The Dark Secret of the MIT Science Club for Children

The class-action lawsuit over the radioactive oatmeal experiment at the Walter E. Fernald State School in Massachusetts in the 1940s and 1950s was settled in 1998 for $1.85 million. The suit claimed that some children were exposed to more radiation than federal limits allowed. The experiment was sponsored by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and Quaker Oats, and involved feeding 73 children oatmeal containing radioactive calcium and other radioisotopes to track how nutrients were digested. The children were tricked into participating in the experiments by joining the Fernald Science Club, and many were wards of the state and inaccurately classified as mentally retarded

On a winter morning in 1994, Massachusetts resident Fred Boyce turned on his car radio, and was shocked by what he heard. A federal committee had just revealed that 50 years earlier, a group of children at Fernald State School—an institution for the developmentally disabled—had been unwittingly fed radioactive cereal by MIT researchers.

“That can’t be right!” he yelled. “That’s me!”

In the late 1940s, Boyce was one of some 90 children, most of whom were classified as “feeble-minded,” selected by MIT to be used as test subjects. With offers of free meals and Boston Red Sox tickets, they’d been coaxed to join a “Science Club” without knowing that their inclusion would make them guinea pigs for various radiation-laden nutrition studies funded by Quaker Oats.

It wasn’t until decades later, on that winter morning in 1994, that Boyce became aware of what he’d been secretly put through. It incited one of history’s most searing debates about the ethics of academic research and the necessity of informed consent.

The “Science Club”

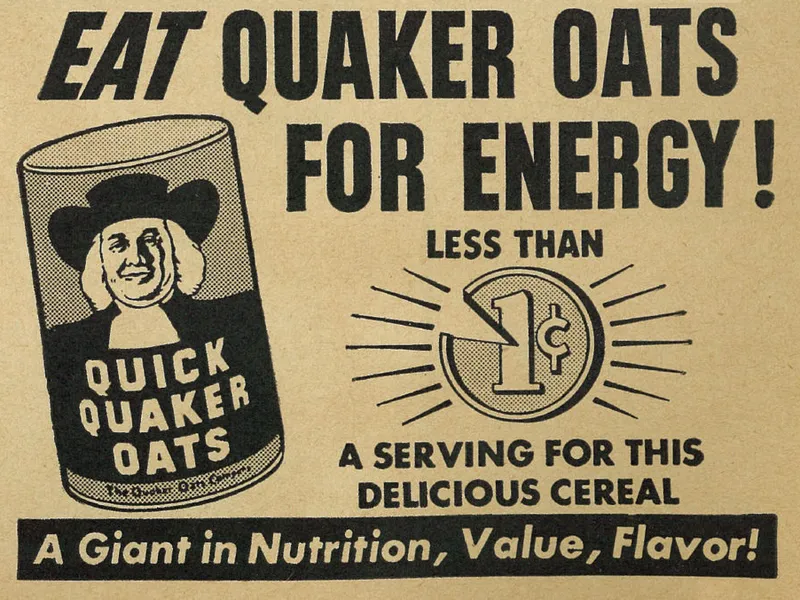

In the late 1940s, two major brands, Quaker Oats and Cream of Wheat, were competing for cereal market share. At the same time, cereals in general were under a bit of nutritional scrutiny: a series of experiments had revealed that plant-based grains contained naturally high levels of phytate, an acid that inhibited the absorption of iron and calcium.

When MIT decided to look into how the human body absorbs essential minerals and vitamins, Quaker jumped at the opportunity to fund the study, largely out of a desire to “give them an advantage over Cream of Wheat.”

After securing additional grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Atomic Energy Commission, MIT formulated a plan: they’d “recruit” 40 children from the Fernald State School, an institution for the developmentally disabled, and feed them cereal with radioactive tracers (which, even today, are used to trace processes in the human body).

Originally dubbed ‘The Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded,” Fernald State School was the first institution in the United States designed for developmentally disabled children. But it was founded on morally dubious principles.

At the turn of the 20th century, Walter E. Fernald became the school’s superintendent. Fernald, who trumpeted the school as a “model in the field of mental retardation,” was a leading proponent of the growing eugenics movement in the United States. The 2,500 children at Fernald were not all developmentally challenged. Some were transferred from shelters, or abandoned their by their parents. But they all were ingrained with the same mentality: that they were not “part of the [human] species.”

