Libel and Slander – 1st Amendment

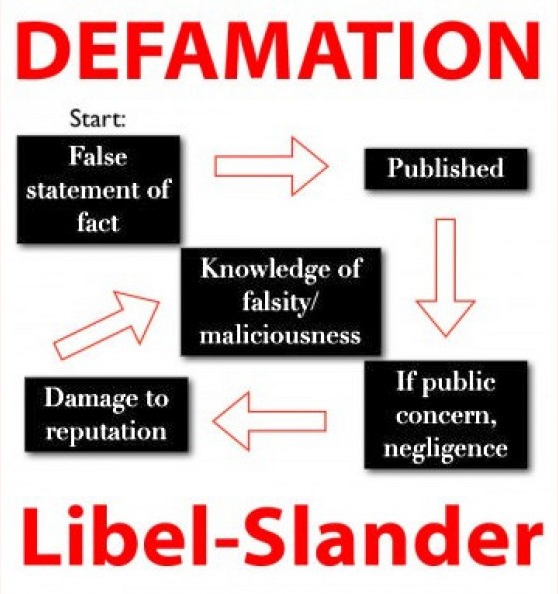

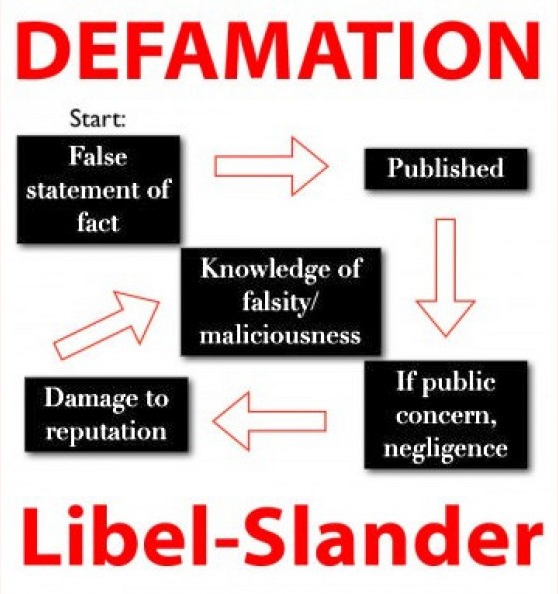

Defamation is a tort that encompasses false statements of fact that harm another’s reputation.

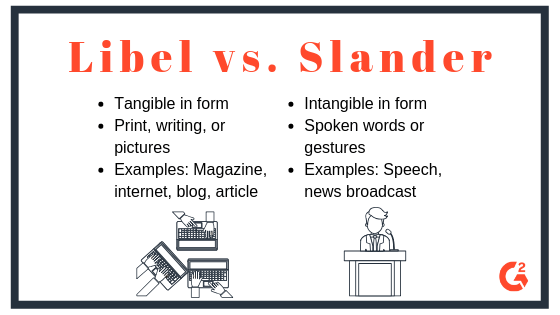

There are two basic categories of defamation: (1) libel and (2) slander. Libel generally refers to written defamation, while slander refers to oral defamation, though much spoken speech that has a written transcript also falls under the rubric of libel.

The First Amendment rights of free speech and free press often clash with the interests served by defamation law. The press exists in large part to report on issues of public concern. However, individuals possess a right not to be subjected to falsehoods that impugn their character. The clash between the two rights can lead to expensive litigation, million-dollar jury verdicts and negative public views of the press.

Right to protect one’s good name is heart of defamation law

Defamatory comments might include false comments that a person committed a particular crime or engaged in certain sexual activities.

The hallmark of a defamation claim is reputational harm. Former United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart once wrote that the essence of a defamation claim is the right to protect one’s good name. He explained in Rosenblatt v. Baer (1966) that the tort of defamation “reflects no more than our basic concept of the essential dignity and worth of every human being — a concept at the root of any decent system of ordered liberty.”

Defamation suits can have chilling effect on free speech

However, defamation suits can threaten and test the vitality of First Amendment rights. If a person fears that she can be sued for defamation for publishing or uttering a statement, he or she may avoid uttering the expression – even if such speech should be protected by the First Amendment.

This “chilling effect” on speech is one reason why there has been a proliferation of so-called “Anti-SLAPP” suits to allow individuals a way to fight back against these baseless lawsuits that are designed to silence expression. Professors George Pring and Penelope Canaan famously referred to them as Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation or SLAPP suits.

Because of the chilling effect of defamation suits, Justices William O. Douglas, Hugo Black, and Arthur Goldberg argued for absolute protection at least for speech about matters of public concern or speech about public officials. The majority of the Court never went this far and instead attempted to balance or establish an accommodation between protecting reputations and ensuring “breathing space” for First Amendment freedoms. If the press could be punished for every error, a chilling effect would freeze publications on any controversial subject.

Libel was once viewed as unprotected by First Amendment

Before 1964, state law tort claims for defamation weighed more heavily in the legal balance than the constitutional right to freedom of speech or press protected by the First Amendment. Defamation, like many other common-law torts, was not subject to constitutional baselines.

In fact, the Supreme Court famously referred to libel in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942) as an unprotected category of speech, similar to obscenity or fighting words. Justice Frank Murphy wrote for a unanimous Court that “[t]here are certain well-defined and narrowly limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which has never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem. These include the lewd and obscene, the profane, the libelous, and the insulting or ‘fighting’ words.”

Libel carried criminal penalties in early America

American and English law had a storied tradition of treating libel as wholly without any free-speech protections. In fact, libel laws in England and the American colonies imposed criminal, rather than civil, penalties. People were convicted of seditious libel for speaking or writing against the King of England or colonial leaders. People could be prosecuted for blasphemous libel for criticizing the church.

Even truth was no defense to a libel prosecution. In fact, some commentators have used the phrase “the greater the truth, the greater the libel” to describe the state libel law. The famous trial of John Peter Zenger in 1735 showed the perils facing a printer with the audacity to criticize a government leader.

