California can share your baby’s DNA sample without permission, but new bill could force state to publicly reveal who they’re giving it to

The State Owns Your Newborn Blood Spot DNA

After more than a decade of CBS reporting on the biobank, this is the first time California officials have refused to reveal to us who has access to California’s newborn bloodspots. Under previous administrations, the agency regularly provided that information under the California Public Records Act.

While California’s Newborn Genetic Biobank is undoubtedly saving lives, the appearance of state secrecy is raising concerns. In response, some California lawmakers are pushing for transparency, but they face an uphill battle at the State Capitol. (To learn more about newborn blood storage, and how to opt out, click here.)

For some, newborn DNA testing is a lifesaver

“He was a very cute, very adorable baby,” Ronnie’s dad said, as he described seeing his son for the first time, “and perfectly healthy.”

At the time, the new father (who for medical privacy reasons asked us not to use full names in this report) didn’t think much about what happened next. Like every baby born in the state, Ronnie got a heel prick shortly after birth. That blood filled six spots on a special card used to test babies for dozens of disorders that, if treated early enough, could prevent severe disabilities or death.

A couple of days after taking their seemingly healthy boy home from the hospital, they got a call from the local pediatrician, who said the child was diagnosed with “no immune system at all.” They learned Ronnie’s heel prick revealed that he had a rare genetic disorder called SCID, also referred to as “bubble boy disease” after David Vetter, who lived his life in a bubble in the ’70s before dying at age 12.

Ronnie’s first infection could have killed him, but thanks to research, the disease is no longer a death sentence. Ronnie was rushed to UCSF Medical Center where he received lifesaving gene therapy. That’s where he met Dr. Jennifer Puck, who created the test that saved Ronnie’s life.

“I could never have developed a newborn screening test for SCID if we hadn’t had stored dried blood spots,” Puck said.

Doctors only need a few of the baby’s blood spots for their own lifesaving genetic test, but the rest becomes the property of the state and can be purchased by outside researchers.

While newborn bloodspots had been used in research for years, the SCID test was the first to be developed using extracted DNA from bloodspots stored in California’s massive newborn genetic biobank. The state doesn’t extract or sequence the DNA from bloodspots, they store the physical bloodspot samples, which researchers can purchase for state-approved studies and extract or sequence the DNA themselves.

“You have to go through a scientific review to say, is this a worthwhile project,” Puck explained.

Many parents don’t know the state is collecting newborn DNA

California has amassed what’s believed to be the largest stockpile of newborn bloodspots in the country. It is one of the few states that is still storing every baby’s bloodspots indefinitely, without first getting parents’ consent.

Therein lies the concern. Back in 2018, CBS News California randomly selected six new moms to ask what they knew about the newborn genetic testing program. When asked whether they knew the state was storing their children’s DNA, all said they did not; when asked if they felt they should have been made aware, they agreed they should have.

“I didn’t know there was repository of every baby born in the state,” one concerned mother said. Another added, “There just should be accountability and transparency.”

Some states allow parents to opt-in to storage or give informed consent. California automatically stores your baby’s genetic material, then sends you home from the hospital with a pamphlet that points you to a website where you can request that they destroy the sample. But first, you’d have to know they were storing it in the first place.

“I feel like that’s something that should have been discussed with us in person,” one concerned mother said.

“Everyone who came into our room gave us another pamphlet,” another added.

A CBS News-Survey USA news poll found three-quarters of new parents had no idea the state was storing their baby’s leftover bloodspots indefinitely or that they had the right to have their child’s sample destroyed.

“Blood is intrinsically personally identifiable,” one mother pointed out.

Could privacy violations, lawsuits threaten California’s biobank?

Public records CBS News California obtained from the California Department of Public Health in 2010 revealed that, in addition to research, newborn genetic bloodspots are also used by law enforcement.

Our reporting found at least five search warrants and four court orders for identified blood spots, and that was before the Golden State killer case made genetic geology a common law enforcement tool.

Since then, we know at least one cold case was recently solved with the help of California’s newborn blood spots.

A lawsuit alleges police subpoenaed a 9-year-old’s newborn samples from New Jersey’s biobank to link his father to a cold case rape before the child was born. And Texas reportedly provided race-specific blood spots to the federal government to build a DNA database.

But when we recently asked California’s health department for an updated list of research and law enforcement requests, the agency denied us, saying it “is no longer tracking” that information like it used to and it’s “not required to create a record” telling us who has access to California’s stored DNA:

“Unfortunately, GDSP is unable to provide you the information as requested. Previously, GDSP provided you with an existing spreadsheet of research studies… GDSP has since moved to a new computer program for collecting this data and is no longer tracking research studies using the spreadsheet and the table. Pursuant to Government Code section 6252, subdivision (e), and established case law, a public agency is not required to create a record that does not exist at the time of the PRA request. (See Haynie v. Superior Court (2001) 26 Cal.4th 1061, 1075; Sander v. Superior Court (2018) 26 Cal.App.5th 651, 665-666.)”

For years everyone from privacy advocates to lawmakers to genetic detectives have warned California’s secrecy could ultimately harm trust in the biobank.

“People have the right to choose how their DNA is used and how their children’s DNA is used,” said Cece Moore, a genetic detective.

Texas is one of several states that had to destroy their bloodspots after being sued for storing them without consent. It was a devastating blow to the research community and many worry that California’s biobank could be next.

“I think we need to find ways that parents can consent without harming research,” Puck said.

Medical community opposed allowing opt-ins in the past

The medical community has historically opposed allowing parents to opt into storage, for a number of reasons.

“If you required consent, a lot of people would say yes, and some people would say no,” explained Puck. “And the people who say no, we don’t know if that’s a biased sample. And so that would skew the biobank.”

