844, 848-49 (9th Cir. 1980), cert. denied, 451 U.S. 939 (1981).

57. See Ashelman, 793 F.2d at 1076; Holloway v. Walker, 765 F.2d 517 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 474 U.S. 1037 (1985).

58. See Stump v. Sparkman, 435 U.S. 349, 356-57 (1978).

59. See King v. Love, 766 F.2d 962 (6th Cir.), cert. denied, 474 U.S. 971 (1985); see also Adams v. McIlhany, 764 F.2d 294 (5th Cir. 1985), cert. denied, 474 U.S. 1101 (1986).

60. E.g., Adams, 764 F.2d at 298.

61. Id. at 294.

62. See, e.g., Hoppe v. Klapperich, 224 Minn. 224, 28 N.W.2d 780 (1947); Utley v. City of Independence, 240 Or. 384, 402 P.2d 91 (1965).

63. State ex rel. Little v. United States Fidelity & Guar. Co., 217 Miss. 576, 64 So. 2d 697 (1953).

64. Vickrey v. Dunivan, 59 N.M. 90, 279 P.2d 853 (1955).

65. See Forrester v. White, 484 U.S. 219, 227-29 (1988).

66. 435 U.S. 349 (1978); see also supra notes 31-34 and accompanying text.

67. Stump, 435 U.S. at 362.

68. See id. at 360-62.

69. Id. at 362-63.

70. Id. at 365-67 (Stuart, J., dissenting).

71. Id. at 365-66.

72. Id. at 367.

73. See Ashelman v. Pope, 793 F.2d 1072, 1075-76 (9th Cir. 1986) (en banc); see also Dykes v. Hosemann, 776 F.2d 942 (11th Cir. 1985), cert. denied, 479 U.S. 983 (1986); Adams v. McIlhany, 764 F.2d 294, 297 (5th Cir. 1985) (citing McAlester v. Brown, 469 F.2d 1280, 1282 (5th Cir. 1972)), cert. denied, 474 U.S. 1101 (1986); Merckle v. Harper, 638 F.2d 848, 858 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 454 U.S. 816 (1981).

74. See Ashelman, 793 F.2d at 1076.

75. See Adams, 764 F.2d at 297-99.

76. Id.

77. See Gregory v. Thompson, 500 F.2d 59 (9th Cir. 1982).

78. Brewer v. Blackwell, 692 F.2d 387 (5th Cir. 1982).

79. See Harris v. Harvey, 605 F.2d 330 (7th Cir. 1979), cert. denied, 445 U.S. 938 (1980); Zarcone v. Perry, 572 F.2d 52 (2d Cir. 1978); Wall v. Heath, 622 F. Supp. 105 (S.D. Miss. 1985).

80. King v. Love, 766 F.2d 962 (6th Cir.), cert. denied, 474 U.S. 971 (1985).

81. Dear v. Locke, 128 Ill. App. 2d 356, 262 N.E.2d 27 (1970).

82. Devault v. Truman, 354 Mo. 1193, 194 S.W.2d 29 (1946).

83. Grove v. Rizzolo, 441 F.2d 1153 (3d Cir.), cert. denied, 404 U.S. 945 (1971).

84. Collins v. Moore, 441 F.2d 550 (5th Cir. 1971).

85. Peterson v. Knutson, 305 Minn. 53, 233 N.W.2d 716 (1975).

86. Forrester v. White,, 484 U.S. 219 (1988); Supreme Court of Va. v. Consum- ers Union of United States, Inc., 446 U.S. 719 (1980); Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880).

87. See Forrester, 484 U.S. at 228-30.

88. Id.

89. See Consumers Union, 446 U.S. at 731-34.

90. See Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880); see also Forrester, 484 U.S. at 228 (“Although [Ex parte Virginia] involved a criminal charge against a judge, the reach of the Court’s analysis was not in any obvious way confined by that circumstance.”).

91. Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. at 348.

