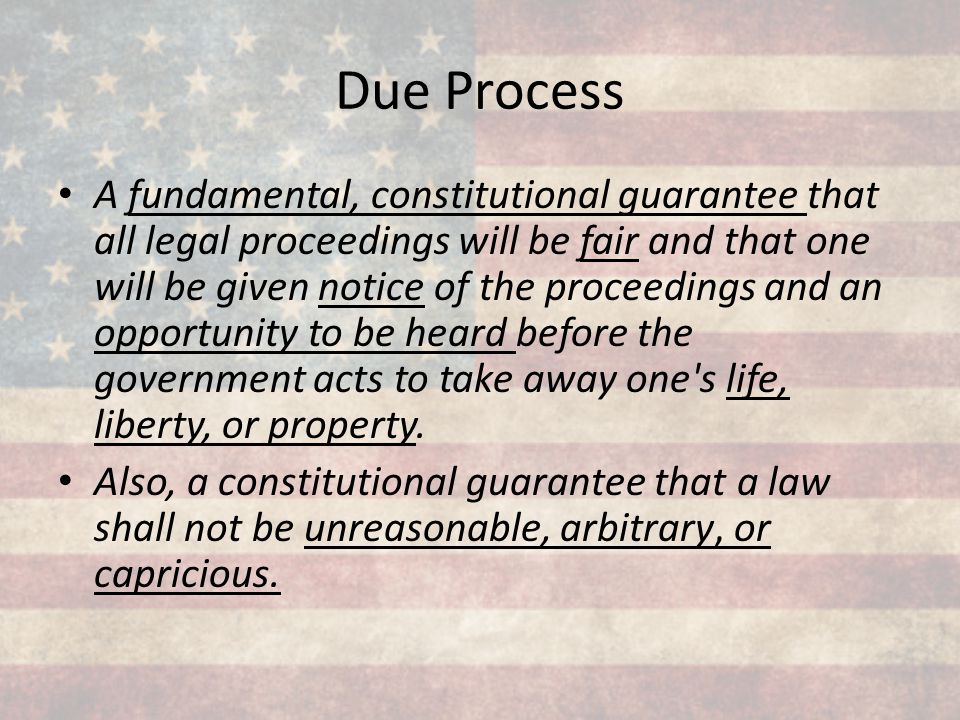

What is a Due Process Violation?

it violates your Constitutional Rights afforded to you in the following amendments

-

Fourth Amendment

-

Fifth Amendment

-

Fourteenth Amendment

-

Prosecutorial misconduct – When prosecutors abuse their power by breaking the law or breaching a professional code of conduct. click here

-

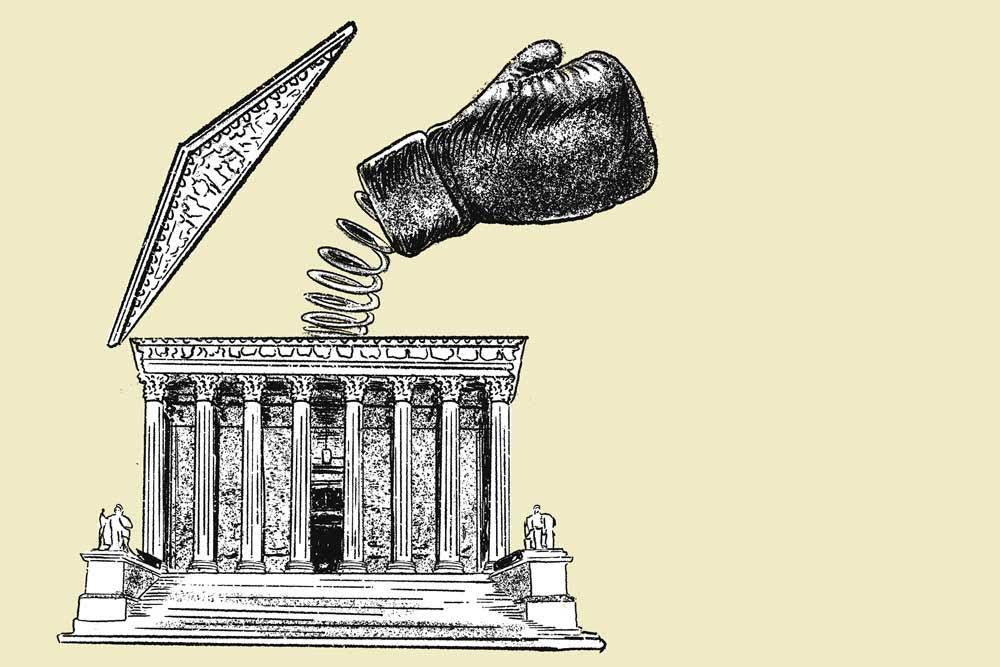

Malicious Prosecution and Thompson Vs. Clark and other SCOTUS Rulings click here

Due Process Introduction

The Constitution states only one command twice. The Fifth Amendment says to the federal government that no one shall be “deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, uses the same eleven words, called the Due Process Clause, to describe a legal obligation of all states. These words have as their central promise an assurance that all levels of American government must operate within the law (“legality”) and provide fair procedures. Most of this essay concerns that promise. We should briefly note, however, three other uses that these words have had in American constitutional law.

Incorporation The Fifth Amendment’s reference to “due process” is only one of many promises of protection the Bill of Rights gives citizens against the federal government. Originally these promises had no application at all against the states (see Barron v City of Baltimore (1833)). However, this attitude faded in Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Company v. City of Chicago (1897), when the court incorporated the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause. In the the middle of the Twentieth Century, a series of Supreme Court decisions found that the Due Process Clause incorporated” most of the important elements of the Bill of Rights and made them applicable to the states. If a Bill of Rights guarantee is “incorporated” in the “due process” requirement of the Fourteenth Amendment, state and federal obligations are exactly the same.

Substantive due process The words “due process” suggest a concern with procedure rather than substance, and that is how many–such as Justice Clarence Thomas, who wrote “the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause is not a secret repository of substantive guarantees against unfairness”–understand the Due Process Clause. However, others believe that the Due Process Clause does include protections of substantive due process–such as Justice Stephen J. Field, who, in a dissenting opinion to the Slaughterhouse Cases wrote that “the Due Process Clause protected individuals from state legislation that infringed upon their “privileges and immunities” under the federal Constitution. Field’s dissenting opinion is often seen as an important step toward the modern doctrine of substantive due process, a theory that the Court has developed to defend rights that are not mentioned in the Constitution.” Substantive due process has been interpreted to include things such as the right to work in an ordinary kind of job, marry, and to raise one’s children as a parent. In Lochner v New York (1905), the Supreme Court found unconstitutional a New York law regulating the working hours of bakers, ruling that the public benefit of the law was not enough to justify the substantive due process right of the bakers to work under their own terms. Substantive due process is still invoked in cases today, but not without criticism (See this Stanford Law Review article to see substantive due process as applied to contemporary issues). The promise of legality and fair procedure Historically, the clause reflects the Magna Carta of Great Britain, King John’s thirteenth century promise to his noblemen that he would act only in accordance with law (“legality”) and that all would receive the ordinary processes (procedures) of law. It also echoes Great Britain’s Seventeenth Century struggles for political and legal regularity, and the American colonies’ strong insistence during the pre-Revolutionary period on observance of regular legal order. The requirement that government function in accordance with law is, in itself, ample basis for understanding the stress given these words. A commitment to legality is at the heart of all advanced legal systems, and the Due Process Clause often thought to embody that commitment.

The clause also promises that before depriving a citizen of life, liberty or property, government must follow fair procedures. Thus, it is not always enough for the government just to act in accordance with whatever law there may happen to be. Citizens may also be entitled to have the government observe or offer fair procedures, whether or not those procedures have been provided for in the law on the basis of which it is acting. Action denying the process that is “due” would be unconstitutional. Suppose, for example, state law gives students a right to a public education, but doesn’t say anything about discipline.

Before the state could take that right away from a student, by expelling her for misbehavior, it would have to provide fair procedures, i.e. “due process.” How can we know whether process is due what counts as a “deprivation” of “life, liberty or property”), when it is due, and what procedures have to be followed (what process is “due” in those cases)? If “due process” refers chiefly to procedural subjects, it says very little about these questions. Courts unwilling to accept legislative judgments have to find answers somewhere else. The Supreme Court’s struggles over how to find these answers echo its interpretational controversies over the years, and reflect the changes in the general nature of the relationship between citizens and government.