Puck adds there is also a possibility that the parent could say no and then later really come to regret that decision.

However, the California Constitution guarantees the right to “pursue and obtain privacy” and state law “prohibits health care providers from sharing, selling, or using patient medical information without consent.”

Legal experts involved in lawsuits in other states tell us that it’s only a matter of time before California’s biobank is taken to court. If the state proactively allowed consent, they say it could ultimately help save the biobank.

Despite support, why has newborn DNA legislation stalled?

The Texas Law Review cited our ongoing reporting on this issue and so did legislative analysts when our reporting led to a bill last year that would have let parents opt out of storage or research before the samples were stored. Even the powerful medical lobby removed their opposition to the bill after the author made significant changes.

The bill passed three different committees, at least one with a near-unanimous vote. Then the bill quietly died in January behind closed doors in the Senate suspense file. Why? Money and politics. Any bill that is estimated to cost more than $150,000 is sent to the “suspense file” where, in a budget deficit year, many bills go to die.

The state health department claimed it would cost roughly $4 million to implement, plus ongoing costs of over $1 million a year, to give parents the right to opt out of storage or research before the state automatically stores their child’s DNA.

An independent appropriations analysis of a similar bill in 2015 estimated $120,000 to implement that bill with half a million in ongoing costs.

Neither California’s health department nor the Senate Appropriations Committee could provide an accounting or evidence of the estimated costs. But maybe more importantly, the bill should not have cost taxpayers anything because research fees are supposed to pay for the program.

Still, the Appropriations Committee chair has the power to kill any bill they want to by holding it in the “suspense file,” where it automatically dies without a vote. Then-chair, Glendale Senator Anthony Portantino, decided to do just that, ultimately killing the bill before the rest of the senate got a chance to vote.

The appropriations analysis of the bill clearly states that CDPH’s estimated costs would be covered by the Genetic Disease Testing Fund (GDTF), not the general fund. State regulation requires the biobank program pay for itself through the (GDTF), by charging researchers to use the bloodspots.

The committee analysis does cite potential additional “(c)osts to local registrars for administration,” however, regulations are clear: “It is the intent of the Legislature that the program… be fully supported from fees collected…”

We asked the CDPH Office of Communications to confirm that any costs related to the bill would have been covered by increased fees charged to researchers. The agency did not respond. However, we did receive an unsolicited notice that a California Public Records Act request had been submitted on our behalf. Under state law, that gives the agency two weeks to decide if it will answer our questions.

We also asked the Appropriations Committee and former chair Asm. Portantino, to clarify why they chose to let the bill die in the suspense if the bill would not have created any additional costs to the state?”

They did not respond to repeated emails.

Two new California bills introduced in 2024

Privacy advocates are at it again with two new bills this year.

Prompted by our recent reporting, SB 1099 would force the state to publicly reveal, among other things, who’s using California’s newborn bloodspots and why.

The other, SB 1250, would amend California’s Genetic Information Privacy Act to require the state government to follow the same rules as consumer genetic testing companies and get consent before using or sharing your genetic data.

“Consent is definitely a good option,” said Ronnie’s dad, who supports the biobank and consent.

Genetic data from those stored blood spots has undoubtedly saved thousands of babies, including Ronnie’s, who is thriving — outside of a bubble. source

The State Owns Your Newborn Blood Spot DNA

The #ReportersNotebook entry below was first published in 2015. Since then, we’ve identified new concerns. Please also see the updated story here:

If you or your child was born in California after 1983, your DNA is likely being stored by the government, may be available to law enforcement and may even be in the hands of outside researchers.

Like many states, California collects bio-samples from every child born in the state. The material is then stored indefinitely in a state-run biobank, where it may be purchased for outside research.

State law requires that parents are informed of their right to request the child’s sample be destroyed, but the state does not confirm parents actually get that information before storing or selling their child’s DNA.

Reporter Julie Watts has learned that most parents are not getting the required notification. She also discovered the DNA may be used for more than just research.

In light of the Cambridge Analytica-Facebook scandal and the use of unidentified DNA to catch the Golden State Killer suspect, there are new concerns about law enforcement access, and what private researchers could do with access to the DNA from every child born in the state.

For more information on how your child’s specimen might have been used for research, email newsmom.com@gmail.com

#ReportersNotebook 2015

Do you know if your child’s DNA is being stored in a government database? If you live in California, or at least 20 other states, it likely is.

In this report for CBS San Francisco, we took a closer look at the life-saving “Newborn Screening Test.”

No one disputes the need for, or benefits of, the mandatory genetic screening program. However, the controversy stems from the lack of disclosure about what they do with your child’s newborn blood spot DNA after the test.

For decades, state governments have been collecting, storing and “selling” babies’ DNA to private companies for research without parental consent—DNA from a blood test that you pay for.

Newborn Screening Test

Every baby born in the U.S. is pricked on the heel at birth so that their blood can be screened for rare genetic disorders. The test is required by law and is even performed following home births.

The Newborn Screening Program allows babies with rare genetic disorders to receive early diagnosis and treatment, often saving their lives.

SaveBabies.org outlines the screening process and the benefits of the test. It also highlights stories of lives saved because of the test.

Genetic screening really is a miracle of modern science.

However, in at least a couple dozen states, the blood spots that are used for the screening are not destroyed after the test.

Now, storing your child’s DNA is not inherently a bad thing. State researchers use the stored blood spots to come up with new genetic tests for other diseases, ultimately saving more lives.

What They Don’t “Tell” You

The issue for many, however, is the fact that some states store and sell your babies’ DNA without your consent or even knowledge.

In addition to state researchers, law enforcement and lawyers can obtain your child’s DNA, and private companies can purchase it for research.

