The Prosecutor Problem – Why Holding Prosecutors Accountable Is So Difficult

A former assistant U.S. attorney explains how prosecutors’ decisions are fueling mass incarceration — and what can be done about it.

This essay is part of the Brennan Center’s series examining the punitive excess that has come to define America’s criminal legal system.

I became a prosecutor because I don’t like bullies. I stopped being a prosecutor because I don’t like bullies.

I grew up on the south side of Chicago in an all-Black neighborhood. My family had direct experience with crime — our house was broken into, and my mother was held up at gun point. As a young Black man, I also had some bad experiences with police officers, like getting stopped for no reason, or being the object of suspicion every time I rode my bike into a white neighborhood.

So, I went into the prosecutor’s office in the District of Columbia as an undercover brother, hoping I could create change from within. I wanted to help keep people safe from criminals, and I wanted to help keep Black people as safe as possible in a racist criminal justice system.

What I instead found was that rather than changing the system, the system was changing me. Like many lawyers, I was competitive and ambitious, and the way for a young lawyer to move up in the prosecutor’s office was to lock up as many people as possible, for as long as possible. It turned out I was good at it, and I started to think of that work as the best way to serve my community.

At some point, though, I began to see things differently. Virtually all the defendants were Black or Latino. In Washington, as in many American cities, if you visit criminal court, you would think that white people don’t commit crime. I came to realize that I did not go to law school to put Black people in prison, especially for the drug crimes that I was prosecuting — crimes that white folks were also committing but didn’t get arrested for. I also didn’t feel that my work sending so many people to prison — especially Black men — was making communities any safer. On the contrary, I learned that too many prosecutors use their power in a way that has contributed to the radical increase in incarceration.

As the most powerful actors in the criminal legal system, local and federal prosecutors have a huge amount of discretion and are subject to little judicial oversight — oversight that might moderate their misuse of prosecutorial power. For example, they decide not only whether to charge someone with a crime, but if so, what crime. Even if a judge does not agree with the prosecutor’s decision to charge someone with a particular crime, the judge is powerless to undo the prosecutor’s action. Because punishment for a crime is largely determined by the sentence that lawmakers have established in the criminal code, the prosecutor often has more power over how much punishment someone convicted of a crime receives than the judge who does the actual sentencing.

Let’s say that a person has been arrested for possessing five pounds of weed (in a jurisdiction where marijuana possession and selling is criminalized). The prosecutor can choose not to charge that person (no sentence, obviously), charge them with simple possession (usually a sentence of limited duration or severity), or charge them with possession with intent to distribute, which can require — by statute — several years in prison. Most prosecutor offices are not transparent about what factors would lead them to which charging decision — and that’s assuming that the office even has uniform standards. Many don’t, and they decide these issues on an ad hoc basis, which risks allowing inappropriate considerations like race to influence who gets charged.

Plea bargaining exacerbates the problem. This is because prosecutors typically offer an accused person a “deal” to avoid going to trial. Some 95 percent of criminal cases are resolved this way. If the defendant agrees to confess their guilt, the prosecutor recommends a sentence to the judge that is less punitive than what the prosecutor would recommend if the defendant goes to trial, and loses. This threat by prosecutors — to throw the book at defendants who are found guilty — radically dilutes the defendant’s constitutional right to a trial.

Unfortunately, the Supreme Court authorized this practice in a 1978 case called Bordenkircher v. Hayes. Lewis Hayes had been charged with forgery and faced a 2-to-10-year prison sentence. Prosecutors offered to pursue a five-year sentence if Hayes pleaded guilty and saved them from “the inconvenience and necessity of a trial.” If he refused to plead guilty, prosecutors said they would seek an indictment under the Kentucky Habitual Crime Act. Because Hayes had previously been convicted of two felonies, a conviction would mandate a sentence of life imprisonment. Hayes exercised his constitutional right to a trial, prosecutors charged him under the Habitual Crime Act, and he was found guilty and sentenced to a life term.