For MIT—one of the country’s premier universities—the Fernald Center was the perfect place to conduct research. Subjects were easy to coax into participating, were an ideal control group, and, most importantly, were oblivious to whatever they were being subjected to. When researchers began their Quaker Oats-funded study in 1949, they knew just where to go.

Fernald Center, then named a “School for the Feeble Minded ”(c.1900)

The plan was simple: to feed children copious amounts of Quaker Oats cereal, and track the natural absorption of iron and calcium using radioactive tracers. To recruit test subjects, MIT created a vaguely-titled “Science Club” at Fernald, promising that any child who joined would get “special privileges.”

In a Senate hearing 40 years later, Charles Dyer, who was seven at the time, recalled being coaxed to join the Science Club by MIT researchers. “They gave me a Mickey Mouse watch,” he said, “and they made me feel special.”

Another Science Club member, Austin LaRoque, thirteen at the time, would later describe MIT’s tactics as “misleading:”

“They said [the Club] would benefit us by taking vitamins and stuff. They took us places here and there. [MIT] said they were going to have a Christmas Party for us. And we were young kids. They took advantage of us. We were youngsters. We figured well, we got a chance to get off the grounds for a while, get and and see something—we’ll do it.”

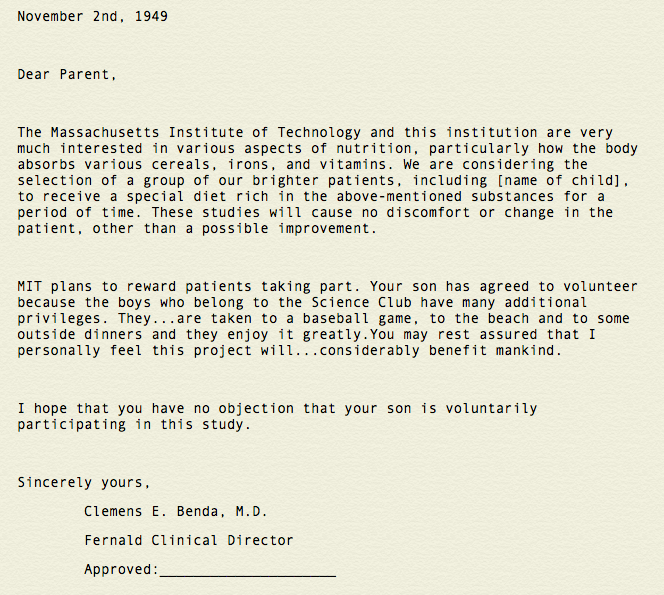

After convincing some 40 youngsters to join the Science Club, MIT then sent out a letter to the children’s parents—many of whom had abandoned them and hadn’t been in touch for years. Rather than mention radioactive exposure or the potential dangers faced by participants, the letter (reproduced below) harped on the benefits Science Club members would receive:

“Some of us had to sign our own forms, but at that particular time I could not read or write,” recalled Austin LaRoque, years later. “I had no knowledge of anything other than the fact that I do what I’m told when I’m told.”

Over the next several weeks, Dyer, along with a few dozen kids between the ages of 7 and 17, were fed “rather large” amounts of Quaker Oats cereal coated with radioactive chemicals, which allowed the researchers to trace the digestion process. The results, which proved that the iron absorption rate of rolled oats was no less than that of farina (Cream of Wheat), “greatly pleased” the Quaker Oats Company.

Some months after the iron experiments, Fernald Science Club members were subjected to a series of tests related to calcium intake. This time, 36 youth each received two breakfasts containing milk (with a radioactive tracer in calcium). The goals was to understand whether or not the phytate chemicals inherent in plant-based cereals “interfered with the dietary uptake of calcium.” Once again, the results were favorable for Quaker: the study found that oatmeal, when combined with milk, provided a sufficient level of calcium.

In a third set of experiments, which sought to understand what happens to calcium in the bloodstream, nine Fernald Science Club youth were injected with syringes full of radioactive calcium. Though obtained immorally, the knowledge acquired from this test eventually laid the foundation for much subsequent research in osteoporosis.

Upon concluding their tests, MIT ended its association with Fernald. Though researchers never followed up with any of the test subjects, they had plenty of time to share their new knowledge with Quaker Oats, whose “high in iron” claims became a vital component of their advertising campaigns.

