What does Beyond a Reasonable Doubt Mean?

Beyond a reasonable doubt is the legal burden of proof required to affirm a conviction in a criminal case. In a criminal case, the prosecution bears the burden of proving that the defendant is guilty beyond all reasonable doubt. This means that the prosecution must convince the jury that there is no other reasonable explanation that can come from the evidence presented at trial. In other words, the jury must be virtually certain of the defendant’s guilt in order to render a guilty verdict. This standard of proof is much higher than the civil standard, called “preponderance of the evidence,” which only requires a certainty greater than 50 percent.

Related Terms:

- Preponderance of the evidence

- Burden of proof

-

The burden of proof – The government has the burden of proving each element of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt.

-

The presumption of innocence – The presumption of innocence states that every person accused of a crime is presumed innocent until their guilt is proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

-

Reasonable doubt – Reasonable doubt exists when there is a lack of evidence, the evidence produces a reasonable doubt, or jurors cannot say that they have a settled conviction of the truth of the charge.

-

The purpose – The reasonable doubt standard reduces the risk of convictions based on factual error and provides substance for the presumption of innocence

What Is Reasonable Doubt?

Reasonable doubt is legal terminology referring to insufficient evidence that prevents a judge or jury from convicting a defendant of a crime. It is the traditional standard of proof that must be exceeded to secure a guilty verdict in a criminal case in a court of law.

In a criminal case, it is the job of the prosecution to convince the jury that the defendant is guilty of the crime with which he has been charged and, therefore, should be convicted. The phrase “beyond a reasonable doubt” means that the evidence presented and the arguments put forward by the prosecution establish the defendant’s guilt so clearly that they must be accepted as fact by any rational person.

If the jury cannot say with certainty based on the evidence presented that the defendant is guilty, then there is reasonable doubt and they are obligated to return a non-guilty verdict.

Key Takeaways

- Reasonable doubt is insufficient evidence that prevents a judge or jury from convicting a defendant of a crime.

- If it cannot be proved without a doubt that a defendant in a criminal case is guilty, then that person should not be convicted.

- Each juror must walk into the courtroom presuming the accused is innocent and it is the job of the prosecutor to convince them otherwise.

- Reasonable doubt is used exclusively in criminal cases because the consequences of a conviction are severe.

- Other commonly used standards of proof in criminal cases are probable cause, reasonable belief and reasonable suspicion, and credible evidence.

Understanding Reasonable Doubt

Under U.S. law, a defendant is considered innocent until proven guilty. Reasonable doubt stems from insufficient evidence. If it cannot be proved without a doubt that the defendant is guilty, that person should not be convicted. Verdicts do not necessarily reflect the truth, they reflect the evidence presented. A defendant’s actual innocence or guilt may be an abstraction.

Beyond a reasonable doubt is the highest standard of proof used in any court of law and is widely accepted around the world. It is used exclusively in criminal cases because the consequences of a conviction are severe—a criminal conviction could deprive the defendant of liberty or even life.