92. Id.

93. Id.

94. See Guerico v. Brody, 814 F.2d 1115 (6th Cir. 1987), cert. denied, 484 U.S. 1025 (1988); Goodwin v. Circuit Court, 729 F.2d 541 (8th Cir.), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 828 (1984), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 1216 (1985); see also McDonald v. Krajewski, 649 F. Supp. 370 (N.D. Ind. 1986).

95. See cases cited supra note 94.

96. 792 F.2d 647 (7th Cir. 1986), rev’d, 484 U.S. 219 (1988).

97. Forrester, 792 F.2d at 657.

98. McMillan v. Svetanoff, 793 F.2d 149 (7th Cir.), cert. denied, 479 U.S. 985 (1986).

99. Forrester v. White, 484 U.S. 219 (1988).

100. See id. at 229.

101. See id.

102. See id. at 230.

103. Ashelman v. Pope, 793 F.2d 1072 (9th Cir. 1986) (en banc); Holloway v. Walker, 765 F.2d (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 474 U.S. 1037 (1985).

104. See Holloway v. Walker, 765 F.2d 517 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 474 U.S. 1037 (1985); Dykes v. Hosemann, 776 F.2d 942 (11th Cir. 1985), cert. denied, 479 U.S. 983 (1986).

105. See Ashelman, 793 F.2d at 1077-78.

106. See supra notes 55-64 and accompanying text.

107. See Dykes, 776 F.2d at 946; Ashelman, 793 F.2d at 1077.

108. See Rankin v. Howard, 633 F.2d 844 (9th Cir. 1980), cert. denied, 451 U.S. 939 (1981).

109. See Ashelman, 793 F.2d at 1078.

110. See Holloway v. Walker, 765 F.2d 517 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 474 U.S. 1037 (1985); Dykes v. Hosemann, 776 F.2d 942 (11th Cir. 1985), cert. denied, 479 U.S. 983 (1986); see also Krempp v. Dobbs, 775 F.2d 1319 (5th Cir. 1985).

111. See Dykes, 776 F.2d at 946-48; Ashelman, 793 F.2d at 1077-78.

112. 2 J. STORY, COMMENTARIES ON EQUITY JURISPRUDENCE § 875 (11th ed. 1873).

113. Id.

114. Pulliam v. Allen, 466 U.S. 522, 529 (1984).

115. 1 W. HOLDSWORTH, A HISTORY OF ENGLISH LAW 226-31 (7th ed. 1956).

116. Gould v. Gapper, 5 East. 345, 102 Eng. Rep. 1102 (R.B. 1804); In re Hill, 10 Ex. Ch. 726 (1855).

117. Pulliam, 466 U.S. at 535-36.

118. See Pulliam, 466 U.S. at 529; R.W.T. v. Dalton, 712 F.2d 1225, 1233-34 (8th Cir.), cert. denied, 464 U.S. 1009 (1983); In re Justices of Supreme Court of Puerto Rico, 695 F.2d 17, 25-26 (1st Cir. 1982); WXYZ v. Hand, 658 F.2d 420 (6th Cir. 1981); Heimbach v. Lyons, 597 F.2d 344, 347 (2d Cir. 1979); Harris v. Harvey, 605

F.2d 330, 337 (7th Cir. 1979), cert. denied, 445 U.S. 938 (1980).

119. See Trainor v. Hernandez, 431 U.S. 424, 440-41 (1979); Judice v. Vail, 430 U.S. 327, 336-38 (1977); Huffman v. Pursue, Ltd., 420 U.S. 592, 601 (1975); Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37, 43-46 (1971).

120. See Pulliam, 466 U.S. at 537-38.

121. 466 U.S. 522 (1984).

122. Pub. L. No. 94-559, 90 Stat. 2641 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 1988 (1982)).

123. Pulliam, 466 U.S. at 543.

124. Id.

125. Id. at 543-44.

126. See O’Bryan v. Chandler, 496 F.2d 403 (10th Cir.), cert. denied, 419 U.S. 986 (1974); Ginger v. Bowles, 369 Mich. 680, 120 N.W.2d 842, cert. denied, 375 U.S. 856 (1963); Reller v. Ankeny, 160 Neb. 47, 68 N.W.2d 686 (1955); Brech v. Seacat, 84

S.D. 264, 170 N.W.2d 348 (1969).