Zenger published articles critical of New York Governor William Cosby. Cosby had the publisher charged with seditious libel. Zenger’s defense attorney, Andrew Hamilton, persuaded the jury to engage in one of the first acts of jury nullification and ignore the principle that truth was no defense.

The Zenger case was more of an outlier than a trend. It did not usher in a new era of freedom. Instead, as historian Leonard Levy explained in his book Emergence of a Free Press (1985) that “the persistent notion of Colonial America as a society where freedom of expression was cherished is an hallucination which ignores history. … The American people simply did not believe or understand that freedom of thought and expression means equal freedom for the other person, especially the one with hated ideas.”

Sedition Act of 1798 passed to silence opposition regarding France

Even though the First Amendment was ratified as part of the Bill of Rights in 1791, a Federalist-dominated Congress then passed the Sedition Act of 1798, which was designed to silence political opposition in the form of those Democratic-Republicans who favored better American relations with France.

The draconian law prohibited “publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government … with intent to defame … or to bring them … into contempt or disrepute.” The law was used to silence political opposition.

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan changed libel law nationally

Until the later half of the 20th century, the law seemed to favor those suing for reputational harm. For most of the 20th century, a defendant could be civilly liable for defamation for publishing a defamatory statement about (or “of and concerning”) the plaintiff. A defamation defendant could be liable even if he or she expressed her defamatory comment as opinion. In many states, the statement was presumed false and the defendant had the burden of proving the truth of his or her statement. In essence, defamation was closer to the concept of strict liability than it was to negligence, or fault.

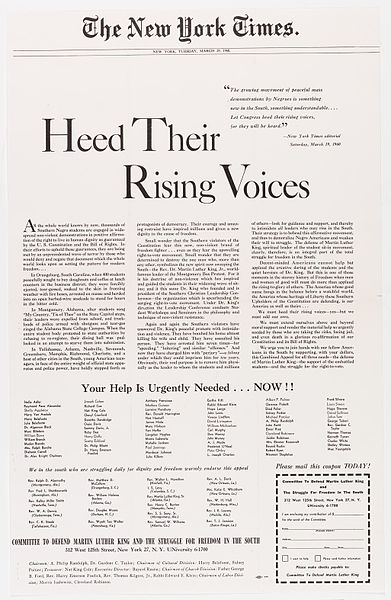

However, in the celebrated case of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the U.S. Supreme Court constitutionalized libel law. The case arose out of the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement. The New York Times published an editorial advertisement in 1960 titled “Heed Their Rising Voices” by the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King. The full-page ad detailed abuses suffered by Southern black students at the hands of the police, particularly the police in Montgomery, Alabama.

Newspaper ad contained factual errors

Two paragraphs in the advertisement contained factual errors. For example, the third paragraph read:

“In Montgomery, Alabama, after students sang ‘My Country, Tis of Thee’ on the State Capitol steps, their leaders were expelled from school, and truckloads of police armed with shotguns and teargas ringed the Alabama State College Campus. When the entire student body protested to state authorities by refusing to re-register, their dining hall was padlocked in an attempt to starve them into submission.”

The paragraph contained undeniable errors. Nine students were expelled for demanding service at a lunch counter in the Montgomery County Courthouse, not for singing ‘My Country, ‘Tis of Thee’ on the state capitol steps. The police never padlocked the campus-dining hall. The police did not “ring” the college campus. In another paragraph, the ad stated that the police had arrested Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. seven times. King had been arrested four times.

Even though he was not mentioned by name in the article, L.B. Sullivan, the city commissioner in charge of the police department, sued the New York Times and four individual black clergymen who were listed as the officers of the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King.

Sullivan wins libel claim in Alabama state court

Sullivan demanded a retraction from the Times, which was denied. The paper did print a retraction for Alabama Gov. John Patterson. After not receiving a retraction, Sullivan then sued the newspaper and the four clergymen for defamation in Alabama state court.

The trial judge submitted the case to the jury, charging them that the comments were “libelous per se” and not privileged. The judge instructed the jury that falsity and malice are presumed. He also said that the newspaper and the individual defendants could be held liable if the jury determined they had published the statements and that the statements were “of and concerning” Sullivan.

The all-white state jury awarded Sullivan $500,000. After this award was upheld by the Alabama appellate courts, The New York Times appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

U.S. Supreme Court says Alabama libel law cannot violate First Amendment

The high court reversed, finding that the “law applied by the Alabama courts is constitutionally deficient for failure to provide the safeguards for freedom of speech and of the press that are required by the First and Fourteenth Amendments in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct.”

For the first time, the Supreme Court ruled that “libel can claim no talismanic immunity from constitutional limitations,” but must “be measured by standards that satisfy the First Amendment.” In oft-cited language, Justice William Brennan wrote for the Court:

Thus, we consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.

The Court reasoned that “erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate” and that punishing critics of public officials for any factual errors would chill speech about matters of public interest. The high court also established what has come to be known as “the actual malice rule.” This means that public officials suing for libel must prove by clear and convincing evidence that the speaker made the false statement with “actual malice” — defined as “knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

Supreme Court extends new ‘actual malice’ standard for public officials to public figures

The high court extended the rule for public official defamation plaintiffs in the consolidated cases of Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts and The Associated Press v. Walker (1967).

The cases featured plaintiffs Wally Butts, former athletic director of the University of Georgia, and Edwin Walker, a former general who had been in command of the federal troops during the school desegregation event at Little Rock, Arkansas, in the 1950s.

Because the Georgia State Athletic Association, a private corporation, employed Butts, and Walker had retired from the armed forces at the time of their lawsuits, they were not considered public officials. The question before the Supreme Court was whether to extend the rule in Times v. Sullivan for public officials to public figures.

Five members of the Court extended the Times v. Sullivan rule in cases involving “public figures.”