In the Nineteenth Century government was relatively simple, and its actions relatively limited. Most of the time it sought to deprive its citizens of life, liberty or property it did so through criminal law, for which the Bill of Rights explicitly stated quite a few procedures that had to be followed (like the right to a jury trial) — rights that were well understood by lawyers and courts operating in the long traditions of English common law. Occasionally it might act in other ways, for example in assessing taxes. In Bi-Metallic Investment Co. v. State Board of Equalization (1915), the Supreme Court held that only politics (the citizen’s “power, immediate or remote, over those who make the rule”) controlled the state’s action setting the level of taxes; but if the dispute was about a taxpayer’s individual liability, not a general question, the taxpayer had a right to some kind of a hearing (“the right to support his allegations by arguments however brief and, if need be, by proof however informal”). This left the state a lot of room to say what procedures it would provide, but did not permit it to deny them altogether.

Distinguishing Due Process

Bi-Metallic established one important distinction: the Constitution does not require “due process” for establishing laws; the provision applies when the state acts against individuals “in each case upon individual grounds” — when some characteristic unique to the citizen is involved. Of course there may be a lot of citizens affected; the issue is whether assessing the effect depends “in each case upon individual grounds.” Thus, the due process clause doesn’t govern how a state sets the rules for student discipline in its high schools; but it does govern how that state applies those rules to individual students who are thought to have violated them — even if in some cases (say, cheating on a state-wide examination) a large number of students were allegedly involved.

Even when an individual is unmistakably acted against on individual grounds, there can be a question whether the state has “deprive[d]” her of “life, liberty or property.” The first thing to notice here is that there must be state action. Accordingly, the Due Process Clause would not apply to a private school taking discipline against one of its students (although that school will probably want to follow similar principles for other reasons).

Whether state action against an individual was a deprivation of life, liberty or property was initially resolved by a distinction between “rights” and “privileges.” Process was due if rights were involved, but the state could act as it pleased in relation to privileges. But as modern society developed, it became harder to tell the two apart (ex: whether driver’s licenses, government jobs, and welfare enrollment are “rights” or a “privilege.” An initial reaction to the increasing dependence of citizens on their government was to look at the seriousness of the impact of government action on an individual, without asking about the nature of the relationship affected.

Process was due before the government could take an action that affected a citizen in a grave way.

In the early 1970s, however, many scholars accepted that “life, liberty or property” was directly affected by state action, and wanted these concepts to be broadly interpreted. Two Supreme Court cases involved teachers at state colleges whose contracts of employment had not been renewed as they expected, because of some political positions they had taken. Were they entitled to a hearing before they could be treated in this way? Previously, astate job was a “privilege” and the answer to this question was an emphatic “No!” Now, the Court decided that whether either of the two teachers had “property” would depend in each instance on whether persons in their position, under state law, held some form of tenure. One teacher had just been on a short term contract; because he served “at will” — without any state law claim or expectation to continuation — he had no “entitlement” once his contract expired. The other teacher worked under a longer-term arrangement that school officials seemed to have encouraged him to regard as a continuing one. This could create an “entitlement,” the Court said; the expectation need not be based on a statute, and an established custom of treating instructors who had taught for X years as having tenure could be shown. While, thus, some law-based relationship or expectation of continuation had to be shown before a federal court would say that process was “due,” constitutional “property” was no longer just what the common aw called “property”; it now included any legal relationship with the state that state law regarded as in some sense an “entitlement” of the citizen.

Licenses, government jobs protected by civil service, or places on the welfare rolls were all defined by state laws as relations the citizen was entitled to keep until there was some reason to take them away, and therefore process was due before they could be taken away. This restated the formal “right/privilege” idea, but did so in a way that recognized the new dependency of citizens on relations with government, the “new property” as one scholar influentially called it.

When process is due

In its early decisions, the Supreme Court seemed to indicate that when only property rights were at stake (and particularly if there was some demonstrable urgency for public action) necessary hearings could be postponed to follow provisional, even irreversible, government action. This presumption changed in 1970 with the decision in Goldberg v. Kelly, a case arising out of a state-administered welfare program. The Court found that before a state terminates a welfare recipient’s benefits, the state must provide a full hearing before a hearing officer, finding that the Due Process Clause required such a hearing.

What procedures are due

Just as cases have interpreted when to apply due process, others have determined the sorts of procedures which are constitutionally due. This is a question that has to be answered for criminal trials (where the Bill of Rights provides many explicit answers), for civil trials (where the long history of English practice provides some landmarks), and for administrative proceedings, which did not appear on the legal landscape until a century or so after the Due Process Clause was first adopted. Because there are the fewest landmarks, the administrative cases present the hardest issues, and these are the ones we will discuss.

The Goldberg Court answered this question by holding that the state must provide a hearing before an impartial judicial officer, the right to an attorney’s help, the right to present evidence and argument orally, the chance to examine all materials that would be relied on or to confront and cross-examine adverse witnesses, or a decision limited to the record thus made and explained in an opinion. The Court’s basis for this elaborate holding seems to have some roots in the incorporation doctrine.

Many argued that the Goldberg standards were too broad, and in subsequent years, the Supreme Court adopted a more discriminating approach. Process was “due” to the student suspended for ten days, as to the doctor deprived of his license to practice medicine or the person accused of being a security risk; yet the difference in seriousness of the outcomes, of the charges, and of the institutions involved made it clear there could be no list of procedures that were always “due.” What the Constitution required would inevitably be dependent on the situation. What process is “due” is a question to which there cannot be a single answer.

A successor case to Goldberg, Mathews v. Eldridge, tried instead to define a method by which due process questions could be successfully presented by lawyers and answered by courts. The approach it defined has remained the Court’s preferred method for resolving questions over what process is due. Mathews attempted to define how judges should ask about constitutionally required procedures. The Court said three factors had to be analyzed:

First, the private interest that will be affected by the official action; second, the risk of an erroneous deprivation of such interest through the procedures used, and the probable value, if any, of additional or substitute procedural safeguards; and finally, the Government’s interest, including the function involved and the fiscal and administrative burdens that the additional or substitute procedural requirement would entail.

Using these factors, the Court first found the private interest here less significant than in Goldberg. A person who is arguably disabled but provisionally denied disability benefits, it said, is more likely to be able to find other “potential sources of temporary income” than a person who is arguably impoverished but provisionally denied welfare assistance.

Respecting the second, it found the risk of error in using written procedures for the initial judgment to be low, and unlikely to be significantly reduced by adding oral or confrontational procedures of the Goldberg variety. It reasoned that disputes over eligibility for disability insurance typically concern one’s medical condition, which could be decided, at least provisionally, on the basis of documentary submissions; it was impressed that Eldridge had full access to the agency’s files, and the opportunity to submit in writing any further material he wished. Finally, the Court now attached more importance than the Goldberg Court had to the government’s claims for efficiency. In particular, the Court assumed (as the Goldberg Court had not) that “resources available for any particular program of social welfare are not unlimited.” Thus additional administrative costs for suspension hearings and payments while those hearings were awaiting resolution to persons ultimately found undeserving of benefits would subtract from the amounts available to pay benefits for those undoubtedly eligible to participate in the program. The Court also gave some weight to the “good-faith judgments” of the plan administrators what appropriate consideration of the claims of applicants would entail.

Matthews thus reorients the inquiry in a number of important respects. First, it emphasizes the variability of procedural requirements. Rather than create a standard list of procedures that constitute the procedure that is “due,” the opinion emphasizes that each setting or program invites its own assessment. About the only general statement that can be made is that persons holding interests protected by the due process clause are entitled to “some kind of hearing.” Just what the elements of that hearing might be, however, depends on the concrete circumstances of the particular program at issue. Second, that assessment is to be made concretely and holistically. It is not a matter of approving this or that particular element of a procedural matrix in isolation, but of assessing the suitability of the ensemble in context. Third, and particularly important in its implications for litigation seeking procedural change, the assessment is to be made at the level of program operation, rather than in terms of the particular needs of the particular litigants involved in the matter before the Court. Cases that are pressed to appellate courts often are characterized by individual facts that make an unusually strong appeal for proceduralization.