127. See supra notes 19-25 and accompanying text.

128. See Wahler v. Schroeder, 9 Ill. App. 3d 505, 292 N.E.2d 521 (1972); Reller, 160 Neb. at 54-55; see also RESTATEMENT (SEcoND) OF ToRTS § 585 comment e (1977). 129. See M. CoMIsKY & P. PATTERSON, supra note 19, at 243.

130. Id.

131. See Rice v. Coolidge, 121 Mass. 393 (1876); Kraushaar v. Lavin, 39 N.Y.S.2d 880, 883 (Sup. Ct. 1943); Karelas v. Baldwin, 237 A.D. 265, 261 N.Y.S. 518 (1932); Houghton v. Humphries, 85 Wash. 50, 147 P. 641 (1915).

132. See supra text accompanying notes 55-64.

133. See supra text accompanying notes 65-111.

134. See Garfield v. Palmieri, 297 F.2d 526 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 369 U.S. 871 (1962); Ginger v. Bowles, 369 Mich. 680, 120 N.W.2d 842 (1963) cert. denied, 375 U.S. 856 (1963); Murray v. Brancato, 290 N.Y. 52, 48 N.E.2d 257 (1943).

135. See supra text accompanying notes 65-111.

136. See Kraushaar v. Lavin, 39 N.Y.S.2d 880, 884 (Sup. Ct. 1943).

137. Brech v. Seacat, 84 S.D. 264, 170 N.W.2d 348 (1969).

138. See Garfield, 297 F.2d at 527-28; see also McGovern v. Marty, 182 F. Supp. 343 (D.D.C. 1960). 139. See Murray v. Brancato, 290 N.Y. 52, 48 N.E.2d 257 (1943).

140. Garfield v. Palmieri, 297 F.2d 526 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 369 U.S. 871

(1962).

141. See Bradford v. Pette, 204 Misc. 308 (N.Y. 1953).

142. See Brown v. Rutledge, 20 Ga. App. 118, 92 S.E. 774 (1916); King County v. United Pac. Ins. Co., 72 Wash. 2d 604, 434 P.2d 554 (1967).

143. See Commonwealth v. Lee, 120 Ky. 433, 86 S.W. 990 (1905).

144. See Truesdale v. Bellinger, 172 S.C. 80, 172 S.E. 784 (1934).

145. See e.g., id. at 87-88, 172 S.W. at 787.

146. American Surety Co. v. Skaggs’ Guardian, 247 Ky. 687, 57 S.W.2d 495 (1983); Heyn v. Massachusetts Bonding & Ins. Co., 110 S.W.2d 261 (Tex. 1937).

147. See cases cited supra note 146.

148. See infra text accompanying notes 154-56.

149. See Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 348 (1880); Braatelien v. United States, 147 F.2d 888 (8th Cir. 1945); McFarland v. State, 172 Neb. 251, 109 N.W.2d 397 (1961).

150. Braatelien, 147 F.2d at 895; McFarland, 172 Neb. at 260, 109 N.W.2d at 404.

151. See supra text accompanying notes 55-111.

152. See Braatelien, 147 F.2d at 895; McFarland, 172 Neb. at 260, 109 N.W.2d at 404.

153. See Braatelien v. United States, 147 F.2d 888 (8th Cir. 1945); McFarland v. State, 172 Neb. 251, 109 N.W.2d 397 (1961).

154. See Hamilton v. Williams, 26 Ala. 527 (1855); Commonwealth v. Tartar, 239 S.W.2d 265 (Ky. 1951); In re McNair, 324 Pa. 48, 187 A. 498 (1936).

155. See M. COMISKY & P. PATrERSON, supra note 19, at 239.

156. See cases cited supra note 149.

157. 100 U.S. 339 (1880).

158. See id. at 348.

159. See supra text accompanying notes 86-93.

160. See Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. at 348.

161. 239 S.W.2d 265 (Ky. 1951).