It would take more than 40 years for the details of the study to be excavated. When that happened, it came with considerable consequences for MIT, Quaker Oats, and everyone else involved.

The Past, Revisited

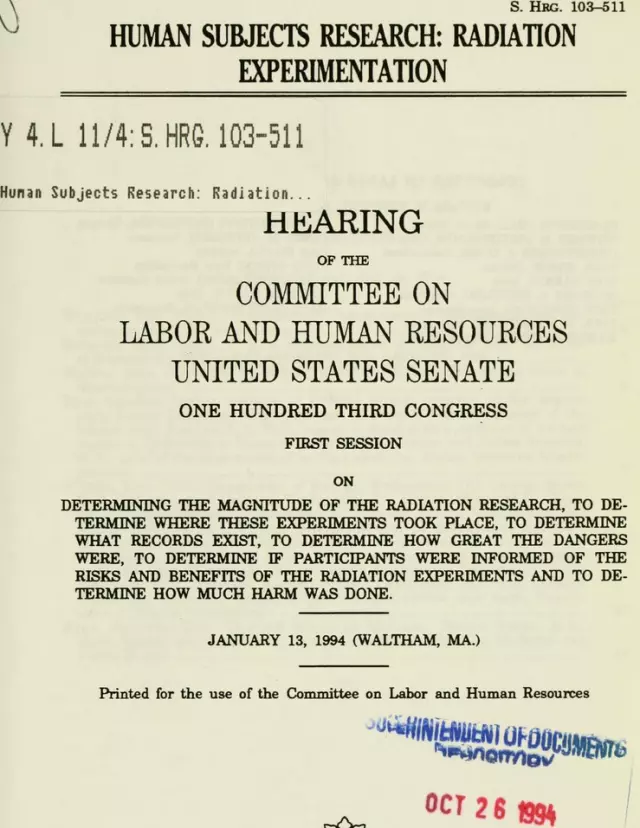

In December of 1993, Scott Allen, a journalist at the Boston Globe, unearthed a trove of papers that documented years of ethically dubious studies conducted on Fernald Center youth. The day after Christmas, he published an article, “Radiation Used on Retarded”, that not only ignited a national debate on the ethics of medical research, but inspired the federal government to launch an investigation into the matter.

What followed was a series of Senate committee hearings on human subjects radiation research. MIT’s Fernald Science Club experiments were right at the center of the scrutiny. The investigators’ immediate concern was identifying just how much radiation the Fernald children had been exposed to.

David Litster, then-Vice President of Research at MIT, faced the daunting task of defending his institution’s shady ethical past. The amount of radioactive exposure, he said, was “minute” and varied based on the subjects’ body weight.

“[For the iron experiment], exposures ranged from 170 millirems to 330 millirems, with an average of 230,” he told the committee. “For the calcium experiments, it was much less, like 12 millirems or less.”

To put these numbers into perspective, 300 millirems is roughly equivalent to receiving 30 consecutive chest x-rays, or one year’s worth of background radiation exposure in a city like Boston—an amount, added Litster, that carried an extra risk of contracting cancer in one of 2,000 cases.

Priceonomics; Data via U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission

IIn experiments of this nature, radioactive tracers were, and still are, commonly used to track chemical reactions within the human body. By itself, the use of them at Fernald was not incredibly controversial.

The more pressing concern was how the experiments were conducted: without informed consent. The letter MIT sent to parents, Representative Joseph P. Kennedy II told the committee, was “deceptive, at best.” Again, MIT defended its actions—this time with some historical background.

At the time of MIT’s study (1949-50), the concept of “informed consent” (or that a human test subject had the right to know exactly what he or she was being subjected to) did not exist. It wasn’t until 1953 that the National Institutes of Health created the first federal policy protecting human subjects; by 1966, the Public Health Service had followed suit, pronouncing that freely given consent was the “cornerstone of ethical experimentation.” The National Research Act of 1974 delineated, for the first time, an across-the-board procedure for conducting ethical research, and it designated that an institution review board (IRB) had to approve research based on informed consent (and a clear description of the risks involved).

