Coerced Out of Justice: How Prosecutors Abuse Their Power to Secure Guilty Pleas

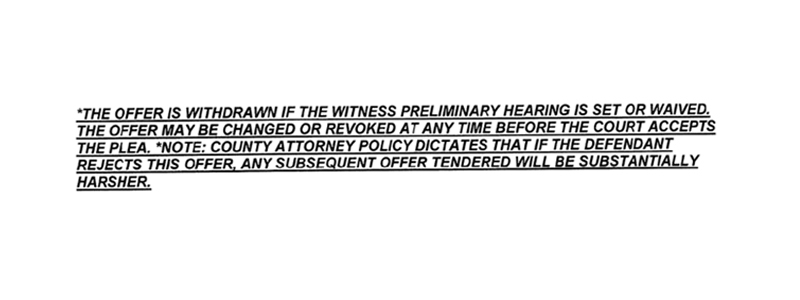

A prosecutor’s primary duty is “to seek justice … not merely to convict,” according to the American Bar Association. Prosecutors in Maricopa County’s Early Disposition Courts (EDCs) do precisely the opposite. The Maricopa County Attorney’s Office (MCAO) has an iron clad policy of making plea offers in the EDCs “substantially harsher” — their words, not ours — if an accused person seeks a preliminary hearing or rejects a plea offer to go to trial.

It doesn’t matter that the preliminary hearing — a defendant’s first opportunity to challenge whether the prosecution has enough evidence to proceed — is a right under the Arizona Constitution, or that the right to trial is enshrined in the Sixth Amendment. It also doesn’t matter if the person simply wants more evidence or is innocent of the crime. This blanket policy applies to every person in the EDCs, regardless of who they are or what they’ve done. It is also unconstitutional, and the ACLU and ACLU of Arizona are suing to stop it.

Unfortunately, if you believe your job is to convict people rather than to seek justice, this policy really gets the job done. Every year, thousands of people waive their rights and plead guilty under the weight of MCAO’s retaliation policy, terrified of receiving that “substantially harsher” offer. Worse yet, line prosecutors openly admit that the purpose of the policy is to extract quick pleas and avoid the hassle of complying with their constitutional obligations.

As one deputy county attorney put it in an email:

The purpose of EDC is to facilitate speedy resolutions … because once the case leaves EDC, MCAO must expend significant resources for trial preparation.

Another was even more blunt:

If we had to collect, review, and produce [body worn camera footage] in every case, or even the subset of cases where the defendant thought there was a legal or factual defense, given the high volume of cases in EDC, it would bog the entire system down.

Never mind that prosecutors accepted these cases from police in the first place, knowing full well they wouldn’t be able to try them while respecting the constitutional protections that defendants are entitled to.

The retaliation policy is particularly galling because Maricopa County initially created the EDCs to quickly move cases involving minor offenses or drug possession through the system and toward drug treatment and other services, in order to avoid convictions. Its website even claims that “most” EDC defendants are diverted. But this is false. MCAO’s own data shows that between 2017 and 2021, less than 7 percent of EDC cases actually ended in diversion.

Instead, MCAO funnels an ever-growing number of people through the EDCs with the express goal of quickly notching felony convictions. It’s important to note that prosecutor-led diversion is no panacea; prosecutors shouldn’t be in charge of things like drug treatment or mental health. However, it’s telling that MCAO says to the public that it supports helping people in need of treatment while quietly, quickly, and illegally convicting those people instead.

It’s clear why Maricopa prosecutors use the retaliation policy so aggressively: It’s in the best interest of prosecutors and their police partners. For example, the policy pressures the accused to waive their preliminary hearing. If MCAO doesn’t have the evidence, the hearing could kill or weaken the case, including by exposing misconduct by, or insufficient evidence from, the police. And even if the defendant doesn’t win the preliminary hearing, prosecutors must start producing more discovery thereafter. As the Arizona Supreme Court noted in 1919, the preliminary hearing exists to protect people from the “unwarranted zeal of prosecuting officers.”

It is little wonder then why MCAO is so fond of this policy: it eviscerates this vital check on their power, saves them work, avoids potential embarrassment, and still leads to convictions. In other words, the retaliation policy is the modern embodiment of the very unwarranted zeal the Arizona high court warned us about a century ago.

We are suing on behalf of all EDC defendants, now and in the future, who are either staring down the barrel of this horrific policy or have already succumbed to the unconstitutional pressure. For example, our client, Michael Calhoun, was arrested and charged for selling $20 worth of methamphetamine. Instead of diverting him into treatment — as MCAO claims is the goal of the EDCs — the office is offering him 10 years in prison. And if Mr. Calhoun rejects the offer or seeks his preliminary hearing, that draconian offer will get “substantially harsher.” He is currently weighing this unconscionable choice, terrified of dying in prison.