Hayes challenged his conviction on the grounds that his 14th Amendment due process rights were violated when prosecutors threatened to re-indict him on more serious charges if he did not plead guilty to the original, less serious forgery offense. In its 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court rejected the challenge. According to the Court, the plea-bargaining system is an “important component of this country’s criminal justice system,” and so long as pleas are made “knowingly and voluntarily,” there is no constitutional violation. The Court did recognize that punishing a person because he “has done what the law plainly allows him to do” is “a due process violation of the most basic sort.” But it rejected the idea that Hayes was being punished, claiming instead that he was just being presented with “difficult choices.”

Since Bordenkircher, plea bargaining has become so institutionalized that, in a case decided in 2012, Justice Anthony Kennedy noted that plea bargaining “is not some adjunct to the criminal justice system; it is the criminal justice system.”

Prosecutors have also contributed to the racial disparities that are an endemic feature of the U.S. criminal legal system. In 2014, the Vera Institute of Justice published research that examined racial disparities at play in the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, and it concluded that “race remained a statistically significant independent factor” at most discretionary points in the legal process. In Vera’s report, based on the analysis of more than 200,000 cases, researchers found that Black and Latino people charged with drug offenses were more likely to receive more punitive plea offers than white defendants, particularly offers that included incarceration. Black and Latino defendants were also more likely than similarly situated whites and Asian Americans to be detained before trial. The study did find that prosecutors treated Black and Latino defendants more favorably in at least one respect: they were more likely than whites to have cases dismissed before they went to trial — probably, the report argued, because “police were more likely to bring them in on bogus or unsubstantiated charges” in the first place.

Many of these policies and practices are being reexamined in jurisdictions across the country, in part thanks to reformers who have won district attorney elections. The “progressive prosecutor” movement owes its start to Angela J. Davis’s 2009 book, Arbitrary Justice: The Power of the American Prosecutor, which argued that prosecutors should use their discretion to reduce mass incarceration and racial disparities.

Reform-minded prosecutors have different approaches, but they all reject incarceration as a knee-jerk response to social ills. In Chicago, Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx has declined to prosecute low-level offenses such as small-scale retail theft as felonies. In Baltimore, State’s Attorney Marilyn J. Mosby recently announced her office will no longer prosecute sex work, drug possession, and other low-level offenses. Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner requires prosecutors in his office to state on the record the costs and benefits of any prison sentences they recommend to judges. In San Francisco, District Attorney Chesa Boudin has ended the use of “three strikes” laws.

The progressive prosecutor movement is new but promising. Since prosecutors are one of the primary sources of the problem of mass incarceration and excessive punishment, they must be part of the solution. source

Paul Butler is the Albert Brick Professor in Law at Georgetown University and a MSNBC legal analyst. A former federal prosecutor, he is the author of Chokehold: Policing Black Men.

Why Holding Prosecutors Accountable Is So Difficult

Innocence Project senior litigation counsel Nina Morrison discusses prosecutorial misconduct.

“The prosecutor has more control over life, liberty and reputation than any other person in America.” – Former U.S. Attorney General and Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson

Prosecutors hold tremendous power, having wide discretion in whether or not to bring criminal charges against someone and what those charges should be. But they also have constitutional obligations to ensure that those accused of a crime receive all the evidence that might aid the accused person’s defense before trial.

Prosecutorial misconduct occurs when a prosecutor intentionally breaks a law or a code of professional ethics while prosecuting a case.

“Prosecutors have demanding jobs and high caseloads, and we recognize that they sometimes make honest mistakes,” says Innocence Project senior litigation counsel Nina Morrison. “Sometimes those mistakes are serious enough that a person convicted of a crime will be entitled to have his or her conviction thrown out, even if the prosecutor didn’t intend to violate the convicted person’s rights.”

In some of those cases, however, the violation is not an accident and rises to the level of intentional misconduct. “In a disturbing number of cases,” Morrison explains, “we have found documents or notes hidden in a prosecutor’s case file containing information that would have directly supported our client’s innocence defense, but which was held back by the prosecutor at trial and kept hidden for decades. And in other cases, credible leads to suppressed evidence can’t be pursued because the original files are destroyed, or witnesses have died or gone missing.”