162. 147 F.2d 888 (8th Cir. 1945).

163. Id. at 895.

164. Id.

165. Id.

166. 172 Neb. 251, 109 N.W.2d 397 (1961).

167. Id. at 260, 109 N.W.2d at 403.

168. Id.

169. See United States v. Issacs, 493 F.2d 1124 (7th Cir.), cert. denied, 417 U.S. 976 (1974).

170. U.S. CoNsT. art. III, § 1.

171. Issacs, 493 F.2d at 1140-44.

172. E.g., Ky. Sup. CT. R. 4.020; MICH. CONST. art. VI, § 30(2); OR. CONST. art. VII, § 8(1); WASH. REV. CODE ANN. § 9.92.120 (1988).

173. E.g., WYo. CONST. art. V, § 6(c).

174. E.g., PA. CONST. art. VI, § 7.

175. In re Callanan, 419 Mich. 376, 355 N.W.2d 69 (1984).

176. Sullivan v. State ex reL Attorney Gen., 472 So. 2d 970 (Ala. 1985).

177. In re Coruzzi, 95 N.J. 557, 472 A.2d 546 (1984).

178. In re Kivett, 309 N.C. 635, 309 S.E.2d 442 (1983).

179. In re Tindall, 60 Cal. 2d 469, 386 P.2d 473, 34 Cal. Rptr. 849 (1963), cert. denied, 377 U.S. 966 (1964).

180. State ex rel. Carroll v. Simmons, 61 Wash. 2d 146, 377 P.2d 421 (1962), cert. denied, 374 U.S. 808 (1963).

181. For a summary of modem cases involving the criminal conduct of judges, see AMERICAN JUDICATURE Soc’Y, JUDICIAL DISCIPLINE AND DISABILITY DIGEST 355-58 (1981).

182. See State ex rel. Carroll v. Simmons, 61 Wash. 2d 146, 377 P.2d 421 (1962), cert. denied, 374 U.S. 808 (1963); In re Callanan, 419 Mich. 376, 355 N.W.2d 69 (1984).

183. WASH. REV. CODE ANN. § 9.92.120 (1988).

184. E.g., CAL. CONsT. art. VI, § 18.

185. See Gruenburg v. Kavanagh, 413 F. Supp. 1132 (E.D. Mich. 1976).

186. E.g., MICH. CT. R. 9.220.

187. E.g., WASH. REV. CODE ANN. § 9.92.120 (1988).

188. MODEL CODE OF JUDICIAL CONDucT Canon 1 (1972).

189. ‘Id. Canon 2.

190. See In re Wireman, 270 Ind. 344, 367 N.E.2d 1368 (1977), cert. denied, 436 U.S. 904 (1978); In re Callanan, 419 Mich. 376, 355 N.W.2d 69 (1984); In re Duncan, 541 S.W.2d 564 (Mo. 1976); In re Hunt, 308 N.C. 328, 302 S.E.2d 235 (1983); W. Va. Judicial Inquiry Comm’n v. Dostert, 165 W. Va. 233, 271 S.E.2d 427 (1980).

191. In re Van Susteren, 118 Wis. 2d 806, 348 N.W.2d 579 (1984).

192. In re Maxwell, 287 S.C. 594, 340 S.E.2d 541 (1986).

193. Id.

194. In re Killam, 388 Mass. 619, 447 N.E.2d 1233 (1983).

195. Starnes v. Judicial Retirement & Removal Comm’n, 680 S.W.2d 922 (Ky. 1984); In re Whitaker, 463 So. 2d 1291 (La. 1985).

196. In re Robert Dean Hawkins, (Unreported Order, Judicial Retirement & Removal Comm’n, Ky. Nov. 28, 1984).

197. In re Callanan, 419 Mich. 376, 355 N.W.2d 69 (1984); In re Raineri, 102 Wis. 2d 418, 306 N.W.2d 699 (1981).

198. In re Roth, 293 Or. 179, 645 P.2d 1064 (1982).

199. Roberts v. Comm’n on Jud. Performance, 33 Cal. 3d 739, 661 P.2d 1064, 190 Cal. Rptr. 910 (1983).

200. In re Inquiry Concerning A Judge No. 491, 249 Ga. 30, 287 S.E.2d 2 (1982).

201. 388 Mass. 619, 447 N.E.2d 1233 (1983).