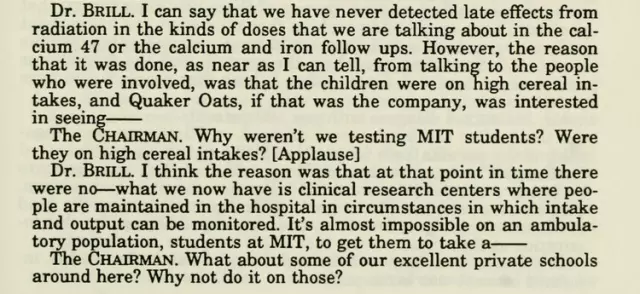

But any work conducted prior to the early 1950s, like MIT’s Fernald Science Club experiments, could be “justified” by the lack of any ethical guidelines. When MIT’s research director, Dr. Bertran Brill, stepped to the podium, he attempted to defend his institution’s choice of using developmentally-challenged children for the study by claiming that they ate more cereal than most people:

Excerpt taken from the Senate Committee hearing Human Subject Research (Radiation Experimentation); January 13, 1994

“I admit they shouldn’t have focused on a population that was so captive and had no alternative,” later ceded Dr. Brill. “That was wrong.”

The Cost of Unethical Research

Shortly after the Senate hearings, legal advertisements were placed in newspapers across the state, imploring previously affected members of the Fernald Science Club, who were by then 60- to 70-years-old, to come forward. In 1997, a group of roughly 30 men, many of whom had mental and physical disabilities, filed a class action lawsuit for $60 million on the grounds that their civil rights had been violated.

The Massachusetts Task Force, which investigated the case, eventually determined that “The letter in which consent from family members was requested…failed to provide information that was reasonably necessary for an informed decision to be made.”

Though MIT maintained that “its researchers acted properly under existing standards of conduct,” they, along with Quaker Oats, agreed to pay out a settlement of $1.85 million to those they’d experimented on decades earlier. According to the original press release, this was merely to “avoid the expense and diversion of a lengthy legal battle.”

“I look on it as the tuition of 20 students,” Vice President of Research, David Litster, told the press. “I got quite a dose of x-rays every time my parents took me to the shoe store—far more than the people got who participated in some of these studies 40 years ago. Does someone owe me an apology, and perhaps a monetary settlement?”

Questions like these sparked a long-standing debate about ethics in research—a debate which saw defensive academics contending against citizens who felt that past research had violated people’s rights. In a 1994 letter to the New York Times, one reader passionately opined the latter stance:

“While this situation may not have been thought to be fraught with medical difficulties, it was contaminated by ethical doubts. Informed consent was cast aside, a slippery slope was put into place, and we all know that leading down that slope was a barbaric chasm.”

“This was about secrecy, an utter disregard for human safety,” agreed a Harvard School of Medicine professor. “All I can say is we can do good research by being honest and fair with people. That’s the only way to do it. If you don’t do it that way, it will backfire.”

Our next post looks at the organization raffling off a swank house amongst the housing scarcity of San Francisco. source

A Spoonful of Sugar Helps the Radioactive Oatmeal Go Down

When MIT and Quaker Oats paired up to conduct experiments on unsuspecting young boys

When Fred Boyce and dozens of other boys joined the Science Club at Fernald State School in 1949, it was more about the perks than the science. Club members scored tickets to Boston Red Sox games, trips off the school grounds, gifts like Mickey Mouse watches and lots of free breakfasts. But Fernald wasn’t an ordinary school, and the free breakfasts from the Science Club weren’t your average bowl of cereal: the boys were being fed Quaker oatmeal laced with radioactive tracers.

The Fernald State School, originally called The Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded, housed mentally disabled children along with those who had been abandoned by their parents. Conditions at the school were often brutal; staff deprived boys of meals, forced them to do manual labor and abused them. Boyce, who lived there after being abandoned by his family, was eager to join the Science Club. He hoped the scientists, in their positions of authority, might see the mistreatment and put an end to it.

“We didn’t know anything at the time,” Boyce said of the experiments. “We just thought we were special.” Learning the truth about the club felt like a deep betrayal.

The boys didn’t find out the whole story about their contaminated cereal for another four decades. During a stretch between the late 1940s and early 1950s, Robert Harris, a professor of nutrition at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, led three different experiments involving 74 Fernald boys, aged 10 to 17. As part of the study, the boys were fed oatmeal and milk laced with radioactive iron and calcium; in another experiment, scientists directly injected the boys with radioactive calcium.