Prosecutorial misconduct occurs when a prosecutor intentionally breaks a law or a code of professional ethics while prosecuting a case. While prosecutors are responsible for following the law themselves and making sure that those in law enforcement who work on an investigation or prosecution do the same, “prosecutorial misconduct” is a term typically reserved for serious and intentional violations.

It is difficult to know the full extent of the problem, in part because prosecutors often are the ones who control access to evidence needed to investigate a claim of misconduct. But we do know that some prosecutors prize winning a conviction over complying with their constitutional obligations, resulting in error and, in some cases, intentional misconduct. Despite this, there are no reliable systems for holding prosecutors accountable for their misdeeds. Under current United States Supreme Court precedent, prosecutors are frequently granted “immunity” from civil lawsuits (meaning they cannot be sued by a wrongly convicted person) even when they intentionally violate the law, making oversight by public agencies and the courts all the more critical.

“We know that official findings of misconduct represent only a fraction of the misconduct that actually occurs.”

In Berger v. United States, 295 U.S. 78 (1935), Justice Sutherland characterized prosecutorial misconduct as “overstepp[ing] the bounds of that propriety and fairness which should characterize the conduct of such an officer in the prosecution of a criminal offense.” In the years since Berger, advocates for the wrongly convicted have increasingly focused on prosecutors’ failure to disclose favorable evidence – what are known as “Brady” violations, after the 1963 case of Brady v. Maryland – as one of the most harmful and pervasive forms of prosecutorial misconduct.

In the Dewayne Brown case, for example, a long-buried email chain uncovered more than a decade after Brown’s trial revealed that the trial prosecutor, Dan Rizzo, had deliberately hidden phone records from Brown’s defense attorney that supported Brown’s alibi. Those records might have stayed hidden forever had the police officer who originally obtained them not saved and found a copy in his garage while Brown was wrongfully incarcerated on death row. It was only after the original records were turned over and Brown was released from death row that a special prosecutor assigned to the case concluded that Rizzo not only knew about the phone records before trial, but had knowingly concealed them from Brown’s defense team.

Another example is the case of Stanley Mozee and Dennis Allen, who were both exonerated in Dallas, Texas, in 2019 after spending more than 15 years in prison for a murder they did not commit. Their joint exoneration was based on documents located in the files of the trial prosecutor, Rick Jackson, showing that he’d knowingly put on false testimony from several jailhouse informants and suppressed key evidence from eyewitnesses that would have strongly supported Mozee’s and Allen’s innocence claims.

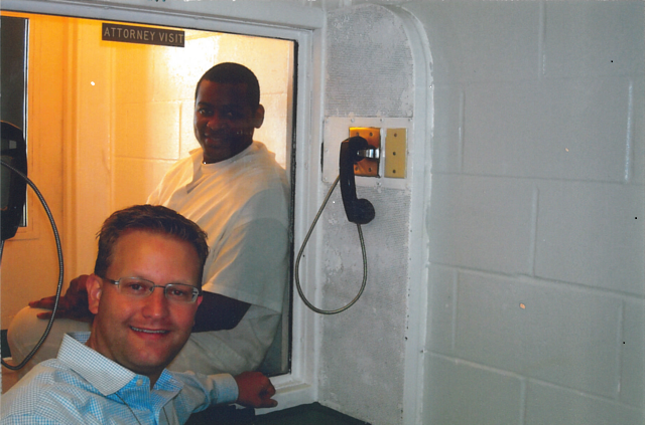

(L-R): Stanley Mozee, Conviction Integrity Unit Chief Cynthia Garza, Dallas County D.A. John Creuzot, Innocence Project Senio… Read more

A survey conducted by the Innocence Project, Innocence Project New Orleans, Resurrection After Exoneration and the Veritas Initiative looked at five diverse states over a five-year period (2004-2008) and identified 660 cases in which courts found prosecutors committed misconduct, such as tampering with key evidence, withholding evidence from the defendant or coercing a witness to give false testimony. In 527 cases, judges upheld the convictions, concluding that the prosecutorial error did not impact the fairness of the defendant’s original trial. In 133 cases, convictions were thrown out. Of the 660 cases examined, only one prosecutor accused of misconduct was disciplined.