Justice John Marshall Harlan II and three other justices would have applied a different standard and asked whether the defamation defendant had committed “highly unreasonable conduct constituting an extreme departure from the standards investigation and reporting ordinarily adhered to by responsible publishers.” The Court ultimately held that Butts and Walker were public figures.

However, sometimes the Court found that individuals were more private than public.

Court creates different standard for private figures

The Supreme Court clarified the limits of the “actual malice” standard and the difference between public and private figures in defamation cases in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974).

The case involved a well-known Chicago lawyer named Elmer Gertz who represented the family of a young man killed by police officer Richard Nuccio. Gertz took no part in Nuccio’s criminal case in which the officer was found guilty of second-degree murder.

Robert Welch, Inc. published a monthly magazine, American Opinion, which served as an outlet for the views of the conservative John Birch society. The magazine warned of a nationwide conspiracy of communist sympathizers to frame police officers. The magazine contained an article saying that Gertz had helped frame Nuccio. The article said Gertz was a communist.

The article contained several factual misstatements. Gertz did not participate in any way to frame Nuccio. Rather, he was not involved in the criminal case. He also was not a Communist.

Gertz sued for defamation. The court had to determine what standard to apply for private persons and so-called limited purpose public figures. Then, the court had to determine whether Elmer Gertz was a private person or some sort of public figure.

Magazine argues that statements related to public concern should have higher libel protections

The media defendant argued that the Times v. Sullivan standard should apply to any defamation plaintiff as long as the published statements related to a matter of public importance. Justice Brennan had taken this position in his plurality opinion in Rosenbloom v. Metromedia (1971).

The Court sided with Gertz on this question and found a difference between public figures and private persons.

The court noted two differences:

- Public officials and public figures have greater access to the media in order to counter defamatory statements; and

- Public officials and public figures to a certain extent seek out public acclaim and assume the risk of greater public scrutiny.

Court explains standards for private persons, limited-purpose public figures

For these reasons, the court set up a different standard for private persons:

We hold that, so long as they do not impose liability without fault, the States may define for themselves the appropriate standard of liability for a publisher or broadcaster of defamatory falsehood injurious to a private individual.

This standard means that a private person does not have to show that a defendant acted with actual malice in order to prevail in a defamation suit. The private plaintiff usually must show simply that the defendant was negligent, or at fault. However, the high court also ruled that private defamation plaintiffs could not recover punitive damages unless they showed evidence of actual malice.

In its opinion, the Court also determined that certain persons could be classified as limited-purpose public figures with respect to a certain controversy. The Court noted that full-fledged public figures achieve “pervasive fame or notoriety.” However, the court noted that sometimes an individual “injects himself or is drawn into a particular public controversy and thereby becomes a public figure for a limited range of issues.” Importantly, these limited-purpose public figures also have to meet the actual-malice standard.

The high court then addressed the status of Gertz. The high court determined that he was a private person, not a limited-purpose public figure. “He took no part in the criminal prosecution of Officer Nuccio,” the court wrote. “Moreover, he never discussed either the criminal or civil litigation with the press and was never quoted as having done so.”

Most important issue in defamation case is determining status of plaintiff

These cases show that perhaps the most important legal issue in a defamation case is determining the status of the plaintiff. If the plaintiff is a public official, public figure or limited-purpose public figure, the plaintiff must establish that the defendant acted with actual malice with clear and convincing evidence. However, as Judge Robert Sack wrote in his treatise on Defamation law: “Determining who is a ‘public’ figure raises more difficult questions.” (Sack, §1.5).

In several defamation cases, the Court found that individuals were private figures instead of public officials. For example, the Court ruled that a scientist who had received a research grant from the federal government was a private figure in Hutchinson v. Proxmire (1979). Similarly, in Time v. Firestone (1976), the Court held that the wife of a wealthy industrialist was a private figure.

If the plaintiff is merely a private person, the plaintiff must usually only show that the defendant acted negligently. If the private person wants to recover punitive damages, he or she must show evidence of actual malice.

Basic requirements of a defamation case

A defamation plaintiff must usually establish the following elements to recover:

- Identification: The plaintiff must show that the publication was “of and concerning” himself or herself.

- Publication: The plaintiff must show that the defamatory statements were disseminated to a third party. In slander cases, this generally means that the speaker’s defamatory comments must be heard by a third party.

- Defamatory meaning: The plaintiff must establish that the statements in question were defamatory. For example, the language must do more than simply annoy a person or hurt a person’s feelings. But, one court reasoned that calling an attorney “an ambulance chaser” does have a defamatory meaning, because it essentially is accusing the lawyer of violating the rules of professional conduct, which limit solicitation.

- Falsity: The statements must be false; truth is a defense to a defamation claim. Generally, the plaintiff bears the burden of proof of establishing falsity.

- Statements of fact: The statements in question must be objectively verifiable as false statements of fact. In other words, the statements must be provable as false.

- Damages: The false and defamatory statements must cause actual injury or special damages.

Defenses and privileges in a defamation case

There are numerous defenses and privileges to a defamation claim. These defenses can be either absolute or qualified. Many of these vary from state to state. Sometimes, a particular party has carte blanche to make certain statements even if they are false. This is called an absolute privilege. Other privileges can be established as long as certain conditions are met. These are called qualified privileges. Some of the more common defenses and privileges include:

Truth or substantial truth: Truth is generally a complete defense. Or stated another way, falsity is a required element of a defamation claim and, thus, truth is a defense. Many jurisdictions have adopted the substantial-truth doctrine, which protects a defamation defendant as long as the “gist” of the story is true. The substantial truth doctrine means that as long as the bulk of a statement is true, the defendant has not committed defamation.

Statements in judicial, legislative, and administrative proceedings: Defamatory statements made in these settings by participants are considered absolutely privileged. For example, a lawyer in a divorce case could not be sued for libel for comments he or she made during a court proceeding. Likewise, a legislator cannot be sued for defamation for statements made in discussing bills.