Settlement Reached in Suit Over Radioactive Oatmeal Experiment

A group of former students who ate radioactive oatmeal as unwitting participants in a food experiment will share a $1.85 million settlement from Quaker Oats and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

More than 100 boys at the Fernald School in Waltham, Mass., were fed cereal containing radioactive iron and calcium in the 1940’s and 1950’s. The diet was part of an experiment to prove that the nutrients in Quaker oatmeal travel throughout the body.

Quaker and M.I.T. agreed last week to pay to settle the class-action lawsuit, which covers about 30 people. A hearing is scheduled for April 6 to make the settlement final.

Quaker Oats officials wanted to match the advertising claims of their competitor, Cream of Wheat, which is based on farina, said Alexander Bok, one lawyer for the plaintiffs.

The boys, many of whom were wards of the state and inaccurately classified as mentally retarded, joined the Fernald Science Club in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s.

A $60 million lawsuit was filed in Federal District Court here two years ago asserting that the children were tricked into joining the science club to participate in the experiments. The suit also asserts that some boys were exposed to more radiation than allowed under Federal limits.

M.I.T. said on Tuesday that the exposure to radiation was about equal to the natural background radiation people were exposed to from the environment every year. The university also noted that a state panel in 1994 determined that the students had suffered no significant health effects from the experiment.

The panel did say, however, that the students’ civil rights had been violated.

Quaker Oats continues to deny that it played a large role in the experiments. The company donated the cereal and gave a ”small research grant” to the university, said a Quaker spokesman, Mark Dollins source

Court approves Fernald settlement

The US District Court of Massachusetts has approved a class-action settlement of all claims against MIT and its employees and researchers relating to nutrition studies conducted during the late 1940s and early 1950s at the Fernald School, a state institution in Waltham. Notice of the settlement was published in newspapers across the state during the last week of December.

MIT issued a statement on December 30 that MIT was pleased with the court’s action, which is to be made final in April. The statement went on to say:

“The Fernald School studies were conducted to gain an understanding of how iron and calcium are absorbed in the human digestive systems. The studies used minute amounts (less than one-billionth of an ounce) of radioactive iron and calcium tracers to chart the absorption of calcium and iron in the body from eating oatmeal and farina cereals. The exposures to radiation were approximately equal to the amount of natural background radiation we all receive from the environment each year.

“Both a Commonwealth of Massachusetts and a federal investigation of the studies found no discernible effects on health of the study participants.

“When information regarding these studies was published in early 1994, MIT President Charles M. Vest expressed his concern and regret over the apparent lack of informed consent of the parents of the children at the Fernald School. MIT has had in place for more than two decades numerous safeguards and approval processes that assure informed consent of human subjects of any research.

“MIT believes that its researchers acted properly under then-existing standards and denies any charges of wrongdoing. Nonetheless, MIT has agreed to the settlement in order to avoid the substantial expense and diversion of continued litigation and to bring this matter to a final conclusion.

“Under the terms of the proposed settlement, a fund of $1.85 million will be established for the benefit of the class. It will be funded primarily by MIT and, to a lesser degree, by Quaker Oats Co., which provided a grant to fund the nutrition research,” the statement said.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on January 7, 1998. source

MIT Named in Radiation Suit

Radioactive Material Fed to Children in 1950s Experiments

Radioactive material was fed to more than a dozen children at a state home for the retarded fifty years ago to give Quaker Oats an advantage over Cream of Wheat, according to a $60 million federal suit filed last week.

The suit–brought against the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Quaker Oats and several doctors at the state Fernald School in Waltham–was filed in U.S. District Court Friday on behalf of 15 children used as test subjects as Fernald during the 1940s and 1950s.

Some experiments carried out on the children during the Cold War were for military or medical purposes. But according to Michael Mattchen, the lawyer who filed the suit, much of the research done at Fernald was for the commercial benefit of Quaker Oats.

MIT made the radioactive isotopes and scientists from that school and Harvard carried out the experiments, Mattchen said. The lead researcher, Dr. Clemens E. Benda, was a member of the Harvard Medical School faculty in addition to his post as a researcher at Fernald.

But Mattchen maintained in an interview yesterday with The Crimson that Harvard’s connection to the research was merely tangential. Accordingly, Mattchen said, Harvard University was not named in the suit.