202. Id. at 622, 447 N.E.2d at 1235-36.

203. Id. at 623, 447 N.E.2d at 1236.

204. 249 Ga. 30, 287 S.E.2d 2 (1982).

205. Id. at 31, 287 S.E.2d at 4.

206. Id.

207. See In re Burns (Unreported Judgment COJ-7, Ala. Ct. Jud., July 18, 1977); In re Inquiry Concerning A Judge No. 491, 249 Ga. 30, 287 S.E.2d 2 (1982); Louisiana State Bar Ass’n v. Funderburk, 284 So. 2d 564 (La. 1973); In re Szymanski, 400 Mich. 469, 255 N.W.2d 601 (1977); In re Bates, 555 S.W.2d 420 (Tex. 1977). In re Biggins, 153 Ariz. 439, 737 P.2d 1077 (1987); McComb v. Comm’n on Jud. Performance, 19 Cal. 3d 1, 564 P.2d 1, 138 Cal. Rptr. 459 (1977);

208. See cases cited supra note 207.

209. See In re Haddad, 128 Ariz. 490, 492, 627 P.2d 221, 223 (1981).

210. See id.; In re Kelley, 238 So. 2d 565, 569 (Fla. 1970), cert. denied, 401 U.S. 962 (1971); In re Benoit, 487 A.2d 1158 (Me. 1985); In re Storie, 574 S.E.2d 369 (Mo. 1978); In re Wright, 313 N.C. 495, 329 S.E.2d 668 (1985).

211. See Kelley, 238 So. 2d at 569.

212. See Benoit, 487 A.2d at 1174;’In re Diener, 268 Md. 659, 304 A.2d 587 (1973), cert. denied, 415 U.S. 989 (1974); Sharpe v. State, 448 P.2d 301 (Okla. 1968), cert. denied, 394 U.S. 904 (1969); In re Coruzzi, 95 N.J. 557, 472 A.2d 546, appeal dismissed, 469 U.S. 802 (1984); Wright, 313 N.C. at 499, 329 S.E.2d at 671.

213. Kelley, 238 So. 2d at 569.

214. See People v. La Carrubba, 46 N.Y.2d 658, 661, 416 N.Y.S.2d 203, 206, 389 N.E.2d 799, 802 (1979); see also cases cited supra note 207.

215. E.g., In re Haddad, 128 Ariz. 490, 492, 627 P.2d 221, 223 (1981); Coruzzi, 95 N.J. at 570, 472 A.2d at 557.

216. See I. TESITOR & D. SINKS, JUDICIAL CONDUCT ORGANIZATIONS 3 (2d ed. 1980).

217. See In re Sanford, 352 So. 2d 1126, 1128-29 (Ala. 1977); In re Ross, 428 A.2d 858, 860 (Me. 1981); In re Judge Anonymous, 590 P.2d 1181, 1188 (Okla. 1978).

218. In re Burns (Unreported Judgment COJ-7, Ala. Ct. Jud., July 18, 1977); In re Biggins, 153 Ariz. 439, 737 P.2d 1077 (1987); McComb v. Comm’n on Jud. Performance, 19 Cal. 3d 1, 564 P.2d 1, 138 Cal. Rptr. 459 (1977); In re Inquiry Concerning A Judge No. 491, 249 Ga. 30, 287 S.E.2d 2 (1982); Louisiana State Bar Ass’n v. Funderburk, 284 So. 2d 564 (La. 1973); In re Szymanski, 400 Mich. 469, 255 N.W.2d 601 (1977); In re Bates, 555 S.W.2d 420 (Tex. 1977).

219. 555 S.W.2d 420 (Tex. 1977).

220. Id. at 428.

221. 19 Cal. 3d Spec. Trib. Supp. 1, 564 P.2d 1, 138 Cal. Rptr. 459 (1977).

