Supreme Court unanimously reaffirms: There is “NO HATE SPEECH’ exception to the First Amendment

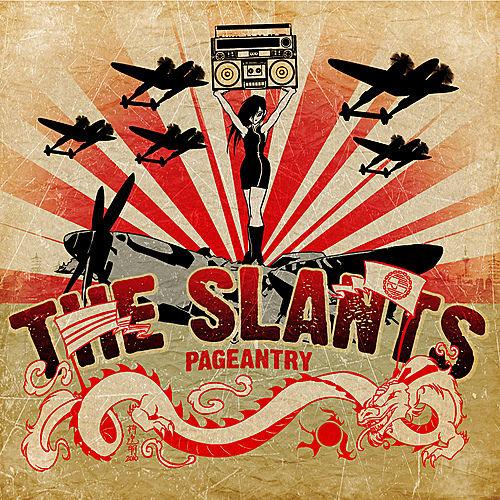

The dispute began when Simon Tam, lead singer of the rock group “The Slants,” sought to register the name of his band. Tam and his bandmates, who are all of Asian descent, chose the name in order to “reclaim” the term and drain its denigrating force as a derogatory term for Asian persons.

today’s opinion by Justice Samuel Alito (for four justices) in Matal v. Tam, the “Slants” case:

[The idea that the government may restrict] speech expressing ideas that offend … strikes at the heart of the First Amendment. Speech that demeans on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, disability, or any other similar ground is hateful; but the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express “the thought that we hate.”

Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote separately, also for four justices, but on this point the opinions agreed:

A law found to discriminate based on viewpoint is an “egregious form of content discrimination,” which is “presumptively unconstitutional.” … A law that can be directed against speech found offensive to some portion of the public can be turned against minority and dissenting views to the detriment of all. The First Amendment does not entrust that power to the government’s benevolence. Instead, our reliance must be on the substantial safeguards of free and open discussion in a democratic society.

And the justices made clear that speech that some view as racially offensive is protected not just against outright prohibition but also against lesser restrictions. In Matal, the government refused to register “The Slants” as a band’s trademark, on the ground that the name might be seen as demeaning to Asian Americans. The government wasn’t trying to forbid the band from using the mark; it was just denying it certain protections that trademarks get against unauthorized use by third parties. But even in this sort of program, the court held, viewpoint discrimination — including against allegedly racially offensive viewpoints — is unconstitutional. And this no-viewpoint-discrimination principle has long been seen as applying to exclusion of speakers from universities, denial of tax exemptions to nonprofits, and much more. source

There Is No Such Thing as ‘Hate Speech’

Yes, that is correct. “Hate speech” is not a category of speech recognized under current constitutional law. It is merely a convenient way to pigeonhole speech that some people find offensive. But what is very troubling is when people begin to treat “hate speech” as unprotected speech. For example, a student leader at Penn State, a university which was recently sued for its unconstitutionally vague and overbroad speech codes, made the following comment featured in a prominent article in the student newspaper The Daily Collegian:

“We support any and all university policies that prohibit intolerant actions against any student on this campus,” said Watson, adding that hate speech was not protected by the constitution. [Emphasis added.]

Unfortunately, this is not the first time that a statement like this has been made. This belief has become somewhat pervasive, especially on college campuses, making it high time to put this fundamentally false and dangerous belief to rest.

There is no constitutional exception for so-called hate speech. The First Amendment fully protects speech that some may find offensive, unpopular, or even racist. The First Amendment allows you to wear a jacket that says “Fuck the Draft” in a public building (see Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15), yell “We’ll take the fucking street later!” during a protest (see Hess v. Indiana, 414 U.S. 105), burn the American flag in protest (Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 and United States v. Eichman, 496 U.S. 310), and even give a racially charged speech to a restless crowd (see Terminello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1). You can even, consistent with the First Amendment, call for the overthrow of the United States government (see Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444). This is not a recent development in constitutional law—these cases date back to 1949.<

The U.S. Supreme Court stated the general rule regarding protected speech quite well in Texas v. Johnson, when it held:

The government may not prohibit the verbal or nonverbal expression of an idea merely because society finds the idea offensive or disagreeable.

Federal courts have consistently followed this holding when applying the First Amendment to public universities. While invalidating sanctions placed on a fraternity for holding an “ugly woman contest,” a federal district court in Iota Xi Chapter of Sigma Chi Fraternity v. George Mason University, 993 F.2d 386, held:

The First Amendment does not recognize exceptions for bigotry, racism, and religious intolerance or ideas or matters some may deem trivial, vulgar or profane.