According to the suit, the children were told they were part of a science club to trick them into participating, and some of them were exposed to more radiation than federal limits allowed.

Small amounts of radioactive calcium were put in their cereal, allowing researchers to track the oatmeal as it was digested.

The suit also said the Atomic Energy Commission authorized 3,000 doses of radioactive calcium, but “fewer than 150 doses are accounted for” in public reports, leaving 2,850 does unaccounted for in the records.

“What was the genesis of these particular experiments? It seems simply to be, ‘What are the relative benefits of oatmeal and Cream of Wheat?'” said Mattchen.

“There was an utter failure to treat these kids with any human decency,” he said.

Last year, a state panel said the small amounts of radioactive calcium and iron eaten by 74 residents of the Fernald School had no discernible effect on their health.

But the panel said researchers violated the children’s human rights.

President Clinton apologized last October to members of the “science club” at the Fernald School and to other subjects of radiation experiments sanctioned by the federal government.

His task force said the experiments at the Fernald School were unethical, but the subjects were not hurt and so deserved no federal compensation.

The president of MIT has apologized for the way the Fernald experiments were done.

The suit filed last week asks for $1 million for suffering and $3 million in punitive damages for each test subject “to deter defendants from ever again using human beings … as guinea pigs for experimental procedures.”

This story was compiled using Associated Press wire dispatches. source

RADIOACTIVE OATMEAL SUIT SETTLED FOR $1.85 MILLION

Quaker Oats officials wanted to match the advertising claims of their competitor, farina-based Cream of Wheat, said Alexander Bok, one of the plaintiffs’ 15 lawyers.

“It’s a violation of your civil rights, which is why they’re paying $1.8 million to treat a minor as a guinea pig and to feed them radiation,” Bok said Tuesday.

The boys — many of whom were wards of the state and inaccurately classified as mentally retarded — joined the “Fernald Science Club” in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

A $60 million lawsuit, filed in U.S. District Court two years ago, alleged the children were tricked into joining the science club in order to participate in the experiments. The suit claims some were exposed to more radiation than allowed under federal limits.

“They put out a consent form that neglects to mention that there’s radioactivity {in the oatmeal},” Bok said. “If the radiation was okay, why didn’t they disclose it?”

MIT President Charles Vest apologized for the way the Fernald experiments were conducted when reports about them were first published in 1994.

Quaker Oats continues to deny it played a large role in the Fernald experiments. The company donated the cereal and gave a “small research grant” to MIT, Quaker spokesman Mark Dollins said.

Originally, the lawsuit had eight to 10 plaintiffs. About 20 more came forward as a result of newspaper advertisements last week that invited potential parties to the case to identify themselves.

The state also is sending notices to about 100 others believed to have been subjected to the experiments.

Bok said it is possible some plaintiffs won’t agree to settle, in which case MIT could withdraw from the proposed deal. source