Fair report or fair comment: The fair report privilege, which varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, generally provides a measure of protection to a defamation defendant who reports generally accurately about the deliberations of a public body, such as a city council or school board meeting. For the privilege to apply, the reporter’s coverage generally must be a fair abridgement of what actually occurred at the governmental meeting.

Libel-proof plaintiffs: This defense holds that some plaintiffs have such lousy reputations that essentially they are libel-proof. The theory is that one cannot harm someone’s reputation when that person already has a damaged reputation. For example, those with extensive criminal records could be considered libel-proof.

Rhetorical hyperbole: Rhetorical hyperbole is a First Amendment-based defense that sometimes can provide protection for a defamation defendant who engages in exaggerated and hyperbolic expression. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court once ruled in Letter Carriers v. Austin (1974) that a union’s use of the word “scab” was a form of rhetorical hyperbole. Some courts will hold that certain language in certain contexts (editorial/opinion column) is understood by the readers to be figurative language not to be interpreted literally.

Retraction statutes: Nearly every state possesses a retraction statute that allows a defamation defendant to retract, or take back, a libelous publication. Some of these statutes bar recovery, while others prevent the plaintiff from recovering so-called punitive damages if the defendant properly complies with the statute.

Defamation, like many other torts, varies from state to state. For example, states recognize different privileges and apply different standards with respect to private-person plaintiffs. Interested parties or practitioners must carefully check the case law of their respective state.

Defamation suits can further important interests of those who have been victimized by malicious falsehoods. However, defamation suits can also threaten First Amendment values by chilling the free flow of information. Once again, this is why many states have responded to the threat of meritless defamation suits by passing so-called Anti-SLAPP statutes.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a First Amendment Fellow at the Freedom Forum Institute and a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was published May 14, 2020.

By David L. Hudson Jr. cited https://mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/997/libel-and-slander

Libel-Proof Plaintiff Doctrine – 1st Amendment

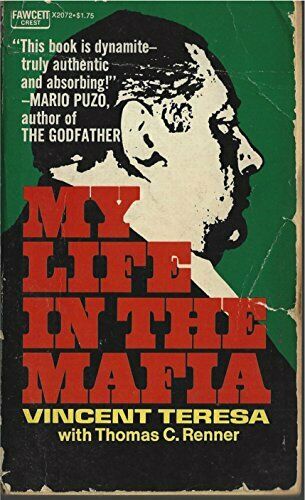

The libel-proof plaintiff doctrine is a concept that insulates a speaker or publisher from liability for statements made about someone who has no good reputation to protect. The hallmark of a defamation claim is reputational harm. If a person has no reputation to protect, then he or she may be considered “libel-proof.”

If a plaintiff has no reputation to protect, they may be considered ‘libel-proof’

Judge Robert Sack, in his treatise Sack on Defamation: Libel, Slander and Related Problems, describes the doctrine as “a notorious person is without a good name and therefore may not recover for injury to it.” (§2.4.18).

The libel-proof plaintiff doctrine is related to the incremental harm doctrine, which provides that when many true statements accompany a false statement, the incremental harm done by the false statement is negligible.

Some state court decisions refer to two types of libel-proof claims: (1) the issue-specific approach and the (2) incremental harm approach.” (Hudson, 15). Whatever additional labels placed on the doctrine, the essence is that a defamation plaintiff is libel proof if he or she has no good reputation to protect.

Court has said a mobster, other criminals have no good reputation to protect

The Second U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals used the doctrine to hold that a mobster had no good reputation to protect in Cardillo v. Doubleday & Co. (1975). Cardillo sued a book publisher for statements made about him by another organized crime figure. The book alleged that Cardillo had fixed horse races and committed other crimes. Cardillo sued for libel, but the federal appeals court rejected his claim, writing that he was “libel-proof” because he was a “habitual criminal.”

Other courts have applied the libel-proof plaintiff doctrine to murderers, convicted thieves, and those with numerous narcotics convictions.

The doctrine should be applied narrowly. “Convicted murderers and certain inveterate criminals are one thing, but applying the doctrine to anyone with a felony on their record would be problematic.” (Hudson, 16).

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a First Amendment Fellow at the Freedom Forum Institute and a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was published June 2, 2020.

By David L. Hudson, Jr. cited https://mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1816/libel-proof-plaintiff-doctrine

The terms libel, slander, and defamation are frequently confused with each other. They are all similar in that they all fall into the same general area of law that concerns false statements which harm a person’s reputation. This general area of law is called defamation law. Libel and slander are types of defamatory statements. Libel is a defamatory statement that is written. Slander is a defamatory statement that is oral.

Historically, the distinction between libel and slander was significant and had real-world implications regarding how a case was litigated including the elements that had to be proven and who had the burden of proof. Illinois courts have changed their approach, however, as the Illinois Supreme Court explained in Bryson v. News America Publication, Inc.:

At common law, libel and slander were analyzed under different sets of standards, with libel recognized as the more serious wrong. Illinois law evolved, however, and rejected this bifurcated approach in favor of a single set of rules for slander and libel. Libel and slander are now treated alike and the same rules apply to a defamatory statement regardless of whether the statement is written or oral.

The tort of defamation (sometimes referred to as defamation of character) can be divided into claims involving two distinct types of statements: defamatory per se statements and defamatory per quod statements. Statements that are defamatory per se (sometimes referred to generically by courts as libel per se) are so obviously and naturally harmful to one’s reputation on their face that proof of injury is not required. Illinois law recognizes five types of statements that are considered defamatory per se:

- Imputing that a person committed a crime;

- Imputing that a person is infected with a loathsome communicable disease;

- Imputing that a person is unable or lacks the integrity to perform one’s employment duties;

- Imputing that a person lack ability or otherwise prejudices one in one’s profession; and

- Imputing that a person has engaged in adultery or fornication.