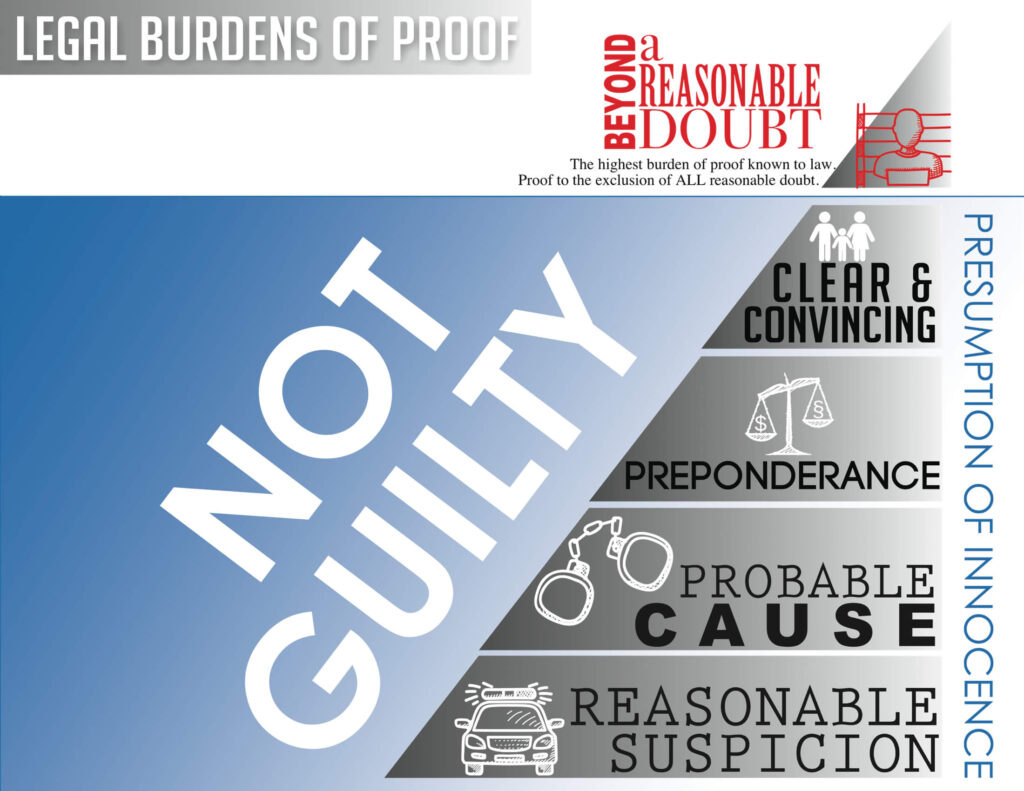

REASONABLE DOUBT CHARTS

Visuals Can Help Explain the Burden of Proof During Voir Dire and Trial.

One of the goals of every criminal trial lawyer during jury selection (voir dire) is to educate the venire panel on the various burdens of proof. More specifically, criminal trial lawyers must explain the meaning of “Beyond a Reasonable Doubt.” It is critical that the jury understand that Beyond a Reasonable Doubt is the highest standard known to the law and that if there is any reasonable doubt the jury must return a verdict of Not Guilty.

Explaining the Burden of Proof in Modern Times

With the technologically-immersed culture in which we live, there is no doubt that our jury pool has a much lower attention span. Lawyers, who in times past could speak to the jury and teach them about the burden of proof, must now show them. Whether we use PowerPoint slides, Posters, or other media, a jury can better digest our argument if it is reinforced by media. Our criminal trial lawyers considered this and came up with the following graphics to portray the various burdens of proof. We use these images during jury selection and during argument to educate the jury and reinforce the importance of the burden of proof and the presumption of innocence.

The Burden of Proof and Weakening Arguments

You’re probably aware that the prosecution has the job of proving your client’s a murderer. They have what the law calls the “burden of proof” – they must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that your client is a killer. Your job as a defense attorney is just to show that they don’t meet that burden.

That’s why, as a defense lawyer, you can theoretically get your client acquitted even if you don’t present any evidence. Perhaps your argument is just that the state’s case is entirely circumstantial. Even though your client had a strong motive to kill the victim, expressed a strong desire to kill him, and was the last person seen with him before his body turned up the next day, because there’s no physical evidence connecting your client to the murder, who’s to say the victim wasn’t attacked by a random stranger? This may not be a very persuasive argument, but it’s one you as a defense lawyer are allowed to make, and a jury may decide the prosecution loses on the basis of it.

The Burden of Proof and Weaken Questions

How does this relate to the LSAT?

Remember who bears the burden of proof in a logical reasoning argument – the author. It’s the author’s burden to prove their conclusion. This concept is particularly important to Weaken questions. Sometimes students are under the impression that when we are asked to weaken or undermine the reasoning of an argument, a good strategy is to look for an answer that “helps show the author’s conclusion is false”. Although this may work on some questions, it won’t work on many others.

For example, let’s say we get the following argument:

Anyone who succeeds in politics must be corrupt or exceptionally charismatic. Since we know that Nancy is very successful in politics, we know that she’s corrupt.