(Note: The California Newborn Screening Program insists that the state does not profit from the sale of blood spots, rather private companies reimburse the state for costs incurred—often tens of thousands of dollars per blood spot.)

Parents do have the right to ask that the blood spots be destroyed, but did you know they even existed? Most don’t.

We asked the California Department of Public Health how it informs parents their child’s blood spots will be stored after the Newborn Screening Test. The state response made me laugh out loud.

The information for parents about storage and use of blood spots is provided on pages 12 and 13 of the Newborn Screening brochure. In addition to being available on the internet in multiple languages, healthcare providers give the brochure to parents prenatally and at birthing centers and hospitals.

Between trying to figure out how to nurse my newborn, change a diaper, sleep train my baby, learn the “5 S’s,” find time to shower, research vaccines, get to doctors’ appointments, interview nannies and deal with insurers, it never occurred to me to comb through the four folders of forms and information I was sent home from the hospital with to find that brochure so I could flip to page 12 and 13.

You’d better bet I did just that, though, as soon as I started researching this story. You know what I found? A “Newborn Screening Test Request Form (TRF),” filled out in a stranger’s handwriting that didn’t even have a spot for my signature.

Requesting/Destroying Your DNA

California’s genetic testing program began in 1980, so I took advantage of my rights in California to request information about how my DNA had been used.

Turns out the state didn’t begin “storing the DNA” until 1983.

So, I requested the same information about my sister and my daughter, but I was told that their specimens had “not been used for research.”

I then asked to have my daughter’s DNA/blood spot card returned to me so that I could ensure it would not be used without my consent. This is the response I received:

Unfortunately, department policy does not allow for specimens to be released to an individual, “The Newborn Screening Program tests newborn specimens to provide medical results for disorders for which we screen. The residual specimens may be used for research concerning diseases of women and children. When requested by parents or an adult who was screened as a child, the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) will destroy newborn screening specimens so that they are not available for research or CDPH will send a portion of the specimen safely to another facility for further medical testing. CDPH does not release individual specimens to members of the public pursuant to requests by those individuals.”

So in short, you should trust that the agency that took your child’s DNA without your consent will destroy it upon request. They will not return that DNA to you even though it’s technically yours. I have not yet asked if they will return it to my pediatrician.

Also, note this disclaimer from the state:

You have a right to ask the Newborn Screening Program not to use or share your or your newborn’s information and/or specimen in the ways listed in this notice. However, we may not be able to comply with your request.

Though, keep in mind that by destroying your child’s sample, you are preventing researchers from using it to come up with new, potentially life-saving, tests. California has one of the largest databases in the country, and as a result can test for more genetic disorders than any other state.

After hearing from parents whose children have been saved by those tests, I opted to request that the state simply mark my daughters “specimen” as “do not use for outside research.”

Privacy

Now, to be clear, the state does not sequence the DNA, so it’s not exactly a “DNA database.” Rather, the state stores your child’s blood spots, which can then be sold for research.

It’s the researchers that extract–and potentially sequence–your child’s DNA.

The state claims the information is “de-identified,” so your baby’s DNA can’t be tracked back to the child. However, Yaniv Erlich of Columbia University and the New York Genome Center says there is no way to guarantee that.

As we point out in our CBS Report:

His research demonstrated how easy it is to take anonymized DNA, cross-reference it with online data and connect it to a name. “You need to have some training in genetics, but once you have that kind of training the attack is not very complicated to conduct,” he said.

Once he realized that there’s no guaranteed privacy when it comes to DNA, Erlich took it a step further and created dna.land. It’s essentially a crowd-sourced database where people voluntarily donate their DNA to share with scientists.

Its motto: “Know your Genome to help science.” Similar to 23 and me, you can also find long-lost relatives at dna.land. However, dna.land is free and run by academics at Columbia University and the New York Genome Center.

Is the state database legal?

Even if researchers couldn’t track your child’s DNA back to your child, the states can. They obviously have to be able to find your DNA if you ask to have it destroyed.

We requested public records and found that the state also hands over that DNA to law enforcement. It can be, and often is, subpoenaed. However, as far as we know, no one has yet been convicted of a crime based on their blood spot DNA in the state’s database.

A fairly new federal law requires that any federally-funded researchers using newborn blood spots must first get parental consent. However, that does not apply to state-funded or privately-funded research.

For now, the legal right to store and sell the dried blood spots is determined by each state. However, Pediatrics reported some states “may be acting outside the scope of their legal authority.”

Parents in Texas sued the state for selling their children’s blood without consent. It was later determined that the state sold blood spots to pharmaceutical companies for research and “loaned” it to the U.S. Armed Forces.

The state settled with the families out of court and subsequently destroyed the DNA taken without parental consent. Texas has now enacted a law allowing parents to “opt in” to the program.

The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) was also sued for establishing a biobank without parental consent. Samples were allegedly used for research by drug companies and equipment manufacturers.

The Minnesota Supreme Court ruled that written, informed consent is required for storage, use or dissemination of any remaining blood samples or test results after completion of a newborn screening.

Ultimately the state was forced to destroy hundreds of thousands of test samples and results. Minnesota later enacted a law requiring written informed consent before newborn samples can be used for research.

That is something the medical community in California is trying to avoid.

We asked the California Department of Public Health why it does not allow parents to opt in, or at least provide informed consent, before storing and selling a child’s DNA. The state declined an interview and ultimately provided this response after our story aired.

Healthcare providers at California’s many birthing facilities give parents informational brochures about opting-out of blood spot storage. Since parents of newborns have many other concerns shortly after birth, this procedure allows them to make that decision at any time, without pressure. Parents can then contact the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) and learn more about their options from knowledgeable professionals who are directly involved with the Newborn Screening Program.

