Time, Inc. v. Hill (1967) – 1st Amendment

In Time, Inc. v. Hill, 385 U.S. 374 (1967), the Supreme Court extended the actual malice standard of the libel decision in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964) to a false light invasion of privacy.

The Court’s decision provided guidance on how courts should handle the species of invasion of privacy claims — called false light — most similar to defamation claims. It also shed more light on how the Court would apply its landmark libel decision in New York Times v. Sullivan.

Court applied actual malice standard to false light claim

In New York Times, the Court held that a public official cannot recover damages in a libel action unless he or she can show the publisher or speaker made false statements with actual malice — that is, with knowledge the statements were false or with reckless disregard as to their truth. In Hill, the Court applied the same standard to “false light” privacy cases.

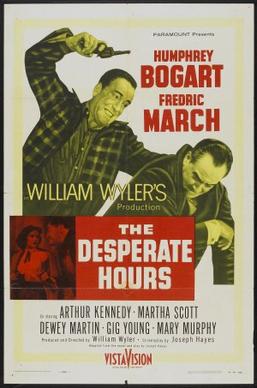

The lawsuit in Hill arose from an article in the February 1955 issue of Life Magazine. In the article, the author reviewed “Desperate Hours,” a Broadway play loosely based on a 1952 hostage standoff in Whitemarsh, Pennsylvania.

Broadway play review suggested hostages had been roughed up

The standoff began when three escaped convicts entered the home of James Hill and his wife and five children. The convicts held the family hostage for nineteen hours before releasing them unharmed.

In a news interview after his release, Hill stressed that the convicts had treated his family courteously, had not harmed them, and had not been violent in any way.

The article, however, included photos from the play and captions suggesting a son had been “roughed up” by the convicts, a daughter had bitten one of the convict’s hands to make him drop a gun, and Hill had thrown a gun through a door after the convicts foiled an escape attempt.

Hill sued, not because the article and photos damaged his reputation but because he believed Life had portrayed the event falsely so as to generate financial gain. A trial court ultimately awarded Hill $30,000, a verdict the New York Court of Appeals affirmed.

Court said punishing publishers for unintentionally false statements would burden First Amendment press freedom

In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court reversed the lower courts’ rulings.

Writing for the majority, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. held that because falsity is a key element in false light cases, publishers who unintentionally make false statements in these cases are entitled to the same protections as publishers who unintentionally libel public figures.

“We create a grave risk of serious impairment of the indispensable service of a free press in a free society if we saddle the press with the impossible burden of verifying to a certainty the facts associated in news articles with a person’s name, picture or portrait, especially when the content of the speech itself affords no warning of prospective harm to another through falsity,” Brennan wrote.

Central to the Court’s ruling was Brennan’s view that a price of freedom was the risk of being portrayed in a false light. “The risk of exposure is an essential incident of life in a society which places a primary value on freedom of speech and of press,” Brennan wrote.

Justices Potter Stewart and Byron R. White joined Brennan’s opinion. Justices Hugo L. Black and William O. Douglas concurred but maintained that the First Amendment entitled the press to greater freedom than the Court’s decision allowed.

Justice John Marshall Harlan II concurred in part and dissented in part, saying he believed negligence, not actual malice, was the appropriate standard for liability.

Dissenters thought negligence was appropriate standard

Chief Justice Earl Warren and Justices Abe Fortas and Tom C. Clark dissented, agreeing with Harlan that negligence was the appropriate standard and saying they believed Hill had proved negligence at trial.

This article was originally published in 2009. Douglas E. Lee is a circuit judge for the 15th judicial circuit in northwest Illinois. When he wrote this article, he was a partner with a law firm in Dixon, Illinois. Before joining that firm, he worked at Baker & Hostetler in Washington, D.C., where he focused his practice in First Amendment litigation. When he took the bench in 2019, Mr. Lee had considerable experience in matters involving libel, privacy, and access to the courts. He also wrote regular commentaries for the website of the First Amendment Center in Nashville.

By Douglas E. Lee cited https://mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/580/time-inc-v-hill