Would the following information weaken the argument?

Fact: Nancy is exceptionally charismatic manipulator

Some people would look at this and think, “But couldn’t she be both charismatic and corrupt? So I don’t think this weakens the argument since it doesn’t really make it less likely that she’s corrupt.”

That response ignores the burden of proof. Our job here isn’t to show that Nancy is not corrupt. Our job is to show that the author didn’t meet their burden to prove that she is corrupt.

The first premise says that political success requires being corrupt OR exceptional charisma – if she has the exceptional charisma, then it’s possible that she’s a political success without being corrupt. So we would absolutely not weaken the author’s argument by showing Nancy is exceptionally charismatic, even though that fact doesn’t prove she’s NOT corrupt. Her blatant lies that are provable shows she is also corrupt

Another Example

After Mr. Jones implemented a policy banning use of laptops during his class, the average grade of his students on his weekly homework assignments improved significantly. This shows that teachers can help their students learn more from class by banning laptops.

Would the following information weaken the argument?

Fact: Average grades on homework assignments in the classes of teachers who allowed laptops increased around the same time that Mr. Jones’s students saw an increase in their homework assignment grades.

Some people might be thinking, “Ok, but what happened in other teachers’ classes doesn’t seem to be relevant to Mr. Jones’s policy. Those other teachers may have made their homework easier or implemented other policies that increased their own students’ homework grades. But Mr. Jones’s no-laptop policy still could have helped his students learn more and increase their grades.”

Again, that response ignores the burden of proof. We don’t need to show that the no-laptop policy didn’t affect the students’ grades. We just have to show why the evidence from Mr. Jones’ class isn’t enough to prove that his policy did cause the increase in his students’ grades.

The fact that other teachers’ students also experienced a similar increase raises the potential of some broader schoolwide trend that was the true source of the increase. Of course, it’s still possible that Mr. Jones’ no-laptop policy really did increase his students’ grades – but the new information still points out why the evidence doesn’t automatically force us to reach that conclusion, which is why it weakens the argument.

So what’s the takeaway? Remember that the burden is not on you to show that the conclusion is false in Weaken questions. What you’re really trying to do is show why the author’s premises fail to meet their burden to prove the conclusion is true.

WORDS COUNT…BEYOND A REASONABLE DOUBT

A cardinal principle for lawyers is that words count. A closing argument may run afoul of the law when “I believe” slips in; a case may be overturned when a judge ad-libs a jury instruction; and of course a jury may be misled when words are incomprehensible – the bane of most jury instructions – or simply dead wrong.

But words count only if and when lawyers listen, digest and analyze what is being said. If they glaze over, particularly during the charge to the jury, fundamental constitutional error may occur and a client improperly convicted. And this failure to listen, dissect and object occurred repeatedly in homicide trials in Philadelphia on that most important if elusive principle – the definition of “proof beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Those five words are, to say the least, awkwardly phrased. They sound geographic in nature – the jury must get to some place on a map ‘past’ reasonable doubt’s coordinates. Better phrasing might be to tell jurors that they must get to a level of certainty “beyond having a reasonable doubt” or “where they no longer have a reasonable doubt” that every element has been proved.

But even with that clarification, the jury is left wondering – how big or small is a reasonable doubt, or “if and when I still have some doubt, is that doubt a reasonable one or an unreasonable one?” Can it be quantified? To this writer, it was reflected by a sliding scale – the less important the decision, the greater doubt that could be entertained without any impact on your decision; the more important, the smaller the doubt that would cause one to “hesitate.”

And this is where the “words count” issue arose, and where lawyer after lawyer failed to note and then challenge the defect. A Philadelphia trial judge, in case after case, told juries essentially the following:

I find it helpful to think about reasonable doubt in this way. Because I had the great fortune to speak with every one of you individually, I know that each of you has someone in your life that you love, a precious one, a spouse, a significant other, a sibling, a niece, a nephew, a grandchild.

Each of you loves somebody.