Again, I had to point out to the state that neither I, nor any new mother I’ve spoken with, recall ever being informed that our child’s DNA would be stored and/or sold after their genetic test.

I’ve now asked if they keep any records or have any evidence that parents are, in fact, informed. I’ve also asked the state to elaborate on why parents are not offered the opportunity to provide “informed consent for the storage and sale of their child’s blood spots at some point during in the 9 months leading up to the delivery.” I am still awaiting a response.

Lawmakers Trying To “Fix It”

Earlier this year, California Assemblyman Mike Gatto introduced the DNA Privacy Bill that would require the state to get informed consent from parents before storing and selling a child’s DNA.

“Whenever data is stored, data can fall into the wrong hands. Imagine the discrimination a person might face if their HIV status, or genetic predisposition to a mental disorder were revealed to the public,” said Gatto. “Parents should have the right to protect their children and people should have the right to control how their personal medical records are used once they reach adulthood.”

The bill was strongly opposed by the biotech, medical and research communities. However, after five revisions, the only remaining opposition was from the California Hospital Association. CHA declined to comment for our story.

Here are excerpts from the opposition to informed consent:

The California Hospital Association (CHA): ...this bill would also increase the administrative burdens on hospitals, physicians, and new mothers which, in turn, will increase health care costs.The University of Southern California (USC): California's database is internationally recognized as a critical public health asset and allows for the study of these rare diseases among its diverse communities.The American Academy of Pediatrics and March of Dimes (CA Chapters): ... oppose any amendments that would link consent for storage and research of newborn screening blood spots with the initial collection and testing of the blood spots.California Children's Hospital Association (CCHA): ... the current California blood spot database is an internationally recognized public health asset because of its size and diversity.... Implementing an informed consent policy will require significant financial resources...The University of California (UC): ... this measure could significantly limit the availability of the valuable data and biosamples collected by the CNSP for research use.

The bill ultimately failed. Gatto says he will re-introduce it next year.

Bottom Line

The bottom line is that newborn genetic testing saves lives. Without access to the stored blood spots from the millions of babies born every year, researchers say they would not have been able to create the life-saving tests to begin with.

The question remains: Should parents have the right to consent/opt in to the state storing and selling their child’s DNA after the test is performed?

Currently, the state admits it does not obtain consent, and the industries that benefit from the program are fighting to keep it that way. The general belief is that many parents would not consent if given the option, and the scientific community would ultimately suffer. source

DNA of every baby born in California is stored. Who has access to it?

State law requires that parents are informed of their right to request the child’s sample be destroyed, but the state does not confirm parents actually get that information before storing or selling their child’s DNA.

CBS station KPIX has learned that most parents are not getting the required notification. And the DNA may be used for more than just research.

In light of the Cambridge Analytica-Facebook scandal and the use of unidentified DNA to catch the Golden State Killer suspect, there are new concerns about law enforcement access, and what private researchers could do with access to the DNA from every child born in the state.

DNA of every baby born in California is stored. Who has access to it?

State law requires that parents are informed of their right to request the child’s sample be destroyed, but the state does not confirm parents actually get that information before storing or selling their child’s DNA.

CBS station KPIX has learned that most parents are not getting the required notification. And the DNA may be used for more than just research.

In light of the Cambridge Analytica-Facebook scandal and the use of unidentified DNA to catch the Golden State Killer suspect, there are new concerns about law enforcement access, and what private researchers could do with access to the DNA from every child born in the state.

The Lifesaving Test

It all begins with a crucial and potentially lifesaving blood test.

The Newborn Genetic Screening test is required in all 50 states, and is widely believed to be a miracle of modern medicine.

Nearly every baby born in the United States gets a heel prick shortly after birth. Their newborn blood fills six spots on a special filter paper card. It is used to test baby for dozens of congenital disorders that, if treated early enough, could prevent severe disabilities and even death.

It’s estimated that newborn screening leads to a potentially life-saving early diagnosis each year for 5,000 to 6,000 children nationwide.

The California Department of Public Health reports that from 2015-2017 alone, the Newborn Screening test diagnosed 2,498 babies with a “serious congenital disorder that, if left untreated could have caused irreparable harm or death.”

But, unless you or your child is diagnosed with one of these disorders, the test is often lost in the fog of childbirth.

KPIX randomly selected six new moms and asked what they knew about their child’s genetic test.

Three of the moms remembered the heel prick, while the other three say they think they knew about the test. But, like most parents, none knew what happened to their baby’s leftover blood spots after the test.

They were shocked when KPIX reporter Julie Watts explained it to them.

Your rights after the test

The lab generally only needs a few of the blood spots for the baby’s own potentially lifesaving genetic test. They use to collect five blood spots total from each child in California, they’ve now increased that to six.

Some states destroy the blood spots after a year, 12 states store them for at least 21 years.

California, however, is one of a handful of states that stores the remaining blood spots for research indefinitely in a state-run biobank.

Even though the parents pay for the lifesaving test itself, the child’s leftover blood spots become property of the state and may be sold to outside researchers without the parent’s knowledge or consent.

“I just didn’t realize there was a repository of every baby born in the state. It’s like fingerprints,” new mom Soniya Sapre responded.

Amanda Feld, who had her daughter 15 months ago, was concerned in light of recurring data breaches. “We know that companies aren’t very good at keeping data safe. They try,” she said.

New mom Nida Jafri chimed in, “There should be accountability and transparency on what it’s being used for.”

“Blood is inherently or intrinsically identifiable,”added Sapre.

Some states allow parents to opt-in or give informed consent before they store the child’s sample.

In California, however, in order to get the potentially lifesaving genetic test for your child, you have no choice but to allow the state to collect and store the remaining samples.

