“The Blackfeet, The Great Northern Railway, and Glacier National Park”

According to their oral history, the people of the Blackfoot Confederacy have lived in what is now known as Montana for ten thousand years. Their original reservation was established by the Lame Bull Treaty in 1855. In 1895, the Blackfeet negotiated an agreement with the United States government to sell 800,000 acres of mountainous land on the western border of the reservation for the sum of 1.5 million dollars. The Federal government acquired the land for the purpose of mineral exploration. This agreement also stipulated that the Blackfeet would retain the right to hunt, fish, and gather wood on this land so long as it remained publicly owned. After several years of advocacy, most notably by Louis B. Hill, president of the Great Northern Railroad, Glacier National Park was created by an act of Congress in 1911. The portion of the former Blackfeet Reservation sold to the Federal government in 1895 became part of the newly established Glacier National Park. With this transfer, the people of the Blackfeet Nation lost their access to this land they had used for generations.

government to sell 800,000 acres of mountainous land on the western border of the reservation for the sum of 1.5 million dollars. The Federal government acquired the land for the purpose of mineral exploration. This agreement also stipulated that the Blackfeet would retain the right to hunt, fish, and gather wood on this land so long as it remained publicly owned. After several years of advocacy, most notably by Louis B. Hill, president of the Great Northern Railroad, Glacier National Park was created by an act of Congress in 1911. The portion of the former Blackfeet Reservation sold to the Federal government in 1895 became part of the newly established Glacier National Park. With this transfer, the people of the Blackfeet Nation lost their access to this land they had used for generations.

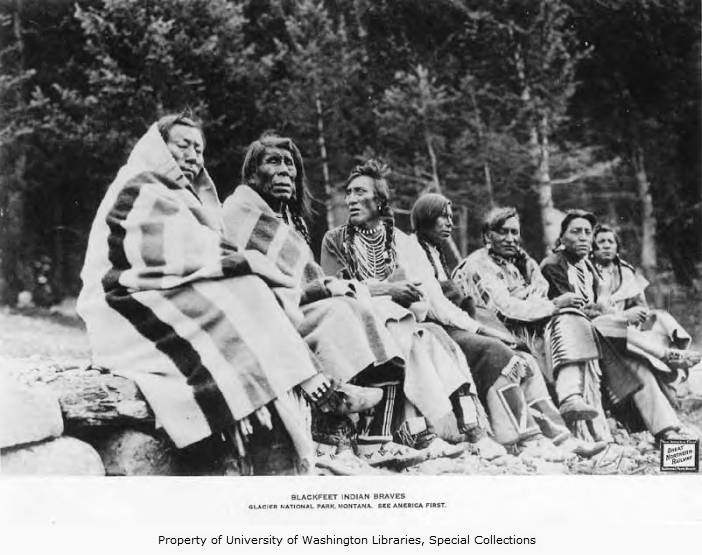

This film, produced by Quinn Smith (Chickasaw) for the IACB, explores the history of the Blackfeet people in early twentieth century, particularly in relation to the creation of Glacier National Park. The historic photos used in this film come from the collection of the Museum of the Plains Indian in Browning, Montana. Many of these images were collected from various sources by Ralph Reiner of Billings, Montana, as part of his research for an unpublished manuscript The Blackfeet of Montana. Ernie Heavy Runner and Darrell Norman, both respected Blackfeet elders, narrate the film and share their knowledge of these events and people. These images and the oral histories shared by Mr. Heavy Runner and Mr. Norman, present a unique perspective on this era from a Native American viewpoint.

Glacier National Park, The Great Northern Railway and the Blackfeet Portraits of Winold Reiss.

Glacier National Park, The Great Northern Railway and the Blackfeet Portraits of Winold Reiss.

In this year of 2010, Glacier National Park is celebrating 100 years as a national treasure. The Park, which straddles the Montana Canadian border in Northwest Montana, is one of the most remote of all parks in the National Park system. If it was not for the effort of railroad giant, James Hill, who pushed legislation through the U.S. Congress establishing Glacier 1910, this scenic wonderland of the Northwest may not have been preserved for future generations.

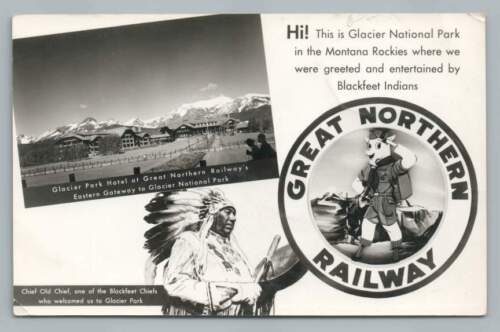

James Hill envisioned a “Playground of the Northwest” that would attract people and their money from all over the world, moneyed people who traditionally traveled and enjoyed the sights and attractions of Europe. To interest visitors to Glacier, Hill, with the help of his son, Louis, embarked on an ambitious building spree, where they built a chain of hotels, chalets, boats, roads, and trails in the mountains of Glacier and created the banner, “See America First,” in order to entice visitors to the Rocky Mountain Northwest.

The motive behind all this activity was to promote travel on Hill’s Great Northern Railway.