Indeed, one can often say that they are chosen for that appeal by the lawyers, when the lawsuit is supported by one of the many American organizations that seeks to use the courts to help establish their view of sound social policy.

Finally, and to similar effect, the second of the stated tests places on the party challenging the existing procedures the burden not only of demonstrating their insufficiency, but also of showing that some specific substitute or additional procedure will work a concrete improvement justifying its additional cost.

Thus, it is inadequate merely to criticize. The litigant claiming procedural insufficiency must be prepared with a substitute program that can itself be justified.

The Mathews approach is most successful when it is viewed as a set of instructions to attorneys involved in litigation concerning procedural issues. Attorneys now know how to make a persuasive showing on a procedural “due process” claim, and the probable effect of the approach is to discourage litigation drawing its motive force from the narrow (even if compelling) circumstances of a particular individual’s position.

The hard problem for the courts in the Mathews approach, which may be unavoidable, is suggested by the absence of fixed doctrine about the content of “due process” and by the very breadth of the inquiry required to establish its demands in a particular context. A judge has few reference points to begin with, and must decide on the basis of considerations (such as the nature of a government program or the probable impact of a procedural requirement) that are very hard to develop in a trial.

While there is no definitive list of the “required procedures” that due process requires, Judge Henry Friendly generated a list that remains highly influential, as to both content and relative priority:

- An unbiased tribunal.

- Notice of the proposed action and the grounds asserted for it.

- Opportunity to present reasons why the proposed action should not be taken.

- The right to present evidence, including the right to call witnesses.

- The right to know opposing evidence.

- The right to cross-examine adverse witnesses.

- A decision based exclusively on the evidence presented.

- Opportunity to be represented by counsel.

- Requirement that the tribunal prepare a record of the evidence presented.

- Requirement that the tribunal prepare written findings of fact and reasons for its decision.

This is not a list of procedures which are required to prove due process, but rather a list of the kinds of procedures that might be claimed in a “due process” argument, roughly in order of their perceived importance.

What Does the 4th Amendment Mean?

The Constitution, through the Fourth Amendment, protects people from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government. The Fourth Amendment, however, is not a guarantee against all searches and seizures, but only those that are deemed unreasonable under the law.

Searches and seizures inside a home without a warrant are presumptively unreasonable.

Payton v. New York, 445 U.S. 573 (1980).

However, there are some exceptions. A warrantless search may be lawful:

If an officer is given consent to search; Davis v. United States, 328 U.S. 582 (1946)

If the search is incident to a lawful arrest; United States v. Robinson, 414 U.S. 218 (1973)

If there is probable cause to search and exigent circumstances; Payton v. New York, 445 U.S. 573 (1980)

If the items are in plain view; Maryland v. Macon, 472 U.S. 463 (1985).

A Person

When an officer observes unusual conduct which leads him reasonably to conclude that criminal activity may be afoot, the officer may briefly stop the suspicious person and make reasonable inquiries aimed at confirming or dispelling the officer’s suspicions.

Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968)

Minnesota v. Dickerson, 508 U.S. 366 (1993)

Schools

School officials need not obtain a warrant before searching a student who is under their authority; rather, a search of a student need only be reasonable under all the circumstances.

New Jersey v. TLO, 469 U.S. 325 (1985)

Cars

Where there is probable cause to believe that a vehicle contains evidence of a criminal activity, an officer may lawfully search any area of the vehicle in which the evidence might be found.

Arizona v. Gant, 129 S. Ct. 1710 (2009),

An officer may conduct a traffic stop if he has reasonable suspicion that a traffic violation has occurred or that criminal activity is afoot.

Berekmer v. McCarty, 468 U.S. 420 (1984),

United States v. Arvizu, 534 U.S. 266 (2002).

An officer may conduct a pat-down of the driver and passengers during a lawful traffic stop; the police need not believe that any occupant of the vehicle is involved in a criminal activity.

Arizona v. Johnson, 555 U.S. 323 (2009).

The use of a narcotics detection dog to walk around the exterior of a car subject to a valid traffic stop does not require reasonable, explainable suspicion.

Illinois v. Cabales, 543 U.S. 405 (2005).

Special law enforcement concerns will sometimes justify highway stops without any individualized suspicion.

Illinois v. Lidster, 540 U.S. 419 (2004).

An officer at an international border may conduct routine stops and searches.

United States v. Montoya de Hernandez, 473 U.S. 531 (1985).

A state may use highway sobriety checkpoints for the purpose of combating drunk driving.

Michigan Dept. of State Police v. Sitz, 496 U.S. 444 (1990).

A state may set up highway checkpoints where the stops are brief and seek voluntary cooperation in the investigation of a recent crime that has occurred on that highway.

Illinois v. Lidster, 540 U.S. 419 (2004).

However, a state may not use a highway checkpoint program whose primary purpose is the discovery and interdiction of illegal narcotics.

City of Indianapolis v. Edmond, 531 U.S. 32 (2000).

In an earlier post we introduced the subject of how the concept of due process interacts with the criminal justice system. Although not all of the amendments that comprise the Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution are related to procedural due process, the 4th, 5th, 6th and 8th Amendments are directly connected to it. We will briefly cover each of these amendments going forward, starting with the 4th Amendment.

The 4th Amendment safeguards against unreasonable searches and seizures of persons and property, and except for situations that courts have carved out as exceptions (see below) requires the use of search and arrest warrants based on probable cause. Evidence gathered by the police in violation of the 4th Amendment cannot be used against you; courts have referred to this exclusion as the “fruit of the poisonous tree” rule.

Characteristics of the 4th Amendment include:

- As with due process rights overall, it protects against government action and not actions of private individuals.

- It is not a prohibition on all searches and seizures. To qualify for its protection, you must have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the place or the item that the police seek to seize.

- What constitutes a “search or seizure” depends on the immediate circumstances. For example, if a police officer stops you on the street and starts asking you questions, that is not a search or a seizure (and conversely you are not obligated to answer any of those questions). But if the officer seeks to search your clothing or personal effects without a warrant, then he must have at least a reasonable suspicion in advance that you have been engaged in some criminal activity.

- If a police officer has probable cause to believe that you have committed a crime, then he can arrest you without having to obtain an arrest warrant first. Or, if you have committed a misdemeanor crime in the officer’s presence no arrest warrant is needed. But unless the officer is in “hot pursuit” of someone who has committed a felony and is trying to flee, any arrest in a private place will ordinarily require the issuance of an arrest warrant.

Torres v. Madrid (2021)

Author: John Roberts

The application of physical force to the body of a person with intent to restrain is a seizure even if the person does not submit and is not subdued.

Kansas v. Glover (2020)

Author: Clarence Thomas

When an officer lacks information negating an inference that a vehicle is driven by its owner, an investigative traffic stop made after running a vehicle’s license plate and learning that the registered owner’s driver’s license has been revoked is reasonable.

Collins v. Virginia (2018)

Author: Sonia Sotomayor

The automobile exception does not permit the warrantless entry of a home or its curtilage to search a vehicle therein.

Carpenter v. U.S. (2018)

Author: John Roberts

The government’s acquisition of an individual’s cell-site records was a Fourth Amendment search.

Utah v. Strieff (2016)

Author: Clarence Thomas

The discovery of a valid, pre-existing, and untainted arrest warrant attenuated the connection between the unconstitutional investigatory stop and the evidence seized incident to a lawful arrest.

Rodriguez v. U.S. (2015)

Author: Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Without reasonable suspicion, police extension of a traffic stop to conduct a dog sniff violates the Constitution’s shield against unreasonable seizures.

Fernandez v. California (2014)

Author: Samuel A. Alito, Jr.

The holding in Randolph is limited to situations in which the objecting occupant is physically present.

Heien v. North Carolina (2014)

Author: John Roberts

When an officer’s mistake of law was reasonable, there was a reasonable suspicion justifying a stop under the Fourth Amendment.

Riley v. California (2014)

Author: John Roberts

Without a warrant, the police generally may not search digital information on a cell phone seized from an individual who has been arrested.

