California Penal Code § 170 – Misuse of the Warrant System – Crimes Against Public Justice

2022 California Code

Penal Code – PEN

PART 1 – OF CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS

TITLE 7 – OF CRIMES AGAINST PUBLIC JUSTICE

CHAPTER 7 – Other Offenses Against Public Justice

Section 170.

170. Every person who maliciously and without probable cause procures a search warrant or warrant of arrest to be issued and executed, is guilty of a misdemeanor. (Enacted 1872.)

Malicious Procurement of A Search or Arrest Warrant

Penal Code 170. Every person who maliciously and without probable cause procures a search warrant or warrant of arrest to be issued and executed, is guilty of a misdemeanor. (Enacted 1872.)

Penal Code Section 170 – Malicious Procurement of A Search or Arrest Warrant

Under Penal Code Section 1701, any person who “maliciously” procures a search or arrest warrant without “probable cause” is guilty of a misdemeanor.

A person acts “maliciously” if he intends to injure, annoy, or vex another person. A person acting with malice holds an “ill will” towards the victim. 2

Police officers may submit an “affidavit” to a judge which sets for the officer’s justification to request a search warrant or an arrest warrant. An affidavit is a written declaration made under oath. A judge may only authorize a search warrant or arrest warrant upon a finding of “probable cause.”2 When a judge determines whether there is probable cause to issue a search warrant, he or she “must make a practical, common-sense decision whether given all the circumstances set forth in the affidavit there is a fair probability that contraband or evidence of a crime will be found in a particular place.”4 A similar analysis occurs when a judge issues an arrest warrant. The judge must examine an officer’s affidavit in support of the arrest warrant and determine whether there is probable cause to believe that a crime occurred.

READ UP MORE….. on Malicious Prosecution and Thompson Vs. Clark and other SCOTUS Rulings here

This is a violation of the process also known as abuse of process not to be confused Due Process which is another part of this violation

The term ‘process’ refers to the proceedings in any civil lawsuit or criminal prosecution and usually describes the formal notice or writ used by a court to exercise jurisdiction over a person or property. Such process compels the defending party to appear in court, or comply with an order of the Court. It may take the form of a summons, mandate, subpoena, warrant, or other written demand issued by a court. When one files suit, one normally has a summons issued by the court which compels the defendant to appear within thirty days to contest the matter.

Abuse of process refers to the improper use of a civil or criminal legal procedure for an unintended, malicious, or perverse reason. It is the malicious and deliberate misuse of regularly issued civil or criminal court process that is not justified by the underlying legal action. to learn more about ABUSE of PROCESS click here and to learn abusing the Constitutinal Right to Due Process click here which involves several Constutional Rights afforded by the Amendments

- Fourth Amendment

- Fifth Amendment

- Fourteenth Amendment

- Malicious Prosecution and Thompson Vs. Clark and other SCOTUS Rulings click here

-

Prosecutorial misconduct – When prosecutors abuse their power by breaking the law or breaching a professional code of conduct.

Sources Cited / Notes:

1 Blog Article Published June 12, 2018.

2 In re V.V. (2011) 51 Cal.4th 1020, 1027-1028.

3 People v. Garcia (2003) 111 Cal.App.4th 715.

4 People v. Garcia (2003) 111 Cal.App.4th 715, 721.

How We Got the Fourth Amendment Exclusionary Rule and Why We Need It

The exclusionary rule evolved because of the ineffectiveness of the warrant procedure in preventing illegal searches and seizures, and it remains effective as a means of preventing the government from achieving the ends of its illegal activity and as a symbol of the justice system’s commitment to the citizen rights mandated in the fourth amendment.

The fourth amendment provides for a warrant system intended to prevent unreasonable searches and seizures; however, there is no specific constitutional provision for the exclusion of evidence illegally acquired. The framers of the Constitution exaggerated the effectiveness of the warrant procedure, but it does not follow that they were not serious about preventing the evils the warrant procedure was designed to address. The exclusionary rule was adopted by the courts as a rule of evidence to deal with the failure of the warrant system to address after-the-fact fourth amendment violations.

California Search Warrants – 7 Key Things to Know

In California, a search warrant is issued by a judge and authorizes law enforcement to search a person, a residence, a vehicle, a place of business, or any other specified area suspected of containing evidence of illegal activity.

Once police find the evidence they are seeking, the search warrant allows officers to seize that evidence.

Unless a search is

- authorized by your consent,

- incident to a lawful arrest, or

- under some other recognized exception,

it must be executed pursuant to a valid search warrant.

That said, there are many restrictions on when and how cops may execute California search warrants. Violations of these rules may result in a reduction (or even a dismissal) of your criminal charges.

In order to help you understand the law, our criminal defense attorneys will explain 7 key things to know about search warrants in California:

- 1. Who can authorize a search warrant?

- 2. What are the search warrant requirements for police in California?

- 3. Are there rules as to the use of informants?

- 4. How can a defense lawyer challenge the validity of a search warrant?

- 5. How are the police allowed to execute a warrant?

- 6. What is the knock and announce rule?

- 7. What is a motion to suppress evidence?

A judge issues and signs a search warrant.

1. Who can authorize a search warrant?

Although a search warrant is issued on behalf of the state (that is, by the prosecuting agency), the judge actually issues and signs it. 1 2 3 The purpose of having a judge issue the warrant instead of the police or a prosecutor is to ensure that a neutral, detached individual evaluates the circumstances of the criminal investigation.4

Before the judge can sign off, two requirements must be met: The judge must reasonably believe

- that a misdemeanor or felony has been committed, and

- that evidence of that criminal case is likely to be found in the place(s) described in the search warrant.5

If the facts presented in the warrant application are convincing, the judge must sign and issue the search warrant.6

Also, we should clarify the distinction between search warrants and two other common types of warrants.

- A California arrest warrant is usually issued when criminal charges have been filed, and it authorizes the police to arrest you on the charges.

- A California bench warrant is issued by a judge for violating some rule of court, such as failing to appear for your court hearing or failing to pay a fine that was required as a condition of probation.

2. What are the search warrant requirements for police in California?

There are certain requirements that law enforcement must meet in order to obtain a search warrant in California. They must show probable cause that the locations to be searched contain evidence, instruments or fruits of criminal activity.

The following are examples of the types of grounds on which a California search warrant may be issued:

- if the sought property was allegedly stolen

- if the sought property was allegedly used as a means to commit a felony

- if the sought property is evidence of the fact that a felony has occurred or that you have committed a felony

- if the sought property is in possession of someone who intends to use it to commit a crime or in the possession of another to whom they may have delivered it for the purpose of concealing it or keeping it from being discovered

- if the sought property reveals child pornography

- if an arrest warrant has already issued.7

It should be noted that if the sought property is held by an attorney, doctor, psychotherapist, or member of the clergy, a special procedure will be held before that evidence may be seized. Even then, the attorney, doctor, therapist, or clergyman must be the individual suspected of engaging in the alleged criminal activity.8

Before a judge issues a search warrant, they must have probable cause to do so.

Probable cause

“Probable cause” is a legal phrase. It refers to a “reasonable” belief that criminal activity is taking (or has taken) place.

So before a judge issues a search warrant, they must have a reasonable belief that the person/property specifically described in the warrant application (otherwise known as an “affidavit“) will be found in the searched location.9

Before finding that probable cause exists, the judge may question (under oath)

- the officer,

- prosecutor, or

- state investigator10 who applied for the warrant, and

- any witnesses that the requesting individual relied on to determine that a warrant was necessary.

These affidavits may be written or oral, and presented in person, via the telephone, by fax, or even e-mail.11 They also must contain the facts that establish the grounds for the application or the probable cause for believing that they exist.

Affidavits are under penalty of perjury.12

Search warrants v. other types of warrants

| Search warrant | Arrest warrant | Bench warrant | |

| Purpose | To search a location to seize evidence of a crime | To arrest you for committing a crime | To arrest you for defying court orders |

| Party requesting the warrant | Law enforcement | Law enforcement | Judge or law enforcement |

| Basis for issuance | Probable cause that there is evidence of a crime at a specified location | Probable cause that you committed a crime | Your failure to comply with court orders |

| Timeframe of issuance | Usually at the beginning of a criminal case | Usually at the beginning of a criminal case | Anytime during an open case |

3. Are there rules as to the use of informants?

Police routinely rely on information provided by informants. Informants are individuals who provide information about people, organizations, or activities to the police without the consent of those people or organizations.

That said, the judge must be informed of some of the facts that led the informant to their conclusion that there is alleged criminal activity.13 A mere opinion that a person or property is involved in a crime is therefore insufficient without evidence to support it.

Since it is the judge who must determine if there is probable cause to issue the warrant, they must believe that the informant’s information is reliable. This may be established by:

- the identity of the informer,

- past experiences with the informant in which they have proven to be reliable, and/or

- corroboration by the officer’s personal observations or other evidence.14

The informant’s identity

The judge may require disclosure of the informant’s name or may require them to give a statement under oath as to the information they provided to the police.15 However, just because the informant’s identity is disclosed to the judge does not mean it will necessarily be disclosed to the defense.