You do have the right to ask the biobank to destroy the leftovers after the fact, though the agency’s website states it “may not be able to comply with your request.”

You also have the right to find out if your child’s blood spots have been used for research, but you would have to know they were being used in the first place and we’ve discovered that most parents don’t.

Samples used to save more lives

Dr. Fred Lorey, the former director of the California Genetic Disease Screening Program, explained that blood spot samples are invaluable to researchers.

“They’re important because these samples are needed to create new testing technology,” Lorey said.

He explained that they’re primarily used to identify new diseases and improve the current tests, ultimately saving more babies

With nearly 500,000 births a year, California’s biobank is, by far, the largest and is crucial for research nationwide.

According to the Department of Public Health, more than 9.5 million blood spot samples have been collected since 2000 alone. The state has stored blood spots since 1983.

As a result, California can now test newborns for more than 80 different disorders, more than any other state. The standard panel nationwide is around 30 disorders.

But researchers with the California Genetic Disease Screening Program aren’t the only ones with access to samples stored in the biobank.

Blood spots are given to outside researchers for $20 to $40 per spot.

Regulations require that the California Genetic Disease Screening Program to be self-supporting.

“It has to pay for itself,” Lorey noted. Allowing outside researchers to buy newborn bloodspots helps to recoup costs.

According to biobank records, the program sold about 16,000 blood spots over the past five years, totaling a little more than $700,000. By comparison, the program reported $128 million in revenue during the last fiscal year alone, mostly generated by the fees parents pay for the test. Parents are charged around $130 on their hospital bill for the Newborn Screening Test itself.

Making money off your DNA

But while the state may not be making money off your child’s DNA, Lorey admitted that there is the potential for outside researchers to profit off your child’s genetic material.

“Do any of those studies result in something that the company can make money from?” reporter Julie Watts asked Lorey in a recent interview. “Could they create a test or treatment that they ultimately profit from?”

“Theoretically, yes,” Lorey admitted. “I’m not aware of any cases that that’s happened because virtually all, not all, of these researchers that have made requests are scientific researchers.”

He explained that researchers who request the spots must meet specific criteria. Their studies must first be approved by a review board. They’re also supposed to return or destroy remaining blood spot samples after use.

However, privacy advocates point to the Cambridge Analytica-Facebook scandal where third-party researchers were supposed to destroy data, but instead used it for profit – and untimely to attempt to influence a presidential election.

Watts pressed Lorey on that point.

“So there is no possibility a researcher may request blood spots for a specific research experiment … but then keep blood spots without the department’s knowledge to be used for other purposes?” she asked.

“I want to say no” he said. “But I’m not ready to say no because I know how humans can be sometimes.”

“De-identified DNA”

However, Lorey stressed that the blood spots cards, stored in the state biobank, are “de-identified.” There is no name or medical information on the card, just the blood spots and a number.

Lorey explained the identifying information is stored in a separate building and after a few years is microfiched so it’s not even kept on a server. Samples do need to be re-identified for various reasons, but Lorey says, in those cases, parents are notified.

And to be clear, he stressed, there is also no genome database. The state does not sequence or extract the DNA from the blood spots collected, although a researcher might, depending on the study.

Privacy advocates, like Consumer Watchdog’s Jamie Court insist DNA is inherently identifiable.

“There is no such thing as de-identified DNA,” Court said. “The very nature of DNA is that it identifies you and your genetic code specifically.”

Court points to the recent case of the Golden State Killer. Investigators used public ancestry sites to identify a murder suspect using decades-old unidentified DNA from a crime scene.

And we’ve learned, researchers aren’t the only ones with access to the blood spots.

Law enforcement access

A public records request revealed coroners often use blood spots to identify bodies, and at least one parent requested blood spots to prove paternity.

Law enforcement also can — and does — request identified blood spots. We found at least five search warrants and four court orders, including one to test a child’s blood for drugs at birth.

According to the Department Of Public Health, “Only a court order can provide a third-party (including law enforcement) access to an identified stored specimen without parental consent.”

“I think the storage of DNA for purposes other than medical research without informed consent clearly is violating a duty and a trust that the state has to the public,” Court said. “What are they trying to hide?”

State law says parents should know – but they don’t

According to the Department of Public Health, it’s not hiding anything. The agency points to page 13 of the Newborn Screening brochure which does disclose that the blood spots are stored.

“In addition to being available on the Internet in multiple languages, healthcare providers give the brochure to parents prenatally and at birthing centers and hospitals,” the Department of Public Health stated.

We asked the six new moms to bring in all the paperwork they collected from the hospital. Only one of the six women actually had the required newborn screening pamphlet and she admitted that between delivering a baby and learning to raise a tiny human, she hadn’t found the time to flip to page 13.

“I feel like that’s something that should have been discussed with us in person, not on whatever page in a document,” another new mom, Lesley Merritt, responded.

Argelia Barcena added that they were not told the pamphlet was crucial or mandatory reading material. “I saw it as reference material, to refer to if needed, they dont tell you ‘you must read it,'” she pointed out.

Keep in mind new parents are generally sent home with folders full of paperwork including a variety of medical testing forms and pamphlets with information ranging from breastfeeding and vaccines, to sudden infant death and CPR.

“Everyone who came into our room gave us another pamphlet,” New Mom Amanda Feld pointed out.

In the case of the Genetic Screening Pamphlet, the moms agreed they wouldn’t have thought it was relevant to read after the fact unless their child was actually diagnosed.

And they’re not alone. We conducted an exclusive Survey USA news poll of parents with kids born in California over the past five years.

While a majority of parents reported that they did know about the life-saving test, three-quarters said they didn’t know the state would store the leftover blood spots indefinitely for research, and two-thirds weren’t sure they ever got the newborn screening information.