Coercive plea bargaining, of course, isn’t unique to Maricopa County, Arizona. Despite the constitutional guarantee of a trial by one’s peers, based on our review of MCAO data the vast majority of people nationwide who are accused of a crime resolve their case by pleading guilty. The U.S. Supreme Court has taken notice: “plea bargaining … is not some adjunct to the criminal justice system; it is the criminal justice system.” State and federal prosecutors around the country have increasingly wielded tools like mandatory minimum sentences, pretrial detention, and aggressive bargaining tactics to scare many of these people into deals they may not have taken otherwise. Coercive plea bargaining also disproportionately impacts poor and minority communities — communities that are already over-targeted by police, and often cannot afford lawyers or cash bail. This is going on everywhere; prosecutors in Maricopa are simply yelling the quiet part out loud. And we heard them.

Eliminating coercive plea bargaining is essential to ending mass incarceration. This case won’t do it alone. We need to push prosecutors and judges to be better; elect ones committed to change; and legislate away their most harmful coercive tools. This case is our first shot across that bow. source

Abuse of Power by Prosecutors

The public is becoming more aware of police abuses of power as coverage of the protests against police brutality continues. More and more people are seeing the excessive use of force wielded on protestors by police firsthand.

Abuses of power don’t just occur in the streets. They also take place in the courtroom.

What Is “Abuse of Power”?

An abuse of power happens when someone in an official position of power takes advantage of that place of privilege illegally and intentionally. When prosecutors abuse their power, it’s known as “prosecutorial misconduct.” This happens when prosecutors break the law or breach a professional code of conduct while working on a case.

The Use and Abuse of Power by Prosecutors (Justice for All)

This is a time that millions of Americans are righteously speaking out against our greatly flawed system of “criminal justice” (among other things) most recently evidenced by the horrific killing of George Floyd. Most thoughtful Americans recognize that systemic racisms stains nearly the whole fabric of our culture, but it is perhaps nowhere more obvious than in the enforcement of our criminal laws. And while necessarily robust changes may prove hard-won, recognizing and redressing specific flaws now is necessary to effect incremental changes immediately.

The full enforcement of our laws necessarily implicates individual judgments made by women and men who have taken a “sworn oath” which is, at its essence, to “render justice for all.” The color of one’s skin, their religious affiliation, their sexuality, and so on should play no role, in criminal justice since “justice is blind.”

As criminal defense attorneys, we cannot but focus on the roles played by our adversaries: prosecutors.

What Power Do Prosecutors Have?

Prosecutors wield tremendous power. They act as the government—local, state, or national—and bring the weight of that government to criminal charges against individuals and entities, which they do for the explicit purpose of taking away those individuals’ or entities’ liberties, as directed by legislation. They decide whom to charge, how to charge, what sentences the government will seek for their convictions, and what, if any, plea offer will be made. At every turn, the choices made by these women and men carry with them the potential to decimate lives, families, and communities in the pursuit of “justice.”

In making such consequential choices, these women and men are armed with unknowably complex and densely worded criminal codes prescribing the varying extents to which all manner of socially undesirable conduct may be punishable. These mammoth bodies of “criminal conduct” enable prosecutors to charge individuals with a wide array of offenses, often carrying broad degrees of possible if not mandatory punishments, for the same underlying acts. And those multiplicities of available charges and accompanying penalties empower prosecutors to impose truly enormous “trial penalties” on criminal defendants, inflating both the risks of conviction and the costs of defense, thereby distorting both sides of a criminal defendant’s cost-benefit analysis in the face of a potential plea.

And worse still, the wide menu of available charges from which to choose allows prosecutors—however consciously or unconsciously—to effect different results for the same conduct, based upon race, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, perceived social status, wealth, political connections, and all manner of other considerations which have nothing to do with justice.

How Common Is Power Abuse in the Criminal Justice System?

Unfortunately, power abuse is common in the criminal justice system—so much so that there’s a term just for when prosecutors abuse their power. This is called “prosecutorial misconduct.”

Prosecutors’ vast powers and toolkit afford them great discretion with the choices they make in any one case, and this freedom means that their personal idiosyncrasies—whether of duty to fairness, empathy, righteousness, or animus, bias, judgment, or plain weakness—have outsized impacts on how the government will treat a given subject, target, or defendant. This makes possible the aggressive pursuits of marginalized persons in the absence of concrete evidence, as with the Central Park Five, or the securing of soft landings for predacious monsters like Jeffrey Epstein. While such cases may be outlier examples, they are not as uncommon as they should be and they portend to the systemic inequalities which we all know to be true.

While many of these complaints of the criminal justice system might be better lodged upstream with the heavy-handed legislatures for their failure to invent let alone utilize functional means of deterrence other than overly-long prison sentences, prosecutors can scarcely be called innocent and cannot hide behind the shield of “just doing their job” and seeking justice. In many instances, the positions taken by these women and men are at odds with the plain intent of the laws upon which their positions are ostensibly premised, and which fly in the face of their “sworn duty” to seek justice for all.

Prosecutorial Misconduct Has Serious Consequences—for the Defendant

A specific example of this cruel and egregious harshness through choice has arisen in response to the ongoing COVID pandemic and the havoc it is wreaking within federal prisons. Unsurprisingly, the reality of an outbreak within a prison has led many federal inmates to avail themselves of the courts and seek greater safety by asking for early “compassionate release” from incarceration.