A judge is allowed to seal any or all of the affidavit to protect the identity of a confidential informant if that testimony helped establish the probable cause that led the judge to issue the warrant.16

Although the judge will not reveal the informant’s identity simply because you wish to use it to attack the judge’s finding of probable cause, they may ask the prosecutor to disclose it if your motion to traverse and quash the search warrant has merit.17

A lawyer can challenge the validity of a search warrant in multiple ways.

4. How can a defense lawyer challenge the validity of a search warrant?

Although motions to quash and traverse would be more appropriately explained in the final section titled “Motion to Suppress Evidence“, they merit discussion here. They directly relate to informants and the probable cause required to obtain California search warrants.

A motion to “quash and traverse” challenges the affidavit (and underlying probable cause) that the judge relied on upon issuing the California search warrant:

- A motion to traverse challenges the truth of the affidavit.

- A motion to quash challenges the sufficiency of the affidavit (that is, even assuming the facts are true, whether they rise to the level of probable cause).

Although these motions may be filed separately or together, the terms are often used interchangeably. We will discuss them as one for the sake of simplicity.

California criminal defense lawyers may assert motions to traverse and quash a search warrant in three types of hearings:

- in a Franks hearing (to assert that the author of the affidavit (otherwise known as the “affiant”) provided false information,

- in a Luttenberger hearing (to assert that the informant provided false information), or

- in a Hobbs hearing (which is based on a sealed affidavit).

Franks hearings

If you request a Franks hearing to quash and traverse a warrant because you believe the supporting affidavit contains false information, you must set forth the reasons why you believe that it is inaccurate.18 California criminal defense lawyers may do this by demonstrating that:

- the affidavit contained a false statement,

- the statement was made knowingly or with reckless disregard for the truth, and

- that the statement was necessary (that is, “material”) to establish probable cause.19

It should be noted that if the affiant intentionally leaves out material information, they will be deemed to have provided materially false information “by omission”.20

The court must hold an “in camera” hearing if the judge believes that you have effectively challenged the truth of the affidavit.21 An in-camera hearing is a private hearing held in the judge’s chambers.

During this hearing, the judge may question the affiant or informant to determine whether the affidavit is accurate, false, or misleading.22

If the criminal defense attorney succeeds in proving that

- the affidavit contained false material information, and

- the remaining information is insufficient to support a finding of probable cause,

the judge must quash the California search warrant.

Once the search warrant is quashed, any evidence that was seized under the warrant will be suppressed.23

*Suppressed evidence is discussed in the section titled “Motion to Suppress Evidence”.

Luttenberger hearings

When the affidavit supplying the probable cause contains information from an undisclosed informant, it is extremely difficult to establish that the affidavit is false – which is the standard to get a Franks hearing.

If the informant is not a material witness with respect to your guilt or innocence (an eyewitness to the alleged crime, for example), the prosecution is under no duty to disclose their identity.24

A Luttenberger hearing takes place when you want to attack the truth of the affidavit but do not know the identity of the informant. In this hearing, the California criminal attorney may request information about:

- the informant’s reliability,

- their motive for providing information (for example, was the informant paid or offered leniency in exchange for their testimony?), and

- any statements that the informant made in connection with the case.

Although the burden of proof is less strict than a Franks hearing, the defense still must cast doubt as to the truthfulness of the informant’s testimony. If you accomplish this, the court will conduct an in camera hearing to determine if the statements are material.25

If the statements are material, the court will redact (or remove) any information that may disclose the informant’s identity before it provides you with the

- affidavit or

- supporting document(s).26

If, during this hearing, you discover that the informant is a material witness to your guilt or innocence, you would move to disclose their identity at a Hobbs hearing.

Hobbs hearings

At a Hobbes hearing, the defense asks the judge to reveal the identity of the confidential informant upon whose information the California search warrant got issued.

When the entire affidavit has been sealed to protect the informant’s identity, it may be too difficult even to qualify for a Luttenberger hearing. When this is the case, the court must conduct an in-camera hearing upon receipt of your motion to traverse or quash the California search warrant.27

Unless the prosecutor agrees, the hearing takes place without you or your criminal defense attorney.28 During this closed hearing, the judge must decide

- whether to maintain the confidentiality of the informant, and

- whether the affidavit has been properly sealed.29

If the court believes that the affidavit was properly sealed but does not believe that the information contained in it was false or misleading, it will simply deny your motion.30

If, however, the court believes that you may succeed in your motion, it will first give the prosecution the opportunity to disclose their informant or have the case dismissed if the judge rules in your favor.31

In our experience, the prosecution will generally dismiss the case before revealing or “burning” the police informant.

5. How are the police allowed to execute a warrant?

The contents of a California search warrant must be described with reasonable particularity.32

Simply put, “reasonable particularity” means that the warrant should be so clear that nothing is left to the officer’s discretion when executing it.33 This applies to both

- the place to be searched, and

- the person/property to be seized.34

This means that a search warrant must be executed according to the exact details contained in the warrant35 – warrants that are clear in their descriptions will be upheld and those that are unduly vague will not.

The following are some examples taken from actual California court cases regarding law enforcement agency searches:36

Descriptions that were found not to be sufficiently clear —

- “all of the financial records”

- “other evidence”

- “stolen property”

- “certain personal property used as a means of committing larceny“

Items that were described with reasonable particularity —

- “personal property tending to identify the person in control”

- “bookmaking paraphernalia”

- “illegal deer meat and/or elk meat, etc.”

The more specific the language, the more likely the California search warrant will be upheld.

Time of execution

A California search warrant must be executed within ten (10) days of its issuance. If it has not been executed within that timeframe, it becomes void.37

If the warrant expires, it may be reissued as long as the judge still believes there is probable cause to support it.38 It, therefore, follows that if the probable cause that existed at the time of the original issuance is no longer relevant, the judge will not reissue the warrant.

There are also restrictions on what time of day a warrant may be executed. As a general rule, a search warrant may only be executed between 7 a.m. and 10 p.m. If, however, the judge finds good cause, they may authorize service at any time of the day or night.39

“Good cause” means that there is a factual basis for believing that a nighttime intrusion would be justified based on exigent circumstances.40 If, for example, you have several outstanding warrants, service will be authorized whenever possible.

When establishing good cause, the judge must consider both

- public safety and

- the safety of the officers serving the warrant.42

See our article on What happens after a search warrant is executed?

With respect to seized property…

The officer must provide a detailed receipt for any property that they seized during the search. The officer must leave the receipt with

- the person from whom they took the property,

- the person who possessed the property, or

- where they found the property if it was taken without anyone being present.42

Once taken, the officer must keep the property in police custody until they present it to the court.43

All that said, the police are not permitted to search and seize anyone or anything until they have announced their presence.

6. What is the knock and announce rule?

Before an officer may execute a California search warrant at your home (or possibly your business44), the officer must

- knock on the door,

- announce themself as a law enforcement officer,

- inform you that they have a search warrant, and

- give you enough time to open the door.45

It should be noted that the third requirement may technically be completed after you open the door but in either event must be before the officer enters the home.46

There is no steadfast rule as to exactly how these knock-notice (also referred to as the “knock and announce rule“) requirements should be executed. So in order to determine whether the executing officers have legally fulfilled their duties under California’s knock-notice law, the court will look for substantial compliance.

“Substantial compliance,” in its simplest terms, means that the policies underlying the knock and announce requirements are achieved under the circumstances.47 These policies include:

- protecting a homeowner’s privacy,

- protecting innocent people on the premises,

- preventing situations that may otherwise encourage a violent confrontation between a homeowner and those who enter their home without notice, and

- protecting the police from a startled or fearful homeowner/occupant.48

The knock-notice rules and the policies behind them are to ensure that if and when the police force entry into your home, it is only because you knowingly refused their entry.

Forced entry

When is it okay for law enforcement officers to enter a home without permission? After their entry has been refused.

If you (as the owner or occupant) refuse to

- open the door for the officers, or

- permit them into your home,

the police may break in through a door, window, or any other part of the house to execute the California search warrant.49 The same holds true if no one is home.50

Assuming you are home, there must be some evidence of a refusal before the police may legally force their way in. This is most typically evidenced by either

- an unreasonable delay in responding to the officers’ request to enter51 (which must be determined based on the facts of the specific case), or

- an outright refusal where you tell the police that you will not open the door.52

Some examples of situations where California courts have held that unlawful forced entries took place include:

- where knock-notice requirements were not fulfilled (for example, although the officer announced their presence, they did not state their purpose)53

- where the officer simultaneously announced their presence and forced entry without giving the homeowner the opportunity to comply or refuse54

- where the forceful entry was only 20 seconds after the officers otherwise complied with the knock-notice rules.55

- where knock and announce rules were not followed when the officer entered the home to secure it while the warrant was being obtained56

- where the officer announced that they were a police officer (without stating his purpose) and only after they had already forced entry.57

There are, of course, certain times when officers are permitted to execute a California search warrant by forcing their entry even without complying with the knock-notice requirements.

Exceptions to California’s knock-notice rule

The following are some of the most common exceptions to the knock and announce requirement:

- consent (if you consent to the officer’s entry, the officer does not need to proceed with knock-notice requirements)58

- public places (knock and announce rules are designed to respect your privacy in your home – there is no similar privacy right in a public place)59

- exigent circumstances (“exigent circumstances” basically mean that “time is of the essence”).