When we read the six moms that portion of page 13 that disclosed the blood spots could be used for outside research, they noted that it’s not clear the blood spots are stored indefinitely, available to law enforcement, nor that using blood spots for “department approved studies” means giving them to outside researchers.” P.13 states:

“Are the stored blood spots used for anything else? Yes. California law requires the NBS program to use or provide newborn screening specimens for department approved studies of diseases in women and children, such as research related to identify-ing and preventing disease.”

Lorey helped draft previous versions of the pamphlet. He agreed that the portion on page 13 “could be clarified,” but he said he believed the information included provides “adequate disclosure.”

He was surprised, however, when Watts showed him all the forms she was sent home from the hospital with and he acknowledged it could be difficult for parents to digest it all while also learning to care for a newborn.

He was also surprised to see the version of the newborn screening brochure that Watts was given.

Instead of the required 14-page pamphlet with the storage disclosure on page 13, she had a one page, tri-fold hand-out with no mention of storage, or a parent’s right to opt out of it. Instead there was a web link where parents could go “For more information…”

Required disclosure

State regulations say that parents are supposed to get the full 14 page pamphlet twice, once before their due date, and again in the hospital before the heel prick test.

But in practice, most parents say they didn’t even see the pamphlet until after the test, if they got it at all.

While the state says it “distributes more than 700,000 copies of the booklets to health providers each year,” it admits that it doesn’t track whether doctors are giving them out. It also does not confirm parents are informed of their rights to opt out of storage before storing or selling the child’s DNA.

Federal law

Under federal law, blood spots are currently defined as human subjects, and therefore require informed consent for federal research. But, that doesn’t apply to private researchers, and even that protection is about to expire when a new federal policy, known as the Common Rule, takes effect this year.

Following strong opposition from the research community, proposed protections for unidentified bio-specimens were stripped from the final rule. This means researchers won’t need consent to use de-identified blood spots, and, in some cases, can even use identified blood spots without consent.

It’s ultimately up to each state to develop their own policies on disclosure. Parents in Texas successfully sued the state, ultimately forcing their biobank to destroy samples taken for research without consent or disclosure.

State law

In California, the newborn screening law doesn’t actually authorize the state to store a child’s leftover blood spots after the test, or give it to outside researchers, it only authorizes the life-saving genetic test itself.

However, the newborn screening law does say that state may store samples of the mother’s prenatal blood, which is taken early in the pregnancy, but only if the mother opts in.

Parents don’t get to opt in to storing their baby’s DNA however and that was not decided by voters or lawmakers.

While the newborn screening law was enacted by the state legislature, the authorization to store every child’s DNA and sell it to researchers is actually in a separate regulation enacted by the Director of California Department of Public Health. It says that a child’s “blood specimen and information,” collected during a test paid for by the child’s parents, becomes “property of the state.”

“Any tissue sample that is given in a hospital or any medical facility, once it’s given, is no longer your property,” Lorey explained. “You can agree with that or disagree with that, but it happens to be the law.”

In 2015, former California Assemblyman Mike Gatto introduced a law that would have initially made both the test and storage opt-in. It was strongly opposed by the powerful hospital and research lobbies, and after several revisions, it died in the Senate Health Committee.

Health advocates said their primary opposition at the time was due to the fact that Gatto’s bill would have made both the test and storage opt in, and since the test itself is crucial to saving lives, they said the test should not be optional.

Researchers, on the other hand, oppose letting parents opt in to the storage too because they believe they would get fewer samples if parents had a choice.

But, that doesn’t seem to be the case in California.

Calif. moms opt in to prenatal

Along with newborn blood spots, the California Genetic Disease Screening Program also tests mothers’ blood in the first and second trimesters, and they’re allowed to opt in.

About 90 percent of pregnant women do opt in to letting the state store their own blood for research. And, unlike the newborn screening test, a majority of moms said they do remember the disclosures and pamphlets about their own genetic test, because they got them early in the pregnancy.

Eighty four percent of parents surveyed said they think they should get information about their child’s genetic screening at the same time they learn about their own. That would give them time — several months without the distraction of a newborn — to process the information and understand their rights before the child is born.

Many said they also should have the right to opt out of storage before their child’s DNA is stored, or at least give informed consent before it is sold for research.

The problem with opting in

Critics of the opt-in option point to Texas. Following a lawsuit by parents, the biobank was forced to destroy blood spots that were taken without consent to store them for research. Now Texas allows parents to opt-in to storage.

When the potentially life-saving screening test is given in Texas, a storage consent form with a matching ID number is given to the parents to take home from the hospital and review. Blood spots are not stored in the biobank unless parents sign and return the consent form. As a result, a significant percentage of samples are destroyed.

Critics note that many parents never return the form, likely in part due to the distractions of a new baby.

Ultimately, that hurts the biobank and researchers because they get fewer samples, and more importantly, fewer samples from certain communities.

This means that research performed with those samples may not be valid for the entire population. In contrast, research performed with samples from California’s biobank is considered very strong and applicable to all babies.

A Calif. opt-in solution

Parents and advocates we spoke with in California would like to see the informed consent given out early in the pregnancy, long before the due date, which may lead to a higher opt-in rate than in Texas.

An opt-in early in the pregnancy would require a system in place to match the mothers’ consent forms, collected in the first trimester, with the babies’ blood spots, collected months later by hospital staff.

Lorey said California already has a similar matching system in place for the prenatal genetic test so it does seem feasible.

Court believes parents should have the right to opt-in before their baby’s genetic material is collected and stored indefinitely by the state, though that would be fought hard by the powerful hospital and research lobbies in Sacramento.

“Informed consent basically means we should know what we’re donating a sample for,” Court said. “If hospitals and the medical complex is so concerned that if we knew that we might not donate our samples, than we absolutely need to know what they’re doing with them because it suggests there is a purpose beyond what we know.”

