Free Speech, the First Amendment, and Social Media

by John Bandler

- NOTE: This is my original article after the events of 1/6/2021 and is not updated regularly and does not have the newer diagrams. So go read this article here which does not directly refer to those events and is updated more frequently.

Here’s a quick primer on the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, what it means for free speech, and how it applies to social media and other platforms for speech. Misconceptions exist because law can be confusing and some people disseminate inaccurate information. This short piece lays out the basics and ties it into the events of 1/6/2021.

The U.S. Constitution

The United States Constitution is the foundation of all laws in this country. It establishes our system of government and puts limits upon what government can do. It created a system of checks and balances by establishing three branches of government — executive, legislative, and judicial. Our federal government is of limited powers (in theory), and any powers not specifically granted to it are reserved for the states and individuals. The Constitution does not say what private individuals and organizations can or cannot do (though other laws do).

The First Amendment

Within the U.S. Constitution are Amendments, and the first ten are known as the Bill of Rights. These grant rights and freedoms to the people and restrict what the federal government can do. These restrictions have also been applied to state and local governments. Relevant here is the First Amendment, which reads:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Of course this “freedom of speech” protection extends past the spoken word to other forms of expression, and includes writings, art, and more.

In the centuries since the First Amendment was enacted, courts have weighed in many times about what it means, and legal evolution progressed. Thousands of people have been criminally prosecuted or civilly sued after they said or wrote something, and then they raised a First Amendment defense. Judges made rulings, these rulings were appealed, and then other judges ruled. Occasionally, the U.S. Supreme Court (our country’s highest court) ruled. We now have a significant body of law and analysis — thousands of pages — interpreting those forty five words of the First Amendment.

The law is clear that the government must not violate the First Amendment, nor can the government be a tool to impinge upon rights guaranteed by it. This has implications for criminal and civil proceedings. In criminal proceedings, the full weight of government seeks to punish an individual. In civil proceedings, which are often between private parties, it is government that runs the courts which resolve these disputes.

Three categories of speech

It is helpful to think how particular speech might fall into one of three categories regarding what government can and cannot do:

- Fully protected free speech, from which no successful legal action (criminal or civil) can be brought,

- Speech that might be civilly actionable (e.g., subject to a successful civil suit for defamation, or invasion of privacy, infliction of emotional distress, etc.),

- Speech that might be criminally actionable (subject to a successful criminal prosecution, such as harassment, stalking, menacing, or part of another crime).

Note that these categories are about what government can (or cannot) do. Separate from this are private consequences — what a private party might think or do as a result of what we say. Our speech can always have private consequences, and that falls outside of the First Amendment.

The line between these three categories can be blurry. Any government restrictions upon speech must be “narrowly tailored” and “content neutral” to avoid violating the First Amendment, and not all speech is protected by the First Amendment.

Here are some examples of speech that might be the proper subject of a criminal prosecution:

- Menacingly stating “Give me your wallet or I’ll kill you”.

- Falsely shouting “Fire!” or “Bomb!” in a crowded theatre causing panic and injury.

- Saying words that incite violence or a riot (or perhaps even the storming of the U.S. Capitol).

Civil lawsuits involving speech also face First Amendment scrutiny. A lawsuit (civil action) for defamation (libel or slander) will fail if the speech is true. Public figures face an additional hurdle because they must also show actual malice—that the writer knew the statement was false, or recklessly disregarded whether it might be false. Other civil lawsuits could include for invasion of privacy, depicting someone in a false light, or intentional infliction of emotional distress.

Thus the First Amendment is a limitation on how government can restrict speech. It provides freedoms (from government) to private individuals and entities about what they can say, or choose not to say.

Again, it would be a mistake to say that the First Amendment is a restriction upon what individuals or private organizations can do. And yet it seems that many individuals make this mistake—including some who know better.

Senator Hawley’s book deal

Josh Hawley is a United States Senator from Missouri, a Yale educated lawyer, former state attorney general and law professor. Despite these impressive bona fides, he falsely claimed (shortly after the riotous events of 1/6/2021) that the cancelation of his book contract by Simon & Schuster was a violation of the First Amendment.

He was wrong, because the publisher is a private company, protected by the First Amendment not restricted by it. The publisher has a choice whether to print or not. It is nonsensical to argue that the First Amendment obligates a private company to do a Senator’s bidding. Senator Hawley remained free to find another publisher or self publish his book (he did indeed find another publisher for his book), and any legal claim he might have against Simon & Schuster would need to be grounded in contract law, not constitutional law. His legal claim would likely fail, because chances are good that under the book contract Simon & Schuster had ample cause to cancel publication.