222. Id. at 9, 564 P.2d at 5, 138 Cal. Rptr. at 463.223. 374 Mich. 104, 131 N.W.2d 201 (1964).

224. Id. at 105, 131 N.W.2d at 203.

225. 34 N.J. 259, 168 A.2d 38 (1961).

226. Id. at 266, 168 A.2d at 42.

227. Id.

228. 542 S.W.2d 105 (Tex. 1976).

229. Id. at 108; see also In re Mussman, 112 N.H. 99, 289 A.2d 403 (1972).

230. See In re Biggins, 153 Ariz. 439, 737 P.2d 1077 (1987); In re Inquiry Concerning A Judge No. 491, 249 Ga. 30, 287 S.E.2d 2 (1982); Louisiana State Bar Ass’n v. Funderburk, 284 So. 2d 564 (La. 1973); In re Callanan, 419 Mich. 376, 355 N.W.2d 69 (1984).

231. 284 So. 2d 564 (La. 1973).

232. 153 Ariz. 439, 737 P.2d 1077 (1987).233. Id. at 443-44, 737 P.2d at 1081-82.

234. Id.

235. 419 Mich. 376, 355 N.W.2d 69 (1984).

236. Id. at 387-89, 355 N.W. 2d at 74.

237. N.Y.L.J., June 2, 1982 at 1, col. 5 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. May 27), modified, 91 A.D.2d 554, 457 N.Y.S.2d 33 (1982).

238. Friess, N.Y.L.J., June 2, 1982 at 7, col. 2.

239. Id.

240. Id.

241. 91 A.D.2d 554, 457 N.Y.S.2d 33 (1982).

242. Id. at 556, 457 N.Y.S.2d at 35.

243. Id.

download PDF Here

To Learn More…. Read MORE Below and click the links Below

Abuse & Neglect – The Reporters (Police, D.A & Medical & the Bad Actors)

Mandated Reporter Laws – Nurses, District Attorney’s, and Police should listen up

If You Would Like to Learn More About: The California Mandated Reporting LawClick Here

To Read the Penal Code § 11164-11166 – Child Abuse or Neglect Reporting Act – California Penal Code 11164-11166Article 2.5. (CANRA) Click Here

Mandated Reporter formMandated ReporterFORM SS 8572.pdf – The Child Abuse

ALL POLICE CHIEFS, SHERIFFS AND COUNTY WELFARE DEPARTMENTS INFO BULLETIN:

Click Here Officers and DA’s for (Procedure to Follow)

It Only Takes a Minute to Make a Difference in the Life of a Child learn more below

You can learn more here California Child Abuse and Neglect Reporting Law its a PDF file

Learn More About True Threats Here below….

We also have the The Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) – 1st Amendment

CURRENT TEST = We also have the The ‘Brandenburg test’ for incitement to violence – 1st Amendment

We also have the The Incitement to Imminent Lawless Action Test– 1st Amendment

We also have the True Threats – Virginia v. Black is most comprehensive Supreme Court definition – 1st Amendment

We also have the Watts v. United States – True Threat Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Clear and Present Danger Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Gravity of the Evil Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Elonis v. United States (2015) – Threats – 1st Amendment

Learn More About What is Obscene…. be careful about education it may enlighten you

We also have the Miller v. California – 3 Prong Obscenity Test (Miller Test) – 1st Amendment

We also have the Obscenity and Pornography – 1st Amendment

Learn More About Police, The Government Officials and You….

$$ Retaliatory Arrests and Prosecution $$

We also have the Brayshaw v. City of Tallahassee – 1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Publius v. Boyer-Vine –1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, Florida (2018) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Nieves v. Bartlett (2019) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Hartman v. Moore (2006) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

We also have the Reichle v. Howards (2012) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

We also have the Freedom of the Press – Flyers, Newspaper, Leaflets, Peaceful Assembly – 1st Amendment

We also have the Insulting letters to politician’s home are constitutionally protected, unless they are ‘true threats’ – Letters to Politicians Homes – 1st Amendment