When exigent circumstances are present, the knock-notice requirements may be waived. This is most typically the case where police suspect that those inside the home

- may arm themselves, or

- destroy the drugs

if they first knock and announce their presence.

There is no blanket exception for exigent circumstances, as each case must be independently evaluated.60 The judge will likely excuse a knock-notice violation

“[I]f the specific facts known to the officer before his entry are sufficient to support his good faith belief that compliance will increase his peril, frustrate the arrest, or permit the destruction of evidence[.]”61

Absent one of these recognized exceptions, a knock-notice violation may render any subsequent search and seizure unreasonable, and therefore, illegal.62 When a search and/or seizure is illegal, the prosecution will be prevented from using any of the seized evidence against you at trial.63

7. What is a motion to suppress evidence?

The most common challenge to a search warrant lies in a California Penal Code 1538.5 PC motion to suppress evidence. This motion may be filed if you wish to

- recover seized evidence, or

- exclude seized evidence from your trial.

A California criminal defense attorney may file an “unreasonable search and seizure” Penal Code 1538.5 motion based on any of the following facts:

- that the California search warrant was insufficient on its face (this issue could also be raised in a motion to quash the warrant)

- that there was no probable cause to issue the search warrant (raised in either a motion to quash or traverse)

- that the seized property or other evidence was not specifically described in the search warrant (for example, the officers seized non-deadly weapons when the warrant specifically said deadly weapons)

- that the execution of the search warrant was illegal.64

If any part of the search was unlawful, any discovered evidence will typically be excluded under this section. As John Murray, one of Ventura’s top criminal defense attorneys, puts it,

“This ‘exclusionary rule’ is one of the most powerful defenses available.”

If your motion is granted, the prosecution will be prohibited from “using” the seized evidence against you at trial. A victory on this motion will often lead the prosecutor to dismiss (or at the very least significantly reduce) your charge(s).

Legal References:

- Collins v. Lean, (1885) 68 Cal.284, 288 (“Under article 4 of the amendments to the U.S. constitution … , it is provided that no search-warrant shall issue but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the person or things to be seized. To the same effect is section 19 of article 1 of our state constitution. As we read those instruments we do not find existent therein any prohibition against the issuance of a search warrant of the person of an individual in a proper case. Therefore, subject to the limitations of those constitutions, and subject also to the conditions that body may itself have prescribed, it is within the power of our state legislature to authorize the issuance of such a warrant. And this power it has exercised by the enactment in the Penal Code of sections 1523 to 1542 inclusive.”)

- California Penal Code 1523 — Definition. (“A search warrant is an order in writing, in the name of the people, signed by a magistrate, directed to a peace officer, commanding him or her to search for a person or persons, a thing or things, or personal property, and, in the case of a thing or things or personal property, bring the same before the magistrate.”)

- See same. (“A search warrant is an order in writing, in the name of the people, signed by a magistrate….”)

- People of the State of California v. Escamilla, (1976) 65 Cal.App.3d 558, 562 (“Adverting to the responsibility devolving upon a magistrate in the issuance of a search warrant, it has been said that “… an issuing magistrate must meet two tests. He must be neutral and detached, and he must be capable of determining whether probable cause exists for the requested arrest or search.” ( Shadwick v. City of Tampa (1972) 407 U.S. 345, 350.) The goal is to require an informed and deliberate review of the circumstances by one who is removed from “‘… the often competitive enterprise of ferreting out crime”‘.”)

- California Penal Code 1525 — Issuance; probable cause; supporting affidavits; contents of application. (“A search warrant cannot be issued but upon probable cause, supported by affidavit, naming or describing the person to be searched or searched for, and particularly describing the property, thing, or things and the place to be searched.”)

- California Penal Code 1528 — Issuance; magistrate satisfied as to grounds; formalities; command; duplicate original warrant. (“(a) If the magistrate is thereupon satisfied of the existence of the grounds of the application, or that there is probable cause to believe their existence, he or she must issue a search warrant, signed by him or her with his or her name of office, to a peace officer in his or her county, commanding him or her forthwith to search the person or place named for the property or things or person or persons specified, and to retain the property or things in his or her custody subject to order of the court as provided by [California Penal Code] Section 1536.”)

- California Penal Code 1524 — Issuance; grounds; special master. See, for example, People v. Ng (2022) ; People v. Wilson (2021) .

- See same — California Penal Code 1524(c). See also California Penal Code 1525 — Issuance; probable cause; supporting affidavits; contents of application. (“The application shall specify when applicable, that the place to be searched is in the possession or under the control of an attorney, physician, psychotherapist or clergyman.”)

- California Penal Code 1525 — Issuance; probable cause; supporting affidavits; contents of application. (“A search warrant cannot be issued but upon probable cause, supported by affidavit, naming or describing the person to be searched or searched for, and particularly describing the property, thing, or things and the place to be searched.”)

- People v. Bell, (1996) 45 Cal.App.4th 1030, 1054 (“Appellants readily agree Penal Code section 1526, subdivision (a), states: “The magistrate, before issuing the warrant, may examine on oath the person seeking the warrant and any witnesses the person may produce,” (italics added) and that no section of the code requires the person seeking a search warrant be a peace officer. Appellants note, however, that Penal Code section 1523 defines a search warrant as “an order in writing, in the name of the people, signed by a magistrate, directed to a peace officer, commanding him to search for personal property.” Appellants further note other sections of the code dealing with the execution of the warrant all mention peace officers or officers and make no reference to unsworn persons. (Pen.Code 1528, subd. (a), 1530, 1535.) Appellants contend these references to peace officers evidence an intent not only that officers must execute warrants, but that only they may seek them. We have found no case suggesting such an intent. While the reasons for requiring a search warrant only be served by a peace officer are obvious, there seems no reason why seeking one should be confined to peace officers instead of unsworn members of law enforcement. Seemingly the person who seeks the warrant or provides their affidavit should be the person with most direct knowledge of the facts supporting probable cause. We see no reason why a deputy district attorney or an unsworn investigator for a police department, for example, cannot seek a search warrant.”)

- California Penal Code 1526 — Issuance; examination of complainant and witnesses; taking and subscribing affidavits; transcribed statements or oath made using telephone and facsimile transmission equipment in lieu of written affidavit.

- California Penal Code 1527 — Affidavits; contents. (“The affidavit or affidavits must set forth the facts tending to establish the grounds of the application, or probable cause for believing that they exist.”)

- People v. Aguilar, (1966) 240 Cal.App.2d 502, 508 (“In Aguilar v. Texas, supra (1964) 378 U.S. 108, 114 [84 S.Ct. 1509, 1514, 12 L.Ed.2d 723, 729], the United States Supreme Court said: “Although an affidavit may be based on hearsay information and need not reflect the direct personal observations of the affiant, the magistrate must be informed of some of the underlying circumstances from which the informant concluded that the narcotics were where he claimed they were, …” … And in United States v. Ventresca, supra (1965) 380 U.S. 102, 108 [85 S.Ct. 741, 746, 13 L.Ed.2d 684, 689], the court repeated that same admonition, saying: “This is not to say that probable cause can be made out by affidavits which are purely conclusory, stating only the affiant’s or an informer’s belief that probable cause exists without detailing any of the ‘underlying circumstances’ upon which that belief is based. Recital of some of the underlying circumstances in the affidavit is essential if the magistrate is to perform his detached function and not serve merely as a rubber stamp for the police.”FN6”)

- See same at 508. (“‘Although information provided by an anonymous informer is relevant on the issue of reasonable cause, in the absence of some pressing emergency, an arrest may not be based solely on such information, and evidence must be presented to the court that would justify the conclusion that reliance on the information was reasonable. In some cases the identity of, or past experience with, the informer may provide such evidence, and in others it may be supplied by similar information from other sources or by the personal observations of the police.’”)

- See same at 507. (“Although in cases where a search is based on an arrest without a warrant, the officer, if he relies for probable cause on information obtained from an informant, must, on request of defendant, disclose the name of the informant or the testimony will be stricken (Priestly v. Superior Court, supra (1958) 50 Cal.2d 812), the rule is different in cases where the search is made under a warrant. In warrant cases, it is the issuing magistrate who must be convinced of probable cause. If the magistrate thinks it necessary, he may require disclosure of the informant’s name, or may require that the informant be brought before him for the purpose of making a deposition under section 1526 of the [California] Penal Code. But, since it is the magistrate who determines reliability of the informant, the option to require disclosure is with him and his implied finding of reliability is conclusive on that point.”)

- People v. Martinez, (2005) 132 Cal.App.4th 233, 240 (“It is settled that “all or any part of a search warrant affidavit may be sealed if necessary to implement the privilege [under [California] Evidence Code section 1041] and protect the identity of a confidential informant.” ( Hobbs, supra, 7 Cal.4th at p. 971, 30 Cal.Rptr.2d 651, 873 P.2d 1246; Evid.Code, 1042, subd. (b).)”). See also Electronic Frontier Foundation, Inc. v. Superior Court (Court of Appeal of California, Fourth Appellate District, Division Two, 2022) 83 Cal. App. 5th 407.

- See same. (“Consequently, courts are not required to disclose “the identity of an informant who has supplied probable cause for the issuance of a search warrant … where such disclosure is sought merely to aid in attacking probable cause.”)