Florida v. Jardines (2013)

Author: Antonin Scalia

Using a drug-sniffing dog on a homeowner’s porch to investigate the contents of the home is a search within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

Maryland v. King (2013)

Author: Anthony Kennedy

When officers make an arrest supported by probable cause to hold for a serious offense and bring the suspect to the station to be detained in custody, taking and analyzing a cheek swab of the arrestee’s DNA is, like fingerprinting and photographing, a legitimate police booking procedure that is reasonable under the Fourth Amendment.

U.S. v. Jones (2012)

Author: Antonin Scalia

The government’s attachment of a GPS device to a vehicle, and its use of that device to monitor the vehicle’s movements, constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment.

Davis v. U.S. (2011)

Author: Samuel A. Alito, Jr.

Searches conducted in objectively reasonable reliance on binding appellate precedent are not subject to the exclusionary rule.

Kentucky v. King (2011)

Author: Samuel A. Alito, Jr.

The exigent circumstances rule applies when the police do not create the exigency by engaging or threatening to engage in conduct that violates the Fourth Amendment.

Arizona v. Johnson (2009)

Author: Ruth Bader Ginsburg

In a traffic stop setting, the first Terry condition (a lawful investigatory stop) is met whenever it is lawful for police to detain an automobile and its occupants pending inquiry into a vehicular violation. The police need not have cause to believe that any occupant of the vehicle is involved in criminal activity. To justify a patdown of the driver or a passenger during a traffic stop, however, the police must harbor reasonable suspicion that the person subjected to the frisk is armed and dangerous.

Arizona v. Gant (2009)

Author: John Paul Stevens

Police may search the passenger compartment of a vehicle incident to a recent occupant’s arrest only if it is reasonable to believe that the arrestee might access the vehicle at the time of the search or that the vehicle contains evidence of the offense of arrest.

Safford Unified School District #1 v. Redding (2009)

Author: David Souter

The required knowledge component of reasonable suspicion for a school administrator’s evidence search is that it raise a moderate chance of finding evidence of wrongdoing.

Herring v. U.S. (2009)

Author: John Roberts

When police mistakes leading to an unlawful search are the result of isolated negligence attenuated from the search, rather than systemic error or reckless disregard of constitutional requirements, the exclusionary rule does not apply.

Brendlin v. California (2007)

Author: David Souter

When police make a traffic stop, a passenger in the car (not only the driver) is seized for Fourth Amendment purposes and thus may challenge the stop’s constitutionality.

Scott v. Harris (2007)

Author: Antonin Scalia

When opposing parties tell two different stories, one of which is blatantly contradicted by the record so that no reasonable jury could believe it, a court should not adopt that version of the facts for the purposes of ruling on a motion for summary judgment. Also, a police officer’s attempt to terminate a dangerous high-speed car chase that threatens the lives of innocent bystanders does not violate the Fourth Amendment, even when it places the fleeing motorist at risk of serious injury or death.

Georgia v. Randolph (2006)

Author: David Souter

A physically present co-occupant’s stated refusal to permit entry to a residence rendered a warrantless entry and search unreasonable and invalid as to them.

Brigham City v. Stuart (2006)

Author: John Roberts

Police may enter a home without a warrant when they have an objectively reasonable basis for believing that an occupant is seriously injured or imminently threatened with such injury.

Illinois v. Caballes (2005)

Author: John Paul Stevens

A dog sniff conducted during a lawful traffic stop that reveals no information other than the location of a substance that no individual has a right to possess does not violate the Fourth Amendment.

Illinois v. Lidster (2004)

Author: Stephen Breyer

A highway checkpoint where police stopped motorists to ask for information about a recent accident was reasonable under the Fourth Amendment.

Groh v. Ramirez (2004)

Author: John Paul Stevens

When a warrant did not describe the items to be seized, the fact that the application for the warrant adequately described the items did not save the warrant.

Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial District Court of Nevada (2004)

Author: Anthony Kennedy

Terry principles permit a state to require a suspect to disclose their name in the course of a Terry stop.

Thornton v. U.S. (2004)

Author: William Rehnquist

Belton governs even when an officer does not make contact until the person arrested has left the vehicle.

U.S. v. Banks (2003)

Author: David Souter

A 15-to-20-second wait before forcible entry satisfied the Fourth Amendment.

Maryland v. Pringle (2003)

Author: William Rehnquist

To determine whether an officer had probable cause to make an arrest, a court must examine the events leading up to the arrest, and then decide whether these historical facts, viewed from the standpoint of an objectively reasonable police officer, amount to probable cause.

U.S. v. Drayton (2002)

Author: Anthony Kennedy

The Fourth Amendment does not require police officers to advise bus passengers of their right not to cooperate and to refuse consent to searches.

Illinois v. McArthur (2001)

Author: Stephen Breyer

Police officers acted reasonably when, with probable cause to believe that a man had hidden marijuana in his home, they prevented that man from entering the home for about two hours while they obtained a search warrant.

Ferguson v. Charleston (2001)

Author: John Paul Stevens

A state hospital’s performance of a diagnostic test to obtain evidence of a patient’s criminal conduct for law enforcement purposes is an unreasonable search if the patient has not consented to the procedure.

Atwater v. Lago Vista (2001)

Author: David Souter

The Fourth Amendment does not forbid a warrantless arrest for a minor criminal offense, such as a misdemeanor seatbelt violation punishable only by a fine.

Kyllo v. U.S. (2001)

Author: Antonin Scalia

When the government uses a device that is not in general public use to explore details of a private home that would previously have been unknowable without physical intrusion, the surveillance is a Fourth Amendment search, and it is presumptively unreasonable without a warrant.

Indianapolis v. Edmond (2000)

Author: Sandra Day O’Connor

A vehicle checkpoint violates the Fourth Amendment when its primary purpose is indistinguishable from the general interest in crime control.

Florida v. J.L. (2000)

Author: Ruth Bader Ginsburg

An anonymous tip that a person is carrying a gun is not, without more, sufficient to justify a police officer’s stop and frisk of that person.

Bond v. U.S. (2000)

Author: William Rehnquist

A border patrol agent’s physical manipulation of a bus passenger’s carry-on bag violated the Fourth Amendment proscription against unreasonable searches.

Illinois v. Wardlow (2000)

Author: William Rehnquist

An individual’s presence in a “high crime area”, standing alone, is not enough to support a reasonable, particularized suspicion of criminal activity. However, a location’s characteristics are relevant in determining whether the circumstances are sufficiently suspicious to warrant further investigation.

Wyoming v. Houghton (1999)

Author: Antonin Scalia

Police officers with probable cause to search a car may inspect passengers’ belongings found in the car that are capable of concealing the object of the search.

Knowles v. Iowa (1998)

Author: William Rehnquist

While the authority to conduct a full field search as incident to an arrest was established as a bright line rule under Robinson, that rule should not be extended to a situation in which the concern for officer safety is not present to the same extent, and the concern for destruction or loss of evidence is not present at all.

Richards v. Wisconsin (1997)

Author: John Paul Stevens

A no-knock entry is justified when the police have a reasonable suspicion that knocking and announcing their presence would be dangerous or futile under the circumstances, or that it would inhibit the effective investigation of the crime.

Maryland v. Wilson (1997)

Author: William Rehnquist

An officer making a traffic stop may order passengers to get out of the car pending completion of the stop.

Whren v. U.S. (1996)

Author: Antonin Scalia

The temporary detention of a motorist on probable cause to believe that they have violated the traffic laws does not violate the Fourth Amendment prohibition against unreasonable seizures, even if a reasonable officer would not have stopped the motorist without an additional law enforcement objective.

Ohio v. Robinette (1996)

Author: William Rehnquist

The Fourth Amendment does not require that a lawfully seized defendant be advised that they are free to go before their consent to search will be recognized as voluntary.

Arizona v. Evans (1995)

Author: William Rehnquist

The exclusionary rule does not require the suppression of evidence seized in violation of the Fourth Amendment when the erroneous information resulted from clerical errors of court employees.

Wilson v. Arkansas (1995)

Author: Clarence Thomas

The common-law knock and announce principle forms a part of the Fourth Amendment reasonableness inquiry.

Minnesota v. Dickerson (1993)

Author: Byron White

The police may seize non-threatening contraband detected through the sense of touch during a protective patdown search of the sort permitted by Terry, so long as the search stays within the bounds marked by Terry.