Sen. Hawley surely knew the law around free speech better than he stated. And it is supremely ironic for a government official to claim that a private entity violated their First Amendment right. As a side note, we can evaluate the general credibility of a person when we identify instances where they knowingly tell an untruth. By debunking Sen. Hawley’s smaller untruth about the First Amendment, we can better evaluate his credibility for more serious lies about conspiracy theories and election fraud. A reckless disregard for the truth is evident.

Former president Trump’s social media accounts

On January 8th 2021, Twitter suspended the account of then soon-to-be former president Donald Trump, citing violation of their rules. Facebook did the same.

Some mistakenly claimed this also constituted a First Amendment violation, but that cannot be. Like Simon & Schuster, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media companies are not government actors, but private entities. The First Amendment exists as a shield to protect private entities from government restrictions on speech. In no way could the First Amendment restrict private entities, or make private entities obligated to do a President’s bidding to allow or prohibit certain speech. Trump accepted Twitter’s Terms of Service (as all Twitter users have). Those terms are a contract, he was bound by them, violated them (repeatedly), and was banned according to it. It is not a First Amendment issue (though many other issues do exist).

Social media regulation?

If social media platforms are not restricted by the First Amendment as private entities, are they subject to other laws or regulations? Undoubtedly, but that’s getting more complex and beyond the scope here. But think of the growing field of privacy law (what the social media company can do with personal information about users) and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (47 U.S. Code § 230).

Social media platforms bring complicated issues. There is a tension between allowing anyone to say whatever they want, versus creating some rules and moderating the platform. Most would agree such platforms should take reasonable steps to reduce criminal activity, reduce incitement to violence, limit hate speech, and even reduce the spread of conspiracy theories, propaganda, and disinformation. Platforms without any moderations become cesspools of disgusting speech and overt criminality.

Once we agree upon some of the basics, we can have a reasonable debate about how moderation should be done. Conversely, if we cannot agree upon basic facts or basic legal principles, or if we apply them selectively depending on whose side we want to champion, we are not going to have a reasonable debate.

There are also concerns about how social media monetize their platform—how they collect, use, and share user information. Users don’t pay for Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn or any of the other social media platforms, but that doesn’t mean it is free. As the saying goes, “If the service is free, the product is you”. All of these platforms seek to make money based upon information about their users. This is the subject of a growing area of regulation and law, and we should increase our awareness of the privacy policies we agree to, our privacy settings, and the companies who use our information.

Consumers and voters remain the key

Consumers and voters need to exercise their own diligence to obtain facts, and be resistant to appeals to anger and hate, conspiracy theories, propaganda, and lies. Decisions should be made based on facts, logic, and reason. We should vote for candidates who are truthful, and not support those who lie or who are unethical. As consumers, we make decisions about what we buy, click on, or watch, and those decisions should be thoughtful too. You can read more of my thoughts on that here.

Conclusion

While I am a lawyer and I teach about law, I am no expert in First Amendment and Constitutional law. This short article is for your introductory information but is not tailored to your circumstances, nor is it legal advice. Hopefully it makes some foundational concepts clear, and puts you on the road to better understanding.

Free Speech, the First Amendment, and Social Media

First Amendment things to know

by John Bandler

Here’s a primer on the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, what it means for free speech, and how it applies to social media and other platforms for speech. Misconceptions exist because law can be confusing and some disseminate false information. This short piece lays out the basics without tying it too closely to individuals or political events.*