Meanwhile, a majority of parents surveyed said they would have opted-in to storage if given the chance.

Additionally, they said they’re more likely to destroy their child’s sample now than they would have been if they had been notified of their rights to begin with.

Both the California Hospital Association and the March of Dimes, which opposed previous legation that would have allowed parents to opt-in, say they are now open to improving the way the state informs parents that their child’s samples will be stored and “may be used to advance research.”

However, neither has an official position on allowing parents to opt-in to storage.

Short of an opt-in, Court said he thinks there should at least be a tracking mechanism to ensure every parent is getting complete and accurate information about the storage early in the pregnancy, before the DNA samples are stored.

Since state law already requires prenatal doctors to provide the information, Court notes, it wouldn’t be a stretch to require they also get a signature from moms, allowing the state to track whether or not parents are actually getting the information.

What next?

So the questions remain: Should parents have the right to know that their child’s DNA will be stored indefinitely in a state-run biobank and may be available to law enforcement? Should the state have to confirm that parents are informed of their rights before it stores and sells the child’s DNA? Who has the power to make that happen?

Karen Smith, appointed by Governor Brown, is the current Director of the Department of Public Health. She has the power to adopt new regulations.

Though, for a more permanent fix, lawmakers in Sacramento would need to pass new legislation.

We’ve shared our findings with several state lawmakers on the Assembly Privacy Committee. Many were shocked to learn that the state was storing DNA samples from every baby born in the state and selling them to outside researchers without parents’ knowledge or consent.

So far, however, none have shown any interest in giving parents the right to opt out of storage before the child is born, or even requiring the state to confirm parents are informed before storing their baby’s blood indefinitely. source

California collects, owns and sells infants’ DNA samples

The DNA data is supposedly anonymized, but one expert says the de-identification is easy to see through.If you were born in California since 1983, the state owns your DNA.

The data of every Californian born since that year is kept in a bland office building in Richmond, a city located in the eastern section of the San Francisco Bay Area.

That data’s not just passively kept, mind you: it’s also being sold, to third parties, for research purposes, according to CBS local station KPIX.

That biometric data, taken by a heel prick at birth to screen for 80 hereditary diseases, represents a wealth of information on an individual, from eye and hair color to pre-disposition to diseases such as Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Besides being sold – in purportedly de-identified form – to third parties, it’s also available for law enforcement requests.

None of this is new, mind you.

Dr. Jeffrey Botkin of the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children, which advises the Department of Health and Human Services on newborn screening, in June 2014 told Newsweek that this is a “long-standing issue and a controversy to a certain extent in the newborn screening field.”

The screening tests are generally mandatory under state law. When the program was first developed in the 1960s, Botkin said that the thinking behind it was that …

...the advantages for newborn screening were so compelling, it was appropriate or acceptable to have states simply mandate screening.

As of July 2014, 43 states allowed parents to decline the screening process based on religious beliefs or philosophical reasons, but the option is rarely exercised.

That’s probably due in no small part to the fact that parents only hear about the program during the hectic time when a mother in labor enters the hospital.

As Newsweek has reported, in most states, the blood spots are transferred to long-term storage banks run by state departments of health and retained for at least a few years.

In 12 states, they’re kept for 21 years or longer.

But California is one of just four states where dried blood samples become the property of the state: along with Iowa, Michigan and New York, it participates in a virtual repository, government-owned and -operated, that enables researchers to access the data and sometimes the blood spots themselves.

It’s not that the screening doesn’t help families. A prime example is the family of Luke Jellin, whose heel prick at birth led doctors to diagnose a rare metabolic disease.

KPIX quotes Luke’s mother, Kelly Jellin, a member of the Save Babies Through Screening Foundation:

Had he not been tested he would have been severely brain damaged, possibly would have had heart and kidney problems. If blood spots hadn’t been saved, they wouldn’t have been able to make the test that saved my child’s life.

Why isn’t this opt-in?

This all may surprise parents of the newborns, given that the tests are administered without parents’ informed consent.

Cases such as that of Luke Jellin notwithstanding, the question remains: why doesn’t the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) obtain permission before taking, saving, sharing and selling these blood spots?

When KPIX asked the CDPH for an interview on the issue, the request was denied.

In denying the interview request, the CDPH also failed to answer the question of why consent isn’t required for the test.

It turns out that information about the tests is buried on page 12 of the brochure about the Newborn Screening Program that hospitals give parents of newborns before they go home.

KPIX interviewed one mother, Danielle Gatto, who says she scarcely remembers the nurse mentioning tests performed at her two daughters’ births.

And she certainly didn’t turn away from her newborn to instead focus on a ream of paperwork, she noted:

I don’t think that any woman is in a state of mind to sit down and start studying up on the literature they send you home with.

The CDPH says that parents have the option of having the DNA samples destroyed: here’s the form to get that done.

Are the blood spots really de-identified?

The CDPH’s premise that DNA samples have been de-identified is questionable, one expert said.

Yaniv Erlich with Columbia University and the New York Genome Center told KPIX that there’s no way to guarantee that the samples can be rendered anonymous.

He’s actually found it quite easy to cross-reference anonymized DNA with online data and connect it to a name, he said:

You need to have some training in genetics, but once you have that kind of training the attack is not very complicated to conduct.

Erlich is, in fact, a supporter of sharing genomic information, for the sake of advancing biomedical research:

This is the only way that we can help families with kids that are affected by these devastating genetic disorders.

For her part, Gatto is unnerved by the unknowns of what could be done with the treasure trove of information stored in DNA samples and thinks that the state should at least ask for consent before storing and selling DNA:

We are at the beginning of a frontier of so much genetic research, there is no knowing at this point in time what that info could be used for. The worst thing as a parent is to think that a decision that you are making today may negatively affect your children down the road.