Florida v. Bostick (1991)

Author: Sandra Day O’Connor

There is no per se rule that every encounter on a bus is a seizure. The appropriate test is whether, taking into account all the circumstances surrounding the encounter, a reasonable passenger would feel free to decline the officers’ requests or otherwise terminate the encounter.

California v. Acevedo (1991)

Author: Harry Blackmun

In a search extending only to a container within a vehicle, the police may search the container without a warrant when they have probable cause to believe that it holds contraband or evidence.

California v. Hodari D. (1991)

Author: Antonin Scalia

To constitute a seizure of the person, just as to constitute an arrest, there must be either the application of physical force, however slight, or submission to an officer’s show of authority to restrain the subject’s liberty.

Florida v. Jimeno (1991)

Author: William Rehnquist

A criminal suspect’s Fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable searches is not violated when they give police permission to search their car, and the police open a closed container in the car that might reasonably hold the object of the search.

New York v. Harris (1990)

Author: Byron White

When the police have probable cause to arrest a suspect, the exclusionary rule does not bar the use of a statement made by the defendant outside their home, even if the statement is taken after an arrest made in the home in violation of Payton.

Alabama v. White (1990)

Author: Byron White

Factors for determining whether an informant’s tip establishes probable cause are also relevant in the Terry reasonable suspicion context, although allowance must be made in applying them for the lesser showing required to meet that standard.

Maryland v. Buie (1990)

Author: Byron White

The Fourth Amendment permits a properly limited protective sweep in conjunction with an in-home arrest when the searching officer has a reasonable belief based on specific and articulable facts that the area to be swept harbors a person posing a danger to those on the arrest scene.

Michigan Dept. of State Police v. Sitz (1990)

Author: William Rehnquist

The use of highway sobriety checkpoints does not violate the Fourth Amendment.

Florida v. Riley (1989)

Author: Byron White

The Fourth Amendment does not require the police traveling in the public airways at an altitude of 400 feet to obtain a warrant to observe what is visible to the naked eye.

California v. Greenwood (1988)

Author: Byron White

The Fourth Amendment does not prohibit the warrantless search and seizure of garbage left for collection outside the curtilage of a home.

Murray v. U.S. (1988)

Author: Antonin Scalia

The Fourth Amendment does not require the suppression of evidence initially discovered during police officers’ illegal entry of private premises if the evidence is also discovered during a later search pursuant to a valid warrant that is wholly independent of the initial illegal entry.

Illinois v. Krull (1987)

Author: Harry Blackmun

The Fourth Amendment exclusionary rule does not apply to evidence obtained by police who acted in objectively reasonable reliance on a statute authorizing warrantless administrative searches, which is subsequently found to violate the Fourth Amendment.

Arizona v. Hicks (1987)

Author: Antonin Scalia

A truly cursory inspection, which involves merely looking at what is already exposed to view without disturbing it, is not a search for Fourth Amendment purposes and therefore does not even require reasonable suspicion.

Colorado v. Bertine (1987)

Author: William Rehnquist

Reasonable police regulations related to inventory procedures, administered in good faith, satisfy the Fourth Amendment.

Dow Chemical Co. v. U.S. (1986)

Author: Warren Burger

The Fourth Amendment did not prohibit the Environmental Protection Agency from taking, without a warrant, aerial photographs of the defendant’s plant complex from an aircraft lawfully in public navigable airspace.

Tennessee v. Garner (1985)

Author: Byron White

A police officer may not seize an unarmed, non-dangerous suspect by shooting them dead. However, when an officer has probable cause to believe that a suspect poses a threat of serious physical harm, either to the officer or to others, it is not constitutionally unreasonable to prevent escape by using deadly force.

New Jersey v. T.L.O. (1985)

Author: Byron White

The Fourth Amendment prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures applies to searches conducted by public school officials, but the more lenient standard of reasonable suspicion applies.

California v. Carney (1985)

Author: Warren Burger

The two justifications for the vehicle exception to the warrant requirement of the Fourth Amendment come into play when a vehicle is being used on the highways or is capable of such use and is found stationary in a place not regularly used for residential purposes. The vehicle is readily mobile, and there is a reduced expectation of privacy stemming from the pervasive regulation of vehicles capable of traveling on highways.

Winston v. Lee (1984)

Author: William Brennan

The reasonableness of surgical intrusions beneath the skin depends on a case-by-case approach, in which the individual’s interests in privacy and security are weighed against society’s interests in conducting the procedure to obtain evidence for fairly determining guilt or innocence.

Massachusetts v. Upton (1984)

Author: Per Curiam

Even when no single piece of evidence in an affidavit was conclusive, the pieces fit neatly together and thus supported the magistrate’s determination of probable cause.

Oliver v. U.S. (1984)

Author: Lewis Powell

The government’s intrusion upon open fields is not one of the unreasonable searches proscribed by the Fourth Amendment. No expectation of privacy legitimately attaches to open fields.

U.S. v. Leon (1984)

Author: Byron White

The Fourth Amendment exclusionary rule should not be applied to bar the use in the prosecution’s case in chief of evidence obtained by officers acting in reasonable reliance on a search warrant issued by a detached and neutral magistrate but ultimately found to be invalid.

Segura v. U.S. (1984)

Author: Warren Burger

Securing a dwelling on the basis of probable cause to prevent the destruction or removal of evidence while a search warrant is being sought is not an unreasonable seizure of the dwelling or its contents.

U.S. v. Place (1983)

Author: Sandra Day O’Connor

The investigative procedure of subjecting luggage to a sniff test by a well-trained narcotics detection dog does not constitute a search within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

Michigan v. Long (1983)

Author: Sandra Day O’Connor

If a state court decision indicates clearly and expressly that it is based on bona fide separate, adequate, and independent state grounds, the Supreme Court will not review the decision. Also, a search of the passenger compartment of an automobile, limited to those areas in which a weapon may be placed or hidden, is permissible if the police officer possesses a reasonable belief based on specific and articulable facts that, taken together with the rational inferences from those facts, reasonably warrant the officer to believe that the suspect is dangerous and that the suspect may gain immediate control of weapons.

Illinois v. Gates (1983)

Author: William Rehnquist

The rigid two-pronged test under Aguilar and Spinelli for determining whether an informant’s tip establishes probable cause for issuance of a warrant is abandoned, and the totality of the circumstances approach that traditionally has informed probable cause determinations is substituted in its place.

Illinois v. Lafayette (1983)

Author: Warren Burger

Consistent with the Fourth Amendment, it is reasonable for police to search the personal effects of a person under lawful arrest as part of the routine administrative procedure at a police station incident to booking and jailing the suspect.

U.S. v. Ross (1982)

Author: John Paul Stevens

Police officers who have legitimately stopped a vehicle and who have probable cause to believe that contraband is concealed somewhere in it may conduct a warrantless search of the vehicle that is as thorough as a magistrate could authorize by warrant.

Steagald v. U.S. (1981)

Author: Thurgood Marshall

An arrest warrant, as opposed to a search warrant, is inadequate to protect the Fourth Amendment interests of persons not named in the warrant when their home is searched without their consent and in the absence of exigent circumstances.

New York v. Belton (1981)

Author: Potter Stewart

When a policeman has made a lawful custodial arrest of the occupant of an automobile, they may search the passenger compartment of that automobile as a contemporaneous incident of that arrest. The police may also examine the contents of any containers found within the passenger compartment.

U.S. v. Cortez (1981)

Author: Warren Burger

In determining what cause is sufficient to authorize police to stop a person, the totality of the circumstances (the whole picture) must be taken into account. Based upon that whole picture, the detaining officers must have a particularized and objective basis for suspecting the particular person stopped of criminal activity.

Payton v. New York (1980)

Author: John Paul Stevens

The Fourth Amendment prohibits the police from making a warrantless and non-consensual entry into the home of a suspect to make a routine felony arrest.

Rawlings v. Kentucky (1980)

Author: William Rehnquist

When the arrest followed quickly after the search of the defendant’s person, it is not important that the search preceded the arrest, rather than vice versa.

Arkansas v. Sanders (1979)

Author: Lewis Powell

In the absence of exigent circumstances, police are required to obtain a warrant before searching luggage taken from an automobile properly stopped and searched for contraband.