Importantly, a statement can only be considered defamatory per se if the harmful effect is apparent on the face of the statement itself. If extrinsic facts or additional information about the person being defamed is required to understand the harmful effect of the statement, then it cannot be defamatory per se. That is not to say the statement is not defamatory if extrinsic facts are required; it just cannot be defamatory per se.

If a defamatory statement does not fall into one of the defamatory per se categories or requires extrinsic facts, then it is considered defamatory per quod. Unlike in cases involving defamation per se, defamation per quod claims require the plaintiff to allege and prove special damages (also called “special harm” by some courts). The term “special damages” or “special harm” is a legal term of art in defamation law that means the loss of something with actual economic or pecuniary value. In other words, a plaintiff alleging defamation per quod must be able to show specifically how the defamation caused a specific, quantifiable loss of money such as the commission from a lost sale or the salary from a lost job. source

California Defamation (Libel and Slander) Laws

To establish a defamation claim in California, you must prove four facts:

- That someone made a false statement of purported fact about you:

- That the statement was made (published) to a third party;

- That the person who made the statement did so negligently, recklessly or intentionally; and,

- That as a result of the statement, your reputation was damaged.

California law recognizes two types of defamation:

- libel and

- slander.

The main difference is whether a defamatory statement was made

- verbally (constituting slander) or

- in writing or other tangible medium (constituting libel).

1. What is the difference between defamation, libel and slander under California law?

Defamation is an invasion of the interest in reputation. Under California law, it is a broad term for false statements made that cause damage to someone’s good standing.

California Civil Code (Cal. Civ. Code) §44 states that defamation is affected by either libel or slander.1 If a statement is made verbally, it is slander. If made in writing, it is libel.

Cal. Civ. Code §45 and Cal. Civ. Code §46 provide the definitions for both libel and slander:

Libel is a false and unprivileged publication by writing, printing, picture, effigy, or other fixed representation to the eye, which exposes any person to hatred, contempt, ridicule, or obloquy, or which causes him to be shunned or avoided, or which tends to injure him in his occupation.

In some states, libel can sometimes be charged as a crime and be punishable by a fine and jail time. However, in California, people who have been defamed are limited to their right to recover damages in a civil lawsuit.

According to Cal. Civ. Code §46, slander is “a false and unprivileged publication, orally uttered,” that does one or more of the following:

- Charges you with a crime…;

- Imputes in you the existence of an infectious, contagious, or loathsome disease;

- Tends directly to injure you in respect to your office, profession, trade or business…;

- Imputes to you impotence or a want of chastity; or

- Which, by natural consequence, causes damage.2

Unlike libel, statutory rules for slander carve out certain types of oral comments that are deemed injurious.

Again, both libel and slander are different types of defamation.

2. What are the elements of a California defamation case?

In California, you must prove five elements to establish a defamation claim:

- An intentional publication of a statement of fact;

- That is false;

- That is unprivileged;

- That has a natural tendency to injure or causes “special damage;” and,

- The defendant’s fault in publishing the statement amounted to at least negligence.

2.1 Intentional publication of a statement of fact

Since California law treats defamation as an intentional tort, a defendant must have intended the specific publication.

A publication means communication to some third person who understands

- the defamatory meaning of the statement and

- its application to you.

A publication need not be to the public at large. A communication to a single person is sufficient.

With regards to statements of “fact,” a large issue arises in the context of whether a statement was either

- a statement of fact or

- a statement of opinion.

In general, if a defendant stated an opinion, as opposed to a fact, then there is no defamation. Over-generalizations and substantially true statements also do not generally qualify as defamation.3

However, a statement of opinion may still constitute defamation if it implies the allegation of undisclosed defamatory facts as the basis for the opinion. The main determination is whether a reasonable person could conclude that the published statements imply a provably false factual assertion.4

The determination of whether a statement expresses fact or opinion is a question of law for the trial court, unless

“the statement is susceptible of both an innocent and a libelous meaning, in which case the jury must decide how the statement was understood.”5

Note that when you sue for libel or slander, the best practice is to use the “exact words” of the defamatory statement in the pleadings. However, it may be enough in slander cases for you to convey the substance of what was said rather than the exact words.6

2.2 False publications

In California defamation lawsuits, you must present evidence that a statement of fact is provably false.

If the person who made the alleged defamatory statement was telling the truth, it is an absolute defense to an action for defamation.

For example, if a person is spreading a rumor about you, and this rumor is true, there is no defamation.

In cases involving matters of purely private concern, the burden of proving the truth is on the defendant.

A defendant does not have to show the literal truth of every word in an alleged defamatory statement. It is sufficient if the defendant proves true the substance of the charge.

In cases involving public figures or matters of public concern, the burden is on you to prove falsity.

2.3 Unprivileged publications

A statement must be unprivileged to be actionable as defamation. This is also to say that a showing of privileged communication is a defense against a defamation lawsuit.7

California courts have codified several privileged communications in Cal. Civ. Code § 47. According to this section, some examples of absolute privileged publications include statements made:

- In the proper discharge of an official duty:

- In a legislative or judicial proceeding; or

- By a fair and true report in, or a communication to, a public journal of a judicial, legislative, or another public official proceeding.

The above remain privileged no matter what, even if they include statements that would otherwise be considered defamatory. Meanwhile, the following is an example of a common interest privilege (a.k.a. conditional privilege):

- A communication, without malice, to a person interested therein,

- 1) by one who is also interested, or

- 2) by one who stands in such a relation to the person interested as to afford a reasonable ground for supposing the motive for the communication to be innocent, or

- 3) who is requested by the person interested to give the information.

This common interest privilege is a qualified privilege because it only applies to “communication without malice.”

The privilege is lost if the publication was actuated by malice. Once the defense has demonstrated that the qualified privilege applies, you have the burden of defeating it by showing malice.