- Franks v. Delaware, (1978) 438 U.S. 154, 155 (“In the present case the Supreme Court of Delaware held, as a matter of first impression for it, that a defendant under no circumstances may so challenge the veracity of a sworn statement used by police to procure a search warrant. We reverse, and we hold that, where the defendant makes a substantial preliminary showing that a false statement knowingly and intentionally, or with reckless disregard for the truth, was included by the affiant in the warrant affidavit, and if the allegedly false statement is necessary to the finding of probable cause, the Fourth Amendment requires that a hearing be held at the defendant’s request.”)

- People v. Lewis, (2006) 39 Cal.4th 970, 988 (“…”a defendant has a limited right to challenge the veracity of statements contained in an affidavit of probable cause made in support of the issuance of a search warrant…. [T]he lower court must conduct an evidentiary hearing [only if] a defendant makes a substantial showing that (1) the affidavit contains statements that are deliberately false or were made in reckless disregard of the truth; and (2) the affidavit’s remaining contents, after the false statements are excised, are insufficient to support a finding of probable cause…Innocent or negligent misrepresentations will not defeat a warrant.”)

- People v. Luttenberger, (1990) 50 Cal.3d 1, 15 (“The Crabb court stated that for purposes of the issues presented, it would treat a claim of material omissions similarly to the Franks-type problem of material misstatements…This treatment is acceptable.”)

- Franks v. Delaware, (1978) 438 U.S. 154, 155 (“…where the defendant makes a substantial preliminary showing that a false statement knowingly and intentionally, or with reckless disregard for the truth, was included by the affiant in the warrant affidavit, and if the allegedly false statement is necessary to the finding of probable cause, the Fourth Amendment requires that a hearing be held at the defendant’s request.”)

- People v. Brown, (Court of Appeal, 1989) 207 Cal.App.3d 1541, 1548 (“Here, because the court elected to conduct an in camera hearing to determine the truth or falsity of the information given to Meyer, we assume the court believed Brown’s affidavits raised sufficient questions to warrant further inquiry. The court correctly questioned the informants in camera to determine what they had told Meyer. As a result of this inquiry the court was satisfied that the preliminary showing was rebutted and the officer’s affidavit was not materially false. It therefore concluded there was no need for an evidentiary hearing. Through this procedure the court complied with [California] Evidence Code section 1042, subdivision (d), and Franks v. Delaware.”)

- See Franks, endnote 17 above at 156. (“In the event that at that hearing the allegation of perjury or reckless disregard is established by the defendant by a preponderance of the evidence, and, with the affidavit’s false material set to one side, the affidavit’s remaining content is insufficient to establish probable cause, the search warrant must be voided and the fruits of the search excluded to the same extent as if probable cause was lacking on the face of the affidavit.”)

- People v. Hobbs, (1994) 7 Cal.4th 948, 959 (“In contrast to the situation where the defendant is seeking to discover whether a confidential informant is a material witness on the issue of guilt or innocence, where the defendant merely seeks to discover the informant’s identity in connection with a challenge to the legality of a search based on information furnished by the informant, a critical distinction is drawn in the case law between searches conducted pursuant to warrant and warrantless searches. It has long been the rule in California that the identity of an informant who has supplied probable cause for the issuance of a search warrant need not be disclosed where such disclosure is sought merely to aid in attacking probable cause.”)

- People v. Luttenberger, (1990) 50 Cal.3d 1, 21 (“To justify in camera review and discovery, preliminary to a subfacial challenge to a search warrant, a defendant must offer evidence casting some reasonable doubt on the veracity of material statements made by the affiant.”)

- See same at 19. (“…to allow the court to determine materiality and delete information that might identify the informant, may impose a lesser burden on trial courts than such an in camera evidentiary hearing.”)

- See Hobbs, endnote 24 above at 972. (“In contrast to the situation in which the informant’s privilege is asserted merely to avoid disclosure of the confidential informant’s name, where, as here, all or a major portion of the search warrant affidavit has been sealed in order to preserve the confidentiality of the informant’s identity, a defendant cannot reasonably be expected to make even the “preliminary showing” required for an in camera hearing under Luttenberger. For this reason, where the defendant has made a motion to traverse the warrant under such circumstances, the court should treat the matter as if the defendant has made the requisite preliminary showing required under this court’s holding in Luttenberger. On a properly noticed motion by the defense seeking to quash or traverse the search warrant, the lower court should conduct an in camera hearing pursuant to the guidelines set forth in section 915, subdivision (b), and this court’s opinion in Luttenberger, supra, 50 Cal.3d at pages 20-24, 265 Cal.Rptr. 690, 784 P.2d 633.”)

- See same at 961. (“…where the defendant demands disclosure of the identity of a confidential informant “on the ground the informant is a material witness on the issue of guilt” (italics added), a hearing must be held, and it must be conducted in camera and outside the presence of the defendant and his counsel if the prosecution so requests.”)

- See same. (“It must first be determined whether sufficient grounds exist for maintaining the confidentiality of the informant’s identity. It should then be determined whether the entirety of the affidavit or any major portion thereof is properly sealed, i.e., whether the extent of the sealing is necessary to avoid revealing the informant’s identity.”)

- See same at 974. (“If the trial court determines that the materials and testimony before it do not support defendant’s charges of material misrepresentation, the court should simply report this conclusion to the defendant and enter an order denying the motion to traverse.”)

- See same. (“If, on the other hand, the court determines there is a reasonable probability that defendant would prevail on the motion to traverse-i.e., a reasonable probability, based on the court’s in camera examination of all the relevant materials, that the affidavit includes a false statement or statements made knowingly and intentionally, or with reckless disregard for the truth, which is material to the finding of probable cause ( Franks, supra, 438 U.S. at pp. 155-156, 98 S.Ct. at pp. 2676-2677)-the district attorney must be afforded the option of consenting to disclosure of the sealed materials, in which case the motion to traverse can then proceed to decision with the benefit of this additional evidence, and a further evidentiary hearing if necessary ( Seibel, supra, 219 Cal.App.3d at p. 1300, 269 Cal.Rptr. 313; People v. Brown (1989) 207 Cal.App.3d 1541, 1548, 256 Cal.Rptr. 11), or, alternatively, suffer the entry of an adverse order on the motion to traverse.”)

- Constitution of the United States Amendment IV — Search and Seizure. (“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”) Almost identical language is duplicated in California Constitution Article I, section 13 and California Penal Code 1525 (endnote 7 above).

- Marron v. U.S., (1927) 275 U.S. 192, 196 (“The requirement that warrants shall particularly describe the things to be seized makes general searches under them impossible and prevents the seizure of one thing under a warrant describing another. As to what is to be taken, nothing is left to the discretion of the officer executing the warrant.”)

- People v. Smith, (1994) 21 Cal.App.4th 942, 948 (“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable seizures and searches may not be violated; and a warrant may not issue except on probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons and things to be seized.” (Cal. Const., art. I, 13, italics added; see also Pen. Code, 1525, 1529.) The italicized portions plainly indicate that the particularity clause is, in realty, two clauses. The first is directed to the place or places to be searched. The second is directed to the persons and/or things to be seized.”)

- Thompson v. Superior Court, (1977) 70 Cal.App.3d 101, 112 (“In summary, we hold that in determining the property to be seized pursuant to a warrant, we are confined to the four corners of the warrant.”)

- People v. Superior Court (Williams), (1978) 77 Cal.App.3d 69, 77 (Overruled on different grounds) (“We are required by the Constitution to determine if the affidavit and the warrant describe the property with particularity, i.e., place a meaningful restriction on the objects to be seized. Whether the description in the warrant is sufficiently definite is a question of law on which an appellate court makes an independent judgment. ( Thompson v. Superior Court, supra., 70 Cal.App.3d 101, 108.) In determining whether a meaningful restriction has been placed on the objects to be seized, the courts have held as follows: “All of the financial records ” is insufficient ( Burrows v. Superior Court (1974) 13 Cal.3d 238, 249; “any and all other business records and paraphernalia” connected with the business being searched is insufficient ( Aday v. Superior Court (1961) 55 Cal.2d 789, 795-796; “certain personal property used as a means of committing … larceny” is insufficient ( People v. Mayen (1922) 188 Cal. 237, 242 [205 P. 435, 24 A.L.R. 1383]), overruled on different grounds, People v. Cahan (1955) 44 Cal.2d 434, 445; personal property “tending to identify the person in control” is sufficient ( People v. Howard (1976) 55 Cal.App.3d 373, 376; stolen merchandise is insufficient when an inventory could have been provided ( Lockridge v. Superior Court (1969) 275 Cal.App.2d 612, 625; “bank statements, checkbooks and other evidences of indebtedness” too broad ( Griffin v. Superior Court (1972) 26 Cal.App.3d 672, 695; “bookmaking paraphernalia” held sufficient ( People v. Barthel (1965) 231 Cal.App.2d 827, 832; “illegal deer meat and/or elk meat, etc.” is sufficient ( Dunn v. Municipal Court (1963) 220 Cal.App.2d 858, 868; “other evidence” is insufficient ( Stern v. Superior Court (1946) 76 Cal.App.2d 772, 784; “stolen property” insufficient ( Thompson v. Superior Court, supra., 70 Cal.App.3d 101, 105); “… nothing is left to the discretion of the officer executing the warrant” ( Marron v. United States (1927) 275 U.S. 192, 196 [72 L.Ed. 231, 237, 48 S.Ct. 74]).”)