U.S. v. Caceres (1979)

Author: John Paul Stevens

The exclusionary rule does not require that all evidence obtained in violation of regulations concerning electronic eavesdropping be excluded.

Franks v. Delaware (1978)

Author: Harry Blackmun

When a defendant makes a substantial preliminary showing that a false statement knowingly and intentionally, or with reckless disregard for the truth, was included by the affiant in the warrant affidavit, and if the allegedly false statement is necessary to the finding of probable cause, the Fourth Amendment requires that a hearing be held at the defendant’s request.

Zurcher v. Stanford Daily (1978)

Author: Byron White

When the state does not seek to seize persons but instead seeks to seize things, there is no apparent basis in the language of the Fourth Amendment for also imposing the requirements for a valid arrest: probable cause to believe that a third party occupying the place to be searched is implicated in the crime. In other words, valid warrants may be issued to search any property, whether or not occupied by a third party, at which there is probable cause to believe that fruits, instrumentalities, or evidence of a crime will be found.

U.S. v. Ceccolini (1978)

Author: William Rehnquist

The exclusionary rule should be invoked with much greater reluctance when the claim is based on a causal relationship between a constitutional violation and the discovery of a live witness than when a similar claim is advanced to support suppression of an inanimate object.

Rakas v. Illinois (1978)

Author: William Rehnquist

A person aggrieved by an illegal search and seizure only through the introduction of damaging evidence secured by a search of a third person’s premises or property has not had any of their Fourth Amendment rights infringed.

Andresen v. Maryland (1976)

Author: Harry Blackmun

Although the Fifth Amendment may protect an individual from complying with a subpoena for the production of their personal records in their possession, a seizure of the same materials by law enforcement officers is different because the individual against whom the search is directed is not required to aid in the discovery, production, or authentication of incriminating evidence.

U.S. v. Watson (1976)

Author: Byron White

The cases construing the Fourth Amendment reflect the common-law rule that a peace officer was permitted to arrest without a warrant for a misdemeanor or felony committed in their presence, as well as for a felony not committed in their presence if there was reasonable ground for making the arrest.

Gerstein v. Pugh (1975)

Author: Lewis Powell

The Fourth Amendment requires a judicial determination of probable cause as a prerequisite to extended restraint of liberty following an arrest.

U.S. v. Edwards (1974)

Author: Byron White

Once an accused has been lawfully arrested and is in custody, the effects in their possession at the place of detention that were subject to search at the time and place of the arrest may lawfully be searched and seized without a warrant even after a substantial time lapse between the arrest and later administrative processing, on the one hand, and the taking of the property for use as evidence, on the other.

Schneckloth v. Bustamonte (1973)

Author: Potter Stewart

When the subject of a search is not in custody, and the state would justify a search on the basis of their consent, the state must demonstrate that the consent was voluntary. Voluntariness is determined from the totality of the surrounding circumstances. While knowledge of a right to refuse consent is a factor to be taken into account, the state need not prove that the person knew that they had a right to withhold consent.

U.S. v. Robinson (1973)

Author: William Rehnquist

In the case of a lawful custodial arrest, a full search of the person is not only an exception to the warrant requirement of the Fourth Amendment but also a reasonable search under the Fourth Amendment.

Vale v. Louisiana (1970)

Author: Potter Stewart

Only in a few specifically established and well delineated situations may a warrantless search of a dwelling withstand constitutional scrutiny. These include when there was consent to the search, the officers were responding to an emergency, the officers were in hot pursuit of a fleeing felon, or the goods ultimately seized were in the process of destruction or were about to be removed from the jurisdiction.

Chimel v. California (1969)

Author: Potter Stewart

An arresting officer may search the arrestee’s person to discover and remove weapons and to seize evidence to prevent its concealment or destruction, and they may search the area within the immediate control of the person arrested, meaning the area from which the person might gain possession of a weapon or destructible evidence.

Spinelli v. U.S. (1969)

Author: John Marshall Harlan II

A tip was inadequate to provide the basis for a finding of probable cause that a crime was being committed when it did not set forth any reason to support the conclusion that the informant was reliable and did not sufficiently state the underlying circumstances from which the informant drew their conclusions or sufficiently detail the defendant’s activities.

Terry v. Ohio (1968)

Author: Earl Warren

When a police officer observes unusual conduct that leads him reasonably to conclude in light of his experience that criminal activity may be afoot and that the persons with whom he is dealing may be armed and presently dangerous, when he identifies himself as a policeman and makes reasonable inquiries in the course of investigating this behavior, and when nothing in the initial stages of the encounter serves to dispel his reasonable fear for his own or others’ safety, the officer is entitled for the protection of himself and others in the area to conduct a carefully limited search of the outer clothing of such persons in an attempt to discover weapons that might be used to assault him.

Warden v. Hayden (1967)

Author: William Brennan

The exigencies of a situation in which officers were in pursuit of a suspected armed felon in the house that he had entered only minutes before they arrived permitted their warrantless entry and search. Moreover, the distinction prohibiting seizure of items of only evidential value and allowing seizure of instrumentalities, fruits, or contraband is not required by the Fourth Amendment.

McCray v. Illinois (1967)

Author: Potter Stewart

A state court does not have a duty to require the disclosure of an informer’s identity at a pretrial hearing held for the purpose of determining only the question of probable cause when there was ample evidence in an open and adversary proceeding that the informer was known to the officers to be reliable and that they made the arrest in good faith upon the information that the informer supplied.

Katz v. U.S. (1967)

Author: Potter Stewart

The government’s activities in electronically listening to and recording the defendant’s words violated the privacy on which he justifiably relied while using a telephone booth and thus constituted a search and seizure within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

Schmerber v. California (1966)

Author: William Brennan

The interests in human dignity and privacy that the Fourth Amendment protects forbid any intrusions beyond the body’s surface on the mere chance that desired evidence might be obtained. There must be a clear indication that such evidence will be found.

Aguilar v. Texas (1964)

Author: Arthur Goldberg

Although an affidavit supporting a search warrant may be based on hearsay information, the magistrate must be informed of some of the underlying circumstances on which the person providing the information relied and some of the underlying circumstances from which the affiant concluded that the undisclosed informant was creditable or their information reliable.

Wong Sun v. U.S. (1963)

Author: William Brennan

Statements made by a suspect in his bedroom at the time of his unlawful arrest were the fruit of the agents’ unlawful action and should have been excluded. The narcotics taken from a third party as a result of statements made by the suspect at the time of his arrest were likewise fruits of the unlawful arrest and should not have been admitted. However, when another suspect had been lawfully arraigned and released on his own recognizance after his unlawful arrest and had returned voluntarily several days later when he made an unsigned statement, the connection between his unlawful arrest and the making of that statement was so attenuated that the unsigned statement was not the fruit of the unlawful arrest and was properly admitted.

Mapp v. Ohio (1961)

Author: Tom C. Clark

All evidence obtained by searches and seizures in violation of the federal Constitution is inadmissible in a criminal trial in a state court.

Draper v. U.S. (1959)

Author: Charles Evans Whittaker

Even if the information received by an agent from an informer was hearsay, the agent was legally entitled to consider it in determining whether he had probable cause under the Fourth Amendment and reasonable grounds to believe that the defendant had committed or was committing a violation of the narcotics laws.

Wolf v. Colorado (1949)

Author: Felix Frankfurter

In a prosecution in a state court for a state crime, the Fourteenth Amendment does not forbid the admission of relevant evidence, even though obtained by an unreasonable search and seizure.

Olmstead v. U.S. (1928)

Author: William Howard Taft

Wiretapping was not a search or seizure within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. (This case was overruled by Katz v. U.S. in 1967.)

Carroll v. U.S. (1925)

Author: William Howard Taft

The Fourth Amendment recognizes a necessary difference between a search for contraband in a store, dwelling, or other structure for the search of which a warrant may readily be obtained, and a search of a ship, wagon, automobile, or other vehicle that may be quickly moved out of the locality or jurisdiction in which the warrant must be sought.

Burdeau v. McDowell (1921)

Author: William Rufus Day

The government may retain for use as evidence in the criminal prosecution of their owner incriminating documents that are turned over to it by private individuals who procured them through a wrongful search without the participation or knowledge of any government official.