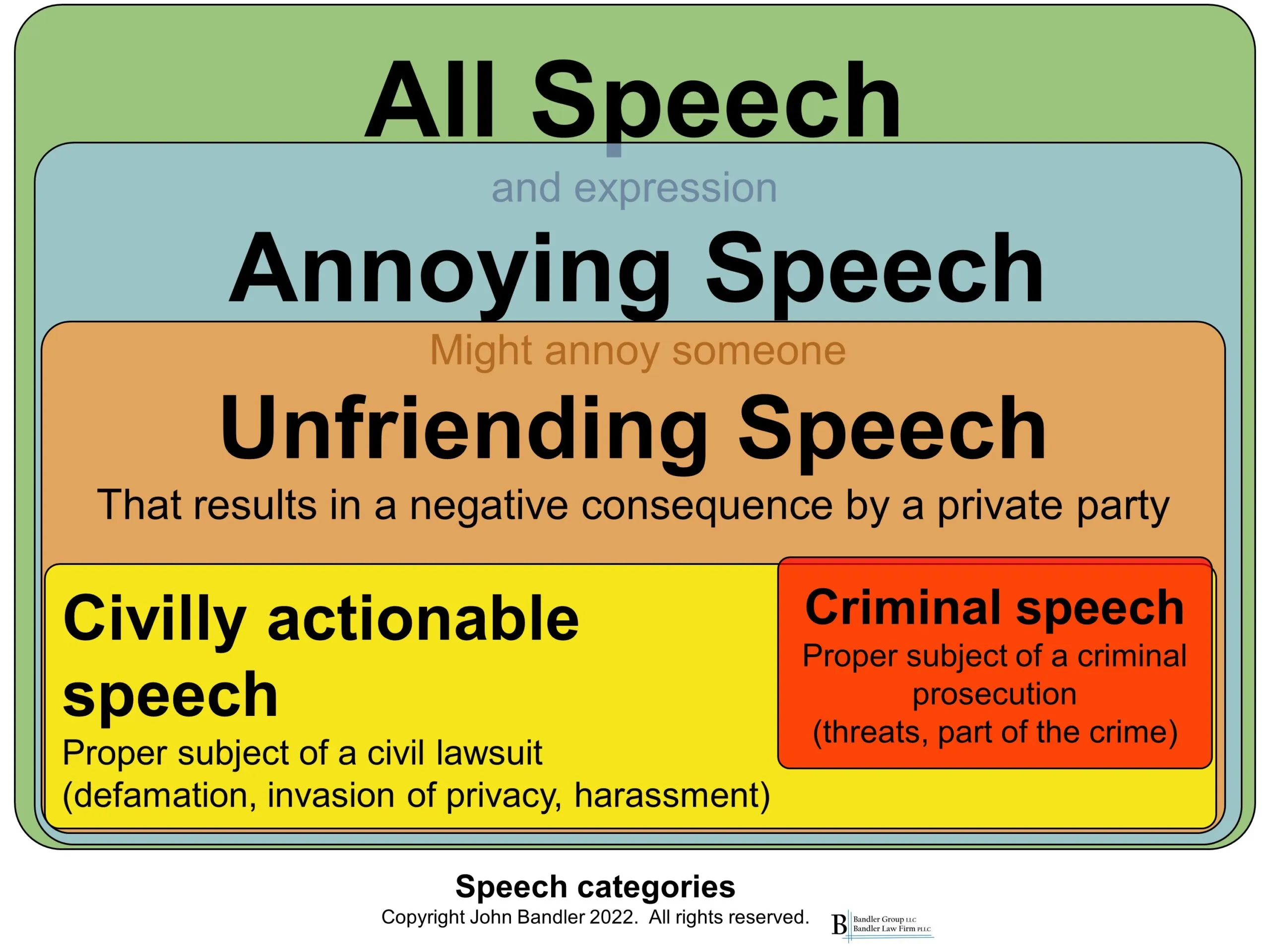

Before we get into the details, let’s outline a way to categorize speech, starting with the biggest category (everything) and then smaller and smaller subsets of that.

- All speech (any speech)

- Annoying speech (annoys at least one person)

- Unfriending speech (annoys a person enough that they take some type of action)

- Civilly actionable speech (a very small subset of the above)

- Criminally actionable speech (a tiny, infinitesimal subset of the above)

This diagram lays it out, though not to scale (see later as I adjust that).

The First Amendment limits the scope of those last two categories, by protecting us from those types of government actions, as we will dive into now.

The U.S. Constitution

The United States Constitution is the foundation of all laws in this country. It establishes our system of government and puts limits upon what government can do. It created a system of checks and balances by establishing three branches of government — executive, legislative, and judicial. Our federal government is of limited powers (in theory), and any powers not specifically granted to it are reserved for the states and individuals. The Constitution does not say what private individuals and organizations can or cannot do (though other laws do).

The First Amendment

Within the U.S. Constitution are Amendments, and the first ten are known as the Bill of Rights. These grant rights and freedoms to the people and restrict what the federal government can do. These restrictions have also been applied to state and local governments (via the Fourteenth Amendment). Relevant here is the First Amendment, which reads:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Of course this “freedom of speech” protection extends past the spoken word to other forms of expression, and includes writings, art, and more.