- California Penal Code 1534 — Time limit for execution and return. (“(a) A search warrant shall be executed and returned within 10 days after date of issuance. A warrant executed within the 10-day period shall be deemed to have been timely executed and no further showing of timeliness need be made. After the expiration of 10 days, the warrant, unless executed, is void. The documents and records of the court relating to the warrant need not be open to the public until the execution and return of the warrant or the expiration of the 10-day period after issuance. Thereafter, if the warrant has been executed, the documents and records shall be open to the public as a judicial record. (b) If a duplicate original search warrant has been executed, the peace officer who executed the warrant shall enter the exact time of its execution on its face. (c) A search warrant may be made returnable before the issuing magistrate or his court.”)

- People v. Brocard, (1985) 170 Cal.App.3d 239, 243 (“The case of People v. Sanchez (1972) 24 Cal.App.3d 664 lends partial support to our conclusion a search warrant may be reissued as long as there is no staleness problem. The Sanchez court held, “[a]lthough there is no statutory authority for the revalidation and reissuance of a search warrant, we see no good reason why, within 10 days of the original issuance, an officer should be precluded from presenting supplemental information to the issuing magistrate, nor why the magistrate, based thereon, should not by appropriate endorsement revalidate and reissue the original warrant rather than issue an entirely new warrant. [Citation.]” (Italics added.) ( Id., at p. 682.) Admittedly Sanchez only upholds reissuance within 10 days of the original issuance. However, even the Sanchez rationale could potentially result in execution of a reissued warrant more than 10 days after the original issuance.) Finally, we do not find it absolutely necessary there be new information to support reissuance of a search warrant. In cases like this one, where the original affidavit contained recent information showing ongoing criminal activity, that affidavit alone may be sufficient to support a probable cause finding at the time of reissuance.”)

- California Penal Code 1533 — Direction as to time for search; grounds for search at night; good cause. (“Upon a showing of good cause, the magistrate may, in his or her discretion, insert a direction in a search warrant that it may be served at any time of the day or night. In the absence of such a direction, the warrant shall be served only between the hours of 7 a.m. and 10 p.m.”)

- People v. Ramirez, (1988) 202 Cal.App.3d 425, 427 (“In the related context of nighttime search warrants, our Supreme Court recently defined the good cause rule as requiring “‘only some factual basis for a prudent conclusion that the greater intrusiveness of a nighttime search is justified by the exigencies of the situation. …”)

- See California Penal Code 1533 above. (“When establishing “good cause” under this section, the magistrate shall consider the safety of the peace officers serving the warrant and the safety of the public as a valid basis for nighttime endorsements.”)

- California Penal Code 1535 — Receipt for property taken. (“When the officer takes property under the warrant, he must give a receipt for the property taken (specifying it in detail) to the person from whom it was taken by him, or in whose possession it was found; or, in the absence of any person, he must leave it in the place where he found the property.”)

- California Penal Code 1536 — Disposition of property taken; retention subject to order of court in which offense triable. (“All property or things taken on a warrant must be retained by the officer in his custody, subject to the order of the court to which he is required to return the proceedings before him, or of any other court in which the offense in respect to which the property or things taken is triable.”)

- People v. Pompa, (1989) 212 Cal.App.3d 1308, 1312 (“Livermore [(1973) 30 Cal.App.3d 1073] involved the search of a residence. Here, the entry was to an office which was part of a business establishment, premises entitled to a lesser expectation of privacy under the Fourth Amendment than that protection afforded a home. ( People v. Lee (1986) 186 Cal.App.3d 743, 750, 231 Cal.Rptr. 45; United States v. Agrusa (8th Cir.1976) 541 F.2d 690, 700; United States v. Clayborne (10th Cir.1978) 584 F.2d 346.) Thus to the extent the knock-notice rule applies to business premises, it has less force than when applied to dwellings.”)

- People v. Ramsey, (1988) 203 Cal.App.3d 671, 679 (“[California Penal Code] Section 1531 provides: “The officer may break open any outer or inner door or window of a house, or any part of a house, or anything therein, to execute the warrant, if, after notice of his authority and purpose, he is refused admittance.” Under this section, police officers are required: “(1) to knock or utilize other means reasonably calculated to give adequate notice of their presence to the occupants, (2) to identify themselves as police officers, and (3) to explain the purpose of their demand for admittance.””)

- People v. Mays, (1998) 67 Cal.App.4th 969, 972 (“In support of his suppression motion, Mays argued, and the court agreed, the officers had not announced their purpose until after Riley opened the front door in response to their knocks. The People contend the court erred in finding the officers’ announcement of purpose must precede the opening of the door in order to satisfy constitutional and statutory knock-notice requirements. We agree.”)

- See same. (“The essential inquiry is whether under the circumstances the policies underlying the knock-notice requirements were served.”)

- People v. Macioce, (1987) 197 Cal.App.3d 262, 271 (“The purposes and policies supporting the ‘knock-notice’ rules are fourfold: (1) the protection of the privacy of the individual in his home; (2) the protection of innocent persons present on the premises; (3) the prevention of situations which are conducive to violent confrontations between the occupant and individuals who enter his home without proper notice; and (4) the protection of police who might be injured by a startled and fearful householder.”)

- California Penal Code 1531 — Execution; authority to break in after admittance refused. (“The officer may break open any outer or inner door or window of a house, or any part of a house, or anything therein, to execute the warrant, if, after notice of his authority and purpose, he is refused admittance.”)

- Hart v. Superior Court, (1971) 21 Cal.App.3d 496, 504 (“Prima facie, the statute [California Penal Code 1531] mandates that in executing a search warrant an officer must first determine whether anyone is present within the premises to be searched. If an affirmative determination is made, the officer must request admittance by giving notice of his authority and purpose. If, however, it is determined that no one is present and if that determination is supported by the evidence, the notice of authority and purpose requirement is not essential to the validity of the entry and subsequent search.”)

- People v. Peterson, (1973) 9 Cal.3d 717, 723 (“Officer Kalm testified that he knocked several times, waited approximately one minute during which interval he observed two persons seated only a short distance inside the screen door. They gave no indication that they intended to respond. Such a delay with notice of the officer’s presence, would reasonably constitute a rejection of the officer’s demands.”) See also Jeter, endnote 38 above at 937. (“Thus, in both Elder and Gallo the police had first-hand concrete knowledge that someone was in the residence and was awake: in Elder the police had the residents on the phone, and in Gallo they had them in view. With such information it was not unreasonable for the officers in the Elder and Gallo situations to conclude that a failure to respond to their knocking and announcing of purpose was a refusal of permission to enter.”)

- People v. Cressey, (1970) 2 Cal.3d 836, 840 (“The officer inquired, “Jesse Cressey?” and defendant responded, “Yes.” Properly explaining his purpose, the officer said, “I have two warrants for your arrest charging you with failure to provide, and a traffic warrant. Open the door. You’re under arrest.” The defendant answered, “I’m not going to open the door. You don’t have any failure to provide warrant for me. I sent my ex-wife one hundred dollars last week.” Although the officer did not at that time possess the warrant, he informed the defendant again that the police had such a warrant and ordered defendant to submit to arrest and open the door or he would force entry.FN4 Defendant declared: “Go ahead because I’m not going to open the door. If you break it down, I’ll sue the City.””)

- People v. Cain, (1968) 261 Cal.App.2d 383, 391 (“The court held that the failure of the officers to explain their purpose and demand admittance, as required by [California] Penal Code section 844, was fatal to the legality of the arrest. (Id. at 310, 66 Cal.Rptr. 1, 437 P.2d 489.) The mere announcement to the girl that they were police officers was not sufficient compliance with the statute. ‘That section requires that an officer explain his purpose before demanding admittance, not merely that he identify himself as an officer.’ (Id. at 310, 66 Cal.Rptr. 1, 3, 437 P.2d 489, 491.) It is unchallenged in the case before us that Cozzalio did not fully comply with [California] Penal Code section 1531. He did not announce his purpose, nor was he refused admittance. (This refusal is required by Penal Code section 1531, but not by Penal Code section 844.) The Supreme Court has clearly established that variance from Penal Code section 844 and 1531 will be tolerated only in the exceptional situation. As shown above, this case is not the exceptional situation.”)

- People v. Benjamin, (1969) 71 Cal.2d 296, 297 (“…for even if we assume that the officer’s ‘yell’ was an effort on his part to give ‘notice of his authority and purpose,’ it appears that that ‘yell’ was simultaneous with and a part of the entry and that the occupant of the apartment was given no opportunity to grant or refuse admittance. Finally, the record herein provides no basis for concluding that the officer was excused from compliance with the section under the common law exceptions to the rule of announcement. ‘Our decision in People v. Gastelo, Supra, 67 Cal.2d 586, 63 Cal.Rptr. 10, 432 P.2d 706, clearly forecloses the propriety of noncompliance with section 844 or its counterpart section 1531 when such noncompliance is based solely upon an officer’s general experience relative to the disposability of the king of evidence sought and the propensity of offenders to effect disposal.’”)