Gouled v. U.S. (1921)

Author: John Hessin Clarke

Search warrants may not be used as a means of gaining access to a person’s house or office and papers solely for the purpose of making search to secure evidence to be used against them in a criminal or penal proceeding.

Weeks v. U.S. (1914)

Author: William Rufus Day

The tendency of those executing federal criminal laws to obtain convictions by means of unlawful seizures and enforced confessions in violation of federal rights is not to be sanctioned by the courts that are charged with the support of constitutional rights.

What is the 14th Amendment Due Process Clause?

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The Fifth Amendment

The Fifth Amendment says to the federal government that no one shall be“deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, uses the same eleven words, called the Due Process Clause, to describe a legal obligation of all states.

Amdt5.5.1 Overview of Due Process

Fifth Amendment:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

The Fifth Amendment provides that no person

shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.

1 Generally, due process

guarantees protect individual rights by limiting the exercise of government power.2 The Supreme Court has held that the Fifth Amendment, which applies to federal government action, provides persons with both procedural and substantive due process guarantees. If the federal government seeks to deprive a person of a protected life, liberty, or property interest, the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause requires that the government first provide certain procedural protections.3 Procedural due process often requires the government to provide a person with notice and an opportunity for a hearing before such a deprivation.4 In addition, the Supreme Court has interpreted the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause to include substantive due process guarantees that protect certain fundamental constitutional rights from federal government interference, regardless of the procedures that the government follows when enforcing the law.5 Substantive due process has generally dealt with specific subject areas, such as liberty of contract, marriage, or privacy.

The Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause protects all persons within U.S. territory, including corporations,6 aliens,7 and, presumptively, citizens seeking readmission to the United States.8 However, the states are not entitled to due process protections against the federal government.9 The clause is effective in the District of Columbia10 and in territories that are part of the United States,11 but it does not apply of its own force to unincorporated territories.12 Nor does it reach enemy alien belligerents tried by military tribunals outside the territorial jurisdiction of the United States.13 The Clause restrains Congress in addition to the Executive and Judicial Branches and cannot be so construed as to leave Congress free to make any process ‘due process of law’ by enacting legislation to that effect.

14

Due process cases may arise under both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Both amendments use the same language but have a different history.15 The Supreme Court has construed the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause to impose the same due process limitations on the states as the Fifth Amendment does on the federal government.16 Fourteenth Amendment due process case law is therefore relevant to the interpretation of the Fifth Amendment. Except for areas in which the federal government is the actor, much of the Constitution Annotated‘s discussion of due process appears in the Fourteenth Amendment essays.17

Footnotes

- Jump to essay-1U.S. Const. amend. V.

- Jump to essay-2Due Process, Black’s Law Dictionary 610 (10th ed. 2014).

- Jump to essay-3See Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471, 481 (1972) (citing Cafeteria & Restaurant Workers Union v. McElroy, 367 U.S. 886, 895 (1961)).

- Jump to essay-4Twining v. New Jersey, 211 U.S. 78, 110 (1908); Jacob v. Roberts, 223 U.S. 261, 265 (1912).

- Jump to essay-5E.g., Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374, 386–87 (1978) (citing Loving v. Virginia, 388 U. S. 1 (1967)).

- Jump to essay-6Sinking Fund Cases, 99 U.S. 700, 719 (1879).

- Jump to essay-7Wong Wing v. United States, 163 U.S. 228, 238 (1896).

- Jump to essay-8United States v. Ju Toy, 198 U.S. 253, 263 (1905); cf. Quon Quon Poy v. Johnson, 273 U.S. 352 (1927).

- Jump to essay-9South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 323–24 (1966).

- Jump to essay-10Wight v. Davidson, 181 U.S. 371, 384 (1901).

- Jump to essay-11Lovato v. New Mexico, 242 U.S. 199, 201 (1916).

- Jump to essay-12Public Utility Comm’rs v. Ynchausti & Co., 251 U.S. 401, 406 (1920).

- Jump to essay-13Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U.S. 763 (1950); In re Yamashita, 327 U.S. 1 (1946).

- Jump to essay-14Murray’s Lessee v. Hoboken Land & Improvement Co., 59 U.S. (18 How.) 272, 276 (1856). See also Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw’s opinion in Jones v. Robbins, 74 Mass. (8 Gray) 329 (1857).

- Jump to essay-15French v. Barber Asphalt Paving Co., 181 U.S. 324, 328 (1901).

- Jump to essay-16Cf. Arnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S. 134 (1974); Heiner v. Donnan, 285 U.S. 312, 326 (1932) (

The restraint imposed upon legislation by the due process clauses of the two amendments is the same.

); Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo, 298 U.S. 587, 610 (1936). - Jump to essay-17See Amdt14.S1.3 Due Process Generally.

Amdt14.S1.3 Due Process Generally

The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, uses the same eleven words, called the Due Process Clause, to describe a legal obligation of all states.

Fourteenth Amendment, Section 1:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause provides that no state may deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.

1 The Supreme Court has applied the Clause in two main contexts. First, the Court has construed the Clause to provide protections that are similar to those of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause except that, while the Fifth Amendment applies to federal government actions, the Fourteenth Amendment binds the states.2 The Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause guarantees procedural due process,

meaning that government actors must follow certain procedures before they may deprive a person of a protected life, liberty, or property interest.3 The Court has also construed the Clause to protect substantive due process,

holding that there are certain fundamental rights that the government may not infringe even if it provides procedural protections.4

Second, the Court has construed the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause to render many provisions of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states.5 As originally ratified, the Bill of Rights restricted the actions of the federal government but did not limit the actions of state governments. However, following ratification of the Reconstruction Amendment, the Court has interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause to impose on the states many of the Bill of Rights’ limitations, a doctrine sometimes called incorporation

against the states through the Due Process Clause. Litigants bringing constitutional challenges to state government action often invoke the doctrines of procedural or substantive due process or argue that state action violates the Bill of Rights, as incorporated against the states. The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment has thus formed the basis for many high-profile Supreme Court cases.6

The Fourteenth Amendment prohibits states from depriving any person

of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. The Supreme Court has held that this protection extends to all natural persons (i.e., human beings), regardless of race, color, or citizenship.7 The Court has also considered multiple cases about whether the word person

includes artificial persons,

meaning entities such as corporations. As early as the 1870s, the Court appeared to accept that the Clause protects corporations, at least in some circumstances. In the 1877 Granger Cases, the Court upheld various state laws without questioning whether a corporation could raise due process claims.8 In a roughly contemporaneous case arising under the Fifth Amendment, the Court explicitly declared that the United States equally with the States . . . are prohibited from depriving persons or corporations of property without due process of law.

9 Subsequent decisions of the Court have held that a corporation may not be deprived of its property without due process of law.10 By contrast, in multiple cases involving the liberty interest, the Court has held that the Fourteenth Amendment protects the liberty of natural, not artificial, persons.11 Nevertheless, the Court has at times allowed corporations to raise claims not based on the property interest. For instance, in a 1936 case, a newspaper corporation successfully argued that a state law deprived it of liberty of the press.12

A separate question concerns the ability of government officials to invoke the Due Process Clause to protect the interests of their office. Ordinarily, the mere official interest of a public officer, such as the interest in enforcing a law, does not enable him to challenge the constitutionality of a law under the Fourteenth Amendment.13 Moreover, municipal corporations lack standing to invoke the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment in opposition to the will of their creator,

the state.14 However, the Court has acknowledged that state officers have an interest in resisting an endeavor to prevent the enforcement of statutes in relation to which they have official duties,

even if the officials have not sustained any private damage.

15 State officials may therefore ask federal courts to review decisions of state courts declaring state statutes, which [they] seek to enforce, to be repugnant to

the Fourteenth Amendment.16

Footnotes

- Jump to essay-1U.S. Const. amend. XIV.

- Jump to essay-2For discussion of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, see Amdt5.5.1 Overview of Due Process.

- Jump to essay-3See Amdt14.S1.5.1 Overview of Procedural Due Process to Amdt14.S1.5.8.2 Protective Commitment and Due Process.

- Jump to essay-4See Amdt14.S1.6.1 Overview of Substantive Due Process to Amdt14.S1.6.5.3 Civil Commitment and Substantive Due Process.

- Jump to essay-5See Amdt14.S1.4.1 Overview of Incorporation of the Bill of Rights.