Furthermore, federal courts have consistently used this concept in striking down college speech codes that regulate offensive or unpopular language (for examples, see Doe v. University of Michigan, 721 F. Supp. 852, UWM Post, Inc., v. Board of Regents of University of Wisc., 774 F. Supp. 1163, and Bair v. Shippensburg Univ., 280 F. Supp. 2d 357). The law is so consistent that not one college speech code challenged in federal court has ever been left standing.

As you can see, it is settled law that public universities, in order to be consistent with the First Amendment, cannot regulate or suppress speech based upon its content, even when it is offensive, vulgar, profane, or unpopular. A university, especially one run with our tax dollars, should be a marketplace of ideas where open and vigorous discourse is encouraged and not suppressed by crafty speech codes and the threat of disciplinary sanctions.

Make sure to check out FIRE’s Guide to Free Speech on Campus for an excellent resource on this subject. source

Matal v. Tam: Supreme Court Invalidates Lanham Act Section Prohibiting “Disparaging” Trademarks

Matal v. Tam, No. 15–1293 (June 19, 2017)

For many years, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(a) prevented the registration of any federal trademark that “may disparage … persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols.” While trademark practitioners and courts have long debated the metes and bounds of this prohibition on “disparaging” marks, the United States Supreme Court just drastically simplified the issue in Matal v. Tam, striking down the prohibition as a violation of the First Amendment.

Factual Summary

In Tam, an Asian-American plaintiff had attempted to obtain a federal trademark on the name of his band “The Slants,” which he chose “in order to ‘reclaim’ the term and drain its denigrating force as a derogatory term for Asian persons.” When the registration was denied based upon § 1052(a), Tam took the matter all the way to the Supreme Court.

The Majority Opinion

In a unanimous opinion, the Supreme Court held that § 1052(a) “offends a bedrock First Amendment principle” — that “[s]peech may not be banned on the ground that it expresses ideas that offend.” Citing the inherent dangers of government picking winners and losers in the marketplace of ideas, the Court pushes back at the idea that trademarks, governing commerce, are meaningfully less expressive than copyrights, and thus any less worthy of being protected against censorship of ideas: “It is true that the necessary brevity of trademarks limits what they can say,” the Court writes. “But powerful messages can sometimes be conveyed in just a few words.” Moreover, “[t]he commercial market is well stocked with merchandise that disparages prominent figures and groups, and the line between commercial and non-commercial speech is not always clear, as this case illustrates.” Thus, the Court warns that, “[i]f affixing the commercial label permits the suppression of any speech that may lead to political or social ‘volatility,’ free speech would be endangered.”

For this same reason, the Court declines to extend a line of precedent concerning “government speech” to categorize the grant of a trademark as the imprimatur of the government itself. “If private speech could be passed off as government speech by simply affixing a government seal of approval, government could silence or muffle the expression of disfavored viewpoints.” Moreover, “if trademarks represent government speech, what does the Government have in mind when it advises Americans to ‘make.believe’ (Sony), ‘Think different’ (Apple), ‘Just do it’ (Nike), or ‘Have it your way’ (Burger King)? Was the Government warning about a coming disaster when it registered the mark ‘EndTime Ministries’?” Framed this way, the Court (in both the majority and concurrence) makes clear that the Trademark Office approving a registration endorses the registrant’s right to source identity in the marketplace and nothing more.

Concurring Opinions

In a concurring opinion joined by half of the Court, Justice Kennedy “explains in greater detail why the First Amendment’s protections against viewpoint discrimination apply to the trademark here” and further contends “that the viewpoint discrimination rationale renders unnecessary any extended treatment of other questions raised by the parties.” Kennedy notes “[i]t is telling that the Court’s precedents have recognized just one narrow situation in which viewpoint discrimination is permissible: where the government itself is speaking or recruiting others to communicate a message on its behalf” or, as a subset of this doctrine, “situations where private speakers are selected for a government program to assist the government in advancing a particular message” — neither of which apply to the issues presented by § 1052(a).

Finally, a one-page concurrence from the ever-cantankerous Justice Thomas notes his personal belief that all attempts by the government to restrict truthful speech warrant strict (rather than intermediate) scrutiny, regardless of whether or not the speech is commercial. While a moot issue for the purposes of the case, since § 1052(a) did not even survive intermediate scrutiny, this is clearly an evergreen point of contention for the Justice.

Conclusion

By invalidating § 1052(a)’s disparagement clause under the First Amendment, the Supreme Court has opened up a wider range of trademarks to be submitted to and accepted by the Trademark Office. While social mores may ultimately curb the use of arguably disparaging marks in the marketplace, Tam has helped ensure that the federal government will no longer play a part in that decision-making process.