- Jeter v. Superior Court, (1983) 138 Cal.App.3d 934, 936 (“Testimony at the preliminary hearing revealed that Officer Munoz, accompanied by four other police officers, arrived at 1224 Fruitvale Avenue about 11 a.m. on July 30, 1981, to serve a search warrant. No surveillance of the premises was undertaken. The officers drove up and parked. Then Officer Munoz knocked on the front door and yelled, “police officers, we have a search warrant.” He waited a “few seconds” and knocked and yelled again. After waiting “five or ten seconds”, he turned the handle and pushed open the door. Upon entering the residence he saw petitioner and Mr. Brown in a sleeping loft: petitioner was sitting on the bed unclad and Brown was asleep.”) The court pointed out that 20 seconds isn’t a steadfast rule but specifically applied to this case. In cases where the police knew that people were in the house and that criminal activity was taking place, a 20-second delay was permissible.

- Machado v. Superior Court, (1975) 45 Cal.App.3d 316, 320 (“Two recent cases have considered the applicability of [California Penal Code] sections 844 and 1531 to situations where a house was secured pending receipt of a search warrant. (People v. Freeny, 37 Cal.App.3d 20, 112 Cal.Rptr. 33; Ferdin v. Superior Court, 36 Cal.App.3d 774, 112 Cal.Rptr. 66.) The clear implication in both cases is that the courts felt that the knock-and-notice requirements had to be complied with when officers were entering to secure a house pending the arrival of a search warrant. Ferdin specifically recognized that the time the danger of violent confrontation exists is when the entry is made to secure the house and not when the warrant later arrives.”)

- Parsley v. Superior Court, (1973) 9 Cal.3d 934, 938 (“FN3 Once inside the dwelling, the officer informed defendant Parsley, “We’re police officers.” This statement does not satisfy [California Penal Code] section 1531 because (1) it was made inside the house, and (2) it did not include a statement of purpose.”)

- People v. Byrd, (1974) 38 Cal.App.3d 941, 9 (“The trial court found that the evidence showed that Ms. Moser asked Mr. Benner to come in. [California Penal Code] Sections 844 and 1531 are inapplicable under such circumstances. “Since the officers’ entry here was consented to by persons present inside the house, the section does not apply.”)

- People v. Lovett, (1978) 82 Cal.App.3d 527, 531 (“Although the People cite no case to the effect that section 1531 of the [California]Penal Code does not apply where the premises to be searched are a store open to the public, a contrary rule would make little sense. None of the purposes of the statute would be advanced by requiring police officers to state their “authority and purpose” before crossing the threshold of a store into which the general public has been invited to enter.”)

- People v. Scott, (1968) 259 Cal.App.2d 268, 279 (“Strict compliance with the requirements of [California Penal Code] section 1531 is excused when the circumstances reasonably require it. (People v. Barthel (1965) 231 Cal.App.2d 827, 832; People v. Villanueva (1963) 220 Cal.App.2d 443, 447. An officer executing a warrant authorizing a search for narcotics does not, because the contraband is easily disposed of, enjoy a blanket authorization to make an unannounced forcible entry. (People v. Gastelo (1967) 67 Cal.2d 586) But here the officer had reason to believe that although appellant was outside in the car other parties were within the house. It was not unreasonable for him to believe that appellant sounded the car horn for the purpose of signaling someone inside the house to destroy the contraband and thus frustrate the search which had been authorized by the warrant. Under these circumstances it was proper for the officer to make immediate entry.”)

- People v. Murphy, (2005) 37 Cal.4th 490, 497 (“…strict compliance with the knock-notice rule is excused “if the specific facts known to the officer before his entry are sufficient to support his good faith belief that compliance will increase his peril, frustrate the arrest, or permit the destruction of evidence.”)

- People v. Pacheco, (1972) 27 Cal.App.3d 70, 77 (“An entry of a house, in violation of the aforementioned section, renders any following search and seizure unreasonable within the purview of the Fourth Amendment.”)

- People v. Rodriquez, (1969) 274 Cal.App.2d 770, 773 (“…an unannounced entry by the police into a house, contrary to [California] Penal Code section 1531, is illegal and that evidence adduced therefrom is inadmissible as the product of an unreasonable search.”)

- California Penal Code section 1538.5 — Motion to return property or suppress evidence.

To Learn More…. Read MORE Below and click the links Below

Abuse & Neglect – The Mandated Reporters (Police, D.A & Medical & the Bad Actors)

Mandated Reporter Laws – Nurses, District Attorney’s, and Police should listen up

If You Would Like to Learn More About: The California Mandated Reporting LawClick Here

To Read the Penal Code § 11164-11166 – Child Abuse or Neglect Reporting Act – California Penal Code 11164-11166Article 2.5. (CANRA) Click Here

Mandated Reporter formMandated ReporterFORM SS 8572.pdf – The Child Abuse

ALL POLICE CHIEFS, SHERIFFS AND COUNTY WELFARE DEPARTMENTS INFO BULLETIN:

Click Here Officers and DA’s for (Procedure to Follow)

It Only Takes a Minute to Make a Difference in the Life of a Child learn more below

You can learn more here California Child Abuse and Neglect Reporting Law its a PDF file

Learn More About True Threats Here below….

We also have the The Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) – 1st Amendment

CURRENT TEST = We also have the The ‘Brandenburg test’ for incitement to violence – 1st Amendment

We also have the The Incitement to Imminent Lawless Action Test– 1st Amendment

We also have the True Threats – Virginia v. Black is most comprehensive Supreme Court definition – 1st Amendment

We also have the Watts v. United States – True Threat Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Clear and Present Danger Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Gravity of the Evil Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Elonis v. United States (2015) – Threats – 1st Amendment

Learn More About What is Obscene…. be careful about education it may enlighten you

We also have the Miller v. California – 3 Prong Obscenity Test (Miller Test) – 1st Amendment

We also have the Obscenity and Pornography – 1st Amendment

Learn More About Police, The Government Officials and You….

$$ Retaliatory Arrests and Prosecution $$

Anti-SLAPP Law in California

Freedom of Assembly – Peaceful Assembly – 1st Amendment Right

Supreme Court sets higher bar for prosecuting threats under First Amendment 2023 SCOTUS

We also have the Brayshaw v. City of Tallahassee – 1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Publius v. Boyer-Vine –1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, Florida (2018) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Nieves v. Bartlett (2019) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Hartman v. Moore (2006) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

We also have the Reichle v. Howards (2012) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

Freedom of the Press – Flyers, Newspaper, Leaflets, Peaceful Assembly – 1$t Amendment – Learn More Here

Vermont’s Top Court Weighs: Are KKK Fliers – 1st Amendment Protected Speech

We also have the Insulting letters to politician’s home are constitutionally protected, unless they are ‘true threats’ – Letters to Politicians Homes – 1st Amendment

We also have the First Amendment Encyclopedia very comprehensive – 1st Amendment

Sanctions and Attorney Fee Recovery for Bad Actors

FAM § 3027.1 – Attorney’s Fees and Sanctions For False Child Abuse Allegations – Family Code 3027.1 – Click Here

FAM § 271 – Awarding Attorney Fees– Family Code 271 Family Court Sanction Click Here

Awarding Discovery Based Sanctions in Family Law Cases – Click Here

FAM § 2030 – Bringing Fairness & Fee Recovery – Click Here

Zamos v. Stroud – District Attorney Liable for Bad Faith Action – Click Here

Malicious Use of Vexatious Litigant – Vexatious Litigant Order Reversed

Mi$Conduct – Pro$ecutorial Mi$Conduct Prosecutor$

Attorney Rule$ of Engagement – Government (A.K.A. THE PRO$UCTOR) and Public/Private Attorney

What is a Fiduciary Duty; Breach of Fiduciary Duty

The Attorney’s Sworn Oath

Malicious Prosecution / Prosecutorial Misconduct – Know What it is!

New Supreme Court Ruling – makes it easier to sue police

Possible courses of action Prosecutorial Misconduct

Misconduct by Judges & Prosecutor – Rules of Professional Conduct

Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

Standards on Prosecutorial Investigations – Prosecutorial Investigations

Information On Prosecutorial Discretion

Why Judges, District Attorneys or Attorneys Must Sometimes Recuse Themselves

Fighting Discovery Abuse in Litigation – Forensic & Investigative Accounting – Click Here

Criminal Motions § 1:9 – Motion for Recusal of Prosecutor

Pen. Code, § 1424 – Recusal of Prosecutor

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

National District Attorneys Association puts out its standards

National Prosecution Standards – NDD can be found here

The Ethical Obligations of Prosecutors in Cases Involving Postconviction Claims of Innocence

ABA – Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

Prosecutor’s Duty Duty to Disclose Exculpatory Evidence Fordham Law Review PDF

Chapter 14 Disclosure of Exculpatory and Impeachment Information PDF

Mi$Conduct – Judicial Mi$Conduct Judge$

Prosecution Of Judges For Corrupt Practice$

Code of Conduct for United States Judge$

Disqualification of a Judge for Prejudice

Judicial Immunity from Civil and Criminal Liability

Recusal of Judge – CCP § 170.1 – Removal a Judge – How to Remove a Judge

l292 Disqualification of Judicial Officer – C.C.P. 170.6 Form

How to File a Complaint Against a Judge in California?