In the centuries since the First Amendment was enacted, courts have weighed in many times about what it means, and legal evolution progressed. Thousands of people have been criminally prosecuted or civilly sued after they said or wrote something, and then they raised a First Amendment defense. Judges made rulings, these rulings were appealed, and then other judges ruled. Occasionally, the U.S. Supreme Court (our country’s highest court) ruled. We now have a significant body of law and analysis — thousands of pages — interpreting those forty five words of the First Amendment.

The law is clear that the government must not violate the First Amendment, nor can the government be a tool to impinge upon rights guaranteed by it. This has implications for both criminal and civil proceedings. In criminal proceedings, the full weight of government seeks to punish an individual. In civil proceedings, which are often between private parties, it is government that runs the courts which resolve these disputes. The First Amendment still applies, though to a different degree.

Three categories of speech and government action

It is helpful to think how particular speech might fall into one of three categories regarding what government can and cannot do:

- Speech that might be criminally actionable (subject to a successful criminal prosecution, such as harassment, stalking, menacing, or part of another crime).

- Speech that might be civilly actionable (e.g., subject to a successful civil suit for defamation, or invasion of privacy, infliction of emotional distress, etc.),

- Fully protected free speech, from which no successful legal action (criminal or civil) can be brought,

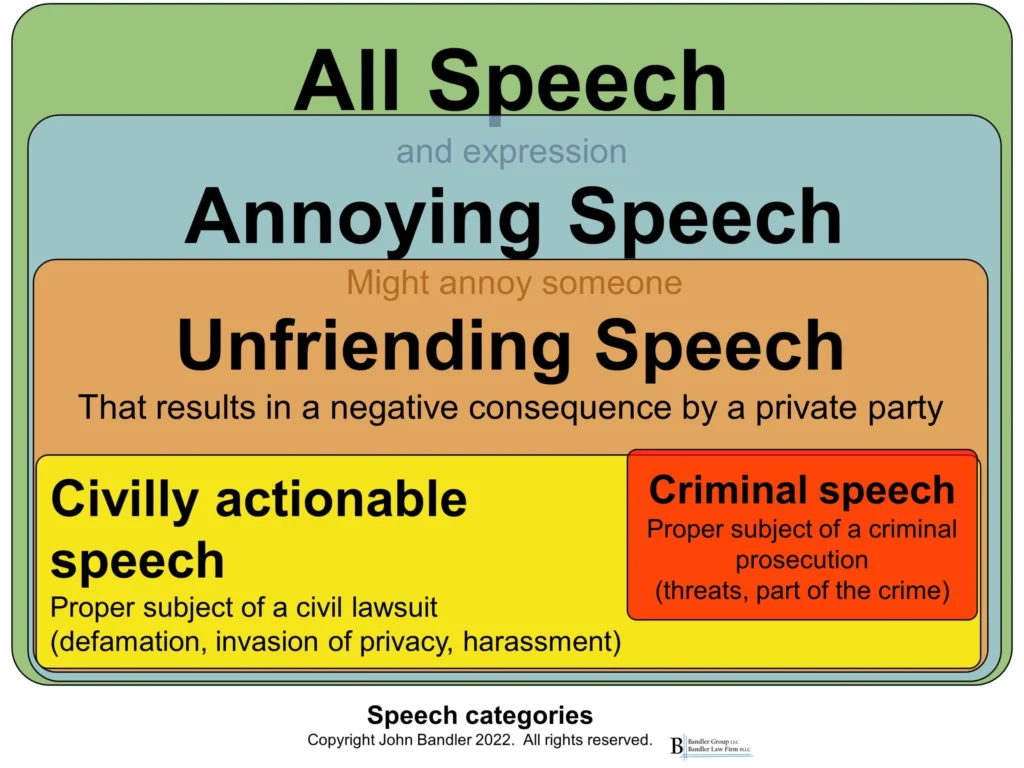

Note that these categories are about what government can (or cannot) do. Often (but not always) annoying and unfriending speech is protected from government consequences by the First Amendment. The diagram here lays this out roughly and we see how large portions of all speech, annoying speech, and unfriending speech are protected.

The line between these three categories can be blurry. Any government restrictions upon speech must be “narrowly tailored” and “content neutral” to avoid violating the First Amendment, and not all speech is protected by the First Amendment.