Journalists, for example, have qualified privilege to write about and discuss public-interest matters. If they get the facts wrong, they should not be held liable unless they acted with actual malice.8

2.4 Injures or causes special damage

The fourth element in a California defamation action requires you to show that a publication caused injury or “special damages.” When it comes to this showing injuries or damages, California defamation cases fall into one of two categories. These include:

- Defamation “per se”

- Defamation “per quod”

2.4.1 What is defamation “per se”?

In some defamation cases, the publication or defamatory statement in question is considered so damaging that you are entitled to sue without having to prove actual damages.

Such statements constitute defamation per se under California law. Per se is a Latin term meaning “of itself.” Depending on whether the statements are written or spoken, this could be referred to as slander per se or libel per se.

California law has a broad definition of “per se” defamation. It consists of anything that is damaging on its face without further explanation. Examples include false statements that:

- call you a communist;

- claim you have an infection, contagious, or loathsome disease;

- claim you are unchaste or impotent;

- harm you in your job (business, trade, profession, office);

- accuse you of committing, being indicted for, being convicted of, or being punished for a crime;

- charge you with treachery against your associates;

- charge you with violating the confidence reposed in you.

- subject you to public contempt, hatred, or ridicule; and

- cause you to be shunned or avoided.

Most “per se” cases occur when someone falsely accuses another person of having committed a crime or being unfit to practice the person’s trade, business, or profession.9

2.4.2 What is defamation “per quod”?

In California, if a defamation case is not categorized as “per se,” it is defamation “per quod.” Per quod is a Latin term meaning by which or whereby.

If a defamatory publication is “per quod,” it means that the publication

- is not defamatory on its face and

- requires allegations and proof of special damages.

Examples of special damages might include (but are not limited to):

- lost profits;

- decreased business traffic; and/or,

- adverse employment consequences.

Defamation per quod cases require the use of extrinsic evidence or explanatory information to show the libel or slander.10

2.5 Fault needed in California defamation cases

As with any personal injury in California, the defendant must have acted with a degree of legal culpability for you to be entitled to damages. However, the level of culpability required in a California defamation case depends on whether you are a public or private figure.

When you are a private individual, you are only required to prove that the defendant was negligent in determining whether the statement at issue was true or not.

A public figure, however, is held to a higher standard. Public figures must prove affirmatively that a statement was false.

As a public figure, you must also prove “actual malice.” This means that the defendant made the defamatory statement either

- with knowledge that it was false (in other words, intentionally lied) or

- with reckless disregard for the truth.

Likewise, when an allegedly defamatory statement involves a matter of public concern (as opposed to a private matter), you have the burden to prove that the defendant acted with malice.11

2.5.1 Who is a public figure under California defamation laws?

In California, to classify a person as a public figure, the person must have achieved such pervasive fame, prominence, or notoriety in the community that they became a public figure for all purposes and in all contexts. Some examples of a public figure under California law include:

- An author;

- Public officials/politicians in government.

- A television or multi-media personality;

- The founder of a church;

- A real-estate developer; and

- Other celebrities.

California law also requires that “limited-purpose” public figures prove malice in order to prevail in a defamation claim.

A limited-purpose public figure is different than an all-purpose public figure. A limited-purpose public figure is a person who voluntarily injects themself or is drawn into a particular public controversy.12

As examples, the following persons have been considered limited-purpose public figures under California defamation law:

- The president of two corporations that opposed rezoning issues affecting his property; and,

- A self-proclaimed expert in earthquake safety.13

3. What about my right to free speech?

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution protects the right of free speech. However, this right is not absolute.

The United States Supreme Court has long held that there is “no constitutional value in false statements of fact.”

4. What are defenses to defamation in California?

There are numerous defenses available in a California defamation case. Some have been touched on already. A few of the more common defenses include:

- The defendant’s statement was true;

- The statement was not published;

- The statement was privileged;

- You gave express, informed, implied, or unanimous consent to the publication;

- The statement was an opinion or fair comment on a matter of public interest;

- The statement was not made negligently or with malice; and/or,

- The defendant never said anything negative about you.

Another potential defense is that the allegedly defamatory statement is protected under California’s Anti-SLAPP statutes. SLAPPs (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) are frivolous lawsuits filed without merit and in bad faith for the purpose of intimidating, silencing, or censoring the alleged defamer.

In order for a defamation case to be dismissed on Anti-SLAPP grounds, the court has to find that:

- The defendant was exercising their right of petition or free speech regarding a public issue, and

- You did not demonstrate any probability that you would win the defamation case.14

An experienced California defamation attorney can advise you on which, if any, defenses might apply to your defamation suit.

5. What may I recover in a California defamation case?

If you are successful in your defamation case, you may recover damages.

In general, you may be awarded three types of damages. These include:

- General damages, which are damages for your loss of reputation, shame, mortification, and hurt feelings;

- Special damages, which are damages for your property, trade, profession or occupation; or,

- Punitive damages, which are damages awarded in the discretion of the superior court or the jury, to be recovered in addition to general and special damages, and to be awarded for the sake of example and by way of punishing a defendant.

The specific type(s) of damages you may be awarded will most likely depend on the facts and circumstances of a given case.

6. How long do I have to file a defamation case?

In general, California’s statute of limitations to bring a defamation lawsuit is one year after the untrue statement was first published or spoken.15

Since California abides by the “single publication rule,” the one-year clock starts running when the defamatory statement first appears. The clock does not restart every time the same statement is subsequently published (such as through a retweet).16

Though if the defamatory statement is edited, then it is likely that the one-year clock will restart with the first publication of the revised version.17

Note that in some cases, this one-year time limit does not start running until you discover (or reasonably should have discovered) the defamation. This “discovery rule” is typically applied when the untrue statement is not public knowledge or difficult to find.18

7. Is defamation a crime?

Defamation is not a criminal offense in California. Though it is a crime in 23 other states plus the U.S. Virgin Islands.19

8. What is the Streisand effect?

The Streisand effect is when a person attempts to block information from becoming public, but this attempt only draws more attention to the information.20 Even if you end up prevailing on a defamation claim, it may be a pyrrhic victory if the case attracted more attention than the original defamation did.