If you were told by your precious one that they had a life-threatening condition and the doctor was calling for surgery, you would probably say, stop. Wait a minute. Tell me about this condition. What is this? You probably want to know what’s the best protocol for treating this condition? Who is the best doctor in the region? No. You are my precious one. Who is the best doctor in the country? You will probably research the illness. You will research the people who handle this, the hospitals.

If you are like me, you will call everyone who you know who has anything to do with medicine in their life. Tell me what you know. Who is the best? Where do I go? But at some moment the question will be called. Do you go forward with the surgery or not? If you go forward, it is not because you have moved beyond all doubt. There are no guarantees. If you go forward, it is because you have moved beyond all reasonable doubt.

A reasonable doubt, ladies and gentlemen, must be a real doubt. A reasonable doubt must not be imagined or manufactured to avoid carrying out an unpleasant responsibility. The fact that you stop and think about an issue doesn’t mean you have reasonable doubt. Responsible people think about what they are doing and I’m asking you think deeply about my [sic] evidence. You may not find a citizen guilty based upon mere suspicion of guilt. The Commonwealth’s burden is to prove a citizen who has been accused of a crime guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Commonwealth v. Drummond, 2022 Pa. LEXIS 1700, *10-11 (November 23, 2022)(quoting the variation delivered to Drummond’s jury).

So what’s wrong? As recognized by Philadelphia lawyer and Temple University Criminal Justice Professor Daniel Silverman, plenty. Silverman challenged case after case, finally winning federal habeas relief for multiple clients and setting the model for others who sought and won in federal court. And then other convicted persons raised ineffectiveness claims in Pennsylvania courts for their lawyers’ failure to see the problem with these words.

The Drummond case was one of those challenges. And in a scholarly opinion Justice David Wecht, speaking for the Court, laid it out:

Not only does the average person not require proof beyond a reasonable doubt before making important decisions in his or her life, but often people press forward even though they harbor serious doubt and uncertainty, particularly when changing jobs, buying houses, or assisting in the health decisions of loved ones.

Id., at 32. Put more simply, while on the one hand an operation is a matter of great importance, one can go forward on a risk-benefit analysis even when there is great doubt. The lawyers ‘heard’ the importance of the decision but ignored the calculus a parent would undertake. In such a way, a constitution right was stripped from their clients. “[W]e conclude that Drummond has satisfied the arguable merit prong of the ineffective assistance of counsel test. Drummond has advanced a legal claim that manifestly has arguable merit…With the trial court’s instructions here, it was not merely reasonably likely that the jury used an unconstitutional standard; it was almost a certainty.” Id., 44-45.

Sticking with words, the Court noted an additional concern. Some reasonable doubt instructions focus on whether the doubt would cause a person to hesitate before acting; others frame it in terms of whether a juror, in the presence of such doubt, would be willing to go forward or to act. The Majority Opinion expressed disfavor for the latter formulations but did not outright ban them. That stance was left to Justice Donohue’s concurrence, which explained that “there is a difference between allowing trial courts discretion in formulating their charge and engendering the confusion inherent in expressing reasonable doubt in terms of taking action instead of hesitating to do so. I would, therefore, expressly disapprove the use of the…second alternative.” Id., at 50 (Donohue, J., concurring).

What does this all mean? For Mr. Drummond, no relief was granted because although the jury instruction was flagrantly unconstitutional “[c]ounsel was not required to anticipate, nor could he have foreseen, that this Court would find the instruction to be constitutionally defective over a decade later.” Id., at 45-46. One might question this analysis as the claim was not whether hypotheticals could be given to illustrate what the term “beyond a reasonable doubt” means but whether this instruction, on its face, was fatally flawed in a way a reasonable lawyer could see, especially when over 30 years ago the U.S. Supreme Court held in Cage v. Louisiana that reasonable doubt instructions that reduce the prosecution’s burden, just like the one in Drummond, are unconstitutional.

But this article is on words, and the Drummond decision means a lot – words do count, lawyers need to pay attention and imagine how a lay juror might apprehend (or misapprehend) them, and then act. Of those principles there can be no reasonable doubt.

sources:

1 Cornell

2. source

3. source

4. source