Separate from the question of government action are private consequences — what a private party might think or do as a result of what we say. Our speech can always have private consequences, and that falls outside of the First Amendment.

1. Potentially “criminal” speech

This is a very small category of speech. Here are some examples of speech that might be the proper subject of a criminal prosecution:

- Menacingly stating “Give me your wallet or I’ll kill you”.

- Other words that are part of a criminal act.

- Falsely shouting “Fire!” or “Bomb!” in a crowded theatre causing panic and injury.

- Saying words that incite violence or a riot.

2. Potentially civilly actionable speech

This is a small category, but larger than the prior. Civil lawsuits involving speech also face First Amendment scrutiny. A lawsuit (civil action) for defamation (libel or slander) will fail if the speech is true. Public figures face an additional hurdle because they must also show actual malice—that the writer knew the statement was false, or recklessly disregarded whether it might be false. Other civil lawsuits could include for invasion of privacy, depicting someone in a false light, or intentional infliction of emotional distress.

An example of potentially civilly actionable speech includes statements made by Alex Jones, for which he is being sued in multiple forums. Also, another potential example includes statements attacking the integrity of certain voting systems, which is also the subject of various lawsuits which claim these statements were false and defamatory.

3. Potentially “free speech” under the First Amendment

Most speech is protected free speech under the First Amendment, including expressions of opinion. By this we mean the government cannot impose any sanction for that speech, either in the criminal courts or civil courts.

Thus the First Amendment is a limitation on how government can restrict speech. It provides freedoms (from government) to private individuals and entities about what they can say, or choose not to say.

Again, it would be a mistake to say that the First Amendment is a restriction upon what individuals or private organizations can do. And yet it seems that many individuals make this mistake—including some who probably know better.

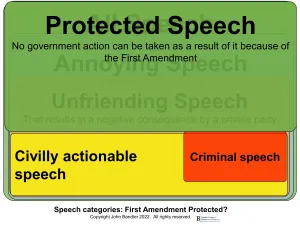

4. The prior diagrams were not to scale

The prior diagrams were not to scale at all, I wanted my text to be visible and show the general overlap.

Now it is worth emphasizing that the vast majority of speech is protected by the First Amendment. A small sliver could be subject to valid civil claims, and a really tiny piece could be criminally punished. Here I show it in a slightly better scale (still not perfect) and criminal speech is just a tiny dot.

All speech can have a private consequence

I mentioned this above and created this section just to make sure the point comes across.

Any speech or expression could have many consequences from private individuals and organizations, but this would not implicate The First Amendment. The First Amendment limits government interference with speech, it protects speech, and does not limit private reaction to that speech.

Private book deals can be cancelled based on one’s speech

Imagine a book deal an author has with a publisher. They have a contract, and the contract has many terms, and the publisher is a private company.

The author commits an act or says something that is inconsistent with the publisher’s values, or perhaps inconsistent with the publisher’s bottom line if they feel the books will not sell. The contract probably has a clause to address this (perhaps called a “morals clause”).

The publisher cancels the deal and the author claims a violation of their First Amendment rights.

The author is wrong, because the publisher is a private company, protected by the First Amendment not restricted by it. The publisher has a choice whether to print or not. The First Amendment does not obligate a private company to do someone else’s bidding.

Any legal claim against the publisher would need to be grounded in contract law, not constitutional law. And as indicated, it is probable the publisher inserted a clause in the contract allowing cancellation for certain circumstances.

If the author was also a government official, their claim of First Amendment violation would make even less sense. Since the First Amendment protects us from government interference, it would make no sense to claim it allows government officials to dictate what can or cannot be published.

Social media accounts can be suspended or terminated based on one’s speech

Users of social media such as Twitter and Facebook have complained that their First Amendment rights were violated following social media platform suspension or termination. Sometimes these users are government officials, even powerful ones.

Like a book publisher, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media companies are not government actors, but private entities. The First Amendment exists as a shield to protect private entities from government restrictions on speech. The First Amendment does not restrict private entities, or make private entities obligated to do certain things.

A claim of First Amendment violation is more ironic when it is a government official seeking to direct a private platform to allow or prohibit certain speech.

Platform users accept the Terms of Service and should abide by them. Most people agree that social media platforms should have some rules about what speech is acceptable, and what speech is not, and that there should be consequences for speech that falls outside of what is allowed.