Commission on Judicial Performance – Judge Complaint Online Form

Why Judges, District Attorneys or Attorneys Must Sometimes Recuse Themselves

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

DUE PROCESS READS>>>>>>

Due Process vs Substantive Due Process learn more HERE

Understanding Due Process – This clause caused over 200 overturns in just DNA alone Click Here

Mathews v. Eldridge – Due Process – 5th & 14th Amendment Mathews Test – 3 Part Test– Amdt5.4.5.4.2 Mathews Test

“Unfriending” Evidence – 5th Amendment

At the Intersection of Technology and Law

We also have the Introducing TEXT & EMAIL Digital Evidence in California Courts – 1st Amendment

so if you are interested in learning about Introducing Digital Evidence in California State Courts

click here for SCOTUS rulings

Right to Travel freely – When the Government Obstructs Your Movement – 14th Amendment & 5th Amendment

What is Probable Cause? and.. How is Probable Cause Established?

Misuse of the Warrant System – California Penal Code § 170 – Crimes Against Public Justice

What Is Traversing a Warrant (a Franks Motion)?

Dwayne Furlow v. Jon Belmar – Police Warrant – Immunity Fail – 4th, 5th, & 14th Amendment

Obstruction of Justice and Abuse of Process

What Is Considered Obstruction of Justice in California?

Penal Code 135 PC – Destroying or Concealing Evidence

Penal Code 141 PC – Planting or Tampering with Evidence in California

Penal Code 142 PC – Peace Officer Refusing to Arrest or Receive Person Charged with Criminal Offense

Penal Code 182 PC – “Criminal Conspiracy” Laws & Penalties

Penal Code 664 PC – “Attempted Crimes” in California

Penal Code 32 PC – Accessory After the Fact

Penal Code 31 PC – Aiding and Abetting Laws

What is Abuse of Process?

What is a Due Process Violation? 4th & 14th Amendment

What’s the Difference between Abuse of Process, Malicious Prosecution and False Arrest?

Defeating Extortion and Abuse of Process in All Their Ugly Disguises

The Use and Abuse of Power by Prosecutors (Justice for All)

ARE PEOPLE LYING ON YOU?

CAN YOU PROVE IT? IF YES…. THEN YOU ARE IN LUCK!

Penal Code 118 PC – California Penalty of “Perjury” Law

Federal Perjury – Definition by Law

Penal Code 132 PC – Offering False Evidence

Penal Code 134 PC – Preparing False Evidence

Penal Code 118.1 PC – Police Officer$ Filing False Report$

Spencer v. Peters– Police Fabrication of Evidence – 14th Amendment

Penal Code 148.5 PC – Making a False Police Report in California

Penal Code 115 PC – Filing a False Document in California

Misconduct by Government Know Your Rights Click Here

Under 42 U.S.C. $ection 1983 – Recoverable Damage$

42 U.S. Code § 1983 – Civil Action for Deprivation of Right$

18 U.S. Code § 242 – Deprivation of Right$ Under Color of Law

18 U.S. Code § 241 – Conspiracy against Right$

Section 1983 Lawsuit – How to Bring a Civil Rights Claim

Suing for Misconduct – Know More of Your Right$

Police Misconduct in California – How to Bring a Lawsuit

How to File a complaint of Police Misconduct? (Tort Claim Forms here as well)

Deprivation of Rights – Under Color of the Law

What is Sua Sponte and How is it Used in a California Court?

Removing Corrupt Judges, Prosecutors, Jurors

and other Individuals & Fake Evidence from Your Case

Anti-SLAPP Law in California

Freedom of Assembly – Peaceful Assembly – 1st Amendment Right

How to Recover “Punitive Damages” in a California Personal Injury Case

Pro Se Forms and Forms Information(Tort Claim Forms here as well)

What is Tort?

Tort Claims Form

File Government Claim for Eligible Compensation

Complete and submit the Government Claim Form, including the required $25 filing fee or Fee Waiver Request, and supporting documents, to the GCP.

See Information Guides and Resources below for more information.

Tort Claims – Claim for Damage, Injury, or Death (see below)

Federal – Federal SF-95 Tort Claim Form Tort Claim online here or download it here or here from us

California – California Tort Claims Act – California Tort Claim Form Here or here from us

Complaint for Violation of Civil Rights (Non-Prisoner Complaint) and also UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT PDF

Taken from the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA Forms source

WRITS and WRIT Types in the United States

Appealing/Contesting Case/Order/Judgment/Charge/ Suppressing Evidence

First Things First: What Can Be Appealed and What it Takes to Get Started – Click Here

Options to Appealing– Fighting A Judgment Without Filing An Appeal Settlement Or Mediation

Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 1008 Motion to Reconsider

Penal Code 1385 – Dismissal of the Action for Want of Prosecution or Otherwise

Penal Code 1538.5 – Motion To Suppress Evidence in a California Criminal Case

CACI No. 1501 – Wrongful Use of Civil Proceedings

Penal Code “995 Motions” in California – Motion to Dismiss

WIC § 700.1 – If Court Grants Motion to Suppress as Evidence

Suppression Of Exculpatory Evidence / Presentation Of False Or Misleading Evidence – Click Here

Notice of Appeal — Felony (Defendant) (CR-120) 1237, 1237.5, 1538.5(m) – Click Here

California Motions in Limine – What is a Motion in Limine?

Petition for a Writ of Mandate or Writ of Mandamus (learn more…)

Retrieving Evidence / Internal Investigation Case

Conviction Integrity Unit (“CIU”) of the Orange County District Attorney OCDA – Click Here

Fighting Discovery Abuse in Litigation – Forensic & Investigative Accounting – Click Here

Orange County Data, BodyCam, Police Report, Incident Reports,

and all other available known requests for data below:

APPLICATION TO EXAMINE LOCAL ARREST RECORD UNDER CPC 13321 Click Here

Learn About Policy 814: Discovery Requests OCDA Office – Click Here

Request for Proof In-Custody Form Click Here

Request for Clearance Letter Form Click Here

Application to Obtain Copy of State Summary of Criminal HistoryForm Click Here

Request Authorization Form Release of Case Information – Click Here

Texts / Emails AS EVIDENCE: Authenticating Texts for California Courts

Can I Use Text Messages in My California Divorce?

Two-Steps And Voila: How To Authenticate Text Messages

How Your Texts Can Be Used As Evidence?

California Supreme Court Rules:

Text Messages Sent on Private Government Employees Lines

Subject to Open Records Requests

case law: City of San Jose v. Superior Court – Releasing Private Text/Phone Records of Government Employees