MIT, Quaker Oats Settle Radiation Lawsuit

- To: radsafe@romulus.ehs.uiuc.edu

- Subject: MIT, Quaker Oats Settle Radiation Lawsuit

- From: “Sandy Perle” <sandyfl@ix.netcom.com>

- Date: Fri, 2 Jan 1998 16:53:55 -0800

- Priority: normal

- Reply-to: sandyfl@ix.netcom.com

This is of general interest, and, might raise questions. Therefore, I am providing the entire article as found on the wire services. It was a subject I had not been awarre of, and, this might be new to others as well. Happy New Year to all Radsafers! ================================ BOSTON (Reuters) December 31 10:58 AM EST - The Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Quaker Oats Co. agreed to pay $1.85 million to former students of a Massachusetts school used in radiation experiments without their knowledge 40 to 50 years ago, officials said Wednesday. The prestigious university will pay the bulk of the class-action settlement, approved by the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts Tuesday, for the controversial nutrition studies, MIT officials said. Members of the science club at the Fernald School in Waltham, Mass., were fed, without their knowledge, breakfast cereal and iron supplements contaminated with minute amounts of radiation between 1945 and 1956. Quaker Oats provided a grant to fund the research into how iron and calcium are absorbed by the human digestive system, MIT said. "The exposures to radiation were approximately equal to the amount of natural background radiation we all receive from the environment each year," MIT said in a statement. "Both a Commonwealth of Massachusetts and a federal investigation into of the studies found no discernible effects on health of study participants." At least 90 boys, aged 10 to 16, were used in the experiments, said Jeffrey Petrucelly, an attorney for the former students. They have only found out in the last two or three years about the radiation doses, he said. "MIT and the school informed the parents the children would be involved in a science club learning about nutrition and science in general. In fact, they were experimented on with radioactive isotopes," Petrucelly said. Legal advertisements have been placed in newspapers across the state to contact former classmates of the settlement. MIT said it believes its researchers acted properly under existing standards of conduct. But the school agreed to the settlement to avoid the expense and diversion of a lengthy legal battle. source ------------------ Sandy Perle Technical Director ICN Dosimetry Division Costa Mesa, CA 92626 Office: (800) 548-5100 x2306 Fax: (714) 668-3149 sandyfl@ix.netcom.com sperle@icnpharm.com Personal Homepage: http://www.geocities.com/CapeCanaveral/1205 ICN Dosimetry Website: http://www.dosimetry.com

MIT, Quaker Oats Settle Radiation Lawsuit

- To: “RADSAFE” <RADSAFE@romulus.ehs.uiuc.edu>

- Subject: MIT, Quaker Oats Settle Radiation Lawsuit

- From: “George J. Vargo, Ph.D., CHP” <vargo@physicist.net>

- Date: Fri, 2 Jan 1998 22:51:48 -0800

- Reply-To: “George J. Vargo, Ph.D., CHP” <vargo@physicist.net>

Just in case it wasn't posted previously. --GJV MIT, Quaker Oats Settle Radiation Lawsuit Copyright 1997 by Reuters ** via ClariNet ** / Wed, 31 Dec 1997 8:52:57 PST BOSTON (Reuters) - The Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Quaker Oats Co. agreed to pay $1.85 million to former students of a Massachusetts school used in radiation experiments without their knowledge 40 to 50 years ago, officials said Wednesday. The prestigious university will pay the bulk of the class-action settlement, approved by the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts Tuesday, for the controversial nutrition studies, MIT officials said. Members of the science club at the Fernald School in Waltham, Mass., were fed, without their knowledge, breakfast cereal and iron supplements contaminated with minute amounts of radiation between 1945 and 1956. Quaker Oats provided a grant to fund the research into how iron and calcium are absorbed by the human digestive system, MIT said. ``The exposures to radiation were approximately equal to the amount of natural background radiation we all receive from the environment each year,'' MIT said in a statement. ``Both a Commonwealth of Massachusetts and a federal investigation into of the studies found no discernible effects on health of study participants.'' At least 90 boys, aged 10 to 16, were used in the experiments, said Jeffrey Petrucelly, an attorney for the former students. They have only found out in the last two or three years about the radiation doses, he said. ``MIT and the school informed the parents the children would be involved in a science club learning about nutrition and science in general. In fact, they were experimented on with radioactive isotopes,'' Petrucelly said. Legal advertisements have been placed in newspapers across the state to contact former classmates of the settlement. MIT said it believes its researchers acted properly under existing standards of conduct. But the school agreed to the settlement to avoid the expense and diversion of a lengthy legal battle. source George J. Vargo, Ph.D., CHP 509-375-0984 509-371-9014 (fax) vargo@physicist.net

Did Quaker Oats Fund MIT Research That Fed Radioactive Cereal to Kids?

The experimental subjects, from the Walter E. Fernald State School in Massachusetts, had been deemed “mentally retarded.”

Quaker Oats, MIT, and Harvard conducted or funded research on children deemed “mentally retarded” that involved feeding them radioactive breakfast cereal while telling them they were in a “science club.”

A topic that often emerges as something that sounds too bad to be true involves claims related to Quaker Oats’ funding research that fed radioactive oatmeal to unsuspecting children housed at a state institution. These unwitting subjects, the story goes, were given gifts and trips to baseball games in return for their uninformed consent. They were told they were part of a “science club.”

These details are true. Though the research, conducted in the 1950s, was never secret or hidden, it came to wide public attention in the early 1990s. In late 1993, U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Secretary Hazel O’Leary launched an initiative to highlight past research supported by the DOE involving human subjects and radiation now considered to be highly unethical.