These terms are a contract, and some users may be suspended or banned if they violate them.

It is not a First Amendment issue, though many other issues do exist. Hopefully we can have reasonable debate about (1) what the platform rules should be, and (2) how those rules should be enforced.

Social media regulation?

If social media platforms are not restricted by the First Amendment as private entities, are they subject to other laws or regulations? Undoubtedly, but that’s getting more complex and beyond the scope here. But think of the growing field of privacy law (what the social media company can do with personal information about users) and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (47 U.S. Code § 230).

Social media platforms bring complicated issues. There is a tension between allowing anyone to say whatever they want, versus creating some rules and moderating the platform. Most would agree such platforms should take reasonable steps to reduce criminal activity, reduce incitement to violence, limit hate speech, and even reduce the spread of conspiracy theories, propaganda, and disinformation. Platforms without any moderations become cesspools of disgusting speech and overt criminality.

Once we agree upon some of the basics, we can have a reasonable debate about how moderation should be done. Conversely, if we cannot agree upon basic facts or basic legal principles, or if we apply them selectively depending on whose side we want to champion, we are not going to have a reasonable debate.

There are also concerns about how social media monetize their platform—how they collect, use, and share user information. Users don’t pay for Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn or any of the other social media platforms, but that doesn’t mean it is free. As the saying goes, “If the service is free, the product is you”. All of these platforms seek to make money based upon information about their users. This is the subject of a growing area of regulation and law, and we should increase our awareness of the privacy policies we agree to, our privacy settings, and the companies who use our information.

Consumers and voters remain the key

Consumers and voters need to exercise their own diligence to obtain facts. Be resistant to anger and hate, conspiracy theories, propaganda and lies. Decisions should be made based on facts, logic, and reason. We should vote for candidates who are truthful, and not support those who lie or who are unethical. As consumers, we make decisions about what we buy, click, watch, or scroll. All of those decisions are monetized and should be thoughtful. You can read more of my thoughts on that here.

Conclusion

This short article is for your introductory information but is not tailored to your circumstances, nor is it legal advice. Hopefully it makes some foundational concepts clear, and puts you on the road to better understanding.

Books have been written about the First Amendment, some people specialize in it, as do some law courses. This does not pretend to be the last word, feel free to continue your research.

Additional reading

- First Amendment things to know

- Building Better Consumers and Voters My short article about what we need to do to get better at learning facts, putting aside disinformation, and making better choices about who leads our country.

- U.S. Constitution

- Students, Learning, and Teaching

- Communications Decency Act 47 U.S. Code § 230 – Protection for private blocking and screening of offensive material, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/47/230

- Cornell LII Wex on First Amendment, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/first_amendment

- I walk through the diagrams in the embedded video below (or find it on YouTube at https://youtu.be/Rl-QqR7lNsE)

- * The original version of this article tied First Amendment to the events of 1/6/2021 and remains here, but is not updated as frequently, lacks the diagrams, and I name names and include my opinion.

First Amendment Q&A

- What is the highest law in the U.S. regarding government’s restriction of speech and expression?

- The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution

- What does the First Amendment protect against?

- The First Amendment is a limit on the powers of government to restrict speech, expression, and religion.

- If a judge decides police obtained evidence unlawfully, what might the judge do?

- Suppress (exclude) the evidence pursuant to the exclusionary rule and the Fourth Amendment.

- What document contains the fundamental principles underlying all U.S. laws?

- U.S. Constitution

- Why are case decisions important?

- They establish law, precedent (stare decisis)

- What concept describes the weight given to a prior decision by a court?

- Legal precedent (stare decisis, authority)

- The First Amendment was ratified in 1791, thus is couldn’t possibly be applied to the complicated issues we face today regarding online speech. True/False

- False

- The First Amendment only says what Congress cannot do, but the the Executive and Judicial branches can do whatever they want. True/False

- False

The First Amendment

Here’s the First Amendment (I added the line breaks to separate each phrase).

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,

or prohibiting the free exercise thereof;

or abridging the freedom of speech,

or of the press;

or the right of the people peaceably to assemble,

and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Interesting 1st Amendment facts and conclusions by John

- Ratified 1791

- Word count: 45

- Words unchanged since 1791 (232 years)

- Number of words written since 1791 about what these 45 words mean? Millions and probably billions!

- The phrase “free speech” means totally different things to different people.