Before the enactment of the First Step Act of 2018 (“FSA”), such requests had to be brought by the Bureau of Prisons (“BOP”) on an inmate’s behalf, but the FSA explicitly enabled inmates to do so themselves if the BOP denied or failed to respond within 30 days of their request that the BOP bring that motion on their behalf. However, seemingly in reaction to the onslaught of compassionate release motions in the face of a deadly pandemic, prosecutors in U.S. Attorney’s Offices (“USAOs”) in some districts (including New Jersey), have begun inserting in defendants’ plea agreements language that would significantly impair or waive those defendants’ abilities to bring requests for compassionate release themselves.

Nothing within the meaning of “justice” can explain these waiver clauses. Rather, they seem motivated only by cruelty or a tone-deaf desire to minimize possible future paperwork. If nothing else, these waiver clauses show a clear lack of compassion and appreciation of the possibility that the justice prosecutors purport to serve might one day require an inmate’s compassionate release if faced with significant health or family emergencies which cannot be forecast at the time of sentencing.

Fortunately, defense attorneys and at least one court have recognized this plea language for it what is, a callous indifference to legislative intent and attempted usurpation of courts’ authority to show compassion when tragedy strikes after a defendant’s sentencing.

The observant court is the Northern District of California, which, in last month’s opinion in United States v. Osorto, flatly rejected a signed plea agreement due to its inclusion of the following language:

I agree not to move the Court to modify my sentence under 3582(c)(1)(A) [“compassionate release”] until I have fully exhausted all administrative rights to appeal a failure of the Bureau of Prisons to bring such a motion on my behalf, unless the BOP has not finally resolved my appeal within 180 days of my request despite my seeking review within ten days of each decision.

[U.S. v. Osorto, No. 19-cr-381-CRB-4 at *2 (N.D. Cal. May 11, 2020) (emphasis added).]

The language in the Osorto plea agreement would have added as much as 150 days, and possibly more, to the period an inmate would have had to wait between submitting a compassionate release request to the BOP and ultimately moving the court for the same relief due to the BOP’s failure or refusal to do so. Under the Osorto plea language, if the BOP failed to act on an inmate’s request, as it often does, that inmate, who might be facing an immediate health or family crisis, would have to wait nearly half a year before seeking compassionate release from the courts.

Happily, the Osorto court rejected it, finding that language “unacceptable” since it would “undermine[] Congress’s intent in passing the First Step Act” and was, simply, “inhumane.” Id. *5.

The Orsoto prosecutors should not have needed a federal judge to tell it as much. Compassionate release motions, whether brought by the BOP as originally intended or by an inmate under the FSA, require that the court find that “extraordinary and compelling reasons” warrant modifying or reducing a defendant’s sentence. The plain language of that phrase contemplates changes in circumstances between the time of the motion and the time at which the sentence was originally imposed. These circumstances can be an inmate’s deterioration in health, a family emergency necessitating an inmate’s caretaking and/or income-earning, or, as here, the emergence of a deadly pandemic to which an inmate is acutely susceptible. The USAO’s attempted policy of waiver or delay of these rights pre-sentencing is, as the Osorto court wisely recognized, “appallingly cruel,” id. *8, and akin to a deal with the devil:

It is no answer to say that Funez Osorto is striking a deal with the Government, and could reject this term if he wanted to, because that statement does not reflect the reality of the bargaining table. … As to terms such as this one, plea agreements are contracts of adhesion. The Government offers the defendant a deal, and the defendant can take it or leave it. … If he leaves it, he does so at his peril. And the peril is real, because on the other side of the offer is the enormous power of the United States Attorney to investigate, to order arrests, to bring a case or to dismiss it, to recommend a sentence or the conditions of supervised release, and on and on. … Now imagine the choice the Government has put Funez Osorto to. All that power—and the all too immediate consequences of opposing it—weighed against the chance to request release in desperate and unknowable circumstances that may not come to pass. That Faustian choice is not really a choice at all for a man in the defendant’s shoes. But the Court has a choice, and it will not approve the bargain.

[Id. *9 (citations omitted).]

Sadly, there have been numerous examples of these sorts of plea agreements in the District of New Jersey, and at least some are even worse than Osorto’s, because they entail outright waiver of the right to apply for compassionate release and not just a 150-day delay in exercising it.

These waivers, not yet scrutinized by courts in the District of New Jersey, are yet another unconscionable abuse of prosecutorial choice, plainly evidencing motivations which are utterly at odds with the supposed aim of their offices, which is—not that they ought need be reminded—doing justice.

When Prosecutors Overcharge, Call a Federal Criminal Defense Lawyer

Justice means something other than overcharging defendants to obtain convictions wherever possible and advocating for overlong sentences that will do more harm than good—let alone doing so to differing degrees based upon something like skin color. And while abusive prosecutors share blame with legislatures, law enforcement, and at times even judges and defense attorneys, the women and men who wield the power of prosecution must remain circumspect of their options and the foreseeable impacts of their choices.

They must all remember the “sworn duty” to seek justice for all. If the prosecution in your case has “forgotten” this, we will fight tirelessly to hold them accountable. source