- Jump to essay-6Among numerous other examples, see, e.g., W. Va. State Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943); Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963); Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965); McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010).

- Jump to essay-7Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886); Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U.S. 197, 216 (1923). See Hellenic Lines v. Rhodetis, 398 U.S. 306, 309 (1970).

- Jump to essay-8Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113 (1877).

- Jump to essay-9Sinking Fund Cases, 99 U.S. 700, 718–19 (1879).

- Jump to essay-10Smyth v. Ames, 169 U.S. 466, 522, 526 (1898); Kentucky Co. v. Paramount Exch., 262 U.S. 544, 550 (1923); Liggett Co. v. Baldridge, 278 U.S. 105 (1928).

- Jump to essay-11Nw. Life Ins. Co. v. Riggs, 203 U.S. 243, 255 (1906); W. Turf Ass’n v. Greenberg, 204 U.S. 359, 363 (1907); Pierce v. Soc’y of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510, 535 (1925).

- Jump to essay-12Grosjean v. Am. Press Co., 297 U.S. 233, 244 (1936) (

a corporation is a ‘person’ within the meaning of the equal protection and due process of law clauses

). In First Nat’l Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, 435 U.S. 765 (1978), faced with the validity of state restraints upon expression by corporations, the Court did not determine that corporations have First Amendment liberty rights—and other constitutional rights—but decided instead that expression was protected, irrespective of the speaker, because of the interests of the listeners. See id. at 778 n.14. In Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310 (2010), the Court held that the First Amendment prohibits banning political speech based on the speaker’s corporate identity. While Citizens United involved federal regulation, it overruled a prior case that had upheld a related state regulation, Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Com., 494 U.S. 652 (1990). - Jump to essay-13Pennie v. Reis, 132 U.S. 464 (1889); Taylor & Marshall v. Beckham (No. 1), 178 U.S. 548 (1900); Tyler v. Judges of Ct. of Registration, 179 U.S. 405, 410 (1900); Straus v. Foxworth, 231 U.S. 162 (1913); Columbus & Greenville Ry. v. Miller, 283 U.S. 96 (1931).

- Jump to essay-14City of Pawhuska v. Pawhuska Oil Co., 250 U.S. 394 (1919); City of Trenton v. New Jersey, 262 U.S. 182 (1923); Williams v. Mayor of Baltimore, 289 U.S. 36 (1933). But see Madison Sch. Dist. v. WERC, 429 U.S. 167, 175 n.7 (1976) (reserving question whether municipal corporation as an employer has a First Amendment right assertable against a state).

- Jump to essay-15Coleman v. Miller, 307 U.S. 433, 442, 445 (1939); Boynton v. Hutchinson Gas Co., 291 U.S. 656 (1934); S.C. Highway Dep’t v. Barnwell Bros., 303 U.S. 177 (1938).

- Jump to essay-16Coleman, 307 U.S. at 442–43. The converse is not true, however, and the interest of a state official in vindicating the Constitution provides no legal standing to attack the constitutionality of a state statute in order to avoid compliance with it. Smith v. Indiana, 191 U.S. 138 (1903); Braxton Cnty. Ct. v. West Virginia, 208 U.S. 192 (1908); Marshall v. Dye, 231 U.S. 250 (1913); Stewart v. Kansas City, 239 U.S. 14 (1915). See also Coleman v. Miller, 307 U.S. 433, 437–46 (1939).

- source

- source

- source

- source

- source

- source

Due Process vs Substantive Due Process learn more HERE

Understanding Due Process PDF Explaining how this clause caused over 200 overturns in just DNA alone Click Here

Mathews v. Eldridge – Due Process – 5th & 14th Amendment Mathews Test – 3 Part Test – Amdt5.4.5.4.2 Mathews Test

“Unfriending” Evidence – 5th Amendment

At the Intersection of Technology and Law

Need to learn more click any of the great informational links below

To Learn More…. Read MORE Below and click the links Below

Abuse & Neglect – The Mandated Reporters (Police, D.A & Medical & the Bad Actors)

Mandated Reporter Laws – Nurses, District Attorney’s, and Police should listen up

If You Would Like to Learn More About: The California Mandated Reporting LawClick Here

To Read the Penal Code § 11164-11166 – Child Abuse or Neglect Reporting Act – California Penal Code 11164-11166Article 2.5. (CANRA) Click Here

Mandated Reporter formMandated ReporterFORM SS 8572.pdf – The Child Abuse

ALL POLICE CHIEFS, SHERIFFS AND COUNTY WELFARE DEPARTMENTS INFO BULLETIN:

Click Here Officers and DA’s for (Procedure to Follow)

It Only Takes a Minute to Make a Difference in the Life of a Child learn more below

You can learn more here California Child Abuse and Neglect Reporting Law its a PDF file

Learn More About True Threats Here below….

We also have the The Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) – 1st Amendment

CURRENT TEST = We also have the The ‘Brandenburg test’ for incitement to violence – 1st Amendment

We also have the The Incitement to Imminent Lawless Action Test– 1st Amendment

We also have the True Threats – Virginia v. Black is most comprehensive Supreme Court definition – 1st Amendment

We also have the Watts v. United States – True Threat Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Clear and Present Danger Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Gravity of the Evil Test – 1st Amendment

We also have the Elonis v. United States (2015) – Threats – 1st Amendment

Learn More About What is Obscene…. be careful about education it may enlighten you

We also have the Miller v. California – 3 Prong Obscenity Test (Miller Test) – 1st Amendment

We also have the Obscenity and Pornography – 1st Amendment

Learn More About Police, The Government Officials and You….

$$ Retaliatory Arrests and Prosecution $$

Anti-SLAPP Law in California

Freedom of Assembly – Peaceful Assembly – 1st Amendment Right

Supreme Court sets higher bar for prosecuting threats under First Amendment 2023 SCOTUS

We also have the Brayshaw v. City of Tallahassee – 1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Publius v. Boyer-Vine –1st Amendment – Posting Police Address

We also have the Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, Florida (2018) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Nieves v. Bartlett (2019) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

We also have the Hartman v. Moore (2006) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

We also have the Reichle v. Howards (2012) – 1st Amendment – Retaliatory Police Arrests

Retaliatory Prosecution Claims Against Government Officials – 1st Amendment

Freedom of the Press – Flyers, Newspaper, Leaflets, Peaceful Assembly – 1$t Amendment – Learn More Here

Vermont’s Top Court Weighs: Are KKK Fliers – 1st Amendment Protected Speech

We also have the Insulting letters to politician’s home are constitutionally protected, unless they are ‘true threats’ – Letters to Politicians Homes – 1st Amendment

We also have the First Amendment Encyclopedia very comprehensive – 1st Amendment

Sanctions and Attorney Fee Recovery for Bad Actors

FAM § 3027.1 – Attorney’s Fees and Sanctions For False Child Abuse Allegations – Family Code 3027.1 – Click Here

FAM § 271 – Awarding Attorney Fees– Family Code 271 Family Court Sanction Click Here

Awarding Discovery Based Sanctions in Family Law Cases – Click Here

FAM § 2030 – Bringing Fairness & Fee Recovery – Click Here

Zamos v. Stroud – District Attorney Liable for Bad Faith Action – Click Here

Malicious Use of Vexatious Litigant – Vexatious Litigant Order Reversed

Mi$Conduct – Pro$ecutorial Mi$Conduct Prosecutor$

Attorney Rule$ of Engagement – Government (A.K.A. THE PRO$UCTOR) and Public/Private Attorney

What is a Fiduciary Duty; Breach of Fiduciary Duty

The Attorney’s Sworn Oath

Malicious Prosecution / Prosecutorial Misconduct – Know What it is!

New Supreme Court Ruling – makes it easier to sue police

Possible courses of action Prosecutorial Misconduct

Misconduct by Judges & Prosecutor – Rules of Professional Conduct

Functions and Duties of the Prosecutor – Prosecution Conduct

Standards on Prosecutorial Investigations – Prosecutorial Investigations

Information On Prosecutorial Discretion

Why Judges, District Attorneys or Attorneys Must Sometimes Recuse Themselves

Fighting Discovery Abuse in Litigation – Forensic & Investigative Accounting – Click Here

Criminal Motions § 1:9 – Motion for Recusal of Prosecutor