On Dec. 26, 1993, the Boston Globe released a front page investigation into a set of experiments mentioned in that DOE review that had been conducted on subjects from the Walter E. Fernald State School in Massachusetts:

Records at the Fernald State School list them as “morons,” but the researchers from MIT and Harvard University called the retarded teenage boys who took part in their radiation experiments “the Fernald Science Club.”

In the name of science, members of the club would eat cereal mixed with radioactive milk for breakfast or digest a series of iron supplements that gave them the radiation-equivalent of at least 50 chest X-rays.

From 1946 to 1956, scores of retarded teenagers consumed radioactive food to help the researchers better understand the human digestive process.

These experiments sought to see what effect cereal and other breakfast foods had on the absorption of elements like iron and calcium. To achieve the information needed, the nutrients at issue needed to be traced. Radioactive isotopes of iron and calcium, which would be absorbed by the body the same as the non-radioactive kind, could be traced with Geiger counters.

These experiments were run, primarily, by a then-PhD student at MIT named Felix Bronner. He was, during the time some of these experiments were conducted, funded as a “Quaker Oaks Fellow.”

Harvard and MIT have each acknowledged their role in these experiments. In 1994, following the completion of a task force’s report on the research, MIT’s Dean of Research issued this statement decrying the lack of informed consent but concluding that “no harm was done”:

J. David Litster, MIT vice president, dean for research and professor of physics, said in a statement:

“Chairman Fred Misilo, the Rev. Doe West and the entire Task Force on Human Subject Research are to be congratulated for the hard work and thought they have put into completing a difficult mission over the past four months.

“As MIT President Charles M. Vest said in January, MIT has expressed its sorrow that the young people who participated decades ago in the nutritional tracer studies-and their parents-apparently were not informed that the study involved radioactive tracers in very small amounts.

“I am pleased that the Task Force has confirmed MIT’s initial impression that no harm was done to the participants in the cereal nutrition studies that were the initial focus of publicity,” Professor Litster said.

Quaker Oats, along with MIT, settled a class action lawsuit brought by former students involved in the experiments regarding the radiation tests in 1998, but the company has denied it played a large role in the research, as reported by The New York Times in 1998:

Quaker Oats continues to deny that it played a large role in the experiments. The company donated the cereal and gave a ”small research grant” to the university, said a Quaker spokesman, Mark Dollins.

Below, Snopes provides the historical context behind many assertions made about these experiments.

Were the Subjects or Their Parents Not Told About the Radiation?

The Federal Task force looking into the informed consent of these experiments was able to locate copies of some “permission” letters sent to parents about their child’s potential participation in these experiments:

May 1953

Dear Parent:

In previous years we have done some examinations in connection with the nutritional department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with the purposes of helping to improve the nutrition of our children and to help them in general more efficiently than before.

For the checking up of the children, we occasionally need to take some blood samples, which are then analyzed. The blood samples are taken after one test meal which consists of a special breakfast meal containing a certain amount of calcium. We have asked for volunteers to give a sample of blood once a month for three months, and your son has agreed to volunteer because the boys who belong to the Science Club have many additional privileges. They get a quart of milk daily during that time, and are taken to a baseball game, to the beach and to some outside dinners and they enjoy it greatly.

I hope that you have no objection that your son is voluntarily participating in this study. The first study will start on Monday, June 8th, and if you have not expressed any objections we will assume that your son may participate.

Sincerely yours,

Clemens E. Benda, M.D.

[Fernald] Clinical Director

Approved:_____________________

Malcom J. Farrell, M.D.

[Fernald] Superintendent

Clemens Benda was a professor at Harvard Medical School in addition to working at the Fernald School. Notably, these letters show that the parents were presented with an “opt-out” choice, meaning that, in lieu of their explicit disapproval, the school would use their children as they saw fit.

Even more notably, the letter does not mention radiation.

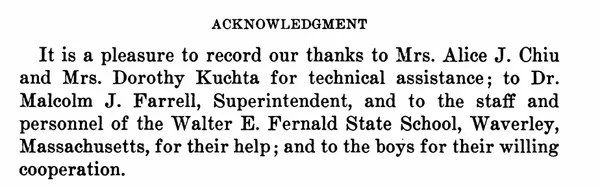

The acknowledgement section of several papers produced from this research misleadingly states that the students were willing participants in the experiments: source