Merely writing a cease and desist letter could cause damage if it ends up being published.

If you have been defamed, consult with an attorney to discuss the pros and cons of moving forward with the case and how best to keep it under the radar.

9. Related cause of action – false light

A false light claim in California creates a right to sue when someone knowingly or recklessly creates publicity about you in a way that unreasonably places you in a false light.

In general, you must prove the following elements in a false light suit:

- The defendant published some information about you;

- The information portrayed you in a false or misleading light;

- The information was highly offensive or embarrassing to a reasonable person; and,

- The defendant published the information with reckless disregard as to its offensiveness.

Public disclosure of private facts is a similar cause of action. A form of invasion of privacy, this tort occurs when a person publicly disseminates private or embarrassing facts about you, without your consent, and without a legitimate public concern for the topic.

While defamation is meant to protect you from injury to your reputation, false light is meant to protect you from the offense or embarrassment that arises from a misleading or untrue implication. (See our article on defamation vs fight light). source

Legal references:

- See California Civil Code §44.

- See California Civil Code sections § 45 & § 46. See also Mattel, Inc. v. Luce (2002) 121 Cal.Rptr.2d 794.

- Gregory v. McDonell Douglas Corp. (1976) 17 Cal.3d 596. See also Mireskandari v. Edwards Wildman Palmer LLP (

- Copp v. Paxton (1996) 45 Cal. App. 4th 829.

- Franklin v. Dynamic Details, Inc. (2004) 116 Cal.App.4th 375, 385.

- See Okun v. Superior Court (1981) 29 Cal.3d 442 (re. special pleading standards: “Nor is the allegation defective for failure to state the exact words of the alleged slander…we conclude that slander can be charged by alleging the substance of the defamatory statement.“).

- Smith v. Maldonado (1999) 72 Cal.App.4th 637, 645.

- Cal. Civ. Code § 47. Roemer v. Retail Credit Co. (1970) 3 Cal.App.3d 368, 370-371. See also Deaile v. General Telephone Co. of California (1974) 40 Cal.App.3d 841, 847-848. Note that these types of privilege are recognized under California law: absolute, fair report, neutral report, and qualified. See also Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1972) 418 US 323.

- Jimeno v. Commonwealth Home Builders (Court of Appeal, Second District, Division Two, 1920) 47 Cal. App. 660 (defining defamation per se as statements “that tend to expose the plaintiff to public hatred, contempt, ridicule, aversion, or disgrace, and to induce an evil opinion of him in the minds of right-thinking persons and deprive him of their friendly intercourse or society”). See, for example, Del Junco v. Hufnagel (Court of Appeal, Second District, Division 3, 2007) 150 Cal. App. 4th 789 (it was defamation per se when defendant said that plaintiff had insufficient medical training to operate); Albertini v. Schaefer (Court of Appeals of California, Second District, Division Four, 1979) 97 Cal. App. 3d 822 (it was defamation per se to say that an attorney was a “crook”); Montandon v. Triangle Publication, Inc. (Court of Appeals of California, First District, Division Two, 1975) 45 Cal. App. 3d 938 (it was defamation per se to call a woman a “call-girl”); Nguyen-Lam v. Cao (Court of Appeal of California, Fourth Appellate District, Division Three, 2009) 171 Cal. App. 4th 858; Bates v. Campbell (1931) 213 Cal. 438; Ray v. Citizen-News Co. (Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division One, 1936) 14 Cal. App. 2d 6; Dethlefsen v. Skull (Court of Appeal of California, First Appellate District, Division Two, 1948) 86 Cal. App. 2d 499. Note that unlike California, most states recognize only four kinds of defamation per se.

- Slaughter v. Friedman (1982) 32 Cal. 3d 149 (a dental patient’s allegations that the dentist overcharged and performed unnecessary procedures interfered with the dentist’s “economic relations with his patients”. Unlike with defamation per se, “the [statement’s] injurious character or effect [must] be established by … proof”).

- Stolz v. KSFM 102 FM (Court of Appeal of California, Third Appellate District, 1994) 30 Cal. App. 4th 195. See also Brown v. Kelly Broad. Co. (1989) 48 Cal. 3d 711, 747 (“[A] publication or broadcast by a member of the news media to the general public regarding a private person is not privileged under [Civil Code] section 47(3) regardless of whether the communication pertains to a matter of public interest. Thus, a private-person plaintiff is not required by section 47(3) to prove malice to recover compensatory damages.”).

- Copp v. Paxton (1996) 45 Cal. App. 4th 829 (Limited-purpose public figures “thrust themselves to the forefront of particular controversies in order to influence the issues involved.” Meanwhile, all-purpose public figures attract “attention and comment” on all types of public and personal matters.). Young v. CBS Broadcasting, Inc. (Court of Appeal of California, Third Appellate District, 2012) 212 Cal. App. 4th 551 (“A public official or a limited public figure must prove the defendant published defamatory statements about the plaintiff with actual malice, or, in other words, with knowledge of the statements’ falsity or in reckless disregard of their truth or falsity.“).

- Copp v. Paxton (1996) 45 Cal. App. 4th 829. Kaufman v. Fid. Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass’n (Court of Appeal of California, Fourth Appellate District, Division Two, 1983) 140 Cal. App. 3d 913.

- Lafayette Morehouse, Inc. v. The Chronicle Publ’g Co. (Court of Appeal, First District, Division Five, 1996) 37 Cal. App. 4th 855. Code of Civil Procedure 425.16.

- California Civil Procedure, Code § 340.

- Traditional Cat Ass’n, Inc. v. Gilbreath (Court of Appeal, Fourth District, Division One, 2004) 118 Cal. App. 4th 392 (“the cause of action will accrue upon the first general distribution of website publications to the public.”). Cal. Civ. Code 3425.1-3425.5.