Public Records Practices After the San Jose Decision

The Decision Briefing Merits After the San Jose Decision

CPRA Public Records Act Data Request – Click Here

Here is the Public Records Service Act Portal for all of CALIFORNIA Click Here

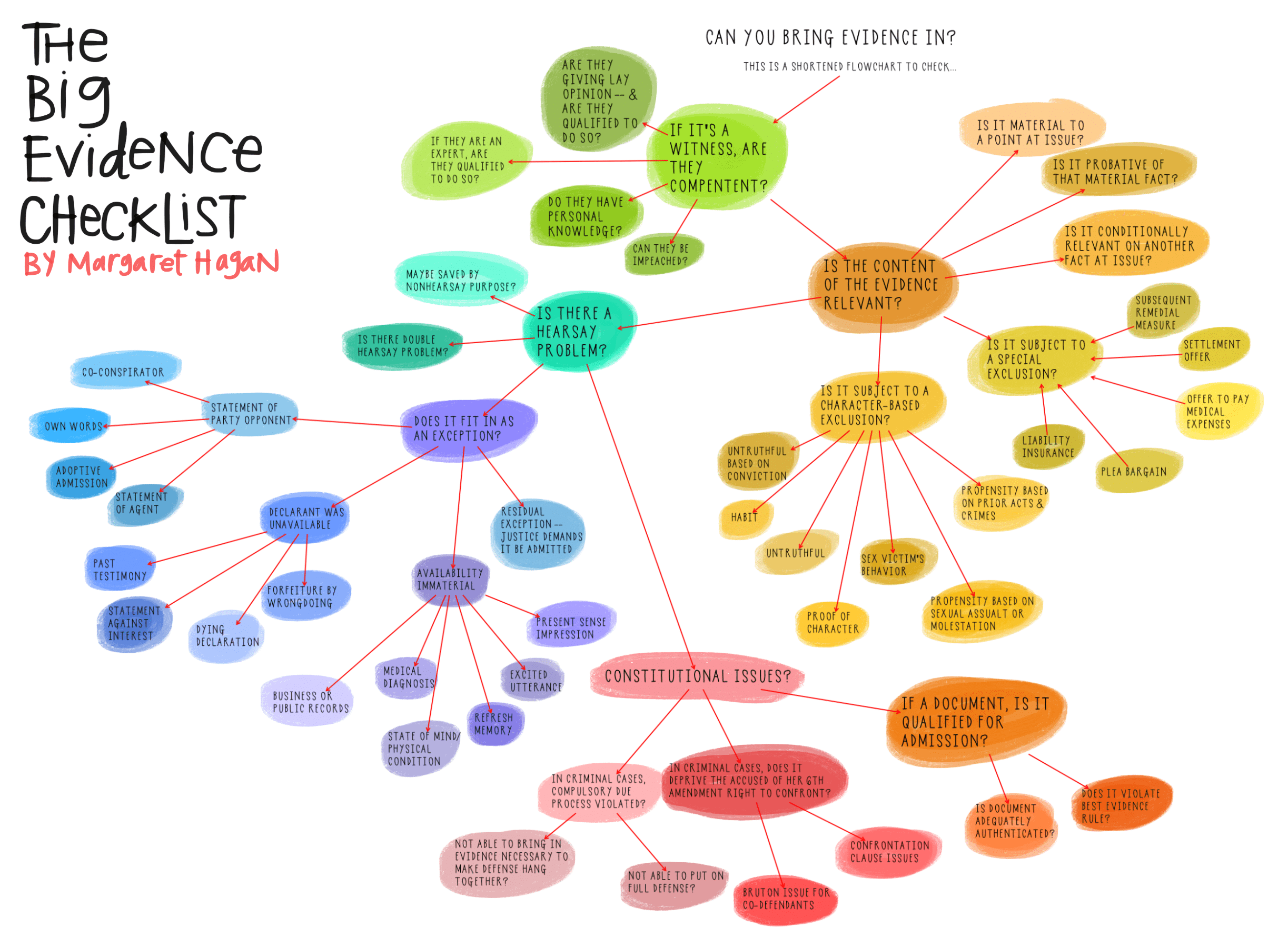

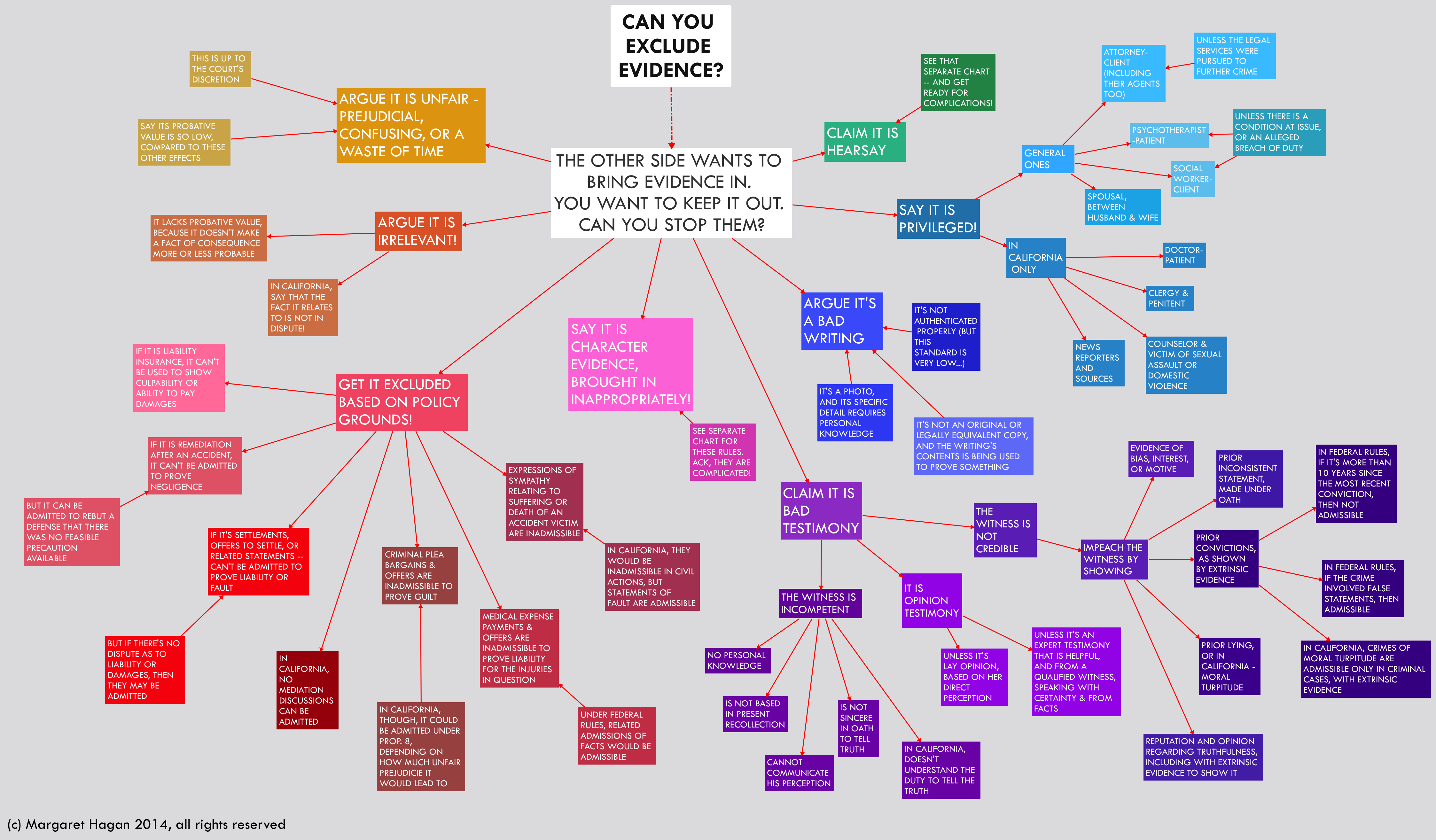

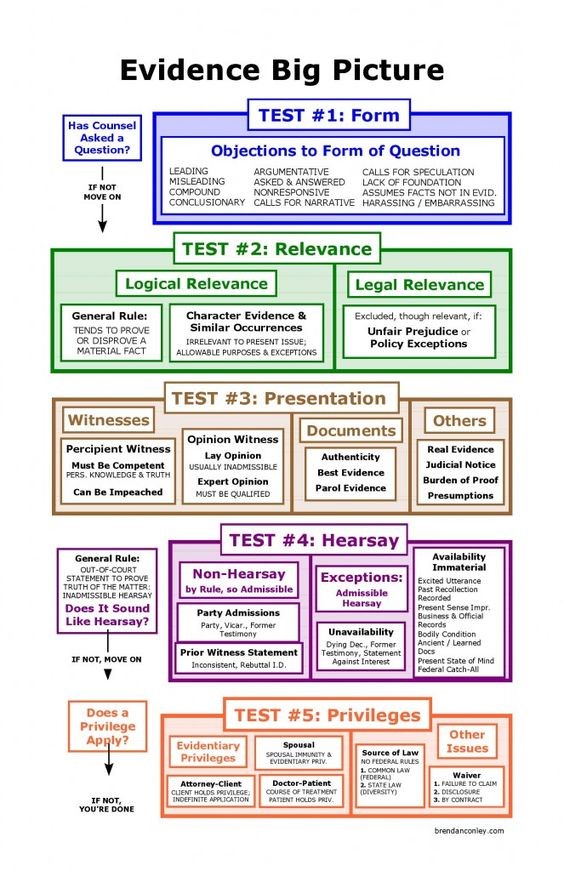

Rules of Admissibility – Evidence Admissibility

Confrontation Clause – Sixth Amendment

Exceptions To The Hearsay Rule – Confronting Evidence

Prosecutor’s Obligation to Disclose Exculpatory Evidence

Successful Brady/Napue Cases – Suppression of Evidence

Cases Remanded or Hearing Granted Based on Brady/Napue Claims

Unsuccessful But Instructive Brady/Napue Cases

ABA – Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

Frivolous, Meritless or Malicious Prosecution – fiduciary duty

Police BodyCam Footage Release

Electronic Audio Recording Request of OC Court Hearings

Cleaning Up Your Record

Tossing Out an Inferior Judgement – When the Judge Steps on Due Process – California Constitution Article VI – Judicial Section 13

Penal Code 851.8 PC – Certificate of Factual Innocence in California

Petition to Seal and Destroy Adult Arrest Records – Download the PC 851.8 BCIA 8270 Form Here

SB 393: The Consumer Arrest Record Equity Act – 851.87 – 851.92 & 1000.4 – 11105 – CARE ACT

Expungement California – How to Clear Criminal Records Under Penal Code 1203.4 PC

How to Vacate a Criminal Conviction in California – Penal Code 1473.7 PC

Seal & Destroy a Criminal Record

Cleaning Up Your Criminal Record in California (focus OC County)

Governor Pardons –What Does A Governor’s Pardon Do

How to Get a Sentence Commuted (Executive Clemency) in California

How to Reduce a Felony to a Misdemeanor – Penal Code 17b PC Motion

PARENT CASE LAW

RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR CHILDREN &

YOUR CONSTITUIONAL RIGHT$ + RULING$

YOU CANNOT GET BACK TIME BUT YOU CAN HIT THOSE IMMORAL NON CIVIC MINDED PUNKS WHERE THEY WILL FEEL YOU = THEIR BANK

Family Law Appeal – Learn about appealing a Family Court Decision Here

9.3 Section 1983 Claim Against Defendant as (Individuals) — 14th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

Amdt5.4.5.6.2 – Parental and Children’s Rights“> – 5th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

9.32 – Interference with Parent / Child Relationship – 14th Amendment this CODE PROTECT$ all US CITIZEN$

California Civil Code Section 52.1

Interference with exercise or enjoyment of individual rights

Parent’s Rights & Children’s Bill of Rights

SCOTUS RULINGS FOR YOUR PARENT RIGHTS