We found 85,000 cops who’ve been investigated for misconduct. Now you can read their records.

At least 85,000 law enforcement officers across the USA have been investigated or disciplined for misconduct over the past decade, an investigation by USA TODAY Network found.

Officers have beaten members of the public, planted evidence and used their badges to harass women. They have lied, stolen, dealt drugs, driven drunk and abused their spouses.

Despite their role as public servants, the men and women who swear an oath to keep communities safe can generally avoid public scrutiny for their misdeeds.

The records of their misconduct are filed away, rarely seen by anyone outside their departments. Police unions and their political allies have worked to put special protections in place ensuring some records are shielded from public view, or even destroyed.

Reporters from USA TODAY, its affiliated newsrooms across the country and the nonprofit Invisible Institute in Chicago spent more than a year creating the biggest collection of police misconduct records.

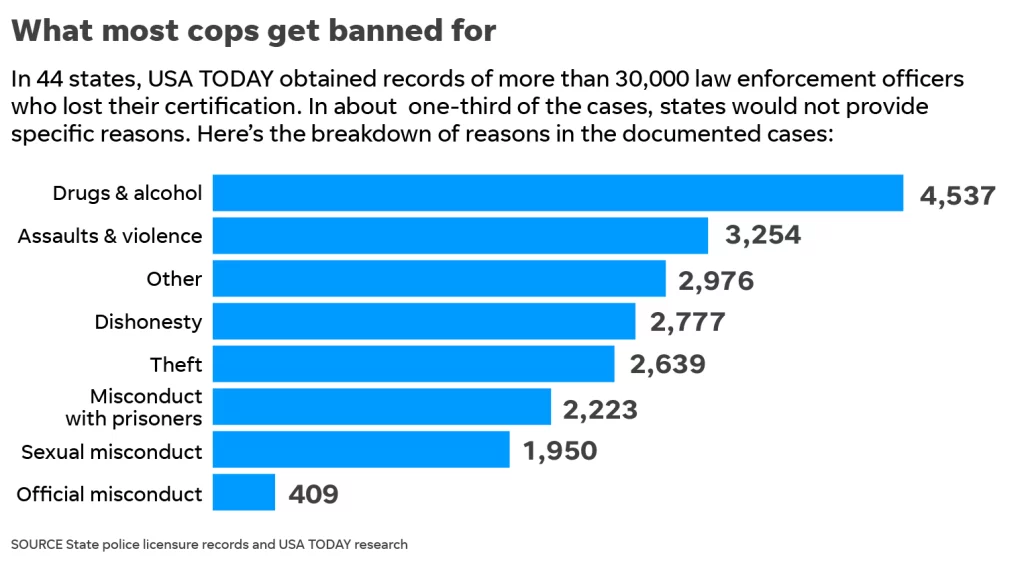

Obtained from thousands of state agencies, prosecutors, police departments and sheriffs, the records detail at least 200,000 incidents of alleged misconduct, much of it previously unreported. The records obtained include more than 110,000 internal affairs investigations by hundreds of individual departments and more than 30,000 officers who were decertified by 44 state oversight agencies.

- Most misconduct involves routine infractions, but the records reveal tens of thousands of cases of serious misconduct and abuse. They include 22,924 investigations of officers using excessive force, 3,145 allegations of rape, child molestation and other sexual misconduct and 2,307 cases of domestic violence by officers.

- Dishonesty is a frequent problem. The records document at least 2,227 instances of perjury, tampering with evidence or witnesses or falsifying reports. There were 418 reports of officers obstructing investigations, most often when they or someone they knew were targets.

- Less than 10% of officers in most police forces get investigated for misconduct. Yet some officers are consistently under investigation. Nearly 2,500 have been investigated on 10 or more charges. Twenty faced 100 or more allegations yet kept their badge for years.

The level of oversight varies widely from state to state. Georgia and Florida decertified thousands of police officers for everything from crimes to questions about their fitness to serve; other states banned almost none.

Search the database: Exclusive USA TODAY list of decertified officers and their records

Tarnished Brass: Fired for a felony, again for perjury. Meet the new police chief.

That includes Maryland, home to the Baltimore Police Department, which regularly has been in the news for criminal behavior by police. Over nearly a decade, Maryland revoked the certifications of just four officers. In Minneapolis, where officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on the neck of George Floyd until he died, at least seven police officers have been decertified since 2009, according to state records.

Floyd’s death sparked mass protests across the U.S. and around the world with millions of people calling for accountability for violent officers and the departments that allow them to retain their badge. It “was not just a tragedy, it was a crime,” said The Rev. Al Sharpton, delivering the eulogy at Floyd’s funeral on June 9.