- LegacyQuest v. Rosen (Court of Appeals of California, First District, Division One, 2012) No. A129177 (“changes to defamatory material on a website may begin a new limitations period.”).

- Shively v. Bozanich (2003) 31 Cal. 4th 1230.

- Map of States with Criminal Laws Against Defamation, ACLU. US Virgin Islands Code 1171-1183.

- Mario Cacciottolo, The Streisand Effect: When censorship backfires, BBC (June 15, 2012).

Defamation vs. False Light: What’s The Difference?

The core difference between defamation and false light is that defamation harms the victim’s reputation, while false light invades the victim’s privacy. There are many implications that come from this difference. For example, a defamatory statement only has to be made to one other person, while false light requires the disclosure to be to the wider public.

How is defamation different from a false light claim?

The main difference between a defamation claim and a claim for false light is that defamation causes reputational harm, while a disclosure in false light invades the victim’s privacy and caused emotional distress.

This difference is very nuanced. It does not sound like the two are different, at all. In fact, many states do not treat them as separate claims. However, the implications of this difference are significant. It changes:

- how widespread the disclosure has to be,

- whether it matters that the victim is a public or a private person,

- whether the defendant made the statement with reckless disregard for the truth,

- whether the statement at issue has to be offensive or embarrassing, and

- how truth can be used as a legal defense to the lawsuit.

Widespread disclosure

To be defamation, the statement only has to be made to a single other person. To be false light, it has to be a public disclosure of private facts.

What amounts to a “public disclosure” is vague. Under common law, it is a public disclosure if the offending statement was made to the public in general or to a large number of people.1

However, the number of people who must have seen or heard the statement is only one factor that courts seem to consider. In California, for example, one court found that a true statement published in a country club newsletter was not sufficiently public.2

Another court found that a letter sent to 1,000 men was sufficiently public.3 The differences between these 2 cases, though, are striking: The country club’s newsletter was only sent to members, not to the general public, while the letter was purportedly from a semi-famous actress, asked the 1,000 recipients to meet her at a time and place, and was sent without the actress’ knowledge.

Therefore, the extent of the publicity that the disclosure needs in order to support a claim for false light will depend on the circumstances of the case. For defamation, though, the libelous statement only has to be made to a single other person.

Status of victim as a public or a private figure

In defamation, it matters whether the victim is a public figure or a private one. In false light claims, it does not matter.

The status of the victim determines whether a defamatory statement must have been made with actual malice or not. Public figures have to show actual malice in order to succeed in a defamation claim.4 Private figures do not have to show actual malice, though they may still need to show that the defendant was not merely negligent.

False light claims do not differentiate between public and private figures.

Reckless disregard for the truth

The actual malice standard that is required for some defamation cases can be satisfied by showing that the defendant made the defamatory statement knowing that the statement was a falsehood, or with reckless disregard for the truth. This standard is only used when the victim was a public figure. When the defamed party was a private figure, he or she only has to show that the statement was negligent.

The actual malice standard is always used in false light claims, regardless of whether the victim was a public figure or a private individual. Victims always have to show that the defendant knew the statement would put the victim in a false light, or acted with reckless disregard for the truth.5

Offensive statement

A statement has to be offensive to a reasonable person to support a false light claim. It does not have to be offensive, at all, to support a defamation lawsuit.

Truth as a defense

Truth is always a defense to a defamation allegation. No matter how badly the statements damage the victim’s reputation, if they were true, then the person making them is not liable for libel or slander.

In a false light action, truth may only be a defense if both the statement and its implications are true. This means that true facts that insinuate something false can lead to a false claim lawsuit.6

What is defamation?

Defamation is a statement that is harmful to someone’s reputation. If the statement is made verbally, it is slander. If it is made in writing, it is libel.

In California, plaintiffs who are not public figures have to prove the following elements to win a defamation claim involving matters of public concern:

- the defendant made the statement to a third party,

- the third party reasonably understood that the statement was about the victim,

- the third party reasonably understood the meaning of the statement,

- they were false statements, and

- the defendant failed to use reasonable care to determine the truth or falsity of the statements.7

If the victim was a public figure, he or she also has to show, by clear and convincing evidence, that the defendant knew the statements were false, or had serious doubts about their veracity.8

What is a false light invasion of privacy?

The tort of false light is an invasion of privacy claim where someone publishes offensive information that is either false, or that implies something false. The name comes from the embarrassment that the victim suffers: The offensive information exposes them to the public in a false light.

In California, personal injury plaintiffs pursuing a false light lawsuit have to show that:

- the defendant publicly disclosed information or material that showed the victim in a false light,

- the false light created by the disclosure would be highly offensive to a reasonable person in the victim’s position,

- there is clear and convincing evidence that the defendant:

- knew the disclosure would create a false impression about the victim,

- acted with a reckless disregard for the truth, or

- was negligent in determining the truth of the information or whether a false impression would be created by its disclosure;

- the victim was harmed or sustained harm to his or her property, business, occupation, or profession, and

- the defendant’s conduct was a substantial factor in causing that harm.9

Many jurisdictions, like Colorado, do not have a distinct cause of action for a false light invasion of privacy tort. There, the state supreme court stopped recognizing false light cases because of their similarities with defamation law, as well as their potential to chill the Freedom of the Press and Free Speech rights under the First Amendment.10 source

Legal References:

- Santiesteban v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 306 F.2d 9 (5th Cir. 1962).

- Warfield v. Peninsula Golf & Country Club, 214 Cal.App.3d 646 (1989).

- Kerby v. Hal Roach Studios, 53 Cal.App.2d 207 (1942).

- The New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

- Time, Inc. v. Hill, 385 U.S. 374 (1967).

- Godbehere v. Phoenix News Inc., 162 Ariz. 335 (1989).

- California Civil Jury Instructions (CACI) No. 1702.

- CACI No. 1700.

- CACI No. 1802.

- Denver Publishing Company v. Bueno, 54 P.3d 893 (2002).