Her husband, Assemblyman Mike Gatto, introduced a DNA privacy bill this year that would have required signed consent on newborn screening.

The bill was killed after opposition – such as this letter from the University of California – from the state and the industry. source

Danielle Gatto has requested that her daughters’ blood spots be destroyed.

Bills to shed light on newborn DNA storage in California quietly killed or gutted

If you’re related to someone who was born in California since 1983, a portion of your DNA is likely in the state’s massive Newborn Genetic Biobank. In response to our decade-long investigation, lawmakers have introduced several bills intended to shed light on how the state is amassing and using California’s newborn DNA stockpile.

Only one of those bills is still alive, and while privacy advocates say it is a step in the right direction, recent amendments raise new questions about the appearance of state secrecy.

(To learn more about newborn bloodspot storage and how to opt out of storage or research, click here.)

A life-saving test

Every baby born in California gets a heel prick shortly after birth. Their newborn blood fills six spots on a special card which is used to test them for genetic disorders that, if treated early enough, could prevent severe disabilities – even death.

Doctors only need a few of the baby’s newborn bloodspots for their own life-saving genetic test. The leftovers become the property of the state and are stored indefinitely in California’s massive Newborn Genetic Biobank.

California State Secrets

According to the state, there has never been an outside audit of how California’s stored newborn DNA samples are being used by the state, law enforcement, or independent researchers.

Throughout our decade-long investigation, CBS New California has reported on multiple law enforcement requests for identified newborn bloodspots, and the thousands of de-identified DNA samples that are sold each year to independent researchers.

For years, we’ve obtained those records from the state under California’s Public Records Act. The records have enabled us to show the public how our DNA is being used and highlight the program’s lifesaving benefits.

However, following the pandemic, the California Department of Public Health suddenly started refusing to disclose who is requesting California’s stored newborn DNA samples and why.

The agency told CBS News California that it “is no longer tracking” that information like it used to and is “not required to create a record” revealing who has access to our DNA.

Playing Politics with Newborn DNA

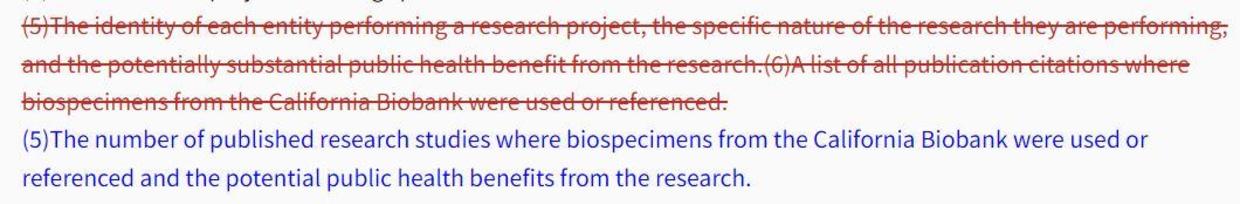

In response to our reporting, SB 1099 would have required the California Department of Public Health to publicly identify “each entity performing a research project, the specific nature of the research they are performing, and the potentially substantial public health benefit from the research.”

With no formal opposition or significant cost, the bill has sailed through the legislature with widespread support, and it is expected to head to the governor’s desk.

However, after the bill passed the Assembly, it was recently amended in the state Senate where lawmakers agreed to remove the part of the bill that requires the state to reveal who is using our DNA for research and why.

Instead, the bill now only requires the state to reveal the number of published studies and the number of California DNA samples used for research.

Privacy advocates say that is a small step in the right direction, but they question the continued state secrecy.

Calls for transparency

While California’s Newborn Genetic Biobank program has undoubtedly saved lives, the appearance of state secrecy raises concerns.

For years, everyone from privacy advocates to lawmakers has called for more transparency.

“People (should) have the right to choose how their DNA is used and how their children’s DNA is used,” said Cece Moore, a genetic detective, in a previous interview.

“What are they trying to hide?” asked Consumer Watchdog’s Jaime Court.

ALSO READ: Lawmakers could force California to stop storing your DNA without permission

Parents are in the dark

California has been storing newborn blood spots since 1983 and has amassed what’s believed to be the largest stockpile of newborn DNA samples in the country because it’s one of only a handful of states that stores the bloodspots indefinitely without parents’ permission.

You can ask to have your child’s DNA sample destroyed or opt out of storage for research after your DNA is collected and stored. However, you’d have to know the state was storing your child’s bloodspot in the first place, and most parents don’t know.

(To learn more about newborn blood storage and how to opt-out of storage or research, click here.)

In 2015, former Assemblyman Mike Gatto was the first to author a bill intended to increase transparency related to the Newborn Genetic Biobank. The bill would have allowed parents to opt out of bloodspot storage for research before the bloodspots were stored. It passed the Assembly and died in the Senate.

“There is no reason to be doing experiments on a child’s blood without informed consent,” Gatto said.

Over the years, the powerful medical lobby killed several bills that would have allowed parents to consent to storage and research. They argued that if given the choice, too many parents would opt out of storage, which could ultimately harm potentially life-saving research.

However, earlier this year, the medical lobby appeared to change its stance following amendments to another newborn genetic transparency bill, SB 625.

When the author agreed to amend the bill to allow parents to “opt-out” of storage instead of allowing them to “opt-in,” the medical lobby removed its opposition and changed its stance to “neutral.”

Privacy advocates plan to try again next year.

Find out if researchers have requested your child’s newborn bloodspot

Parents do have the right to find out if their own child’s bloodspots are being used for research and they can request the state destroy their child’s sample after it is stored.