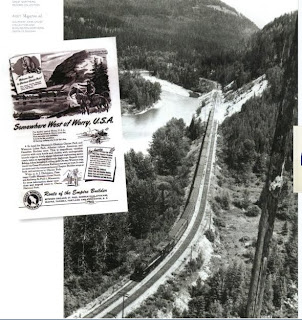

James Hill was one of several “captains” of the railroad industry in the United States, who made a fortune from investment in the transportation of goods and people on railways that linked America from coast to coast after the Civil War. In 1893, Hill’s Great Northern Railway connected the Upper Mississippi River Valley to Puget Sound.

James Hill was one of several “captains” of the railroad industry in the United States, who made a fortune from investment in the transportation of goods and people on railways that linked America from coast to coast after the Civil War. In 1893, Hill’s Great Northern Railway connected the Upper Mississippi River Valley to Puget Sound.

Great Northern RouteAll along the route from Minneapolis to the Pacific, Hill promoted the Northwest as a wonderland of natural beauty; a land that still possessed many of the desirable attributes inherent in the American frontier. Hill also cashed in on the growing popularity of what historians in the twentieth century describe as the mythic West; a perception of the West in the American mind, where the exploits of cowboys, frontier army and Indians denoted adventure and unbridled heroism. The Native Americans, in particular, were of interest because of their role in promoting the “Wild West” with their performances in Buffalo Bill Cody’s wild west shows, which toured the United States and Europe between 1883 and 1917. At every stop along the tour, Native Americans in the show helped to recreate the Indian wars of the plains, audiences loved the excitement of western America. In the early twentieth century, The Great Northern helped to keep this romantic image of Native Americans alive by promoting the Blackfeet Nation, whose reservation extended along the eastern boundaries of the park; a trip to Glacier brought visitors in close proximity to the Blackfeet and their culture.

Blackfeet Indian Reservation

Traditionally the Blackfeet nation consists of three different tribes with the same language and customs; the Pecunnies (Piegans), the Bloods, and the Blackfeet. Before moving onto the Plains, and adapting a nomadic culture centered on the buffalo, the Blackfeet lived around the “forest near Lesser Slave Lake. Incessant war forced upon them by the powerful Chippewas pushed them steadily southward until they reached the wide plains bordering the Rocky mountains in what is now Montana.”[Frank Bird Linderman] The Blackfeet eventually occupied a region that ran north to south from Saskatchewan to the Yellowstone. Early Plains settlers and frontier military viewed the Blackfeet as a warrior society, who resisted white settlement in their region. At the end of the Plains Indian wars in the 1870s, the federal government moved the Blackfeet to land reserved for them east of what became Glacier National Park.

Blackfeet 1914

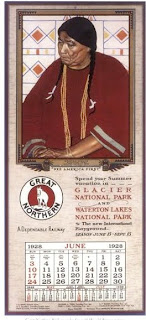

Once on reservations, the Blackfeet, along with other Native America Tribes, occupied the interest of anthropologist, writers and artists; many flocked to the American West in order to record what they believed were the last vestiges of Native America life. James Hill understood the draw that the Blackfeet would have as a “tourists attraction,” the search was on for an artists, who had a close association with the Blackfeet, and who could capture in Blackfeet portraits the colorful character of the people. The Great Northern Railway found such an artist in Winold Reiss.

The Blackfeet gave Winold Reiss the name Beaver Child when they inducted him into the tribe in the winter of 1919.

Reiss was born in Karlsruhe, Germany, the Black Forest region. He gained appreciation for cultural differences among people from his father, a German artist who focused his art in peasant cultures of the Black Forest. Both father and son trained at the Royal Academy in Munich. Winold was fascinated with the Indians of North American, a fascination fueled by the novels of James Fenimore Cooper. In 1913, Winold Reiss traveled to American to study the North American Indians. Reiss believed that he could use his art to break down racial barriers by picturing the honor, beauty, and dignity of all peoples. His bold style, coupled with his attention to detail of racial characteristics and cultural customs, made his Blackfeet portraits unique. In the summer of 1943, Reiss once again stayed with the Blackfeet, finishing 75 portraits. Many of these portraits appeared on Great Northern Railway calendars

and were included in a portfolio sold by the Great Northern Railway to promote Glacier National Park and rail travel to Blackfeet country in the 1940s.

and were included in a portfolio sold by the Great Northern Railway to promote Glacier National Park and rail travel to Blackfeet country in the 1940s.

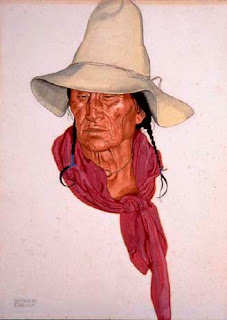

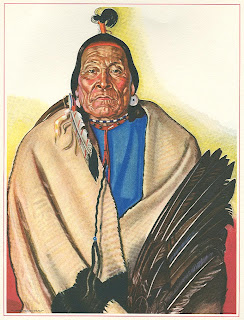

Portraits of the Blackfeet people by Winold Reiss:

Jim Blood, an old Pecunnie brave

Only Child, Pecunnie girl sitting against a tepee back-rest made of thin willow sticks

Plume, a modern representation of the Kainahs–proud owner of many lodges, horses and a large heard of cattle.

Short Man, A fine old warrior of the Pecunnies who lived until his eight-sixth year. He was an expert sign talker.

Big Face Chief, A stalwart member of the north Pecunnie band of Blackfeet. His necklace and eagle wing fan mark him as a Medicine Man.)