- To be more precise, instead of talking about “free speech”, first consider what the First Amendment protects.

- The First Amendment protects from government limitations upon speech.

- Government limitations upon speech could be criminal (e.g. an arrest and criminal prosecution based on speech or expression)

- Government limitations upon speech could be civil (e.g. using the power of the civil courts to make someone pay money because of their speech or expression, such as in a defamation lawsuit (libel, slander).

- One of my frequent corrections is reminding students to capitalize First Amendment, since it is a proper noun.

Speech categories and my diagrams

Let’s outline a way to categorize speech, starting with the biggest category (everything) and then smaller and smaller subsets of that.

I think my diagrams help categorize different types of speech, and what consequences might result from that speech. Think of these six categories.

- All speech (any speech or expression)

- Annoying speech (speech that annoys at least one person)

- Unfriending speech (speech that annoys a person enough that they take some type of action, like their speaking, unfriending, boycotting, etc.)

- Protected speech (speech that is protected by the First Amendment in some way)

- Civilly actionable speech (a very small subset of the above, speech that someone could sue for and make the person pay money in damages)

- Criminally actionable speech (a tiny, infinitesimal subset of the above, speech that could get someone arrested and prosecuted).

Within those six categories, three relate to government consequence, or not:

- Protected speech

- Civilly actionable speech

- Criminally actionable speech.

John’s diagram part 1 – the categories

Here we show the five main categories, but they are not to scale, they are big enough so you can see the color scheme, the labels, and a little bit of description.

The categories are:

- All speech

- Annoying speech (might annoy someone)

- Unfriending speech

- Civilly actionable speech

- Criminally actionable speech

John’s diagram part 2 – “Protected speech”

Now we are highlighting “protected speech” with this diagram.

Of course, this is a bit of a simplification.

Note that certain speech might be “protected” from any criminal prosecution, but fair game for a civil litigation.

Remember the key point which is protection from government interference.

Just because speech is protected from government interference does not mean the speech can be made without any type of consequences at all. People might protest, boycott, and etc.

We can debate “cancel culture”, but if we are talking about the First Amendment, we need to remember the First Amendment is about what government can do, not about what “society” and individuals can or should do.

John’s diagram part 3 – closer to scale!

This diagram is a little bit closer to scale.

The main takeaway here is the vast majority of speech is protected by the First Amendment. A small sliver could be subject to valid civil claims, and a really tiny piece could be criminally punished.

Let’s get lawyerly

[This section is a work in progress]

Court decisions and the law need a process for deciding whether statements are criminally actionable or civilly actionable. And for deciding whether a government action regarding speech is lawful or violates the First Amendment.

So here are some principles.

- Is the government restriction on speech “content neutral” or “content based”?

- Content neutral means the restriction does not depend on what the content of the speech is

- Content based means the restriction is about certain types of speech

- Certain speech restrictions will get “strict scrutiny” by the courts

- If the government restriction on speech is not content neutral, it needs to be narrowly tailored to serve a significant government interest, and will get strict scrutiny

- Government may restrict or punish speech that presents a “clear and present danger” or “imminent” danger

- “Fighting words” are not protected speech. Fighting words are words that inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace. (Chaplinksy v. New Hampshire, 1942)

- Defamation: A civil cause of action for defamation. Defamation can include libel (written speech) or slander (spoken). A plaintiff must establish that the defendant said something false, and that it caused financial harm (damages). If the plaintiff is a public figure, they must also show actual malice.

First Amendment Chronology and Case Progression

[This section is a work in progress]

An evolution of law and interpretation.

First Amendment ratified in 1791

Interesting concepts and cases that touch upon the First Amendment

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964). In this civil defamation case, the U.S. Supreme Court provides greater protection for speech about public officials and public figures, requiring a defamation case to show “actual malice”. Actual malice meaning the person knew what they said was false, or said it with a reckless disregard for whether it was false.

Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969). In this criminal case, the U.S. Supreme Court limits what speech can be charged criminally as an incitement to violence, requiring intent and a likelihood of imminent lawless action.

There is a lot of speech out there

There is a lot of speech out there, and a lot of it contains false information, conspiracy theories, hateful speech, criminal speech, and more. Whether for profit, political gain, nation-state advantage or simple ignorance, there is lots of propaganda, misinformation, and disinformation. source

Anti Slapp Law Resources:

Anti-SLAPP and Free Speech in Defamation & Emotional Distress Cases