“Until the law is upheld and people know they will go to jail,” Sharpton said, “they’re going to keep doing it, because they’re protected by wickedness in high places.”

We’re making those records public

The records USA TODAY and its partners gathered include tens of thousands of internal investigations, lawsuit settlements and secret separation deals dating back to the 1960s.

They include names of at least 5,000 police officers whose credibility as witnesses has been called into question. These officers have been placed on Brady lists, created to track officers whose actions must be disclosed to defendants if their testimony is relied upon to prosecute someone.

In 2019, USA TODAY published many of those records to give the public an opportunity to examine their police department and the broader issue of police misconduct, as well as to help identify decertified officers who continue to work in law enforcement.

Seth Stoughton, who worked as a police officer for five years and teaches law at the University of South Carolina, said expanding public access to those kinds of records is critical to keep good cops employed and bad cops unemployed.

“No one is in a position to assess whether an officer candidate can do the job well and the way that we expect the job to be done better than the officer’s former employer,” Stoughton said.

“Officers are public servants. They police in our name,” he said. There is a “strong public interest in identifying how officers are using their public authority.”

Dan Hils, president of the Cincinnati Police Department’s branch of the Fraternal Order of Policemen union, said people should consider there are more than 750,000 law enforcement officers in the country when looking at individual misconduct data.

“The scrutiny is way tighter on police officers than most folks, and that’s why sometimes you see high numbers of misconduct cases,” Hils said. “But I believe that policemen tend to be more honest and more trustworthy than the average citizen.”

Hils said he has no issue with USA TODAY publishing public records of conduct, saying it is the news media’s “right and responsibility to investigate police and the authority of government. You’re supposed to be a watchdog.”

The bulk of the records USA TODAY has published are logs of about 30,000 people banned from the profession by state regulators.

For years, a private police organization has assembled such a list from more than 40 states and encourages police agencies to screen new hires. The list is kept secret from anyone outside law enforcement.

On June 5, Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Oregon) announced legislation that would institute a number of reforms, including the creation of the first national, publicly searchable database of law enforcement officers who have engaged in inappropriate use of force or discrimination.

USA TODAY obtained the names of banned officers from 44 states by filing requests under open records laws.

The information includes the officers’ names, the department they worked for when the state revoked their certification and – in most cases – the reasons why.

The list is incomplete because of the absence of records from states such as California, which has the largest number of law enforcement officers in the USA.

Bringing important facts to policing debate

USA TODAY’s collection of police misconduct records began in 2016amid a nationwide debate over law enforcement tactics, including concern that some officers or agencies unfairly were targetting minorities.

A series of killings of black people by police in Ferguson, Missouri, Baltimore, Chicago, Sacramento, California, and elsewhere had sparked protests and renewed anger about police targeting minorities and needlessly using force to subdue them.

The Trump administration backed away from more than a decade of Justice Department investigations and court actions against police departments it determined were deeply biased or corrupt. In 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions said the Justice Department would leave policing the police to local authorities, saying federal investigations hurt crime fighting.

Laurie Robinson, co-chair of the 2014 White House Task Force on 21st Century Policing, said transparency about police conduct is critical to trust between police and residents.

“It’s about the people who you have hired to protect you,” she said. “Traditionally, we would say for sure that policing has not been a transparent entity in the U.S. Transparency is just a very key step along the way to repairing our relationships.”

In the late 1980s, Gary Cunningham, then-deputy director of the Minneapolis civil rights department, helped create a civilian review panel that investigated police misconduct and had the authority to compel officer testimony and recommend discipline. But the police union, he said, managed to lobby the state legislature to strip the panel of its subpoena power, which resulted in many officers refusing to testify and avoiding sanctions.

Today, the panel is a “paper tiger” organization, Cunningham said. A tiny fraction of cases result in discipline, and an even smaller fraction are available for public inspection.

Chauvin, for instance, racked up 17 misconduct complaints before Floyd. Only one resulted in discipline — in the form of two letters of reprimand. The city’s online database of misconduct complaints offers no details about the underlying allegations.

“If you make a joke out of the process, it doesn’t work very well,” said Cunningham, now president and CEO of Prosperity Now, a research and policy nonprofit in Washington, D.C. “The way we’ve been doing this has enabled and abetted the police brutality in our communities because once it’s not transparent, it’s hard to hold anybody accountable.” source

Help us investigate

The number of police agencies and officers in the USA is so large that the blind spots are vast. We need your help.